Prehistoric Europe

| Early Prehistory | |

|---|---|

Germanic tribes, Hallstatt culture | |

Prehistoric Europe refers to Europe before the start of written records,[3] beginning in the Lower Paleolithic. As history progresses, considerable regional unevenness in cultural development emerges and grows. The region of the eastern Mediterranean is, due to its geographic proximity, greatly influenced and inspired by the classical Middle Eastern civilizations, and adopts and develops the earliest systems of communal organization and writing.[4] The Histories of Herodotus (from around 440 BC) is the oldest known European text that seeks to systematically record traditions, public affairs and notable events.[5]

Overview

Widely dispersed, isolated finds of individual fossils of bone fragments (Atapuerca, Mauer mandible), stone artifacts or

Homo sapiens later populated the entire continent during the

The Mesolithic era site Lepenski Vir in modern-day Serbia, the earliest documented sedentary community of Europe with permanent buildings, as well as monumental art, precedes by many centuries sites previously considered to be the oldest known. The community's year-round access to a food surplus prior to the introduction of agriculture was the basis for the sedentary lifestyle.[16] However, the earliest record for the adoption of elements of farming can be found in Starčevo, a community with close cultural ties.[17]

Belovode and

The process of smelting bronze is an imported technology with debated origins and history of geographic cultural profusion. It was established in Europe about 3200 BC in the Aegean and production was centered around Cyprus, the primary source of copper for the Mediterranean for many centuries.[21]

The introduction of metallurgy, which initiated unprecedented technological progress, has also been linked with the establishment of social stratification, the distinction between rich and poor, and use of precious metals as the means to fundamentally control the dynamics of culture and society.[22]

The

During the Iron Age, Central, Western and most of Eastern Europe gradually entered the actual historical period. Greek maritime colonization and Roman terrestrial conquest form the basis for the diffusion of literacy in large areas to this day. This tradition continued in an altered form and context for the most remote regions (

Stone Age

Paleolithic (Old Stone Age)

Oldest fossils, artifacts and sites

Lower and Middle Paleolithic human presence

The climatic record of the Paleolithic is characterised by the Pleistocene pattern of cyclic warmer and colder periods, including eight major cycles and numerous shorter episodes. The northern maximum of human occupation fluctuated in response to the changing conditions, and successful settlement required constant adaption capabilities and problem solving. Most of Scandinavia, the North European Plain and Russia remained off limits for occupation during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic.[29] Populations were low in density and small in number throughout the Palaeolithic.[30]

Associated evidence, such as stone tools, artifacts and settlement localities, is more numerous than fossilised remains of the hominin occupants themselves. The simplest pebble tools with a few flakes struck off to create an edge were found in Dmanisi, Georgia, and in Spain at sites in the Guadix-Baza basin and near Atapuerca. The Oldowan tool discoveries, called Mode 1-type assemblages are gradually replaced by a more complex tradition that included a range of hand axes and flake tools, the Acheulean, Mode 2-type assemblages. Both types of tool sets are attributed to Homo erectus, the earliest and for a very long time the only human in Europe and more likely to be found in the southern part of the continent. However, the Acheulean fossil record also links to the emergence of Homo heidelbergensis, particularly its specific lithic tools and handaxes. The presence of Homo heidelbergensis is documented since 600,000 BC in numerous sites in Germany, Great Britain and northern France.[31]

Although palaeoanthropologists generally agree that Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis immigrated to Europe, debates remain about migration routes and the chronology.[32]

The fact that The Neanderthal fossil record ranges from Western Europe to the

Upper Paleolithic

Homo sapiens arrived in Europe around 45,000 and 43,000 years ago via the Levant and entered the continent through the Danubian corridor, as the fossils at Peștera cu Oase suggest.[40] The fossils' genetic structure indicates a recent Neanderthal ancestry and the discovery of a fragment of a skull in Israel in 2008 support the notion that humans interbred with Neanderthals in the Levant.[citation needed]

After the slow processes of the previous hundreds of thousands of years, a turbulent period of Neanderthal–Homo sapiens coexistence demonstrated that cultural evolution had replaced biological evolution as the primary force of adaptation and change in human societies.[41][42]

Generally small and widely dispersed fossil sites suggest that Neanderthals lived in less numerous and more socially isolated groups than Homo sapiens. Tools and Levallois points are remarkably sophisticated from the outset, but they have a slow rate of variability, and general technological inertia is noticeable during the entire fossil period. Artifacts are of utilitarian nature, and symbolic behavioral traits are undocumented before the arrival of modern humans. The Aurignacian culture, introduced by modern humans, is characterized by cut bone or antler points, fine flint blades and bladelets struck from prepared cores, rather than using crude flakes. The oldest examples and subsequent widespread tradition of prehistoric art originate from the Aurignacian.[43][44][45][46]

After more than 100,000 years of uniformity, around 45,000 years ago, the Neanderthal fossil record changed abruptly. The Mousterian had quickly become more versatile and was named the

Around 32,000 years ago, the

The Solutrean culture, extended from northern Spain to southeastern France, includes not only a

Around 19,000 BC, Europe witnesses the appearance of a new culture, known as

With the Magdalenian culture, the Paleolithic development in Europe reaches its peak and this is reflected in art, owing to previous traditions of paintings and sculpture.

Around 12,500 BC, the Würm Glacial Age ended. Slowly, through the following millennia, temperatures and sea levels rose, changing the environment of prehistoric people. Ireland and Great Britain became islands, and Scandinavia became separated from the main part of the European Peninsula. (They had all once been connected by a now-submerged region of the continental shelf known as Doggerland.) Nevertheless, the Magdalenian culture persisted until 10,000 BC, when it quickly evolved into two microlith cultures: Azilian, in Spain and southern France, and Sauveterrian, in northern France and Central Europe. Despite some differences, both cultures shared several traits: the creation of very small stone tools called microliths and the scarcity of figurative art, which seems to have vanished almost completely, which was replaced by abstract decoration of tools.[50]

In the late phase of the epi-Paleolithic period, the Sauveterrean culture evolved into the so-called

-

Bone flute, Aurignacian, Geissenklösterlecave, 43,000 BC

-

Adorant from the Geißenklösterle cave, Aurignacian, 42,000 to 40,000 BC

-

Lion-man, Aurignacian, c. 41,000 to 35,000 BC

-

Aurignacian cave paintings, Chauvet Cave, c. 30,000 BC

-

Venus of Dolní Věstonice, Gravettian, c. 29,000 BC

-

Venus of Laussel, Gravettian, c. 23,000 BC

-

Venus of Brassempouy, c. 23,000 BC

-

Antler carving, Magdalenian, 15,000 BC

Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age)

A transition period in the development of human technology between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic, the

In areas with limited glacial impact, the term "Epipaleolithic" is sometimes preferred for the period. Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the Last Glacial Period ended had a much more apparent Mesolithic era that lasted millennia. In Northern Europe, societies were able to live well on rich food supplies from the marshlands, which had been created by the warmer climate. Such conditions produced distinctive human behaviours that are preserved in the material record, such as the Maglemosian and Azilian cultures. Such conditions delayed the coming of the Neolithic to as late as 5,500 years ago in Northern Europe.

As what

-

Venus of Monruz, Switzerland, c. 9000 BC

-

Shigir Idol, Russia, c. 10,000 BC

-

Roca dels Moros, Spain

-

Pesse canoe, Netherlands, c. 8000 BC

-

Elk's Head of Huittinen, Finland, c. 6500 BC

-

Holmegaard bow (replica), Denmark, 7000 BC

-

Lepenski Vir stone sculpture, Serbia, c. 7000 BC

Neolithic (New Stone Age)

The European

Early Neolithic

Apparently related with the Anatolian culture of

Middle Neolithic

This phase, starting 7000 years ago was marked by the consolidation of the Neolithic expansion towards western and northern Europe but also by the rise of new cultures in the Balkans, notably the

Late Neolithic

This period occupied the first half of the 6th millennium BC. The tendencies of the previous period consolidated and so there was a fully-formed Neolithic Europe, with five main cultural regions:

- Danubian cultures: from northern France to western Ukraine. Now split into several local cultures, the most relevant ones being the Romanian branch (Rössen culture that was pre-eminent in the west, and the Lengyel cultureof Austria and western Hungary, which would have a major role in later periods.

- Mediterranean cultures: from the Adriatic to eastern Spain, including Italy and large portions of France and Switzerland. They were also diversified into several groups.

- The area of Dimini-Vinca: Thessaly, Macedonia and Serbia but extending its influence to parts of the mid-Danubian basin (Tisza, Slavonia) and southern Italy.

- Eastern Europe: basically central and eastern Ukraine and parts of southern Russia and Belarus (Dniepr-Don culture). This area has the earliest evidence for domesticated horses.

- Atlantic Europe: a mosaic of local cultures, some of them still pre-Neolithic, from Portugal to southern Sweden. In around 5800 BC, western France began to incorporate the Megalithic style of burial.

-

Sesklo culture, Greece, c. 6000-5300 BC

-

Dimini, walled acropolis, Greece, c. 4800 BC

-

Karanovo culture, Bulgaria, 6th mill. BC

-

Karanovo culture, Bulgaria, 5th mill. BC

-

Vinča culturefigurine, Serbia, c. 5000 BC

-

Linear Pottery culture, Germany, 5000 BC

-

Goseck Circle, Germany, 4900 BC

-

France, 4000 BC

-

Locmariaquer megaliths, France, 4500 BC

-

Monte d'Accoddi, Sardinia, c. 3500-3000 BC.[54]

-

Spain, c. 3700 BC

-

Hungary, 5300 BC[55]

-

Bonu Ighinu culture, Sardinia, 4500 BC

-

Okolište, Bosnia and Herzegovina, c. 5000 BC

Chalcolithic (Copper Age)

Also known as "Copper Age", the European Chalcolithic was a time of significant changes, the first of which was the invention of copper metallurgy. This is first attested in the Vinca culture in the 6th millennium BC. The Balkans became a major centre for copper extraction and metallurgical production in the 5th millennium BC. Copper artefacts were traded across the region, eventually reaching eastwards across the steppes of eastern Europe as far as the Khavalynsk culture. The 5th millennium BC also saw the appearance of economic stratification and the rise of ruling elites in the Balkan region, most notably in the Varna culture (c. 4500 BC) in Bulgaria, which developed the first known gold metallurgy in the world.

The economy of the Chalcolithic was no longer that of peasant communities and tribes, since some materials began to be produced in specific locations and distributed to wide regions. Mining of metal and stone was particularly developed in some areas, along with the processing of those materials into valuable goods.[56]

Early Chalcolithic, 5500-4000 BC

From 5500 BC onwards, Eastern Europe was apparently infiltrated by people originating from beyond the Volga, creating a plural complex known as Sredny Stog culture, which substituted the previous Dnieper-Donets culture in Ukraine, pushing the natives to migrate northwest to the Baltic and to Denmark, where they mixed with the natives (TRBK A and C). The emergence of the Sredny Stog culture may be correlated with the expansion of Indo-European languages, according to the Kurgan hypothesis. Near the end of the period, around 4000 BC, another westward migration of supposed Indo-European speakers left many traces in the lower Danube area (culture of Cernavodă I) in what seems to have been an invasion.[57]

Meanwhile, the Danubian Lengyel culture absorbed its northern neighbours in the Czech Republic and Poland for some centuries, only to recede in the second half of the period. The hierarchical model of the Varna culture seems to have been replicated later in the Tiszan region with the Bodrogkeresztur culture. Labour specialisation, economic stratification and possibly the risk of invasion may have been the reasons behind this development.

In the western Danubian region (the Rhine and Seine basins), the Michelsberg culture displaced its predecessor, the Rössen culture. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean basin, several cultures (most notably the Chasséen culture in southeastern France and the Lagozza culture in northern Italy) converged into a functional union of which the most significant characteristic was the distribution network of honey-coloured silex. Despite the unity, the signs of conflicts are clear, as many skeletons show violent injuries. This was the time and area of Ötzi, the famous man found in the Alps.

- Middle Chalcolithic, 4000-3000 BC

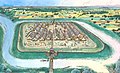

This period extends through the first half of the 4th millennium BC. During this period the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture in Ukraine experienced a massive expansion, building the largest settlements in the world at the time, described as the first cities in the world by some scholars. The earliest known evidence for wheeled vehicles, in the form of wheeled models, also comes from Cucuteni-Trypillia sites, dated to c. 3900 BC.

In the Danubian region the powerful Baden culture emerged circa 3500 BC, extending more or less across the region of Austria-Hungary. The rest of the Balkans was profoundly restructured after the invasions of the previous period, with the Coțofeni culture in the central Balkans showing pronounced eastern (or presumably Indo-European) traits. The new Ezero culture in Bulgaria (3300 BC), shows the first evidence of pseudo-bronze (or arsenical bronze), as does the Baden culture and the Cycladic culture (in the Aegean) after 2800 BC.[58]

In Eastern Europe, the

Large towns with stone walls appeared in two different areas of the Iberian Peninsula: one in the Portuguese region of

-

Varna culture, Bulgaria, 4500 BC

-

Cucuteni-Trypilliapottery, Ukraine

-

Maidanetske, Ukraine, c. 3800 BC

-

Bodrogkeresztúr culture, Hungary, 4000-3600 BC

-

Ħal Saflieni figurine, Malta, 3300–3000 BC

-

Dimini culture, Greece, c. 4000 BC

-

Baden culture, Hungary, 3300 BC

-

Funnelbeaker culture, Denmark, 3200 BC

-

Ljubljana Wheel, Slovenia, 3150 BC

-

Los Millares, Spain, c. 3100 BC

-

Yamnaya stone stele, Ukraine, c. 2600 BC

-

Bell Beaker culture burial, Spain, c. 2500 BC

-

Stonehenge, Britain, 2500 BC

-

Silbury Hill, Britain, c. 2400 BC

-

Gold lunula, Ireland, c. 2400 BC

Bronze Age

Use of Bronze begins in the

The rest of Europe remained mostly unchanged and apparently peaceful. In 2300 BC, the first Beaker Pottery appeared in Bohemia and expanded in many directions but particularly westward, along the Rhone and the seas, reaching the culture of Vila Nova (Portugal) and Catalonia (Spain) as their limits. Simultaneously but unrelatedly, in 2200 BC in the Aegean region, the

The second phase of Beaker Pottery, from 2100 BC onwards, is marked by the displacement of the centre of the phenomenon to Portugal, within the culture of Vila Nova. The new centre's influence reached to all of southern and western France but was absent in southern and western Iberia, with the notable exception of Los Millares. After 1900 BC, the centre of the Beaker Pottery returned to Bohemia, and in Iberia, a decentralisation of the phenomenon occurred, with centres in Portugal but also in Los Millares and Ciempozuelos. According to radiocarbon dating, the Early Bronze Age began on the Northern Iberian Plateau in 2100 cal. BC and Late Bronze Age in 1350 cal. BC.[8][9][10]

Though the use of bronze started much earlier in the Aegean area (c. 3.200 BC), c. 2300 BC can be considered typical for the start of the Bronze Age in Europe in general.

- c. 2300 BC, the Central European cultures of started working bronze, a technique that reached them through the Balkans and Danube.

- c. 1800 BC, the culture of Los Millares, in Southwestern Spain, was substituted by that of El Argar, fully of the Bronze Age, which may well have been a centralised state.

- c. 1700 BC is considered a reasonable date to place the start of Mycenaean Greece, after centuries of infiltration of Indo-European Greeks of an unknown origin.

- c. 1600 BC, most of these Central European cultures were unified in the powerful Mycenaean Greeks.

- Around 1300 BC, the Indo-European cultures of Central Europe, such as ), northeastern Italy, parts of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, northeastern Spain and southwestern England.

Derivations of the sudden expansion were the

Simultaneously, around then, the culture of

-

Mycenaean diadem, Greece, c. 1600 BC

-

Treasury of Atreus, Greece, c. 1300 BC

-

Bush Barrow, Britain, 1900 BC

-

Trundholm Sun Chariot, Denmark, 1500 BC

-

Argaric culture gold diadem, Spain, 1600 BC

-

Nuraghe, Sardinia, c. 1600 BC

-

Nuragic ship model, Sardinia, 1000 BC

-

Sintashta culture chariot, Russia, c. 2000 BC

-

Terramare culture, Italy, 1650–1150 BC

-

Switzerland, 1000 BC

-

Berlin Gold Hat, Germany, c. 1000 BC

-

Bronze cuirasses, France, c. 900 BC

-

Urnfield culture, Germany, c. 1100 BC

-

Bronze chariot wheel, Romania, c. 13th century BC

Iron Age

Though the use of iron was known to the Aegean peoples about 1100 BC, it failed to reach Central Europe before 800 BC, when it gave way to the Hallstatt culture, an Iron Age evolution of the Urnfield culture. Around then, the

Nevertheless, from the 7th century BC onwards, the Greeks recovered their power and started their own colonial expansion, founding Massalia (modern

The second phase of the European Iron Age was defined particularly by the Celtic

The decline of Celtic power under the expansive pressure of

-

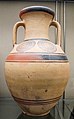

Protogeometric amphora, Greece, c. 975–950 BC

-

Villanovan culture warrior burial, Italy, 730 BC

-

Hallstatt culture armour, Austria, 7th century BC

-

Celtic Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave, Germany, 530 BC

-

Vix palace, Hallstatt culture, France, 500 BC

-

Battersea Shield, Britain, c.350–50 BC

-

Gold torc, Britain, 70 BC

-

Scythian gold pectoral, Ukraine, 4th century BC

-

Geto-Dacian gold helmet, Romania, c. 400 BC

-

Denmark, 1st century BC

-

Lady of Elche, Spain, 4th century BC

-

Thracian tomb, Bulgaria, 3rd century BC

-

Broch of Mousa, Scotland, c. 300-100 BC

-

Broighter gold boat, Ireland, c. 100 BC

-

Chariot fitting, La Tène culture, France

Genetic history

The genetic history of Europe has been inferred by observing the patterns of genetic diversity across the continent and in the surrounding areas. Use has been made of both classical genetics and molecular genetics.[62][63] Analysis of the DNA of the modern population of Europe has mainly been used but use has also been made of ancient DNA.

This analysis has shown that modern man entered Europe from the Near East before the Last Glacial Maximum but retreated to refuges in southern Europe in this cold period. Subsequently, people spread out over the whole continent, with subsequent limited migration from the Near East and Asia.[64]

According to a study in 2017, the early farmers belonged predominantly to the paternal Haplogroup G-M201.[65] The maternal haplogroup N1a was also frequent in the farmers.[66]

Evidence from genome analysis of ancient human remains suggests that the modern native populations of Europe largely descend from three distinct lineages: Mesolithic

Linguistic history

The written linguistic record in Europe first begins with the Mycenaean record of early Greek in the Late Bronze Age. Unattested languages spoken in Europe in the Bronze and Iron Ages are the object of reconstruction in

Indo-European is assumed to have spread from the

Various pre-Indo-European substrates have been postulated, but remain speculative; the "

Donald Ringe emphasizes the "great linguistic diversity" which would generally have been predominant in any area inhabited by small-scale, tribal pre-state societies.[76]

See also

- Archaeological sites sorted by continent and age

- Atlantic Europe

- European megalithic culture

- Mediterranean Europe

- Prehistoric Britain

- Prehistoric Cyprus

- Prehistoric France

- Prehistoric Georgia

- Prehistoric Hungary

- Prehistoric Iberia

- Prehistoric Ireland

- Prehistoric Italy

- Prehistoric Romania

- Prehistoric Scotland

- Prehistoric Transylvania

- Prehistory of Brittany

- Prehistory of Poland (until 966)

References

- ^ "Oldest Human Fossil in Western Europe Found in Spain". Popular-archaeology. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- S2CID 4401629.

- ^ "Prehistory – definition of prehistory in English". oxford dictionaries. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ "Ancient Scripts: Linear A". Ancientscripts.com. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Herodotus – Ancient History". History com. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Atapuerca". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ "Fossils Reveal Clues on Human Ancestor". The New York Times. 20 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Marcos Saiz (2006), pp. 225–270.

- ^ a b c d e f Marcos Saiz (2016), pp. 686–696.

- ^ a b c d e f Marcos Saiz & Díez (2017), pp. 45–67.

- .

- ^ a b "Neanderthal Anthropology". Encyclopædia Britannica. January 29, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

...Neanderthals inhabited Eurasia from the Atlantic regions…

- ^ "Neanderthals' Last Stand Is Traced". The New York Times. September 13, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". The New York Times. 2 November 2011.

- ^ "DNA Deciphers Roots of Modern Europeans". The New York Times. June 10, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Rusu, Aurelian I. "Lepenski Vir – Schela Cladovei culture's chronology and its interpretation". Brukenthal. Acta Musei. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Archaeological Exhibitions". Duncancaldwell. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers". UCL Institute of Archaeology. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Early metallurgy: copper smelting, Belovode, Serbia: Vinča culture". quantumfuturegroup.org. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "The oldest Copper Metallurgy in the Balkans" (PDF). Penn Museum. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "HISTORY OF METALLURGY". HistoryWorld.net. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- S2CID 145631324. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Hittites: Civilization, History & Definition" (Video & Lesson Transcript). Study.com. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0313391811.

- ^ "Lithic Assemblage Dated to 1.57 Million Years Found at Lézignan-la-Cébe, Southern France". Anthropology.net. 2009-12-17. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ "Creationist Arguments: Orce Man". Talkorigins. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- PMID 21531443.

- ^ Arlette P. Kouwenhoven (May–June 1997). "World's Oldest Spears". Archaeology. 50 (3). Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ "Paleolithic settlement". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ISBN 9781108710060.

- PMID 24278105.

- ^ "Early Human Evolution: Homo ergaster and erectus". palomar edu. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Cookson, Clive (June 27, 2014). "Palaeontology: How Neanderthals evolved". Financial Times. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- S2CID 88427585.

- ^ "Oldest Ancient-Human DNA Details Dawn of Neandertals". Scientific American. March 14, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "Homo heidelbergensis". Smithsonian Institution. 2010-02-14. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

Comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests that the two lineages diverged from a common ancestor, most likely Homo heidelbergensis

- ^ Edwards, Owen (March 2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-631-17423-3. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis". Smithsonian Institution. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

...The Mousterian stone tool industry of Neanderthals is characterized by…

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (2 Nov 2011). "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ "Chapter 5: Hunting & Gathering Societies". Florida International University. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ "Creativity in human evolution and prehistory" (PDF). Arizona University. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- S2CID 85316570.

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis Brief Summary". EOL. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- PMID 25020018.

- ISBN 978-1-4419-6633-9. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

One of the earliest dates for an Aurignacian assemblage is greater than 43,000 BC from Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria ...

- ^ "Chatelperronian Transition to Upper Paleolithic". About.com. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- PMID 21698105.

- ^ Carpenter, Jennifer (20 June 2011). "Early human fossils unearthed in Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Mas d'Azil". Logan Museum. Beloit College. Archived from the original on 30 April 2001.

- ^ "The Thaïs Bone, France". UNESCO Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy.

The engraving on the Thaïs bone is a non-decorative notational system of considerable complexity. The cumulative nature of the markings together with their numerical arrangement and various other characteristics strongly suggest that the notational sequence on the main face represents a non-arithmetical record of day-by-day lunar and solar observations undertaken over a time period of as much as 3½ years. The markings appear to record the changing appearance of the moon, and in particular its crescent phases and times of invisibility, and the shape of the overall pattern suggests that the sequence was kept in step with the seasons by observations of the solstices. The latter implies that people in the Azilian period were not only aware of the changing appearance of the moon but also of the changing position of the sun, and capable of synchronizing the two. The markings on the Thaïs bone represent the most complex and elaborate time-factored sequence currently known within the corpus of Palaeolithic mobile art. The artefact demonstrates the existence, within Upper Palaeolithic (Azilian) cultures c. 12,000 years ago, of a system of time reckoning based upon observations of the phase cycle of the moon, with the inclusion of a seasonal time factor provided by observations of the solar solstices.

- ^ Childe 1925

- ^ The supposed autochthony of Hittites, the Indo-Hittite hypothesis and the migration of agricultural "Indo-European" societies were intrinsically linked by Colin Renfrew 2001

- doi:10.4312/dp.38.16.

- ^ "Ritual and Memory: Neolithic Era and Copper Age". Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. 2022.

- ^ "The Copper Age in northern Italy". University of Arizona Libraries. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Harvey B. Re-Examining Late Chalcolithic Cultural Collapse in South-East Europe (MA Thesis). University of Arkansas. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-3110146516.

- ^ "Alternative Linguiatics – Ethnicity of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures of Eastern Europe". Alterling ucoz de. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- S2CID 163672997.

- ^ "Steppe migrant thugs pacified by Stone Age farming women". ScienceDaily. Faculty of Science - University of Copenhagen. 4 April 2017.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994

- ^ Metspalu et al. 2004

- ^ Achilli et al. 2004

- PMID 29144465.

- ^ Crabtree & Bogucki 2017, p. 55

- ^ "When the First Farmers Arrived in Europe, Inequality Evolved". Scientific American. 1 July 2020.

- PMID 29144465.

- ISBN 978-1-934536-90-2.p.55: "In addition, uniparental markers changed suddenly as mtDNA N1a and Y haplogroup G2a, which had been very common in the EEF agricultural population, were replaced by Y haplogroups R1a and R1b and by a variety of mtDNA haplogroups typical of the Steppe Yamnaya population. The uniparental markers show that the migrants included both men and women from the steppes."

- PMID 31729399. ""The subsequent spread of Yamnaya-related people and Corded Ware Culture in the late Neolithic and Bronze Age were accompanied with the increase of haplogroups I, U2 and T1 in Europe (See8 and references therein)."

- PMID 30072694.

- ^ Kristian Kristiansen, Morten E. Allentoft, Karin M. Frei, Rune Iversen, Niels N. Johannsen, Guus Kroonen, Łukasz Pospieszny, T. Douglas Price, Simon Rasmussen, Karl-Göran Sjögren, Martin Sikora, Eske Willerslev. Re-theorising mobility and the formation of culture and language among the Corded Ware Culture in Europe. Antiquity, Volume 91, Issue 356, April 2017, pp. 334 - 347.

- ^ Vennemann 2003

- ^ Wiik 2002.

- ^ Adams and Otte 1999

- ^ Ringe, Don (January 6, 2009). "The Linguistic Diversity of Aboriginal Europe". Language Log. Mark Liberman. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

Sources

- Achilli, Alessandro; Rengo, Chaira; Magri, Chiara; Battaglia, Vincenza; Olivieri, Anna; Scozari, Rosaria; Cruciani, Fulvio; Zeviani, Massimo; Briem, Egill; Carelli, Valerio; Moral, Pedro; Dugoujon, Jean-Michel; Roostalu, Urmas; Loogväli, Eva-Liss; Kivisild, Toomas; Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Richards, Martin; Villems, Richard; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. Silvana; Semino, Ornella; Torroni, Antonio (2004). "The Molecular Dissection of mtDNA Haplogroup H Confirms that the Franco-Cantabrian Glacial Refuge was a Major Source for the European Gene Pool". American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (5): 910–918. PMID 15382008.

- Adams, Jonathan; Otte, Marcel (1999). "Did Indo-European Languages Spread Before Farming?". Current Anthropology. 40 (1): 73–77. S2CID 143134729.

- Childe, V. Gordon. 1925. The Dawn of European Civilization. New York: Knopf.

- Childe V.Gordon. 1950. Prehistoric Migrations in Europe. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Cavalli-Sforza L.L., Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Finnilä, Saara; Lehtonen, Mervi S.; Majamaa, Kari (2001). "Phylogenetic Network for European mtDNA". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (6): 1475–1484. PMID 11349229.

- Gimbutas, M (1980). "The Kurgan wave migration (c. 3400–3200 B.C.) into Europe and the following transformation of culture". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 8: 273–315.

- Marcos Saiz, F. Javier (2006). La Sierra de Atapuerca y el Valle del Arlanzón. Patrones de asentamiento prehistóricos. Editorial Dossoles. Burgos, Spain. ISBN 9788496606289.

- Marcos Saiz, F. Javier (2016). La Prehistoria Reciente del entorno de la Sierra de Atapuerca (Burgos, España). British Archaeological Reports (Oxford, U.K.), BAR International Series 2798. ISBN 9781407315195.

- Marcos Saiz, F.J.; Díez, J.C. (2017). "The Holocene archaeological research around Sierra de Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain) and its projection in a GIS geospatial database". Quaternary International. 433 (A): 45–67. .

- Macaulay, Vincent; Richards, Martin; Hickey, Eileen; Vega, Emilce; Cruciani, Fulvio; Guida, Valentina; Scozzari, Rosaria; Bonné-Tamir, Batsheva; Sykes, Bryan; Torroni, Antonio (1999). "The Emerging Tree of West Eurasian mtDNAs: A Synthesis of Control-Region Sequences and RFLPs". American Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (1): 232–249. PMID 9915963.

- Metspalu, Mait, Toomas Kivisild, Ene Metspalu, Jüri Parik, Georgi Hudjashov, Katrin Kaldma, Piia Serk, Monika Karmin, Doron M Behar, M Thomas P Gilbert, Phillip Endicott, Sarabjit Mastana, Surinder S Papiha, Karl Skorecki, Antonio Torroni and Richard Villems. 2004. "Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in South and Southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans." BMC Genetics 5

- Piccolo, Salvatore. 2013. Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily. Abingdon (GB): Brazen Head Publishing.

- Renfrew, Colin. 2001. "The Anatolian origins of Proto-Indo-European and the autochthony of the Hittites." In Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language Family, R. Drews ed., pp. 36–63. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man.

- Venemann, Theo. 2003. Europa Vasconica, Europa Semitica. Trends in Linguistic Studies and Monographs No. 138. New York and Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Wiik, Kalevi. 2002. Europpalaisten Juuret. Athens: Juvaskylä

External links

![]() Media related to Prehistory of Europe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prehistory of Europe at Wikimedia Commons

- Europe's oldest prehistoric town unearthed in Bulgaria

- [Hans Slomp (2011). Europe, a Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0-313-39181-1. Europe, a Political Profile]

- Neolithic and Chalcolithic Artifacts from the Balkans

- Central European Neolithic Chronology

- South East Europe pre-history summary to 700 BC

- Prehistoric art of the Pyrenees

Paleolithic sanctuaries:

![Monte d'Accoddi, Sardinia, c. 3500-3000 BC.[54]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/Monte_d%27Accoddi%2C_reconstruction_1.jpg/120px-Monte_d%27Accoddi%2C_reconstruction_1.jpg)

![Tisza culture, Hungary, 5300 BC[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/Tisza1.jpg/120px-Tisza1.jpg)