Protestantism in Germany

The religion of Protestantism (German: Protestantismus), a form of Christianity, was founded within Germany in the 16th-century Reformation. It was formed as a new direction from some Roman Catholic principles. It was led initially by Martin Luther and later by John Calvin.[3]

History

The Protestant

Political effects

Separation of church and state

In the early 1500s, the

Rebirth of political Protestantism

In the 19th century,

Nazi Germany

During the

Communism and the German Democratic Republic, 1949–1990

In the initial years of

| Protestants in East Germany 1949–1989 | No. of members | No. parishes | No. of pastors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lutheran (Werner Leich, Chairman) | 6,435,000 | 7,347 | 4,161 |

| Methodist (Rüdiger Minor, Bishop of Dresden) | 28,000 | 400 | 140 |

| Baptist Federation (Manfred Suit, President) | 20,000 | 222 | 130 |

| Reformed (HansJürgen Sievers, Chairman) | 15,000 | 24 | 20 |

| Old Lutheran (Johannes Zellmer, President) | 7,150 | 27 | 22 |

| Total | 6,505,150 | 8,020 | 4,473 |

Economic effects

The initial effect of the Protestant revolution in Germany was to facilitate the entry of entrepreneurship with the decline of feudalism.[15] The Lutheran literature dispersed throughout Germany after the Reformation called for the elimination of clerical tax exemptions and the economic privileges granted to religious institutions.[16] Through the 16th century, however, the Protestant movement brought with it wealthy and influential Lutheran princes who formed a new social class.[7]

Social and cultural effects

Art

When the Reformation occurred, the art industry was declining in Germany; however, it provided a new inspiration for graphic arts, sculptures and paintings.[17] Protestant churches displayed medieval images, along with uniquely Lutheran artistic traditions, such as the Wittenberg workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder and Lucas Cranach the Younger.[18] The Protestant movement brought a new variation of figural sculptures, portraits, artwork and illustrations to the interiors of German churches.[19]

-

Portrait of Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach, 1562

-

Portrait of Lucas Cranach the Elder

-

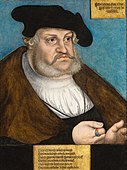

Portrait ofFrederick the Wiseby Lucas Cranach the Elder

-

Bronze sculpture of Luther, 1868, Worms, Germany

Music

Martin Luther's early reforms included an emphasis on the value music provides as an aid to worship.

Education

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

In the immediate post-Reformation and subsequent decades, the Lutheran principle of

Literature

In the years after the Reformation, Luther and his followers utilised the

Wider culture and theology

The Protestant church has influenced changes in wider culture in Germany, contributing to the debate around bioethics and stem cell research.[25] The Protestant leadership in Germany is divided on the issue of stem cell research; however, those opposing liberalising laws have characterised it as a threat to the sanctity of human life.[26] Within the German Democratic Republic, the Federation of Evangelical Churches, formed in June 1969 and lasting until April 1991, was where questions of morality were determined.[12]

Architecture

The Protestant church has influenced German architecture. Among adherents to Protestantism in Germany were engineers, craftsmen and architects, enabling Lutheran constructions.[18] The earliest Protestant constructions were in the 17th century, where the castles built along Germany's Middle Rhine were inhabited by Protestant archbishops, joined only by nobles and princes.[27] In the later centuries, separate church buildings were constructed along the Rhine region, due to controversial marriage laws that mandated Protestants and Catholics marry separately.[27] The spreading of Protestant architecture was slower in other parts of Germany, however, such as the city of Cologne where its first Protestant church was constructed in 1857.[28] Large Protestant places of worship were commissioned across Germany, such as the Garrison Church in the city of Ulm built in 1910 which could hold 2,000 congregants.[29] In the early 1920s, architects such as Gottfried Böhm and Otto Bartning were involved in changing Protestant architecture towards modern constructions.[28] An example of this new form of architecture was the Protestant Church of the Resurrection built in the city of Essen in 1929 by Bartning.[28]

Media

The Protestant church published five regional papers throughout the GDR, including Die Kirche (Berlin, circulation 42,500; also in a Greifswald edition), Der Sonntag (Dresden, circulation 40,000), Mecklenburgische Kirchenzeitung (Mecklenburg, circulation 15,000), Glaube und Heimat (Jena, circulation 35,000), and Potsdamer Kirche (Potsdam, circulation 15,000).[14]

Influences on Christianity within Germany

The reformation itself was grounded in a rebellion against the German Catholic church, emphasizing the primacy of the Bible, the abolition of the Catholic ritualistic mass and a rejection of clerical celibacy.[30] The 19th century saw movements within German Protestantism involving practical devotion and spiritual energy. The 20th century saw the creation of new Protestant organisations, such as the Evangelical Alliance, YMCA, and the German Student Christian movement, whose active participation involved church adherents from other nations.[6]

See also

- Religion in Germany

- Baptists in Germany

- Roman Catholicism in Germany

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Germany

- Oriental Orthodoxy in Germany

- Culture of Europe

- Religion in Europe

- European wars of religion

- Criticism of Protestantism

- Protestantism and Islam

- Protestantism by country

References

- ^ "Religionszugehörigkeiten 2022".

- ^ "Kirchenmitglieder: 47,45 Prozent".

- ^ Elton, G., & Pettegree, A. (1999). Reformation Europe, 1517-1559 (pp. 30-84). Oxford: Blackwell.

- ^ Scribner, R. W. (1987). Popular culture and popular movements in Reformation Germany. A&C Black.

- ^ Dixon, C. S. (2008). The Reformation in Germany (Vol. 4). John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ a b c d e f Littell, F. (2005). Illustrated history of Christianity (2nd ed., pp. 151–407). New York: Continuum.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hughes, M. (1992). Early Modern Germany, 1477–1806 (1st ed., pp. 4–190). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- ^ Eberle, E. (2016). Church and state in Western society (1st ed., pp. 32–100). London: Routledge.

- ^ a b Probst, C. (2012). Demonizing the Jews (pp. 3–98). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ^ doi:10.2307/1431915

- ^

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ramet, S. (1998). Nihil Obstat: Religion, Politics, and Social Change in East-Central Europe (2nd ed., pp. 67–101). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- ^ a b c Tyndale, W. (2016). Protestants in Communist East Germany: In the Storm of the World (1st ed., pp. 4–95). New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b c Solberg, R. (1961). God and Caesar in East Germany. The conflicts of Church and State in East Germany since 1945, etc. (1st ed., pp. 235–260). Michigan: Macmillan University of Michigan.

- ^ Ekelund, Jr., R., Hébert, R., & Tollison, R. (2002). An Economic Analysis of the Protestant Reformation. Journal Of Political Economy, 110(3), 646-671. doi: 10.1086/339721

- ^ Seabold, S., & Dittmar, J. (2015). Media, Markets and Institutional Change: Evidence from the Protestant Reformation. Centre For Economic Performance, 2, 6-43.

- ^ Christensen, C. (1973). "The Reformation and the Decline of German Art". Central European History, 6(3), 207–232. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4545672

- ^ a b Heal, B. (2018). A Magnificent Faith: Art and Identity in Lutheran Germany (2nd ed., pp. 23–79). New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Smith, J. (1994). German sculpture of the later Renaissance, c. 1520-1580: art in an age of uncertainty (1st ed., pp. 23–78). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Oettinger, R. (2001). Music as Propaganda in the German Reformation (1st ed., pp. 4–350). New York: Routledge.

- ^ Etherington, C. (1978). Protestant worship music. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- ^

- ^ Tuffs, A. (2001). "Germany debates embryonic stem cell research". BMJ, 8, 323.

- ^ a b Taylor, R. (1998). The Castles of the Rhine: Recreating the Middle Ages in Modern Germany (1st ed., pp. 32–100). Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- ^ a b c James-Chakraborty, K. (2000). German Architecture for a Mass Audience (2nd ed., pp. 3–158). New York: Routledge.

- ^ Maciuika, J. (2008). Before the Bauhaus: Architecture, Politics and the German State, 1890–1920 (1st ed., pp. 12–340). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Seabold, S., & Dittmar, J. (2015). Media, Markets and Institutional Change: Evidence from the Protestant Reformation. Centre For Economic Performance, 2, 6–43.

Further reading

- Littel, Franklin (2005). Illustrated History of Christianity. New York, United States: The Continuum. p. 151.

- Roper, Lyndal (2018). Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet. New York, United States: Random House. p. 161.