French Constitution of 1791

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

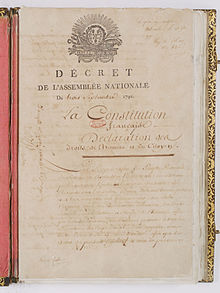

| French Constitution of 1791 | |

|---|---|

French Constitution of 1791. | |

| Original title | (in French) Constitution française du 3 septembre 1791 |

The French Constitution of 1791 (

Drafting process

Early efforts

Following the Tennis Court Oath, the National Assembly began the process of drafting a constitution as its primary objective. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted on 26 August 1789 eventually became the preamble of the constitution adopted on 3 September 1791.[1] The Declaration offered sweeping generalizations about rights, liberty, and sovereignty.[2]

A twelve-member Constitutional Committee was convened on 14 July 1789 (coincidentally the day of the

Many proposals for redefining the French state were floated, particularly in the days after the remarkable sessions of

The main controversies early on surrounded the issues of what level of power to be granted to the

New Constitutional Committee

A second Constitutional Committee quickly replaced it, and included Talleyrand, Abbé Sieyès, and Le Chapelier from the original group, as well as new members Gui-Jean-Baptiste Target, Jacques Guillaume Thouret, Jean-Nicolas Démeunier, François Denis Tronchet, and Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne, all of the Third Estate. As Simon Schama has pointed out, many of the members of the Constitutional Committee were themselves members of nobility, many of whom would later face execution.[3]

Their greatest controversy faced by this new committee surrounded the issue of

Committee of Revisions

A second body, the Committee of Revisions, was struck September 1790, and included

Results

After very long negotiations, the constitution was reluctantly accepted by King

Evaluation

The Assembly, as constitution-framers, were afraid that if only representatives governed France, it was likely to be ruled by the representatives' self-interest; therefore, the king was allowed a suspensive veto to balance out the interests of the people. By the same token, representative democracy weakened the king’s executive authority.

The constitution was not egalitarian by today's standards. It distinguished between the propertied active citizens and the poorer passive citizens. Women lacked rights to liberties such as education, freedom to speak, write, print and worship.[citation needed]

Keith M. Baker writes in his essay “Constitution” that the National Assembly threaded between two options when drafting the Constitution: they could modify the existing, unwritten constitution centered on the three

With the

Timeline of French constitutions

See also

- De Tracy's longest speech to the Constituent Assembly was on the situation in Saint-Domingue, which was repeatedly interrupted by applause and published in a separate pamphlet.[5]

- French Revolution

- Kingdom of France (1791–92)

- United States Constitution

- Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth 1791 Constitution

References

- ^ The Constitution of 1791

- ISBN 978-0-393-93888-3.

- ^ Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, NY: Penguin Books p. 478 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Pertue, M. "Constitution de 1791," in Soboul, Ed., "Dictionnaire historique de la Revolution francaise," pp. 282–283. Quadrige/PUF, Paris: 2005. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Opinion de M. de Tracy sur les affaires de Saint-Domingue, en septembre 1791. Paris: Laillet, s. a. (1791)

External links

- "Constitution de 1791". Conseil constitutionnel (in French). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Constitution of 1791, University of California, Santa Cruz (in English) (partial only)

- Constitution of 1791: complete text Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine