Christianity in the Middle Ages

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Christianity in the Middle Ages covers the history of Christianity from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (c. 476). The end of the period is variously defined - depending on the context, events such as the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Christopher Columbus's first voyage to the Americas in 1492, or the Protestant Reformation in 1517 are sometimes used.[1]

In Christianity's ancient

Early Middle Ages (476–799)

The Early Middle Ages commenced when the last western Roman emperor was deposed in 476, to be followed by the barbarian king, Odoacer, to the coronation of Charlemagne as "Emperor of the Romans" by Pope Leo III in Rome on Christmas Day, 800. The year 476, however, is a rather artificial division.[3] In the East, Roman imperial rule continued through the period historians now call the Byzantine Empire. Even in the West, where imperial political control gradually declined, distinctly Roman culture continued long afterwards; thus historians today prefer to speak of a "transformation of the Roman world" rather than a "fall of the Roman Empire."

The advent of the Early Middle Ages was a gradual and often localised process whereby, in the West, rural areas became power centres whilst urban areas declined. With the Muslim invasions of the seventh century, the Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) areas of Christianity began to take on distinctive shapes. Whereas in the East the Church maintained its strength, in the West the bishops of Rome (i.e., the Popes) were forced to adapt more quickly and flexibly to drastically changing circumstances. In particular whereas the bishops of the East maintained clear allegiance to the Eastern Roman Emperor, the bishop of Rome, while maintaining nominal allegiance to the Eastern Emperor, was forced to negotiate delicate balances with the "barbarian rulers" of the former Western provinces. Although the greater number of Christians remained in the East, the developments in the West would set the stage for major developments in the Christian world during the later centuries.[4]

Early Medieval Papacy

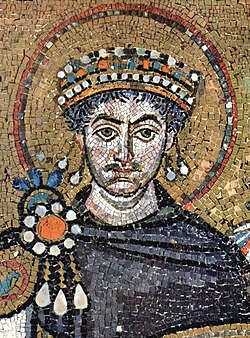

After the Italian peninsula fell into warfare and turmoil due to the barbarian tribes, the Emperor Justinian I attempted to reassert imperial dominion in Italy from the East, against the Gothic aristocracy. The subsequent campaigns were more or less successful, and an Imperial Exarchate was established for Italy, but imperial influence was limited. The Lombards then invaded the weakened peninsula, and Rome was essentially left to fend for itself. The failure of the East to send aid resulted in the popes themselves feeding the city with grain from papal estates, negotiating treaties, paying protection money to Lombard warlords, and, failing that, hiring soldiers to defend the city.[5] Eventually the popes turned to others for support, especially the Franks.

Spread Beyond the Roman Empire

As the political boundaries of the Roman Empire diminished and then collapsed in the West, Christianity spread beyond the old borders of the Empire and into lands that had never been under Rome.

Irish Missionaries

Beginning in the fifth century, a unique culture developed around the Irish Sea consisting of what today would be called Wales and Ireland. In this environment, Christianity spread from Roman Britain to Ireland, especially aided by the missionary activity of St. Patrick with his first-order of 'patrician clergy', active missionary priests accompanying or following him, typically Britons or Irish ordained by him and his successors.[6] Patrick had been captured into slavery in Ireland and, following his escape and later consecration as bishop, he returned to the isle that had enslaved him so that he could bring them the Gospel. Soon, Irish missionaries such as Columba and Columbanus spread this Christianity, with its distinctively Irish features, to Scotland and the Continent. One such feature was the system of private penitence, which replaced the former practice of penance as a public rite.[7]

Anglo-Saxons, English

Although southern Britain had been a Roman province, in 407 the imperial legions left the isle, and the Roman elite followed. Some time later that century, various barbarian tribes went from raiding and pillaging the island to settling and invading. These tribes are referred to as the "Anglo-Saxons", predecessors of the English. They were entirely pagan, having never been part of the Empire, and although they experienced Christian influence from the surrounding peoples, they were converted by the mission of St. Augustine sent by Pope Gregory the Great. The majority of the remaining British population converted from Christianity back to their Pagan roots. Contrary to popular belief, the conversion of Anglo-Saxons to Christianity was incredibly slow. The Anglo-Saxons had little interest in changing their religion and even initially looked down upon Christianity due to conquering the Christian British people decades earlier.

It took almost a century to convert only the aristocracy of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity with many still converting back to Paganism. After this, the common folk took a few hundred more years to convert to Christianity and their reasoning for converting was in large part due to the nobility.

Franks

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of

Frisians of the Low Countries

In 698, the

Much of Willibrord's work was wiped out when the pagan

Characteristics and movements

Iconoclasm

Apocalyptic thought

According to historian James T. Palmer, in the early Middle Ages, Christians had a string emphasis on the immanent return of Christ, judgement, and the end of the world, stimulating the desire "to get it right" before the judgment:

"...apocalyptic thought in the early Middle Ages was commonplace and mainstream, and an important factor in the way that people conceptualised, stimulated and directed change. ... Apocalyptic thought, understood properly, essentially becomes a powerful part of reform discourse about how best to direct people – individually and collectively – towards a better life on Earth. Even when people saw divine punishment, maybe in attacks by Huns or raids by Vikings, they felt compelled to change behaviour, rather than to wallow in fatalistic self-pity."

— James T. Palmer, The Apocalypse in the early Middle Ages[12]

High Middle Ages (800–1300)

Carolingian Renaissance

The

Growing tensions between East and West

The cracks and fissures in Christian unity which led to the East-West Schism started to become evident as early as the fourth century. Cultural, political, and linguistic differences were often mixed with the theological, leading to schism.

The transfer of the Roman capital to Constantinople inevitably brought mistrust, rivalry, and even jealousy to the relations of the two great sees, Rome and Constantinople. It was easy for Rome to be jealous of Constantinople at a time when it was rapidly losing its political prominence. Estrangement was also helped along by the German invasions in the West, which effectively weakened contacts. The rise of Islam with its conquest of most of the Mediterranean coastline (not to mention the arrival of the pagan Slavs in the Balkans at the same time) further intensified this separation by driving a physical wedge between the two worlds. The once homogenous unified world of the Mediterranean was fast vanishing. Communication between the Greek East and Latin West by the 600s had become dangerous and practically ceased.[13]

Two basic problems – the nature of the

By the fifth century, Christendom was divided into a pentarchy of five sees with Rome accorded a primacy. The four Eastern sees of the pentarchy, considered this determined by canonical decision and did not entail hegemony of any one local church or patriarchate over the others. However, Rome began to interpret her primacy in terms of sovereignty, as a God-given right involving universal jurisdiction in the Church. The collegial and conciliar nature of the Church, in effect, was gradually abandoned in favour of supremacy of unlimited papal power over the entire Church.

These ideas were finally given systematic expression in the West during the

The other major irritant to Eastern Christendom was the Western use of the filioque clause—meaning "and the Son"—in the Nicene Creed . This too developed gradually and entered the Creed over time. The issue was the addition by the West of the Latin clause filioque to the Creed, as in "the Holy Spirit... who proceeds from the Father and the Son," where the original Creed, sanctioned by the councils and still used today, by the Eastern Orthodox simply states "the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father." The Eastern Church argued that the phrase had been added unilaterally and, therefore, illegitimately, since the East had never been consulted.[15] In the final analysis, only another ecumenical council could introduce such an alteration. Indeed, the councils, which drew up the original Creed, had expressly forbidden any subtraction or addition to the text. In addition to this ecclesiological issue, the Eastern Church also considered the filioque clause unacceptable on dogmatic grounds. Theologically, the Latin interpolation was unacceptable since it implied that the Spirit now had two sources of origin and procession, the Father and the Son, rather than the Father alone.[16]

Photian Schism

In the 9th century AD, a controversy arose between Eastern (Byzantine, later Orthodox) and Western (Latin, later Roman Catholic) Christianity that was precipitated by the opposition of the Roman

The controversy also involved Eastern and Western ecclesiastical jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church, as well as a doctrinal dispute over the

Photius did provide concession on the issue of jurisdictional rights concerning Bulgaria and the papal legates made do with his return of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, however, was purely nominal, as Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already secured for it an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Bulgaria, the papacy was unable to enforce any of its claims.

East-West Schism

The

The "official" schism in 1054 was the excommunication of Patriarch

Both groups are descended from the Early Church, both acknowledge the apostolic succession of each other's bishops, and the validity of each other's sacraments. Though both acknowledge the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, Eastern Orthodoxy understands this as a primacy of honour with limited or no ecclesiastical authority in other dioceses.

The Orthodox East perceived the Papacy as taking on monarchical characteristics that were not in line with the church's traditional relationship with the emperor.

The final breach is often considered to have arisen after the capture and sacking of Constantinople by the

Monastic Reform

Cluny

From the

Cîteaux

The next wave of monastic reform came with the

Mendicant Orders

A third level of monastic reform was provided by the establishment of the

Investiture Controversy

The

Bishops collected revenues from estates attached to their bishopric. Noblemen who held lands (fiefdoms) hereditarily passed those lands on within their family. However, because bishops had no legitimate children, when a bishop died it was the king's right to appoint a successor. So, while a king had little recourse in preventing noblemen from acquiring powerful domains via inheritance and dynastic marriages, a king could keep careful control of lands under the domain of his bishops. Kings would bestow bishoprics to members of noble families whose friendship he wished to secure. Furthermore, if a king left a bishopric vacant, then he collected the estates' revenues until a bishop was appointed, when in theory he was to repay the earnings. The infrequence of this repayment was an obvious source of dispute. The Church wanted to end this lay investiture because of the potential corruption, not only from vacant sees but also from other practices such as simony. Thus, the Investiture Contest was part of the Church's attempt to reform the episcopate and provide better pastoral care.

Pope Gregory VII issued the .

Crusades

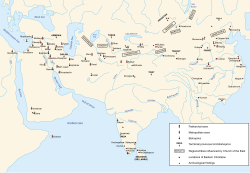

The Crusades were a series of military conflicts conducted by Christian knights for the defense of Christians and for the expansion of Christian domains. Generally, the Crusades refer to the campaigns in the Holy Land sponsored by the papacy against invading Muslim forces. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, as well as the campaigns of Teutonic knights against pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe (see

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries. Thereafter, Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the

In the First Crusade, after nine months of war of attrition, a traitor named Firuz led the Franks into the city of Antioch in 1098. However, after less than a week, the might of an army numbering hundreds of thousands led by Kerbogah arrived and besieged the city. The crusaders reportedly had only 30,000 men and the Turks outnumbered them three to one; facing desertion and starvation, Bohemond was officially chosen to lead the crusader army in June 1098. On the morning of 28 June, the crusader army, consisting of mostly dismounted knights and foot soldiers because most horses had died at that point, sallied out to attack the Turks, and broke the line of Kerbogah's army, allowing the crusaders to gain complete control of the Antioch and its surroundings.[17] The Second Crusade occurred in 1145 when Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces. Jerusalem would be held until 1187 and the Third Crusade, famous for the battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, begun by Innocent III in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Land but was soon subverted by Venetians who used the forces to sack the Christian city of Zara. Innocent excommunicated the Venetians and crusaders.[citation needed] Eventually the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, but due to strife which arose between them and the Byzantines,[citation needed] the crusaders sacked Constantinople and other parts of Asia Minor, rather than proceeding to the Holy Land, effectively establishing the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Minor. This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy; later crusades were sponsored by individuals. Thus, though Jerusalem was held for nearly a century and other strongholds in the Near East would remain in Christian possession much longer, the crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms. The Europeans' defeat can in no small part be attributed to the excellent martial prowess of the Mameluke and Turks, who both utilized agile mounted archers in open battle and Greek fire in siege defense. However, ultimately it was the inability of the Crusader leaders to command coherently that doomed the military campaign. In addition, the failure of the missionaries to convert the Mongols to Christianity thwarted the hope for a Tartar- Frank alliance. The Mongols later on converted to Islam.[18] Islamic expansion into Europe would renew and remain a threat for centuries, culminating in the campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent in the sixteenth century. On the other hand, the crusades in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily eventually led to the demise of Islamic power in the regions; the Teutonic knights expanded Christian domains in Eastern Europe, and the much less frequent crusades within Christendom, such as the Albigensian Crusade, achieved their goal of maintaining doctrinal unity.[19]

Medieval inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition officially started in 1231, when Pope Gregory IX appointed the first inquisitors to serve as papal agents to remove heresy. Heretics were seen as a menace to the Church and the first group dealt with by the inquisitors were the Cathars of southern France. Heresy had been seen as a recurring problem for the medieval Church since the burning of heretics at Orlèans in 1022.[20] The main tool used by the inquisitors was interrogation that often featured the use of torture followed by having heretics burned at the stake. After about a century this first medieval inquisition came to a conclusion. A new inquisition called the Spanish Inquisition was created by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in order to consolidate their rule. This new inquisition was separated from the Roman Church and the inquisition that came before it. At first it was primarily directed at Jews who converted to Christianity because many were suspicious that they did not actually convert to Christianity. Later it spread to targeting Muslims and the various peoples of the Americas and Asia.[21] The inquisitions in combination with the Albigensian Crusade were fairly successful in suppressing heresy.

Rise of universities

Modern western universities have their origins directly in the Medieval Church.

Spread of Christianity

Conversion of the Slavs

Though by 800 western Europe was ruled entirely by Christian kings, central and eastern Europe remained areas of missionary activity. In the ninth century SS.

In the ninth and tenth centuries Christianity made great inroads into central and eastern Europe. The evangelisation, or Christianisation, of the Slavs was strongly supported by one of Byzantium's most learned churchmen of the

The two brothers spoke the

Some of the disciples, namely

The Serbs were accounted Christian as of about 870.[29][30] Serbian patriarchate was recognised by Constantinople in 1346.

The

The missionaries to the Slavs had subsequent success in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin as the Roman priests did, or Greek.

Mission to Great Moravia

When king

When friction developed, the brothers, unwilling to be a cause of dissension among Christians, travelled to Rome to see the Pope, seeking an agreement that would avoid quarrelling between missionaries in the field. Constantine entered a monastery in Rome, taking the name Cyril, by which he is now remembered. However, he died only a few weeks thereafter.

Pope Adrian II gave Methodius the title of Archbishop of Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia) and sent him back in 869, with jurisdiction over all of Moravia and Pannonia, and authorisation to use the Slavonic Liturgy. Soon, however, Prince Ratislav, who had originally invited the brothers to Moravia, died, and his successor did not support Methodius. In 870 the Frankish king Louis and his bishops deposed Methodius at a synod at Ratisbon, and imprisoned him for a little over two years. Pope John VIII secured his release, but instructed him to stop using the Slavonic Liturgy.

In 878, Methodius was summoned to Rome on charges of heresy and using Slavonic. This time Pope John was convinced by the arguments that Methodius made in his defence and sent him back cleared of all charges, and with permission to use Slavonic. The Carolingian bishop who succeeded him, Witching, suppressed the Slavonic Liturgy and forced the followers of Methodius into exile. Many found refuge with Boris of Bulgaria (852–889), under whom they reorganised a Slavic-speaking Church, instead of Greek. Meanwhile, Pope John's successors adopted a Latin-only policy which lasted for centuries.

Conversion of Bulgaria

Some of the disciples, namely St. Kliment, St. Naum who were of noble

Bulgarian church was almost always aligned with the Orthodox Christianity after the split of the Eastern and Western churches in 1050, with occasional and temporary decades long union with the Roman church during the reign of Kaloyan in the beginning of the 13th century.

Conversion of the Rus'

The success of the conversion of the Bulgarians facilitated the conversion of other

The traditional event associated with the conversion of Russia is the baptism of Vladimir of Kiev in 988, on which occasion he was also married to the Byzantine princess Anna, the sister of the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. However, Christianity is documented to have predated this event in the city of Kiev and in Georgia.

Today the Russian Orthodox Church is the largest of the Orthodox Churches.

Conversion of the Scandinavians

Early evangelisation in

Late Middle Ages (1300–1499)

Hesychast Controversy

- Barlaam of Calabria

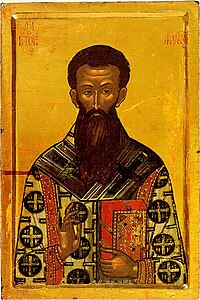

About the year 1337

Barlaam took exception to, as

- Gregory Palamas

On the Hesychast side, the controversy was taken up by St

In these works, St Gregory Palamas uses a distinction, already found in the 4th century in the works of the

validation of God.- Synods

In 1341 the dispute came before a

One of Barlaam's friends,

- Aftermath

Up to this day, the Roman Catholic Church has never fully accepted Hesychasm, especially the distinction between the energies or operations of God and the essence of God, and the notion that those energies or operations of God are uncreated. In Roman Catholic theology as it has developed since the Scholastic period c. 1100–1500, the essence of God can be known, but only in the next life; the grace of God is always created; and the essence of God is pure act, so that there can be no distinction between the energies or operations and the essence of God (see, e.g., the Summa Theologiae of St Thomas Aquinas). Some of these positions depend on Aristotelian metaphysics.

- Views of modern historians

The contemporary historians

Avignon Papacy (1309-1378) and Western Schism (1378-1417)

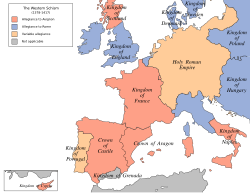

The Western Schism, or Papal Schism, was a prolonged period of crisis in Latin Christendom from 1378 to 1416, when there were two or more claimants to the See of Rome and there was conflict concerning the rightful holder of the papacy. The conflict was political, rather than doctrinal, in nature.

In 1309, Pope Clement V, due to political considerations, moved to Avignon in southern France and exercised his pontificate there. For sixty-nine years popes resided in Avignon rather than Rome. This was not only an obvious source of confusion but of political animosity as the prestige and influence of the city of Rome waned without a resident pontiff. Though Pope Gregory XI, a Frenchman, returned to Rome in 1378, the strife between Italian and French factions intensified, especially following his subsequent death. In 1378 the conclave, elected an Italian from Naples, Pope Urban VI; his intransigence in office soon alienated the French cardinals, who withdrew to a conclave of their own, asserting the previous election was invalid since its decision had been made under the duress of a riotous mob. They elected one of their own, Robert of Geneva, who took the name Pope Clement VII. By 1379, he was back in the palace of popes in Avignon, while Urban VI remained in Rome.

For nearly forty years, there were two papal curias and two sets of cardinals, each electing a new pope for Rome or Avignon when death created a vacancy. Each pope lobbied for support among kings and princes who played them off against each other, changing allegiance according to political advantage. In 1409, a council was convened at Pisa to resolve the issue. The Council of Pisa declared both existing popes to be schismatic (Gregory XII from Rome, Benedict XIII from Avignon) and appointed a new one, Alexander V. But the existing popes refused to resign and thus there were three papal claimants. Another council was convened in 1414, the Council of Constance. In March 1415 the Pisan pope, John XXIII, fled from Constance in disguise; he was brought back a prisoner and deposed in May. The Roman pope, Gregory XII, resigned voluntarily in July. The Avignon pope, Benedict XIII, refused to come to Constance; nor would he consider resignation. The council finally deposed him in July 1417. The council in Constance, having finally cleared the field of popes and antipopes, elected Pope Martin V as pope in November.

Criticism of Church corruption - John Wycliff and Jan Hus

Italian Renaissance

The Renaissance was a period of great cultural change and achievement, marked in Italy by a classical orientation and an increase of wealth through mercantile trade. The city of Rome, the Papacy, and the Papal States were all affected by the Renaissance. On the one hand, it was a time of great artistic patronage and architectural magnificence, where the Church pardoned such artists as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, Fra Angelico, Donatello, and Leonardo da Vinci. On the other hand, wealthy Italian families often secured episcopal offices, including the papacy, for their own members, some of whom were known for immorality, such as Alexander VI and Sixtus IV.

In addition to being the head of the Church, the Pope became one of Italy's most important secular rulers, and pontiffs such as Julius II often waged campaigns to protect and expand their temporal domains. Furthermore, the popes, in a spirit of refined competition with other Italian lords, spent lavishly both on private luxuries but also on public works, repairing or building churches, bridges, and a magnificent system of aqueducts in Rome that still function today. It was during this time that St. Peter's Basilica, perhaps the most recognised Christian church, was built on the site of the old Constantinian basilica. It was also a time of increased contact with Greek culture, opening up new avenues of learning, especially in the fields of philosophy, poetry, classics, rhetoric, and political science, fostering a spirit of humanism—all of which would influence the Church.

Fall of Constantinople (1453)

In 1453, Constantinople fell to the

As a result of the Ottoman conquest and the

Religious rights under the Ottoman Empire

The new Ottoman government that arose from the ashes of Byzantine civilization was neither primitive nor barbaric. Islam not only recognized Jesus as a great prophet, but tolerated Christians as another People of the Book. As such, the Church was not extinguished nor was its canonical and hierarchical organisation significantly disrupted. Its administration continued to function. One of the first things that Mehmet the Conqueror did was to allow the Church to elect a new patriarch, Gennadius Scholarius. The Hagia Sophia and the Parthenon, which had been Christian churches for nearly a millennium were, admittedly, converted into mosques.

However, these rights and privileges (see

See also

- History of Christian theology

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Christianization

- Timeline of Christianity

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Catholic–Protestant relations

Citations

- ^ Davies Europe pp. 291–293

- ^ Woollcombe, K.J. "The Ministry and the Order of the Church in the Works of the Fathers" in The Historic Episcopate. Kenneth M. Carey (Ed.). Dacre Press (1954) p.31f

- ^ R. Gerberding and Jo Anne H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds: An Introduction to European History 300–1492 (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2004), p. 33.

- ^ a b Alick Isaacs (14 June 2015). "Christianity and Islam: Jerusalem in the Middle Ages - 1. Jerusalem in Christianity". The Jewish Agency. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) p. 36

- ^ Joyce 1906, pp. 135–6.

- ^ On the development of penitential practice, see McNeill & Gamer, Medieval Handbooks of Penance, (Columbia University Press, 1938) pp. 9–54

- ^ Mayr-Harting, H. (1991). The coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- ^ Chaney, W. A. (1970). The cult of kingship in Anglo-Saxon England; the transition from paganism to Christianity. Manchester, Eng.: Manchester University Press.

- ^ .

- ^ Epitome, Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754

- ISBN 978-1-107-08544-2.

- ^ "The Great Schism: The Estrangement of Eastern and Western Christendom". orthodoxinfo.com.

- ISBN 978-0-913836-58-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8236-8074-0 Quoting Aleksey Khomyakovpg 87.

- ISBN 0-227-67919-9)

- OCLC 258294189.

- JSTOR 1839922.

- ^ For such an analysis, see Brian Tierney and Sidney Painter, Western Europe in the Middle Ages 300–1475. 6th ed. (McGraw-Hill 1998)

- ^ Rice, Joshua (1 June 2022). "Burn in Hell". History Today. 72 (6): 16–18.[1]

- ^ Murphy, C. (2012). God's Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ISBN 9780810884939.

All the great European universities-Oxford, to Paris, to Cologne, to Prague, to Bologna—were established with close ties to the Church.

- ISBN 9781135205157.

Europe established schools in association with their cathedrals to educate priests, and from these emerged eventually the first universities of Europe, which began forming in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

- ISBN 9789401796361.

- ISBN 9781502606853.

- ISBN 9789059724877.

Many of the medieval universities in Western Europe were born under the aegis of the Catholic Church, usually as cathedral schools or by papal bull as Studia Generali.

- ^ Zlatarski 1972, p. 389

- ^ "Patriarchs of Preslav". Official site of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, p. 208.

- ^ "From Eastern Roman to Byzantine: transformation of Roman culture (500-800)". Indiana University Northwest. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ G. R. Evans, John Wyclif: Myth & Reality (2006)

- ^ Shannon McSheffrey, Lollards of Coventry, 1486–1522 (2003)

- ^ Thomas A. Fudge, Jan Hus: Religious Reform and Social Revolution in Bohemia (2010)

- ^ The Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies[usurped] The New York Times.

- ^ http://www.helleniccomserve.com/pdf/BlkBkPontusPrinceton.pdf [bare URL PDF]

References

- ISBN 0-19-520912-5.

- ISBN 9780521074599.

- Златарски (Zlatarski), Васил (Vasil) (1972) [1927]. История на българската държава през средните векове. Том I. История на Първото българско царство. Част ІІ. (History of the Bulgarian state in the Middle Ages. Volume I. History of the First Bulgarian Empire. Part II) (in Bulgarian) (2nd ed.). София (Sofia): Наука и изкуство (Nauka i izkustvo). OCLC 67080314.

Print resources

- González, Justo L. (1984). The Story of Christianity: Vol. 1: The Early Church to the Reformation. San Francisco: Harper. ISBN 0-06-063315-8.

- Grabar, André (1968). Christian iconography, a study of its origins. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01830-8.

- Guericke, Heinrich Ernst; et al. (1857). A Manual of Church History: Ancient Church History Comprising the First Six Centuries. New York: Wiley and Halsted.

- Hastings, Adrian (1999). A World History of Christianity. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4875-3.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1975). A History of Christianity, Volume 1: Beginnings to 1500 (revised ed.). San Francisco: Harper. ISBN 0-06-064952-6. (paperback).

- Morris, Colin (1972). The discovery of the individual, 1050–1200. London: SPCK. ISBN 0-281-02346-8.

- Morris, Colin (1989). The papal monarchy : the western church from 1050 to 1250. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 0-19-826925-0.

- Morris, Colin (2006). The sepulchre of Christ and the medieval West : from the beginning to 1600. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826928-1.

- Shelley, Bruce L. (1996). Church History in Plain Language (2nd ed.). Word Pub. ISBN 0-8499-3861-9.

Online sources

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas:[usurped] Christianity in History

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas:[usurped] Church as an Institution

- Sketches of Church History From AD 33 to the Reformation by Rev. J. C Robertson, M.A., Canon of CanterburyJoyce, Patrick Weston (1906). A smaller social history of ancient Ireland, treating of the government, military system, and law; religion, learning, and art; trades, industries, and commerce; manners, customs, and domestic life, of the ancient Irish people (PDF). London; New York : Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 21 October 2016.