Ecological light pollution

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

Ecological light pollution

The effect that artificial light has upon organisms is highly variable,

Through the various effects that

The introduction of artificial light at night is one of the most drastic

Natural light cycles

The introduction of artificial light disrupts several natural light cycles that arise from the movements of the

Diurnal (solar) cycle

The most obvious change in introducing light at night is the end of darkness in general. The day/night cycle is probably the most powerful environmental behavioral signal, as almost all animals can be categorized as

Seasonal (solar) cycles

The

Lunar cycles

The behavior of some animals (e.g. coyotes,[9] bats,[10] toads,[11] insects) is keyed to the lunar cycle. Near city centers the level of skyglow often exceeds that of the full moon,[12] so the presence of light at night can alter these behaviors, potentially reducing fitness.

Cloud coverage

In pristine areas, clouds blot out the stars and darken the night sky, resulting in the darkest possible nights. In

Effects of light pollution on individual organisms

Terrestrial Environment

Insects

The attraction of insects to artificial light is one of the most well known examples of the effect of light at night on organisms. When insects are attracted to lamps they can be killed by exhaustion or contact with the lamp itself, and they are also vulnerable to predators like bats.[5]

Insects are affected differently by the varying wavelengths of light, and many species can see

The compound eye of moths results in fatal attraction to light.[15]

Light pollution may hamper the mating rituals of fireflies, once they depend on their own light for courtship, resulting in decreased populations.[17][18][19]

Fireflies are charismatic (which is a rare quality amongst insects) and are easily spotted by nonexperts, providing thus good flagship species to attract public attention; good investigation models for the effects of light on nocturnal wildlife; and finally, due to their sensibility and rapid response to environmental changes, good bioindicators for artificial night lighting.[20]

Birds

Lights on tall structures can disorient

Similar disorientation has also been noted for bird species migrating close to offshore production and drilling facilities. Studies carried out by Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij b.v. (NAM) and Shell have led to development and trial of new lighting technologies in the North Sea. In early 2007, the lights were installed on the Shell production platform L15. The experiment proved a great success since the number of birds circling the platform declined by 50–90%.[56] Juvenile seabirds may also be disoriented by lights as they leave their nests and fly out to sea causing events of high mortality.[23] To minimise mortality rescue programs are conducted on many islands giving a second chance to thousands of seabird fledglings. [24]

Birds migrate at night for several reasons. Save water from dehydration in hot day flying and part of the bird's navigation system works with stars in some way. With city light outshining the night sky, birds (and also about mammals) no longer navigate by stars.[25]

Ceilometers (searchlights) can be particularly deadly traps for birds,[26] as they become caught in the beam and risk exhaustion and collisions with other birds. In the worst recorded ceilometer kill-off, on October 7–8, 1954, 50,000 birds from 53 different species were killed at Warner Robins Air Force Base.[27]

Turtles

Lights from seashore developments repel nesting Sea turtle mothers, and their hatchlings are fatally attracted to street and hotel lights rather than to the ocean.[28]

Plants

Artificial lighting has many negative impacts on trees and plants, particularly in fall and autumn phenology. Trees and herbaceous plants rely on the photoperiod, or the amount of time in a day where sunlight is available for photosynthesis, to help determine the changing seasons. When the hours of sunlight decrease, plants can recognize that autumn is underway and begin to make preparations for winter dormancy. For example, deciduous trees shift the colour of their leaves to maximize different wavelengths of light that are more prevalent in the fall before eventually dropping them as light becomes too scarce for photosynthesis to be worthwhile. When deciduous trees are exposed to light pollution, they mistake the artificial light for sunlight and retain their green leaves later into the autumn season. This can be dangerous for the tree, as it wastes energy trying to photosynthesize that should be preserved for winter survival. Light pollution can also cause leaf stoma to remain open into the night, which leaves the tree vulnerable to infection and disease.[29]

Similarly, light pollution in the spring can also be dangerous for trees and herbaceous plants. Artificial light causes plants to think that spring has arrived and it is time to begin producing leaves for photosynthesizing again. However, temperatures may not yet be warm enough to support the new leaf buds, and they are susceptible to frost, which can impair future leaf production. Small herbaceous plants that are exposed to artificial lighting potentially face a greater risk, as more of their body is illuminated. Therefore, only the root system is protected, and could potentially not be enough to sustain the whole plant as it tries to remain green through the fall and winter.[30]

Aquatic Environment

Ecological light pollution has also critical effects on marine ecosystems. [31]

Zooplankton

Zooplankton (e.g. Daphnia) exhibit diel vertical migration. That is, they actively change their vertical position inside of lakes throughout the day. In lakes with fish, the primary driver for their migration is light level, because small fish visually prey on them. The introduction of light through skyglow reduces the height to which they can ascend during the night.[32] Because zooplankton feed on the phytoplankton that form algae, the decrease in their predation upon phytoplankton may increase the chance of algal blooms, which can kill off the lakes' plants and lower water quality.

Fish

Light pollution impacts migration in some species of fish. For example, juvenile chinook salmon are attracted to and slowed down by artificial light. It is possible that artificial light draws them closer to the shoreline, where they face a greater risk of predation from birds and mammals. Artificial lighting also attracts a greater density of piscivorous fish, which have an advantage due to the slower movement of the juvenile fish.[33] Light pollution also has impacts on the hormonal functioning of some fish; European perch and roach both experience reductions in the production of reproductive hormones when exposed to artificial lighting in a rural environment.[34] Artificial light has also been shown to cause disruptions to fish (and zooplankton) in the high Arctic, where fishing boats with lights resulted in a lack of fish up to 200 metres below the water's surface.[35]

Humans

At the turn of the century it was discovered that

Other human health effects may include increased

Effects of different wavelengths

The effect that artificial light has upon organisms is

Polarized light pollution

Artificial planar surfaces, such as

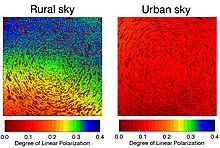

In the night, the polarization of the moonlit sky is very strongly reduced in the presence of urban light pollution, because scattered urban light is not strongly polarized.[49] Since polarized moonlight is believed to be used by many animals for navigation, this screening is another negative effect of light pollution on ecology.

Prevents and Controls

To regulate and manage the problem of light pollution, it needs to establish a mature management system. Based on Zhou's studies, posing regulations such as green lighting, strengthening the propaganda and education by governors could help stop or reduce the adverse impacts of light pollution.[50]

See also

References

- ISSN 1540-9295.

- ISBN 978-1-55963-128-0.

- PMID 19165374.

- ^ JSTOR 2389972.

- S2CID 53108567.

- S2CID 5074170.

- S2CID 10616727.

- JSTOR 2426745.

- S2CID 85156702.

- S2CID 53169271.

- ^ PMID 21399694.

- .

- ^ Gray, R. (29 May 2013). "Fatal Attraction: Moths Find Modern Street Lamps Irresistible". Online Newspaper. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ Kenneth D. Frank (1988). "Impact of outdoor lighting on moths". Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 42: 63–93. Archived from the original on 2006-06-17.

- ^ "Polarized Light Pollution Leads Animals Astray". UPI Space Daily. United Press International. 13 January 2009.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (August 14, 2014). "The Science in a Twinkle of Nighttime in the South". The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- PMID 29415023.

- S2CID 36670391.

- ISSN 1676-0603.

- S2CID 11925316.

- S2CID 213571293.

- hdl:10261/45133.

- hdl:10400.3/4515.

- ^ "در سایهی نورها". پریسا باجلان (in Persian). 2020-10-15. Archived from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ^ "10000 birds trapped in the World Center light beams". Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- JSTOR 4081744.

- ^ Salmon, Michael (2003). "Artificial night lighting and sea turtles" (PDF). ResearchGate.

- S2CID 73529155.

- PMID 27358370.

- hdl:11568/1165839.

- ^ Marianne V. Moore; Stephanie M. Pierce; Hannah M. Walsh; Siri K. Kvalvik; Julie D. Lim (2000). "Urban light pollution alters the diel vertical migration of Daphnia" (PDF). Verh. Internat. Verein. Limnol. 27: 1–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-21. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- S2CID 229392819.

- PMID 29686874.

- PMID 32139805.

- PMID 10632589.

- ^ Schulmeister, K.; Weber, M.; Bogner, W.; Schernhammer, E. (2002). "Application of melatonin action spectra on practical lighting issues". Final Report. The Fifth International LRO Lighting Research Symposium, Light and Human Health. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- PMID 11604479.

- PMID 11604480.

- ISBN 0-89603-277-9

- ISBN 0-521-43686-9

- ^ L. Pijnenburg, M. Camps and G. Jongmans-Liedekerken, Looking closer at assimilation lighting, Venlo, GGD, Noord-Limburg (1991)

- .

- S2CID 4204514.

- hdl:10261/177341.

- S2CID 18988450.

- ^ International Dark-Sky Association (2010). "Visibility, Environmental, and Astronomical Issues Associated with Blue-Rich White Outdoor Lighting" (PDF). IDA White Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- doi:10.1890/080129.

- .

- ISBN 978-94-6252-210-7.