User:Garygo golob/Natisone Valley dialect/sandbox

| Natisone Valley dialect | |

|---|---|

| nedìško narèčje | |

| Pronunciation | nɛˈdiːʃkɔ naˈɾɛt͡ʃjɛ |

| Native to | Venetian Slovenia) |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

| |

Early forms | Northwestern Slovene dialect

|

| Dialects |

|

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| IETF | sl-nedis |

Natisone Valley dialect | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

The Natisone Valley dialect (Natisone Valley: nedìško narèčje;

Classification

Natisone Valley dialect is a dialect of Slovene, an

Despite the facts, Natisone Valley dialect and standard Slovene are easily

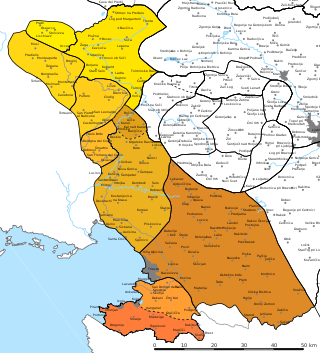

Geographic distribution

Dialect is spoken mainly in northeastern

Further division

Natisone Valley dialect is pretty uniform. The easternmost microdialects are the most different, having sounds /ə/ and /ʎ/, which are unknown to other microdialects and /m/ is sometimes used instead of /n/ at the end of a word. The biggest differences between microdialects are reflexes for Alpine Slovene *t’, which has almost merged with *č in the west, merging into /t͡ʃ/, with the first one usually being more palatalized. In the east, however, *t’ is still distinct and even pronounced as /t͡s/ at the end of a word.[11]

Accent

The Natisone Valley dialect has

Diacritics

Similarly to Standard Slovene, Natisone Valley dialect also has diacritics to denote accent. Accent is free and therefore it has to be denoted with a diacritic. There are three standard diacritics that are used, however, they do not show tonal oppositions.

The three diacritics are:[3][13]

- The grave ( ` ) indicates long vowel: à è ì ò ù (IPA /aː ɛː iː ɔː uː/).

- The acute ( ´ ) indicates short vowel: á é í ó ú (IPA /a ɛ i ɔ u/).

- The dot above( ˙ ) indicates extra-short vowel: ȧ ė ȯ u̇ (IPA /ă ɛ̆ ɔ̆ ŭ/).

Additionally, there is also the caron ( ˇ ), which indicates a vowel can be either long or short.

Phonology

Phonology of Natisone Valley dialect is similar to that of Standard Slovene. Two major exceptions are presence of diphthongs and existence of palatal sounds. The dialect is not uniform, though, and differences exist between eastern and western microdialects.[11]

Consonants

Natisone Valley dialect has 24 (in the east 25) distinct phonemes, in comparison to Standard Slovene 22. This is mostly due to the fact that it still has palatal /ɲ/, /ʎ/ and /tɕ/, which depalatalized in Standard Slovene, merging with already hard consonants.[14]

| Labial | Dental/ | Postalveolar | Dorsal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n

|

ɲ | ||

Plosive

|

voiceless | p | t

|

k | |

| voiced | b | d

|

(ɡ) | ||

Affricate

|

voiceless | ts | tʃ | tɕ | |

| voiced | (dʒ) | ||||

Fricative

|

voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x |

| voiced | z | ʒ | ɣ ~ ɦ | ||

Approximant

|

central | ʋ | j | ||

| lateral | l

|

(ʎ) | |||

Flap

|

ɾ | ||||

- Palatal /ʎ/ exists only in eastern microdialects, in western microdialects, it merged with /j/.

- Consonants /dʒ/ and /g/ are rare and only found in loanwords.

- Similarly to /l/ in Standard Slovene, both /v/ and /l/ can morphologically conditioned turn into [u̯], e. g. tràva 'grass' → tràunik 'grassland'.

- Consonant /tɕ/ has an allophone [ts] at the end of a word and [tsj] between vowels in the east. In the west, difference between /tɕ/ and /tʃ/ is barely noticeable.

Vowels

Phonology of Natisone Valley dialect is similar to that of Standard Slovene, but it has a seven vowel[15] (eastern microdialects eight vowel[16]) system, two of those are diphthongs.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | ɛ | (ə) | ɔ |

| Open | a | ||

| Diphthongs | ie~iɛ uo~uɔ | ||

From evolutionary perspective

Natisone Valley dialect experienced lengthening of non-final vowels and became undistinguishable from their long counterparts, except for *ò. Vowel *ě̄ then turned into ie, and *ō into uo. Long *ə̄ turned into aː. Other long mid vowels (*ē, *ę̄, *ò, *ǭ) turned into eː and oː, respectively. Vowels *ī, *ū and *ā stayed unchanged. Syllabic *ł̥̄ turned into uː and syllabic r̥̄ turned into ar in the west and ər in the east.

Vowel reduction is almost non-existent; there is some akanye, e-akanye and ikanye, but those examples are rare. The only more common feature is loss of final -i, but even this is not the case in some more remote villages, such as Montemaggiore/Matajur and Stermizza/Strmica. Short ə turned either into a or i in the west; in the east it stayed as ə only as a fill vowel. Cluster *ję- turned into i.

Palatal consonants stayed palatal, but *ĺ turned into j in the west and *t’ turned into *č́. Consonant *g turned into ɣ and into x at the end of a word.[11]

Morphology

Natisone Valley dialect still has neuter gender in singular, but it feminized in plural. It still has masculine and neuter o-stem declension, as well as feminine a-stem and i-stem declension. There is also masculine j-stem, as well as remains of feminine v-stem and neuter s-, t- and n-stem. These are mostly one word examples. It, however, has more archaic and pretty different declension patterns from Standard Slovene:[17]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Infinitive lost the final -i, but has the same accent as long infinitive.

Vocabulary

There are many loanwords borrowed from

| Natisone Valley | Standard Slovene | Meaning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writing | IPA | Writing | IPA | |

| kozá | [kɔˈza] | kóza | [ˈkɔ̀ːza] | 'goat' |

| kakùoša | [kaˈkúːɔʃa] | kokọ̑š | [kɔkóːʃ] | 'hen' |

| kandèla | [kanˈdɛ́ːla] | svẹ́ča | [ˈsvèːt͡ʃa] | 'candle' |

| golòb | [ɣɔˈlɔ́ːp] | golọ̑b | [gɔˈlɔ́ːp] | 'pigeon' |

| maglá | [maɣˈla] | meglȁ / mègla | [məgˈlá] / [mə̀gˈla] | 'fog' |

| ogìnj | [ɔˈɣiːɲ] | ógenj | [ˈɔ̀ːgən] | 'fire' |

| sér | [ˈsɛɾ] (west)

[ˈsəɾ] (east) |

sȉr | [ˈsɪ́ɾ] | 'cheese' |

| konác, kónc | [kɔˈnat͡s] (west)

[ˈkɔnt͡s] (east) |

kónec | [ˈkɔ̀ːnət͡s] | 'end' |

| ardèč | [aɾˈdɛ̀ːt͡ɕ] (west)

[əɾˈdɛ̀ːjt͡s] (east) |

rdȅč | [əɾˈdɛt͡ʃ] | 'red' |

| pandèjak | [panˈdɛ́ːjak] (west)

[panˈdɛ́ːʎk] (east) |

ponedẹ̑ljek | [pɔnɛˈdéːlɛk] | 'Monday' |

| ǧardìn | [d͡ʒaɾˈdíːn] | vȓt | [ˈvə́ɾt] | 'garden' |

| gjàndola | [ˈgjáːndɔla] | žlẹ́za | [ˈʒlèːza] | 'gland' |

Orthography

Orthography is mainly based on western microdialects. It has 26 letters, 25 of them are the same as in Slovene alphabet and added is ⟨ǧ⟩ for sound /dʒ/, which is in Standard Slovene written with ⟨dž⟩.

The standard Slovene orthography, used in almost all situations, uses only the letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet plus ⟨č⟩, ⟨š⟩, ⟨ž⟩, and ⟨ǧ⟩[19]:

| letter | phoneme | example word | word pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | /aː/

/a/ /ă/ |

kajšan 'what kind'

zastonj 'for free' zavaržen 'thrown away' |

[ˈkaːjʃan] kàjšan

[zasˈtɔːɲ] zastònj [zaˈvăɾʒɛn] zavȧržen |

| B b | /b/ | bližat 'approach' | [ˈbliːʒat] blìžat |

| C c | /t͡s/ | lizavac 'sucker' | [liˈzaːvat͡s] lizàvac |

| Č č | /t͡ʃ/

/t͡ɕ/ |

lačan 'hungry'

ardeč 'red' |

[ˈlaːt͡ʃan] làčan

[aɾˈdɛːt͡ɕ] ardèč |

| D d | /d/ | nadluoga 'menace' | [naˈdluːɔɣa] nadlùoga |

| E e | /ɛː/

/ɛ/ /ɛ̆/ |

guarenje 'burning'

sparjet 'stuck' tešč 'having empty stomach' |

[ɣuaˈɾɛːnjɛ] guarènje

[spaɾˈjɛt] sparjèt [tɛ̆ʃt͡ʃ] tėšč |

| F f | /f/ | fruoštih 'zajtrk' | [ˈfɾuːɔʃtix] frùoštih |

| G g | /ɣ/

/ɡ/ |

oginj 'fire'

gjandola 'gland' |

[ɔˈɣiːɲ] ogìnj

[ˈgjaːndɔla] gjàndola |

| Ǧ ǧ | /d͡ʒ/ | ǧardin 'garden' | [d͡ʒaɾˈdíːn] ǧardìn |

| H h | /x/ | komicih 'rally' | [kɔˈmiːt͡six] komìcih |

| I i | /iː/

/i/ |

zmiešan 'mixed'

lizat 'to lick' |

[ˈzmiːɛʃan] zmìešan

[liˈzaːt] lizàt |

| J j | /j/ | uarnjen 'returned' | [ˈu̯ăɾnjɛn] uȧrnjen |

| K k | /k/ | kompit 'work' | [ˈkɔmpit] kómpit |

| L l | /l/ | kompleano 'birthday' | [kɔmplɛ.aːnɔ] kompleàno |

| M m | /m/ | popunoma 'completely' | [pɔˈpuːnɔma] popùnoma |

| N n | /n/ | skupen 'common' | [ˈskuːpɛn] skùpen |

| O o | /ɔː/

/ɔ/ /ɔ̆/ |

narobe 'wrong'

lenoba 'lazy person' trop 'herd' |

[naˈɾɔːbɛ] naròbe

[lɛnɔˈba] lenobá [ˈtɾɔ̆p] trȯp |

| P p | /p/ | pekoč 'spicy' | [pɛˈkɔːt͡ʃ] pekòč |

| R r | /r/ | saru 'raw' | [saˈɾuː] sarù |

| S s | /s/ | ser 'cheese' | [ˈsɛɾ] sér |

| Š š | /ʃ/ | saršen 'hornet' | [saɾˈʃɛn] saršén |

| T t | /t/ | prat 'to wash' | [ˈpɾaːt] pràt |

| U u | /uː/

/u/ /ŭ/ /u̯/ |

težkuo 'hard'

opudan 'at noon' saku 'falcon' debeu 'fat' |

[tɛʒˈkuːɔ] težkùo

[ɔpuˈdaːn] opudàn [saˈkŭ] saku̇ [dɛˈbɛu̯] debèu |

| V v | /ʋ/ | težava 'problem' | [tɛˈʒaːʋa] težàva |

| Z z | /z/ | zvit 'to bend' | [ˈzʋiːt] zvìt |

| Ž ž | /ʒ/ | odluožt 'to put down' | [ɔdˈluːɔʃt] odlùožt |

The orthography thus underdifferentiates several phonemic distinctions:

- Stress, vowel length and tone are not distinguished, except with optional diacritics when it is necessary to distinguish between similar words with a different meaning.

- Consonant /g/ is not differentiated from its spirantizedversion, /ɣ/ and are both written as ⟨g⟩.

- Consonants /t͡ʃ/ and /t͡ɕ/ also are not differentiated, both being written as ⟨č⟩.

- Letter ⟨u⟩ is used to write syllabic /u/, as well as non-syllabic "false u" /u̯/.

Regulation

Natisone Valley dialect is unregulated, thus a fair degree of variation, both in pronunciation and in writing is common. Eastern microdialects are completely unstandardised, as most other Slovene dialects. In contrast, western microdialects have its own dictionary and grammar, written by Nino Špehonja in 2012.[3][20] The dictionary still allows many variations in writing, and consequently pronunciation. Main reason for different spellings is akanye, which is more common in some microdialects and less in other, e. g. the word for 'bonfire' can either be written as kries or krias.

References

- ^ Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- ^ Šekli, Matej. 2004. "Jezik, knjižni jezik, pokrajinski oz. krajevni knjižni jezik: Genetskojezikoslovni in družbenostnojezikoslovni pristop k členjenju jezikovne stvarnosti (na primeru slovenščine)." In Erika Kržišnik (ed.), Aktualizacija jezikovnozvrstne teorije na slovenskem. Členitev jezikovne resničnosti. Ljubljana: Center za slovenistiko, pp. 41–58, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Špehonja, Nino (2012a). Vocabolario Italiano - Nediško (PDF) (in Italian). Poligrafiche San Marco. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Logar (1996:11)

- ^ a b c "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Šekli (2018:327–328)

- ^ Toporišič, Jože. 1992. Enciklopedija slovenskega jezika. Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, p. 25.

- ^ Šekli (2018:326–328)

- ^ Logar (1996:148)

- ^ Zuljan Kumar (2018:108)

- ^ a b c Logar (1996:148–150)

- ^ Šekli (2018:326)

- ^ Špehonja (2012b:22)

- ^ Logar (1996:7–9)

- ^ a b c Logar (1996:254)

- ^ a b c Šekli (2007:409–410)

- ^ Špehonja (2012b:45–58)

- ISBN 978-961-282-010-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-03-18. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ Špehonja (2012b:19–28)

- ^ Špehonja (2012b)

Bibliography

- ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- Šekli, Matej (2007). Fonološki opis govora vasi Jevšček pri Livku nadiškega narečja slovenščine (in Slovenian). Vol. 1–2. Ljubljana. pp. 409–427.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Tipologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. )

- Špehonja, Nino (2012b). Nediška gramatika (in Italian). Poligrafice San Marco.

- Zuljan Kumar, Danila (27–29 September 2018). Žele, Andreja; Šekli, Matej (eds.). Slovenski jezik v Nadiških dolinah (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Zveza društev Slavistično društvo Slovenije. pp. 108–121. ISBN 978-961-6715-27-0. Retrieved 9 August 2022.)

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link

Further reading

- Nino Špehonja, Nediška gramatika, grammar of Natisone Valley dialect (in Italian).

- Nino Špehonja, Vocabolario Italiano-Nediško, Italian-Natisone Valley dialect dictionary (in Italian).