History of agriculture

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

|

| Rural area |

|---|

Wild

In

In South America, agriculture began as early as 9000 BC, starting with the cultivation of several species of plants that later became only minor crops. In the

The

Origins

Origin hypotheses

Scholars have developed a number of hypotheses to explain the historical origins of agriculture. Studies of the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies indicate an antecedent period of intensification and increasing sedentism; examples are the Natufian culture in the Levant and the Early Chinese Neolithic in China. Current models indicate that wild stands that had been harvested previously started to be planted, but were not immediately domesticated.[27][28]

Localised climate change is the favoured explanation for the origins of agriculture in the Levant.[1] When major climate change took place after the last ice age (c. 11,000 BC), much of the earth became subject to long dry seasons.[29] These conditions favoured annual plants which die off in the long dry season, leaving a dormant seed or tuber. An abundance of readily storable wild grains and pulses enabled hunter-gatherers in some areas to form the first settled villages at this time.[1] Across Western Eurasia it was not until approximately 4,000 BC that farming societies completely replaced hunter-gatherers. These technologically advanced societies expanded faster in areas with less forest, pushing hunter-gatherers into denser woodlands. Only the middle-late Bronze Age and Iron Age societies were able to fully replace hunter-gatherers in their final stronghold located in the most densely forested areas. Unlike their Bronze and Iron Age counterparts, Neolithic societies couldn't establish themselves in dense forests, and Copper Age societies had only limited success. [30]

Early development

Early people began altering communities of

WildAgriculture began independently in different parts of the globe and included a diverse range of taxa. At least 11 separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent

It was not until after 9500 BC that the eight so-called

Domesticated

By 8000 BC, farming was entrenched on the banks of the

Agriculture was independently developed on the island of New Guinea.[50] Banana cultivation of Musa acuminata, including hybridization, dates back to 5000 BC, and possibly to 8000 BC, in Papua New Guinea.[51][52]

In northern

In southern China, rice was domesticated in the

In the

Civilizations

Sumer

Ancient Egypt

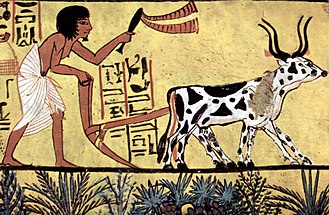

The civilization of

Indian Subcontinent

Ancient China

Records from the

For agricultural purposes, the Chinese had innovated the

Asian rice was domesticated 8,200–13,500 years ago in China, with a single genetic origin from the wild rice

Ancient Greece and Hellenistic world

The major cereal crops of the

Roman Empire

In the

The Americas

Agricultural history took a different path from the Old World as the Americas lacked large-seeded, easily domesticated grains (such as wheat and barley) and large domestic animals that could be used for agricultural labor. Rather than the practice which developed in the Old World of sowing a field with a single crop, pre-historic American agriculture usually consisted of cultivating many crops close to each other utilizing only hand labor. Moreover, agricultural areas in the Americas lacked the uniformity of the east–west area of Mediterranean and semi-arid climates in southern Europe and southwestern Asia, but instead had a north–south pattern with a variety of different climatic zones in close proximity to each other. This fostered the domestication of many different plants.[102]

At the time of first contact between the Europeans and the Americans, the Europeans practiced "extensive agriculture, based on the plough and draught animals," with tenants under landlords, but also forced labor or slavery, while the Indigenous peoples of the Americas practiced "intensive agriculture, based on human labour."[103] Europeans wanted control of land for the grazing of their livestock and property rights for the control of production. Though they were impressed with the productivity of traditional farming techniques, they saw no connection to their system and were dismissive of Native American practices as "gardening" rather than a commercializable enterprise.[103][104] Due to several thousand years of selective breeding, maize, the hemisphere's most important crop, was more productive than Old World grain crops. Maize produced two and one-half times more calories per acre than wheat and barley.[105]

South America

The earliest known areas of possible agriculture in the Americas dating to about 9000 BC are in

In the Andes region, with civilizations including the

The most important crop domesticated in the

Mesoamerica

In Mesoamerica, wild

In

North America

The indigenous people of the

The

A system of

Sub-Saharan Africa

In the Sahel region, civilizations such as the Mali and Songhai empires cultivated sorghum and pearl millet, which were domesticated between 3000 and 2500 BC.[69][70] The donkey was domesticated in Nubia at approximately 5000 BC.[136][137] Archaeological evidence suggests that Sanga cattle may have been independently domesticated in East Africa at around 1600 BC.[138]

In the tropical region of West Africa, crops such as black-eyed peas, Sea Island red peas, yams, kola nuts, Jollof rice and kokoro were domesticated between 3000 and 1000 BC.[71] The coastal region of West Africa is often referred to as the "Yam Belt", due to its high production of yams.[139] The guineafowl is a poultry bird that was domesticated in West Africa, and while the time of the guineafowl's domestication remains unclear, there is evidence that it was present in Ancient Greece during the 5th century BC.[140]

Several species of coffee were also domesticated throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, with Coffea arabica originating in Ethiopia and serving as the main production of modern-day coffee since the late 15th century.[141]

Oceania

Australia

In two regions of Central Australia, the central west coast and eastern central Australia, forms of agriculture were practiced. People living in permanent settlements of over 200 residents sowed or planted on a large scale and stored the harvested food. The Nhanda and Amangu of the central west coast grew yams (Dioscorea hastifolia), while various groups in eastern central Australia (the Corners Region) planted and harvested bush onions (yaua – Cyperus bulbosus), native millet (cooly, tindil – Panicum decompositum) and a sporocarp, ngardu (Marsilea drummondii).[31]: 281–304 [28]

Indigenous Australians used systematic burning, fire-stick farming, to enhance natural productivity.[143] In the 1970s and 1980s archaeological research in south west Victoria established that the Gunditjmara and other groups had developed sophisticated eel farming and fish trapping systems over a period of nearly 5,000 years.[144] The archaeologist Harry Lourandos suggested in the 1980s that there was evidence of 'intensification' in progress across Australia,[145] a process that appeared to have continued through the preceding 5,000 years. These concepts led the historian Bill Gammage to argue that in effect the whole continent was a managed landscape.[31]

Torres Strait Islanders are now known to have planted bananas.[25]

Pacific Islands

In New Guinea, archaeological evidence suggests that agriculture independently emerged around 7,000 years ago with the domestication of crops such as bananas and taro. Pigs and chickens were imported to New Guinea, which were later innovated by other Pacific Island nations, such as those in Polynesia.[146]

Middle Ages and Early Modern period

Europe

The

By AD 900, developments in

Watermills were introduced by the Romans, but were improved throughout the Middle Ages, along with windmills, and used to grind grains into flour, to cut wood and to process flax and wool.[153]

Crops included wheat,

Arab world

From the 8th century to the 14th century, the

Columbian exchange

After 1492, a

Maize and cassava were introduced from Brazil into Africa by Portuguese traders in the 16th century,

Modern agriculture

British agricultural revolution

Between the 17th century and the mid-19th century, Britain saw a large increase in agricultural productivity and net output. New agricultural practices like

Advice on more productive techniques for farming began to appear in England in the mid-17th century, from writers such as Samuel Hartlib, Walter Blith and others.[168] The main problem in sustaining agriculture in one place for a long time was the depletion of nutrients, most importantly nitrogen levels, in the soil. To allow the soil to regenerate, productive land was often let fallow and, in some places, crop rotation was used. The Dutch four-field rotation system was popularised by the British agriculturist Charles Townshend in the 18th century. The system (wheat, turnips, barley and clover) opened up a fodder crop and grazing crop allowing livestock to be bred year-round. The use of clover was especially important as the legume roots replenished soil nitrates.[169] The mechanisation and rationalisation of agriculture was another important factor.

20th century

Dan Albone constructed the first commercially successful gasoline-powered general-purpose tractor in 1901, and the 1923 International Harvester Farmall tractor marked a major point in the replacement of draft animals (particularly horses) with machines. Since that time, self-propelled mechanical harvesters (combines), planters, transplanters and other equipment have been developed, further revolutionizing agriculture.[175] These inventions allowed farming tasks to be done with a speed and on a scale previously impossible, leading modern farms to output much greater volumes of high-quality produce per land unit.[176]

The

In the past century agriculture has been characterized by increased productivity, the substitution of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides for labour,

The number of people involved in farming in industrial countries fell radically from 24 percent of the American population to 1.5 percent in 2002. The number of farms also decreased, and their ownership became more concentrated; for example, between 1967 and 2002, one million pig farms in America consolidated into 114,000, with 80 percent of the production on factory farms.[186] According to the Worldwatch Institute, 74 percent of the world's poultry, 43 percent of beef, and 68 percent of eggs are produced this way.[186][187]

Famines however continued to sweep the globe through the 20th century. Through the effects of climatic events, government policy, war and crop failure, millions of people died in each of at least ten famines between the 1920s and the 1990s.[188]

Green Revolution

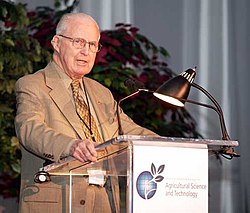

The Green Revolution was a series of research, development, and technology transfer initiatives between the 1940s and the late 1970s. It increased agriculture production around the world, especially from the late 1960s. The initiatives, led by Norman Borlaug and credited with saving over a billion people from starvation, involved the development of high-yielding varieties of cereal grains, expansion of irrigation infrastructure, modernization of management techniques, distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides to farmers.[189]

Synthetic nitrogen, mined

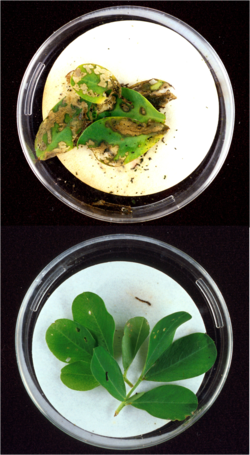

Although the Green Revolution significantly increased rice yields in Asia, yield leveled off. The genetic "yield potential" has increased for wheat, but the yield potential for rice has not increased since 1966, and the yield potential for maize has "barely increased in 35 years". It takes only a decade or two for

Organic agriculture

For most of its history, agriculture has been

See also

References

- ^ a b c "The Development of Agriculture". National Geographic. 2022-07-08. Archived from the original on 2023-01-30. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ S2CID 44865552.

- PMID 26200895.

- S2CID 8202907.

- ^ Hirst, Kris (June 2019). "Domestication History of Rye". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- PMID 37163473.

- ^ PMID 21536870.

- ^ PMID 30845217.

- ^ S2CID 51600014.

- PMID 30880862.

- ISSN 0305-4403.

- PMID 31114806.

- S2CID 220516241.

- ISBN 978-0-521-38456-8, retrieved 2022-08-09

- ^ "Finger Millet". Crop Wild Relatives. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Plant studies show where Africa's early farmers tamed some of the continent's key crops". science.org. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Why It's Difficult to Chart Banana History". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ "Early Africans Went Bananas". science.org. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- PMID 34009300.

- PMID 30622640.

- PMID 26104394.

- ^ World Cotton Production, Yara North America

- ^ National Heritage Places – Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape". Australian Government. Dept of the Environment and Energy. 20 July 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2020. See also attached documents: National Heritage List Location and Boundary Map, and Government Gazette, 20 July 2004.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3.

- ^ a b c "Indigenous Australians 'farmed bananas 2,000 years ago'". BBC News. 12 August 2020.

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (February 2013). "Classical gas". Smithsonian. 43 (10): 18. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Hillman, G.C. (1996) "Late Pleistocene changes in wild plant-foods available to hunter-gatherers of the northern Fertile Crescent: Possible preludes to cereal cultivation". In D.R. Harris (ed.) The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, UCL Books, London, pp. 159–203; Sato, Y. (2003) "Origin of rice cultivation in the Yangtze River basin". In Y. Yasuda (ed.) The Origins of Pottery and Agriculture, Roli Books, New Delhi, p. 196

- ^ a b Gerritsen, R. (2008). Australia and the Origins of Agriculture. Archaeopress. pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Climate". National Climate Data Center. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^

Gavashelishvili, A; et al. (2023), "The time and place of origin of South Caucasian languages: insights into past human societies, ecosystems and human population genetics", Scientific Reports, 13 (21133): 21133, PMID 38036582

- ^ ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-0958-2.

- ISBN 978-92-5-102898-8.

- PMID 18768818.

- PMID 24757054.

- S2CID 39923483.

- PMID 17855556.

- ISBN 978-0-8134-2464-4.

- PMID 23530234.

- S2CID 44282748.

- ISBN 978-0-412-82210-0.

- S2CID 42150441.

- PMID 17170278.

- S2CID 85225244.(subscription required)

- ISBN 978-0-19-954906-1– via Google Books.

- S2CID 84930632.

- S2CID 129087203.

- PMID 19307570.

- ISBN 978-1-57003-000-0.

- S2CID 10644185.

- ^ Nelson, S.C.; Ploetz, R.C.; Kepler, A.K. (2006). "Musa species (bananas and plantains)" (PDF). In Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Hōlualoa, Hawaiʻi: Permanent Agriculture Resources.

- S2CID 10644185.

- S2CID 205246432.

- ^ "Southern Europe, 8000–2000 B.C. Timeline of Art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 26 January 2007. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ "Ceide Fields Visitor Centre, Ballycastle, County Mayo, West of Ireland". Museums of Mayo. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "The Céide Fields and North West Mayo Boglands". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on Oct 17, 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press.

- ^ "Cannabis: Marijuana, hemp and its cultural history". Non-Smokers' Rights Canada. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 9 February 2025. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ S2CID 133660098.

- PMID 19383791.

- ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^ S2CID 44675525.

- .

- S2CID 55719842.

- ^ Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2007–2008). "The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: a synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond". eJournal of Indian Medicine. 1: 87–140.

- ISBN 978-0-415-10054-0.

- S2CID 55763047.

- ISBN 978-1-86320-470-5.

- ^ S2CID 149402650.

- ^ – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-94953-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84593-913-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-955995-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-969726-7.

- ^ "Farming". British Museum. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Tannahill, Reay (1968). The fine art of food. Folio Society.

- ^ .

- )

- ISBN 0-8173-5349-6.

- ^ a b Gupta, Anil K (10 July 2004). "Origin of agriculture and domestication of plants and animals linked to early Holocene climate amelioration". Current Science. 87 (1). Indian Academy of Sciences: 58–59.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-2919-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3.

- ISBN 978-0-521-57652-9.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (1996). Mehrgarh in Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press.

- ISBN 0-631-20546-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-901502-57-2.

- .

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Part 2. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 56.

- ^ Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 57.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. p. 184

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 89, 110.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 33.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 110.

- ^ Robert Greenberger, The Technology of Ancient China, Rosen Publishing Group, 2006, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Wang Zhongshu, trans. by K.C. Chang and Collaborators, Han Civilization (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982).

- ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7.

- PMID 23034647.

- ISBN 3-11-014693-2, pp. 76–77.

- ISBN 3-11-014693-2, p. 77.

- ^ White, K. D. (1970), Roman Farming (Cornell University Press)

- ISBN 0-393-31755-2.

- ^ JSTOR 156945.

- ^ Hill, Christina Gish (24 November 2020). "Returning Corn, Beans, and Squash to Native American Farms". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Ensminger, Marion Eugene; Ensminger, Audrey H. (1994). Food & Nutrition Encyclopedia. London: CRC-Press. p. 1104.

- PMID 18362336.

- S2CID 83061925.

- PMID 24757054.

- PMID 16203994.

- ISBN 978-0-309-04264-2– via nap.edu.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-426-4.

- ISBN 978-3-319-27096-8. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-87451-649-4.

- ISBN 978-92-5-105762-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-5310-2.

- S2CID 161372308.

- ^ Bird, Junius (1946). "The Alacaluf". In Steward, Julian H. (ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. Bulletin 143. Vol. I. –Bureau of American Ethnology. pp. 55–79.

- S2CID 6759459. Archived from the originalon 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ^ Johannessen, S.; Hastorf, C.A. (eds.). Corn and Culture in the Prehistoric New World. Westview Press.

- PMID 20133614.

- .

- OCLC 8561599813. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link - S2CID 144433864.

- ^ Prehistoric Food Production in North America, edited by Richard I. Ford. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Anthropological Papers 75.

- ^ Adair, Mary J. (1988) Prehistoric Agriculture in the Central Plains. Publications in Anthropology 16. University of Kansas, Lawrence.

- ISBN 978-0-19-973496-2.

- ^ Hardigan, Michael A. "P0653: Domestication History of Strawberry: Population Bottlenecks and Restructuring of Genetic Diversity through Time". Pland & Animal Genome Conference XXVI January 13–17, 2018 San Diego, California. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "Pecans at Texas A&M University". Pecankernel.tamu.edu. 2006-08-18. Archived from the original on 2010-05-25. Retrieved 2010-06-03.

- ^ The History of Concord Grapes, http://www.concordgrape.org/bodyhistory.html

- ISBN 978-0-520-24605-8.

- ISBN 978-0-87919-126-9.

- ISBN 978-1-59714-136-9.

- ISBN 978-0-520-24851-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4099-4233-7. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.)

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help - ^ Landon, Amanda J. (2008). "The "How" of the Three Sisters: The Origins of Agriculture in Mesoamerica and the Human Niche". Nebraska Anthropologist. University of Nebraska-Lincoln: 110–124.

- S2CID 12783335.

- ^ Roger Blench, "The history and spread of donkeys in Africa" (PDF). (235 KB)

- S2CID 162307756.

- ^ "Celebrating Nigeria's yummy yams". BBC News. 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ISBN 978-1-84142-018-9.

- ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9.

- ^ Dark Emu

- ^ Jones, R. (1969). "Fire-stick Farming". Australian Natural History. 16: 224.

- ^ Williams, E. (1988) Complex Hunter-Gatherers: A Late Holocene Example from Temperate Australia. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford

- ^ Lourandos, H. (1997) Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- JSTOR j.ctt24h987.12

- ^ Jourdan, Pablo. "Medieval Horticulture/Agriculture". Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Janick, Jules (2008). "Islamic Influences on Western Agriculture" (PDF). Purdue University. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ White, Lynn (1967). "The Life of the Silent Majority". In Hoyt, Robert S. (ed.). Life and Thought in the Early Middle Ages. University of Minnesota Press. p. 88.

- ^ Andersen, Thomas Barnebeck; Jensen, Peter Sandholt; Skovsgaard, Christian Volmar (December 2014). "The Heavy Plough and the Agricultural Revolution in Medieval Europe" (PDF). European Historical Economics Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- JSTOR 2596482.

- ISBN 978-0-520-03566-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-5052-7.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-521-30412-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-924776-9.

- ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-2213-3.

- ^ S2CID 154359726.

- ISBN 978-0-521-24711-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4262-1609-1.

- ^ Crosby, Alfred. "The Columbian Exchange". The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Wagner, Holly. "Super-Sized Cassava Plants May Help Fight Hunger In Africa". The Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 2013-12-08. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Wambugu, Florence; Wafula, John, eds. (2000). "Advances in Maize Streak Virus Disease Research in Eastern and Southern Africa". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ Chapman, Jeff (2000). "The Impact of the Potato". History Magazine (2). Archived from the original on 11 May 2000.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. "How the Potato Changed History". Smithsonian (November 2011). Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-28. Adapted from 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, by Charles C. Mann.

- ISBN 978-0-521-24548-7. Chapter 4

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2655. Retrieved 2 September 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2009.9.3.32.

- ^ Payne, F.G. "The British Plough: Some Stages in its Development" (PDF). British Agricultural History Society. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-87349-632-2.

- ISBN 978-0-85263-177-5.

- ISBN 978-1-61060-529-8.

- ^ "The Coprolite Industry". Cambridgeshire History. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Janick, Jules. "Agricultural Scientific Revolution: Mechanical" (PDF). Purdue University. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Reid, John F. (2011). "The Impact of Mechanization on Agriculture". The Bridge on Agriculture and Information Technology. 41 (3).

- ^ Suszkiw, Jan (November 1999). "Tifton, Georgia: A Peanut Pest Showdown". Agricultural Research magazine. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ "A Historical Perspective". International Fertilizer Industry Association. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ISBN 978-615-5225-63-5.

- PMID 17666391.

- ^ "Title 05 – Agriculture and rural development". Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ James, Clive (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Weasel, Lisa H. 2009. Food Fray. Amacom Publishing

- ^ Douglas, James S., Hydroponics, 5th ed. Oxford University Press, 1975. 1–3

- ^ "Towards Sustainable Production and Use of Resources: Assessing Biofuels" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. 16 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-31973-1.

- ^ "State of the World 2006". Worldwatch Institute. 2006.

- ^ "Ten worst famines of the 20th century". Sydney Morning Herald. 15 August 2011.

- ^ Hazell, Peter B.R. (2009). The Asian Green Revolution. IFPRI Discussion Paper. International Food Policy Research Institute. GGKEY:HS2UT4LADZD.

- ^ Barrionuevo, Alexei; Bradsher, Keith (8 December 2005). "Sometimes a Bumper Crop Is Too Much of a Good Thing". The New York Times.

- S2CID 3016610. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Paull, John (2011). "Attending the First Organic Agriculture Course: Rudolf Steiner's Agriculture Course at Koberwitz, 1924" (PDF). European Journal of Social Sciences. 21 (1): 64–70.

- ^ Paull, John (2014). "Lord Northbourne, the man who invented organic farming, a biography" (PDF). Journal of Organic Systems. 9 (1): 31–53.

Further reading

Surveys

- Civitello, Linda. Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People (Wiley, 2011) excerpt

- Federico, Giovanni. Feeding the World: An Economic History of Agriculture 1800–2000 (Princeton UP, 2005) highly quantitative

- Grew, Raymond. Food in Global History Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine (1999)

- Heiser, Charles B. Seed to Civilization: The Story of Food (W.H. Freeman, 1990)

- Herr, Richard, ed. Themes in Rural History of the Western World (Iowa State UP, 1993)

- Kiple, Kenneth F., and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas, eds. The Cambridge world history of food (2 vol Cambridge University Press, 2000) online.

- Mazoyer, Marcel, and Laurence Roudart. A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis (Monthly Review Press, 2006) Marxist perspective.

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. Food in world history (Routledge, 2023).

- Prentice, E. Parmalee. Hunger and History: The Influence of Hunger on Human History (Harper, 1939)

- Tauger, Mark. Agriculture in World History (Routledge, 2008)

- Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A history of food ( John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 800+ pp. online

- Whayne Jeannie, ed. (2024). The Oxford Handbook of Agricultural History. ISBN 978-0-19-092416-4. ; covers historiographical traditions within geographic regions across the world.

Premodern

- Bakels, C.C. The Western European Loess Belt: Agrarian History, 5300 BC – AD 1000 (Springer, 2009)

- Barker, Graeme, and Candice Goucher, eds. The Cambridge World History: Volume 2, A World with Agriculture, 12000 BCE–500 CE. (Cambridge UP, 2015)

- Bowman, Alan K. and Rogan, Eugene, eds. Agriculture in Egypt: From Pharaonic to Modern Times (Oxford UP, 1999)

- Cohen, M.N. The Food Crisis in Prehistory: Overpopulation and the Origins of Agriculture (Yale UP, 1977)

- Crummey, Donald and Stewart, C.C., eds. Modes of Production in Africa: The Precolonial Era (Sagem 1981)

- Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel (W.W. Norton, 1997)

- Duncan-Jones, Richard. Economy of the Roman Empire (Cambridge UP, 1982)

- Habib, Irfan. Agrarian System of Mughal India (Oxford UP, 3rd ed. 2013)

- Harris, D.R., ed. The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, (Routledge, 1996)

- Isager, Signe and Jens Erik Skydsgaard. Ancient Greek Agriculture: An Introduction (Routledge, 1995)

- Lee, Mabel Ping-hua. The economic history of china: with special reference to agriculture (Columbia University, 1921)

- Murray, Jacqueline. The First European Agriculture (Edinburgh UP, 1970)

- Oka, H-I. Origin of Cultivated Rice (Elsevier, 2012)

- Price, T.D. and A. Gebauer, eds. Last Hunters – First Farmers: New Perspectives on the Prehistoric Transition to Agriculture (1995)

- Srivastava, Vinod Chandra, ed. History of Agriculture in India (5 vols., 2014). From 2000 BC to present.

- Stevens, C.E. "Agriculture and Rural Life in the Later Roman Empire" in Cambridge Economic History of Europe, Vol. I, The Agrarian Life of the Middle Ages (Cambridge UP, 1971)

- Teall, John L. (1959). "The grain supply of the Byzantine Empire, 330–1025". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 13: 87–139. JSTOR 1291130.

- Yasuda, Y., ed. The Origins of Pottery and Agriculture (SAB, 2003) [ISBN missing]

Modern

- Collingham, E.M. The Taste of War: World War Two and the Battle for Food (Penguin, 2012)[ISBN missing]

- Kerridge, Erik. "The Agricultural Revolution Reconsidered." Agricultural History ( 1969) 43:4, 463–475. JSTOR 4617724, in Britain, 1750–1850

- Ludden, David, ed. New Cambridge History of India: An Agrarian History of South Asia Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine (Cambridge, 1999).

- McNeill, William H. (1999). "How the Potato Changed the World's History". Social Research. 66 (1): 67–83. PMID 22416329.

- Manning, Richard (2005). Against the Grain: How Agriculture Has Hijacked Civilization. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-1-4668-2342-6.

- Mintz, Sidney. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (Penguin, 1986)

- Reader, John. Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History (Heinemann, 2008) a standard scholarly history

- Salaman, Redcliffe N. The History and Social Influence of the Potato (Cambridge, 2010)

Europe

- Ambrosoli, Mauro. The Wild and the Sown: Botany and Agriculture in Western Europe, 1350–1850 (Cambridge UP, 1997)

- Brassley, Paul, Yves Segers, and Leen Van Molle, eds. War, Agriculture, and Food: Rural Europe from the 1930s to the 1950s (Routledge, 2012)

- Brown, Jonathan. Agriculture in England: A Survey of Farming, 1870–1947 (Manchester UP, 1987)

- Clark, Gregory (2007). "The long march of history: Farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209–1869" (PDF). Economic History Review. 60 (1): 97–135. S2CID 154325999.

- Dovring, Folke, ed. Land and labor in Europe in the twentieth century: a comparative survey of recent agrarian history (Springer, 1965)

- Gras, Norman. A history of agriculture in Europe and America (Crofts, 1925)

- Harvey, Nigel. The Industrial Archaeology of Farming in England and Wales (HarperCollins, 1980)

- Hoffman, Philip T. Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815 (Princeton UP, 1996)

- Hoyle, Richard W., ed. The Farmer in England, 1650–1980 (Routledge, 2013) online review[dead link]

- Kussmaul, Ann. A General View of the Rural Economy of England, 1538–1840 (Cambridge University Press, 1990)

- Langdon, John. Horses, Oxen and Technological Innovation: The Use of Draught Animals in English Farming from 1066 to 1500 (Cambridge UP, 1986)

- McNeill, William H. (1948). "The Introduction of the Potato into Ireland". Journal of Modern History. 21 (3): 218–221. S2CID 145099646.

- Moon, David. The Plough that Broke the Steppes: Agriculture and Environment on Russia's Grasslands, 1700–1914 (Oxford UP, 2014)

- Slicher van Bath, B.H. The Agrarian History of Western Europe, AD 500–1850 (Edward Arnold, reprint, 1963)

- Thirsk, Joan, et al. The Agrarian History of England and Wales (Cambridge University Press, 8 vols., 1978)

- Williamson, Tom. Transformation of Rural England: Farming and the Landscape 1700–1870 (Liverpool UP, 2002)

- Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina, Rachel Duffett, and Alain Drouard, eds. Food and war in twentieth century Europe (Ashgate, 2011)

North America

- Bidwell, Percy Wells, and John I. Falconer. History of agriculture in the northern United States, 1620–1860 (1925), massive scholarly history. online

- Cochrane, Willard W. The Development of American Agriculture: A Historical Analysis (University of Minnesota P, 1993)

- .

- Gras, Norman. A History of Agriculture in Europe and America, (F.S. Crofts, 1925)

- Gray, L.C. History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860 (P. Smith, 1933) Volume I online; Vol. 2

- Hart, John Fraser. The Changing Scale of American Agriculture. (University of Virginia Press, 2004)

- Hurt, R. Douglas. American Agriculture: A Brief History (Purdue UP, 2002)

- Mundlak, Yair (2005). "Economic Growth: Lessons from Two Centuries of American Agriculture". Journal of Economic Literature. 43 (4): 989–1024. .

- O'Sullivan, Robin. American Organic: A Cultural History of Farming, Gardening, Shopping, and Eating (University Press of Kansas, 2015)

- Rasmussen, Wayne D., ed. Readings in the history of American agriculture (University of Illinois Press, 1960)

- Robert, Joseph C. The story of tobacco in America (University of North Carolina Press, 1949)

- Russell, Howard. A Long Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming In New England (UP of New England, 1981)

- Russell, Peter A. How Agriculture Made Canada: Farming in the Nineteenth Century (McGill-Queen's UP, 2012)

- Schafer, Joseph. The social history of American agriculture (Da Capo, 1970 [1936])

- Schlebecker John T. Whereby we thrive: A history of American farming, 1607–1972 (Iowa State UP, 1972)

- Weeden, William Babcock. Economic and Social History of New England, 1620–1789 (Houghton, Mifflin, 1891)