Egg

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly

Most

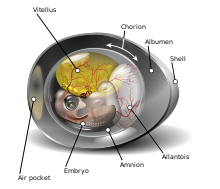

, do not.Reptile eggs, bird eggs, and monotreme eggs are laid out of water and are surrounded by a protective shell, either flexible or inflexible. Eggs laid on land or in nests are usually kept within a warm and favorable temperature range while the embryo grows. When the embryo is adequately developed it hatches, i.e., breaks out of the egg's shell. Some embryos have a temporary egg tooth they use to crack, pip, or break the eggshell or covering.

The largest recorded egg is from a

Reproductive structures similar to the egg in other

Eggs of different animal groups

Several major groups of animals typically have readily distinguishable eggs.

| Class | Types of eggs | Development |

|---|---|---|

| Jawless fish | Mesolecithal eggs, especially large in hagfish[3] | ] |

| Cartilaginous fish | Macrolecithal eggs with egg capsule[3] | Direct development, viviparity in some species[6][page needed] |

| Bony fish | Macrolecithal eggs, small to medium size, large eggs in the coelacanth[7] | Larval stage, ovovivipary in some species.[8] |

| Amphibians | Medium-sized mesolecithal eggs in all species.[7] | Tadpole stage, direct development in some species.[7] |

Reptiles

|

Large macrolecithal eggs, develop independent of water.[9] | Direct development, some ovoviviparious |

Birds

|

Large to very large macrolecithal eggs in all species, develop independent of water.[3] | The young more or less fully developed, no distinct larval stage. |

Mammals

|

Macrolecithal eggs in placental mammals.[3]

|

Young little developed with indistinct larval stage in monotremes and marsupials, direct development in placentals. |

Fish and amphibian eggs

The most common reproductive strategy for fish is known as oviparity, in which the female lays undeveloped eggs that are externally fertilized by a male. Typically large numbers of eggs are laid at one time (an adult female cod can produce 4–6 million eggs in one spawning) and the eggs are then left to develop without parental care. When the larvae hatch from the egg, they often carry the remains of the yolk in a yolk sac which continues to nourish the larvae for a few days as they learn how to swim. Once the yolk is consumed, there is a critical point after which they must learn how to hunt and feed or they will die.

A few fish, notably the

In certain scenarios, some fish such as the

The eggs of fish and

Bird eggs

Bird eggs are laid by females and

Colours

The default colour of vertebrate eggs is the white of the

Non-passerines typically have white eggs, except in some ground-nesting groups such as the

For the same reason, later eggs in a clutch are more spotted than early ones as the female's store of calcium is depleted.

The color of individual eggs is also genetically influenced, and appears to be inherited through the mother only, suggesting that the

It used to be thought that color was applied to the shell immediately before laying, but subsequent research shows that coloration is an integral part of the development of the shell, with the same protein responsible for depositing calcium carbonate, or protoporphyrins when there is a lack of that mineral.

In species such as the

Yolks of birds' eggs are yellow from carotenoids, it is affected by their living conditions and diet.[10]

Shell

Bird eggshells are diverse. For example:

- cormorant eggs are rough and chalky

- tinamou eggs are shiny

- duck eggs are oily and waterproof

- cassowary eggs are heavily pitted

Tiny pores in bird eggshells allow the embryo to breathe. The domestic hen's egg has around 7000 pores.[13]

Some bird eggshells have a coating of

Shape

Most bird eggs have an

Cliff-nesting birds often have highly conical eggs. They are less likely to roll off, tending instead to roll around in a tight circle; this trait is likely to have arisen due to evolution via natural selection. In contrast, many hole-nesting birds have nearly spherical eggs.[17]

Predation

Many animals feed on eggs. For example, principal predators of the

Brood parasitism occurs in birds when one species lays its eggs in the nest of another. In some cases, the host's eggs are removed or eaten by the female, or expelled by her chick. Brood parasites include the cowbirds and many Old World cuckoos.

Various examples

-

An average whooping crane egg is 102 mm (4.0 in) long and weighs 208 g (7.3 oz)

-

Eurasian oystercatcher eggs camouflaged in the nest

-

Egg of a senegal parrot, a bird that nests in tree holes, on a 1 cm (0.39 in) grid

-

Finch egg next to American dime

-

Eggs ofpigeon and blackbird

-

Egg of an emu

-

Egg from a chicken compared to a 1 euro coin, great tit egg and a corn grain

-

A spherical chicken egg

Amniote eggs and embryos

Like amphibians,

Reptile eggs are often rubbery and are always initially white. They are able to survive in the air. Often the sex of the developing embryo is determined by the temperature of the surroundings, with cooler temperatures favouring males. Not all reptiles lay eggs; some are

Dinosaurs laid eggs, some of which have been preserved as petrified fossils.

Among mammals, early extinct species laid eggs, as do

Mammalian eggs

The eggs of the egg-laying mammals (the platypus and the echidnas) are macrolecithal eggs very much like those of reptiles. The eggs of marsupials are likewise macrolecithal, but rather small, and develop inside the body of the female, but do not form a placenta. The young are born at a very early stage, and can be classified as a "larva" in the biological sense.[18]

In

Invertebrate eggs

Eggs are common among

Evolution and structure

All sexually reproducing life, including both plants and animals, produces

A recent proposal suggests that the phylotypic animal body plans originated in cell aggregates before the existence of an egg stage of development. Eggs, in this view, were later evolutionary innovations, selected for their role in ensuring genetic uniformity among the cells of incipient multicellular organisms.[19]

Formation

The cycle of the egg's formation is started by the

Scientific classifications

Scientists often classify animal reproduction according to the degree of development that occurs before the new individuals are expelled from the adult body, and by the yolk which the egg provides to nourish the embryo.

Egg size and yolk

Microlecithal

Small eggs with little yolk are called microlecithal. The yolk is evenly distributed, so the cleavage of the egg cell cuts through and divides the egg into cells of fairly similar sizes. In

Microlecithal eggs require minimal yolk mass. Such eggs are found in

In placental mammals, where the embryo is nourished by the mother throughout the whole fetal period, the egg is reduced in size to essentially a naked egg cell.

Mesolecithal

Mesolecithal eggs have comparatively more yolk than the microlecithal eggs. The yolk is concentrated in one part of the egg (the vegetal pole), with the cell nucleus and most of the cytoplasm in the other (the animal pole). The cell cleavage is uneven, and mainly concentrated in the cytoplasma-rich animal pole.[3]

The larger yolk content of the mesolecithal eggs allows for a longer fetal development. Comparatively anatomically simple animals will be able to go through the full development and leave the egg in a form reminiscent of the adult animal. This is the situation found in hagfish and some snails.[4][21] Animals with smaller size eggs or more advanced anatomy will still have a distinct larval stage, though the larva will be basically similar to the adult animal, as in lampreys, coelacanth and the salamanders.[3]

Macrolecithal

Eggs with a large yolk are called macrolecithal. The eggs are usually few in number, and the embryos have enough food to go through full fetal development in most groups.[7] Macrolecithal eggs are only found in selected representatives of two groups: Cephalopods and vertebrates.[7][22]

Macrolecithal eggs go through a different type of development than other eggs. Due to the large size of the yolk, the cell division can not split up the yolk mass. The fetus instead develops as a plate-like structure on top of the yolk mass, and only envelopes it at a later stage.

In addition to bony fish and cephalopods, macrolecithal eggs are found in cartilaginous fish, reptiles, birds and monotreme mammals.[3] The eggs of the coelacanths can reach a size of 9 cm (3.5 in) in diameter, and the young go through full development while in the uterus, living on the copious yolk.[23]

Egg-laying reproduction

Animals are commonly classified by their manner of reproduction, at the most general level distinguishing egg-laying (Latin. oviparous) from live-bearing (Latin. viviparous).

These classifications are divided into more detail according to the development that occurs before the offspring are expelled from the adult's body. Traditionally:[24]

- Ovuliparity means the female anurans, echinoderms, bivalves and cnidarians. Most aquatic organisms are ovuliparous. The term is derived from the diminutive meaning "little egg".

- Oviparity is where fertilisation occurs internally and so the eggs laid by the female are zygotes (or newly developing embryos), often with important outer tissues added (for example, in a chicken egg, no part outside of the yolk originates with the zygote). Oviparity is typical of birds, reptiles, some cartilaginous fish and most arthropods. Terrestrial organisms are typically oviparous, with egg-casings that resist evaporation of moisture.

- Ovo-viviparity is where the zygote is retained in the adult's body but there are no trophic (feeding) interactions. That is, the embryo still obtains all of its nutrients from inside the egg. Most live-bearing fish, amphibians or reptiles are actually ovoviviparous. Examples include the reptile Anguis fragilis, the sea horse (where zygotes are retained in the male's ventral "marsupium"), and the frogs Rhinoderma darwinii (where the eggs develop in the vocal sac) and Rheobatrachus (where the eggs develop in the stomach).

- Histotrophic viviparity means embryos develop in the female's Marsupials excrete a "uterine milk" supplementing the nourishment from the yolk sac.[25]

- Hemotrophic viviparity is where nutrients are provided from the female's blood through a designated organ. This most commonly occurs through a placenta, found in most mammals. Similar structures are found in some sharks and in the lizard Pseudomoia pagenstecheri.[26][27] In some hylid frogs, the embryo is fed by the mother through specialized gills.[28]

The term hemotropic derives from the Latin for blood-feeding, contrasted with histotrophic for tissue-feeding.[29]

Human use

Food

Eggs laid by many different species, including birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, have probably been eaten by people for millennia. Popular choices for egg consumption are chicken, duck, roe, and caviar, but by a wide margin the egg most often humanly consumed is the chicken egg, typically unfertilized.

Eggs and Kashrut

According to the

Vaccine manufacture

Many vaccines for infectious diseases are produced in fertile chicken eggs. The basis of this technology was the discovery in 1931 by

Culture

Eggs are an important symbol in folklore and mythology, often representing life and rebirth, healing and protection, and sometimes featuring in creation myths.

Although a food item, raw eggs are sometimes thrown at houses, cars, or people. This act, known commonly as "egging" in the various English-speaking countries, is a minor form of vandalism and, therefore, usually a criminal offense and is capable of damaging property (egg whites can degrade certain types of vehicle paint) as well as potentially causing serious eye injury. On Halloween, for example, trick or treaters have been known to throw eggs (and sometimes flour) at property or people from whom they received nothing.[citation needed] Eggs are also often thrown in protests, as they are inexpensive and nonlethal, yet very messy when broken.[34]

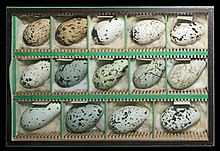

Collecting

Egg collecting was a popular hobby in some cultures, including European Australians. Traditionally, the embryo would be removed before a collector stored the egg shell.[35]

Collecting eggs of wild birds is now banned by many jurisdictions, as the practice can threaten rare species. In the United Kingdom, the practice is prohibited by the Protection of Birds Act 1954 and Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.[36] On the other hand, ongoing underground trading is becoming a serious issue.[37]

Since the protection of wild bird eggs was regulated, early collections have come to the museums as curiosities. For example, the Australian Museum hosts a collection of about 20,000 registered clutches of eggs,[38] and the collection in Western Australia Museum has been archived in a gallery.[39] Scientists regard egg collections as a good natural-history data, as the details recorded in the collectors' notes have helped them to understand birds' nesting behaviors.[40]

Gallery

-

Insect eggs, in this case those of the emperor gum moth, are often laid on the underside of leaves.

-

Fish eggs, such as these herring eggs are often transparent and fertilized after laying.

-

mermaid's purse.

-

ATestudo hermanniemerging fully developed from a reptilian egg.

-

A Schistosoma mekongi egg.

-

Eggs of Huffmanela hamo, a nematode parasite in a fish

See also

- List of egg topics

- Animal shell

- Butterfly eggs

- Egg white

- Fossil egg

- Haugh unit

- Oology

- Oval

- Ovary

- Ovulation

- Oviparous

- Trophic egg

References

- ^ "Whale Shark – Cartilaginous Fish". SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-7141-933-3. Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hildebrand, M. & Gonslow, G. (2001): Analysis of Vertebrate Structure. 5th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York City

- ^ S2CID 198158310.

- ISBN 0-12-324801-9.

- OCLC 156157504.

- ^ a b c d e f g Romer, A. S. & Parsons, T. S. (1985): The Vertebrate Body. (6th ed.) Saunders, Philadelphia.

- ISBN 1-56465-193-2.

- ^ a b Stewart J. R. (1997): Morphology and evolution of the egg of oviparous amniotes. In: S. Sumida and K. Martin (ed.) Amniote Origins-Completing the Transition to Land (1): 291–326. London: Academic Press.

- ^ a b Rääbus, Carol (18 February 2018). "The chemistry of eggshell colours". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Solomon, S.E. (1987). "Egg shell pigmentation". In Wells, R.G.; Belyarin, C.G. (eds.). Egg Quality: Current Problems and Recent Advances. London: Butterworths. pp. 147–157.

- .

- ^ "The Parts of the Egg". www.sites.ext.vt.edu. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016.

- .

- S2CID 11962022.

- ^ Yong, Ed (22 June 2017). "Why Are Bird Eggs Egg-Shaped? An Eggsplainer". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Yutaka Nishiyama (2012). "The Mathematics of Egg Shape" (PDF). International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics. 78 (5): 679–689.

- ISBN 0-471-85074-8

- PMID 21557469.

- PMID 21672788.

- ^ a b Barns, R.D. (1968): Invertebrate Zoology. W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia. 743 pages

- ^ Nixon, M. & Messenger, J.B (eds) (1977): The Biology of Cephalopods. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London, pp 38–615

- ^ Fricke, H.W. & Frahm, J. (1992): Evidence for lecithotrophic viviparity in the living coelacanth. Naturwissenschaften no 79: pp. 476–479

- ^ Thierry Lodé 2001. Les stratégies de reproduction des animaux (reproduction strategies in animal kingdom). Eds Dunod Sciences, Paris

- ISBN 978-0123948151. Archived from the original on 1 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2014.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- S2CID 782433.

- ISBN 978-0125449014.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine Kashrut: Jewish Dietary Laws

- ^ Hall, Stephanie (2017-04-06). "The Ancient Art of Decorating Eggs | Folklife Today". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ Barooah, Jahnabi (2012-04-02). "Easter Eggs: History, Origin, Symbolism And Traditions (PHOTOS)". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ L'ou com balla Archived 2016-04-09 at the Wayback Machine, Barcelona Cathedral.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Chitra (2015-10-05). "Beyond a yolk: a brief history of egging as a political protest". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Collecting bird eggs". echonewspaper.com.au. 2017-03-09. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Protection of Birds Act 1954". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ Wheeler, Timothy (2015-03-16), Poached, retrieved 2018-03-31

- ^ "Egg specimens – Australian Museum". australianmuseum.net.au. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Explore our Egg Collection | Western Australian Museum". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ Golembiewski, Kate. "The Lost Victorian Art of Egg Collecting". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-03-31.