Trade union: Difference between revisions

9,784 edits Some wiki links and minor typo fixes |

9,784 edits Boldly remove list of trade unions by country, for being woefully incomplete and poorly cited. Better to link to List of trade unions and try give a comprehensive summary instead of cherrypicking a dozen countries that are each incomplete in their own respect. |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

=== Health === |

=== Health === |

||

In the United States, higher union density has been associated with lower suicide/overdose deaths.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Eisenberg‐Guyot|first1=Jerzy|last2=Mooney|first2=Stephen J.|last3=Hagopian|first3=Amy|last4=Barrington|first4=Wendy E.|last5=Hajat|first5=Anjum|date=2020|title=Solidarity and disparity: Declining labor union density and changing racial and educational mortality inequities in the United States|url= |journal=American Journal of Industrial Medicine|language=en|volume=63|issue=3|pages=218–231|doi=10.1002/ajim.23081|issn=1097-0274|pmc=7293351|pmid=31845387| quote=Results – Overall, a 10% increase in union density was associated with a 17% relative decrease in overdose/suicide mortality (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70, 0.98), or 5.7 lives saved per 100 000 person‐years (95% CI: −10.7, −0.7). Union density's absolute (lives‐saved) effects on overdose/suicide mortality were stronger for men than women, but its relative effects were similar across genders. Union density had little effect on all‐cause mortality overall or across subgroups, and modeling suggested union‐density increases would not affect mortality inequities. Conclusions - Declining union density (as operationalized in this study) may not explain all‐cause mortality inequities, although increases in union density may reduce overdose/suicide mortality. }}</ref> Decreased unionisation rates in the United States have been linked to an increase in occupational fatalities.<ref name="Zoorob 2018">{{cite journal | last=Zoorob | first=Michael | title=Does 'right to work' imperil the right to health? The effect of labour unions on workplace fatalities | journal=Occupational and Environmental Medicine | volume=75 | issue=10 | date=October 1, 2018 | issn=1351-0711 | pmid=29898957 | doi=10.1136/oemed-2017-104747 | pages=736–738 | s2cid=49187014 | url=https://oem.bmj.com/content/75/10/736 | access-date=January 31, 2022 |quote= The Local Average Treatment Effect of a 1% decline in unionisation attributable to RTW is about a 5% increase in the rate of occupational fatalities. In total, RTW laws have led to a 14.2% increase in occupational mortality through decreased unionisation.}}</ref> |

In the United States, higher union density has been associated with lower suicide/overdose deaths.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Eisenberg‐Guyot|first1=Jerzy|last2=Mooney|first2=Stephen J.|last3=Hagopian|first3=Amy|last4=Barrington|first4=Wendy E.|last5=Hajat|first5=Anjum|date=2020|title=Solidarity and disparity: Declining labor union density and changing racial and educational mortality inequities in the United States|url= |journal=American Journal of Industrial Medicine|language=en|volume=63|issue=3|pages=218–231|doi=10.1002/ajim.23081|issn=1097-0274|pmc=7293351|pmid=31845387| quote=Results – Overall, a 10% increase in union density was associated with a 17% relative decrease in overdose/suicide mortality (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70, 0.98), or 5.7 lives saved per 100 000 person‐years (95% CI: −10.7, −0.7). Union density's absolute (lives‐saved) effects on overdose/suicide mortality were stronger for men than women, but its relative effects were similar across genders. Union density had little effect on all‐cause mortality overall or across subgroups, and modeling suggested union‐density increases would not affect mortality inequities. Conclusions - Declining union density (as operationalized in this study) may not explain all‐cause mortality inequities, although increases in union density may reduce overdose/suicide mortality. }}</ref> Decreased unionisation rates in the United States have been linked to an increase in occupational fatalities.<ref name="Zoorob 2018">{{cite journal | last=Zoorob | first=Michael | title=Does 'right to work' imperil the right to health? The effect of labour unions on workplace fatalities | journal=Occupational and Environmental Medicine | volume=75 | issue=10 | date=October 1, 2018 | issn=1351-0711 | pmid=29898957 | doi=10.1136/oemed-2017-104747 | pages=736–738 | s2cid=49187014 | url=https://oem.bmj.com/content/75/10/736 | access-date=January 31, 2022 |quote= The Local Average Treatment Effect of a 1% decline in unionisation attributable to RTW is about a 5% increase in the rate of occupational fatalities. In total, RTW laws have led to a 14.2% increase in occupational mortality through decreased unionisation.}}</ref> |

||

==Trade unions by country== |

|||

{{Cleanup reorganize|date=January 2023|reason=This section should only be a rough summary of trade union's regional differences, not a complete listing for every country|section}} |

|||

===Australia=== |

|||

{{Main|List of trade unions in Australia}} |

|||

The [[Australian labour movement]] generally sought to end [[child labour]] practices, improve [[worker safety]], increase wages for both union workers and non-union workers, raise the entire society's [[standard of living]], reduce the hours in a work week, provide public education for children, and bring other benefits to [[working class]] families.<ref>[http://actu.com.au/AboutACTU/HistoryoftheACTU/default.aspx History of the ACTU.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081121190936/http://www.actu.com.au/AboutACTU/HistoryoftheACTU/default.aspx |date=21 November 2008 }} Australian Council of Trade Unions.</ref> |

|||

[[Melbourne Trades Hall]] was opened in 1859 with [[Labour council|Trades and Labour Councils]] and [[Trades Hall]]s opening in all cities and most regional towns in the next forty years. During the 1880s [[Trade unions]] developed among [[Sheep shearer|shearers]], [[miner]]s, and [[stevedore]]s (wharf workers), but soon spread to cover almost all [[blue-collar]] jobs. Shortages of labour led to high wages for a prosperous skilled working class, whose unions demanded and got an [[eight-hour day]] and other benefits unheard of in Europe. |

|||

[[File:Melbourne eight hour day march-c1900.jpg|thumb|right|[[Eight-hour day]] march circa 1900, outside Parliament House in Spring Street, [[Melbourne]]]] |

|||

Australia gained a reputation as "the working man's paradise". Some employers tried to undercut the unions by importing Chinese labour. This produced a reaction which led to all the colonies restricting Chinese and other Asian immigration. This was the foundation of the [[White Australia Policy]]. The "Australian compact", based around centralised industrial arbitration, a degree of government assistance particularly for primary industries, and White Australia, was to continue for many years before gradually dissolving in the second half of the 20th century. |

|||

In the 1870s and 1880s, the growing [[Australian labour movement|trade union]] movement began a series of protests against foreign labour. Their arguments were that Asians and Chinese took jobs away from white men, worked for "substandard" wages, lowered working conditions and refused unionisation.<ref name="Markey">{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.highbeam.com/library/docfree.asp?DOCID=1G1:18167215&ctrlInfo=Round20%3AMode20c%3ADocG%3AResult&ao= |

|||

|archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20171019161339/https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-18167215.html |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

|archive-date=19 October 2017 |

|||

|last =Markey |

|||

|first =Raymond |

|||

|date=1 January 1996 |

|||

|title=Race and Organized Labor in Australia, 1850–1901 |

|||

|publisher =The Historian |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Objections to these arguments came largely from wealthy land owners in rural areas.<ref name="Markey"/> It was argued that without Asiatics to work in the tropical areas of the [[Northern Territory]] and Queensland, the area would have to be abandoned.<ref name="Griffiths">{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.philgriffiths.id.au/writings/articles/Shadow%20of%20mill.rtf |

|||

|last =Griffiths |

|||

|first =Phil |

|||

|date=4 July 2002 |

|||

|title=Towards White Australia: The shadow of Mill and the spectre of slavery in the 1880s debates on Chinese immigration |

|||

|format =RTF |

|||

|publisher=11th Biennial National Conference of the Australian Historical Association |

|||

|access-date =14 June 2006 |

|||

}}</ref> Despite these objections to restricting immigration, between 1875 and 1888 all Australian colonies enacted legislation which excluded all further Chinese immigration.<ref name="Griffiths" /> Asian immigrants already residing in the Australian colonies were not expelled and retained the same rights as their Anglo and Southern compatriots. |

|||

The [[Barton Government]] which came to power after the first elections to the Commonwealth parliament in 1901 was formed by the [[Protectionist Party]] with the support of the [[Australian Labor Party]]. The support of the Labor Party was contingent upon restricting non-white immigration, reflecting the attitudes of the [[Australian Workers Union]] and other labour organisations at the time, upon whose support the Labor Party was founded. |

|||

===Canada=== |

|||

{{main|List of trade unions in Canada}} |

|||

Canada's first trade union, the Labourers' Benevolent Association (now International Longshoremen's Association Local 273), formed in [[Saint John, New Brunswick]] in 1849. The union was formed when Saint John's longshoremen banded together to lobby for regular pay and a shorter workday.<ref>{{cite web|title=For Whom The Bells Toll|url=http://www.wfhathewaylabourexhibitcentre.ca/labour-history/for-whom-the-bells-toll/|publisher=Hatheway Labour Exhibit Center|access-date=May 6, 2017}}</ref> Canadian unionism had early ties with [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|Britain]] and Ireland. Tradesmen who came from Britain brought traditions of the British trade union movement, and many British unions had branches in Canada. Canadian unionism's ties with the United States eventually replaced those with Britain. |

|||

Collective bargaining was first recognized in 1945, after the strike by the [[United Auto Workers]] at the [[General Motors]]' plant in [[Oshawa, Ontario]]. |

|||

Justice [[Ivan Rand]] issued a landmark legal decision after the strike in [[Windsor, Ontario]], involving 17,000 [[Ford Motor Company|Ford]] workers. He granted the union the compulsory check-off of union dues. Rand ruled that all workers in a bargaining unit benefit from a union-negotiated contract. Therefore, he reasoned they must pay union dues, although they do not have to join the union. |

|||

The post-[[World War II]] era also saw an increased pattern of unionization in the public service. Teachers, nurses, social workers, professors and cultural workers (those employed in museums, orchestras and art galleries) all sought private-sector collective bargaining rights. The [[Canadian Labour Congress]] was founded in 1956 as the [[national trade union center]] for Canada. |

|||

In the 1970s the federal government came under intense pressures to curtail labour cost and inflation. In 1975, the [[Liberal Party of Canada|Liberal]] government of [[Pierre Trudeau]] introduced mandatory price and wage controls. Under the new law, wages increases were monitored and those ruled to be unacceptably high were rolled back by the government. |

|||

Pressures on unions continued into the 1980s and '90s. Private sector unions faced plant closures in many manufacturing industries and demands to reduce wages and increase productivity. Public sector unions came under attack by federal and provincial governments as they attempted to reduce spending, reduce taxes and balance budgets. Legislation was introduced in many jurisdictions reversing union collective bargaining rights, and many jobs were lost to contractors.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mapleleafweb.com/old/education/spotlight/issue_51/history.html |title=History of Unions in Canada |access-date=2013-07-15 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130727111519/http://www.mapleleafweb.com/old/education/spotlight/issue_51/history.html |archive-date=27 July 2013 }} Retrieved 14 July 2013.</ref> |

|||

Prominent domestic unions in Canada include [[ACTRA]], the [[Canadian Union of Postal Workers]], the [[Canadian Union of Public Employees]], the [[Public Service Alliance of Canada]], the [[National Union of Public and General Employees]], and [[Unifor]]. International unions active in Canada include the [[International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees]], [[United Automobile Workers]], [[United Food and Commercial Workers]], and [[United Steelworkers]]. |

|||

===Continental Europe=== |

|||

[[Trade unions in Germany]] have a history reaching back to the [[German revolutions of 1848-1849]], and still play an important role in the [[Economy of Germany|German economy]] and society. In 1875, the [[Social Democratic Party of Germany]] (SPD) was formed, and at first supported the forming of unions who were not directly affiliated with the Social Democratic Party.{{sfn|Schneider|1991}} The SPD instead insisted on the primacy of politics, and refused to emphasize support for union goals and methods.{{sfn|Moses|pages=1-19}} During the rise of the [[Nazi Party]], the trade unions did not recognise the threat and failed to actively oppose Adolf Hitler.{{sfn|Braunthal|1956}} Today, the largest labour organisation is the [[German Trade Union Confederation]], which represented more than 6 million workers in 2011.<ref>{{cite web |last=Fulton |first=L. |date=2015 |title=Trade Unions. Worker Participation. SEEurope Network |url=http://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Germany |url-status=live |access-date=2017-11-15 |website=Worker-Participation.eu |publisher=SEEurope Network}}</ref> |

|||

[[Trade unions in Belgium]] have one of the highest percentages of trade union membership, with 65% of workers belonging to a union. The biggest trade union federations in the country are the Christian democrat [[Confederation of Christian Trade Unions]] (ACV-CSC),<ref>{{cite web |title=Aantal leden christelijke vakbond neemt jaar na jaar toe |url=http://www.hln.be/hln/nl/957/Binnenland/article/detail/1166041/2010/10/05/Aantal-leden-christelijke-vakbond-neemt-jaar-na-jaar-toe.dhtml |access-date=16 January 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=130 jaar ACV-geschiedenis |url=https://www.acv-online.be/acv-online/het-acv/Wie-zijn-we/Geschiedenis/Geschiedenis.html |access-date=16 January 2018}}</ref> the socialist [[General Federation of Belgian Labour]] (ABVV-FGTB),<ref>{{cite web |title=Hoeveel leden telt het ABVV? – Vlaams ABVV – Socialistische vakbond in Vlaanderen – Algemeen Belgisch Vakverbond ABVV |url=http://www.vlaamsabvv.be/art/pid/13618/Hoeveel-leden-telt-het-ABVV.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111219131851/http://www.vlaamsabvv.be/art/pid/13618/Hoeveel-leden-telt-het-ABVV.htm |archive-date=19 December 2011 |access-date=16 January 2018 |website=www.vlaamsabvv.be}}</ref> and the classical liberal [[General Confederation of Liberal Trade Unions of Belgium]] (ACLVB-CGSLB).<ref>{{cite web |date=12 October 2015 |title=Structuur en kerncijfers van de ACLVB |url=http://www.aclvb.be/over-aclvb/structuurkerncijfers/ |access-date=16 January 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=12 October 2015 |title=Geschiedenis van de ACLVB |url=http://www.aclvb.be/over-aclvb/historiek/ |access-date=16 January 2018}}</ref> |

|||

[[Trade unions in Spain]] have a tumultuous history, as during the [[Spanish Civil War]], [[syndicalists]] took control over much of the country. Unions were particularly present in [[Revolutionary Catalonia]], with organisations like the [[anarcho-syndicalist]] [[Confederación Nacional del Trabajo|CNT]] organising throughout Spain.<ref>https://mirror.anarhija.net/theanarchistlibrary.org/mirror/s/sd/sam-dolgoff-editor-the-anarchist-collectives.lt.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=March 2022}}</ref> Following the loss of the civil war to the fascist and dictator [[Francisco Franco]], trade unions were seen as a threat and all existing trade unions were banned. The [[Spanish Syndical Organization]] as the only legal Spanish trade union, with the organisation existing to maintain Franco's power, and the former trade unions were forced underground.<ref>{{cite web |last=Pegenaute |first=Luis |date= |title=Censoring Translation and Translation as Censorship: Spain under Franco |url=https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/files/pegenaute-1999.pdf |access-date=15 February 2022 |website=www.arts.kuleuven.be}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Romanos |first1=Eduardo |year=2014 |title=Emotions, Moral Batteries and High-Risk Activism: Understanding the Emotional Practices of the Spanish Anarchists under Franco's Dictatorship |journal=Contemporary European History |volume=23 |issue=4 |pages=545–564 |doi=10.1017/S0960777314000319 |jstor=43299690 |s2cid=145621496}}</ref> During the [[Spanish transition to democracy]], trade unions became legal once again. Today, cooperatives, such as the [[Mondragon Corporation]], employ large parts of the Spanish population.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Syndicalism and the influence of anarchism in France, Italy and Spain |url=https://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/10096/3/Anarchist_Studies_Syndicalism.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210303152644/https://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/10096/3/Anarchist_Studies_Syndicalism.pdf |archive-date=3 March 2021 |access-date=2 November 2020}}</ref> |

|||

==== Northern Europe ==== |

|||

[[File:Striking workers organised in the Norwegian labour union UNIO.JPG|thumb|Workers on strike in Oslo, Norway, 2012]] |

|||

Trade unions have a long tradition in [[Scandinavia]]n and [[Nordic countries|Nordic]] society. which began in the mid-19th century, they today have a large impact on the nature of employment and workers' rights in those countries, with the world's highest rates of union membership.<ref>Anders Kjellberg (2022) [https://portal.research.lu.se/sv/publications/the-nordic-model-of-industrial-relations ''The Nordic Model of Industrial Relations'']. Lund: Department of Sociology]</ref> As of 2018, the percentage of workers belonging to a union (trade union density) was 90.4% in [[Iceland]], 67.2% in [[Denmark]], 66.1% in [[Sweden]], 64.4% in [[Finland]] and 52.5% in [[Norway]], while it is unknown in [[Greenland]], [[Faroe Islands]] and [[Åland]].<ref>[https://twitter.com/OECD/status/1123875322653442048/photo/1 "Trade Union Density"] OECD. Accessed: 06 October 2019.</ref> Excluding full-time students working part-time, Swedish union density was 68% in 2019.<ref>Anders Kjellberg (2020) [https://portal.research.lu.se/portal/en/publications/kollektivavtalens-tackningsgrad-samt-organisationsgraden-hos-arbetsgivarfoerbund-och-fackfoerbund(384bb031-c144-442b-a02b-44099819d605).html ''Kollektivavtalens täckningsgrad samt organisationsgraden hos arbetsgivarförbund och fackförbund''], Department of Sociology, Lund University. Studies in Social Policy, Industrial Relations, Working Life and Mobility. Research Reports 2020:1, Appendix 3 (in English) Table A</ref> In all the Nordic countries with a [[Ghent system]]—Sweden,<ref>Anders Kjellberg (2011) [http://portal.research.lu.se/portal/files/3462138/2064087.pdf "The Decline in Swedish Union Density since 2007"] ''Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies'' (NJWLS) Vol. 1. No 1 (August 2011), pp. 67–93</ref> Denmark and [[Finland]]—union density is about 70%. The considerably raised membership fees of Swedish union unemployment funds implemented by the centre-right [[Reinfeldt government]] in January 2007 caused large drops in membership in both unemployment funds and trade unions. From 2006 to 2008, union density declined by six percentage points: from 77% to 71%.<ref>Anders Kjellberg [http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=1964092&fileOId=2064087 "The Decline in Swedish Union Density since 2007"] ''Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies'' (NJWLS) Vol. 1. No 1 (August 2011), pp. 67–93</ref><ref>Anders Kjellberg (2020) [https://portal.research.lu.se/portal/en/publications/den-svenska-modellen-i-en-oviss-tid(11ad3d7f-b363-4e46-834f-cae7013939dc).html ''Den svenska modellen i en oviss tid. Fack, arbetsgivare och kollektivavtal på en föränderlig arbetsmarknad – Statistik och analyser: facklig medlemsutveckling, organisationsgrad och kollektivavtalstäckning 2000–2029"'']. Stockholm: Arena Idé 2020</ref><ref>Anders Bruhn, Anders Kjellberg and Åke Sandberg (2013) [http://portal.research.lu.se/portal/files/19441202/Nordic_lights_kapitel_4_Bruhn_Kjellberg_Sandberg_Correct.pdf "A New World of Work Challenging Swedish Unions"] in Åke Sandberg (ed.) ''Nordic Lights. Work, Management and Welfare in Scandinavia''. Stockholm: SNS (pp. 155–160)</ref> |

|||

In all three [[Baltic countries]], trade unions were an universal aspect of life for workers' whilst under the rule of the [[Soviet Union]], with the system closely integrated with the [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union]]. After the regaining of their independence, the trade unions in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia have experienced a rapid loss of membership and [[economic power]], while the inverse occurring for employers' organisations. Low financial and organisational capacity caused by declining membership adds to the problem of interest definition, aggregation and [[protection]] in [[negotiations]] with employers' and state organisations.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dvorak |first1=Jaroslav |last2=Karnite |first2=Raita |last3=Guogis |first3=Arvydas |date=26 January 2018 |title=The Characteristic Features of Social Dialogue in the Baltics |url=https://www.zurnalai.vu.lt/STEPP/article/view/11425 |journal=Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika |volume=16 |issue=16 |pages=26–36 |doi=10.15388/STEPP.2018.16.11425 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Historical legitimacy is one of the negative factors that determine low associational power.<ref name="pjms.zim.pcz.pl">Dvorak, J., Civinskas, R. (2018). The Determinants of Cooperation and the Need for Better Communication between Stakeholders in EU Countries: The Case of Posted Workers. Polish Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 18 (1), pp. 94–106 https://pjms.zim.pcz.pl/resources/html/article/details?id=183839</ref> |

|||

===India=== |

|||

{{Main|Trade unions in India}} |

|||

[[File:Trade Unions Rally.jpg|thumb|All Trade Unions' Rally in [[Udaipur]], [[Rajasthan]]]] |

|||

In India, the Trade Union movement is generally divided on political lines. According to provisional statistics from the [[Ministry of Labour and Employment (India)|Ministry of Labour]], trade unions had a combined membership of 24,601,589 in 2002. As of 2008, there are 12 Central Trade Union Organisations (CTUO) recognized by the Ministry of Labour.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.labourfile.org/superAdmin/Document/113/table%201.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111003061752/http://www.labourfile.org/superAdmin/Document/113/table%201.pdf |archive-date=3 October 2011 |title=Table 1: Aggregate data on membership of CTUOs 1989 to 2002 (Provisional) | website=labourfile.org}}</ref> The forming of these unions was a big deal in India. It led to a big push for more regulatory laws which gave workers a lot more power.<ref>{{cite web |last1= Sengupta |first1= Meghna |title= Trade Unions in India |url= http://www.pocketlawyer.com/blog/trade-unions-india/ |website= Pocket Lawyer |access-date= 2017-11-15 |archive-date= 16 November 2017 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20171116131308/http://www.pocketlawyer.com/blog/trade-unions-india/ |url-status= dead }}</ref> |

|||

[[All India Trade Union Congress]] is the oldest [[trade union federation]] in India. It is a left supported organisation. A trade union with nearly 2,000,000 members is the Self Employed Women's Association (SEWA) which protects the rights of Indian women working in the informal economy. In addition to the protection of rights, SEWA educates, mobilizes, finances, and exalts their members' trades.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Datta|first=Rekah|title=From Development to Empowerment: The Self-Employed Women's Association in India|journal=International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society}}</ref> Multiple other organisations represent workers. These organisations are formed upon different political groups.<ref>Bhattacharya, Gautam (2022). "Trade Unionism in Competitive Politics: The Story of an Arrangement Clerk", The Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 57, No. 4, April 2022 (pg.702-712)</ref> These different groups allow different groups of people with different political views to join a Union.<ref>{{cite web |last= Chand |first=Smriti |title= 6 Major Central Trade Unions of India |url= http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/trade-unions/6-major-central-trade-unions-of-india-trade-unions/26113 |website= Your Article Library |access-date= 2017-11-15|date=17 February 2014 }}</ref> |

|||

===Japan=== |

|||

{{Main|Labor unions in Japan}} |

|||

[[File:NUGW May Day 2011.jpg|thumb|alt=NUGW May Day 2011|2011 [[Zenrokyo|National Trade Union Council (''Zenrokyo'')]] [[International Workers' Day#Japan|May Day]] march, Tokyo]] |

|||

Trade unions emerged in Japan in the second half of the [[Meiji period]] as the country underwent a period of rapid [[industrialization]].<ref name="Nimura">Nimura, K. [http://oohara.mt.tama.hosei.ac.jp/nk/English/eg-formation.html ''The Formation of Japanese Labor Movement: 1868–1914''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111001233543/http://oohara.mt.tama.hosei.ac.jp/nk/English/eg-formation.html |date=1 October 2011 }} (Translated by Terry Boardman). Retrieved 11 June 2011</ref> Until 1945, however, the labour movement remained weak, impeded by lack of legal rights,<ref name="Cross">Cross Currents. [http://www.crosscurrents.hawaii.edu/content.aspx?lang=eng&site=japan&theme=work&subtheme=UNION&unit=JWORK079 Labor unions in Japan.] CULCON. Retrieved 11 June 2011</ref> [[anti-union]] legislation,<ref name="Nimura" /> management-organised factory councils, and political divisions between "cooperative" and radical unionists.<ref name="Weathers">Weathers, C. (2009). Business and Labor. In William M. Tsutsui (Ed.), ''A Companion to Japanese History'' (pp. 493–510). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.</ref> In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the [[Occupation of Japan|US Occupation]] authorities initially encouraged the formation of independent unions.<ref name="Cross" /> Legislation was passed that enshrined the right to organise,<ref>Jung, L. (30 March 2011). [http://www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/ifpdial/info/national/jp.htm#tu National Labour Law Profile: Japan.] ILO. Retrieved 10 June 2011</ref> and membership rapidly rose to 5 million by February 1947.<ref name="Cross" /> The organisation rate, however, peaked at 55.8% in 1949 and subsequently declined to 18.2% (2006).<ref name="Jil">Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. [http://www.jil.go.jp/english/laborsituation/2009-2010/detailed_2009-2010.pdf Labor Situation in Japan and Analysis: 2009/2010.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110927061114/http://www.jil.go.jp/english/laborsituation/2009-2010/detailed_2009-2010.pdf |date=27 September 2011 }} Retrieved 10 June 2011</ref> The labour movement went through a process of reorganisation from 1987 to 1991<ref>Dolan, R. E. & Worden, R. L. (Eds.). ''Japan: A Country Study''. [http://countrystudies.us/japan/104.htm Labor Unions, Employment and Labor Relations.] Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1994. Retrieved 12 June 2011</ref> from which emerged the present configuration of three major trade union federations, [[RENGO|Rengo]], [[Zenroren]], and [[Zenrokyo]], along with other smaller national union organisations. |

|||

===Latin America=== |

|||

{{Further|Mexican labor law|Trade unions in Colombia|Trade unions in Costa Rica}} |

|||

Historically, unions in Mexico were part of a state institutional system where, from 1940 until the 1980s, they did not operate independently and were largely controlled by the ruling party.<ref name="BotzJay01052010" /> During this period, the primary aim of the trade unions was to primarily carry out the state's economic policy which peaked in the mid 20th century with the so-called "[[Mexican Miracle]]". This policy saw rising incomes and improved standards of living, however, the main beneficiaries were the wealthy.<ref name="BotzJay01052010" /> In the 1980s, Mexico began adhering to the [[neoliberal]] [[Washington Consensus]], selling off state-owned industries to private owners, who had an antagonistic attitude towards unions, which, accustomed to [[Sweetheart deal|comfortable relationships]] with the state, were not prepared to fight back. A movement of [[New unionism|new unions]] began to emerge under a more independent model, while the former institutionalized unions had become very corrupt, violent, and led by gangsters. From the 1990s onwards, this new model of independent unions prevailed, a number of them represented by the National Union of Workers.<ref name="BotzJay01052010">[[Dan La Botz]] ''[http://therealnews.com/t2/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=31&Itemid=74&jumival=5059 U.S.-supported Economics Spurred Mexican Emigration, pt.1] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019161335/http://therealnews.com/t2/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=31&Itemid=74&jumival=5059 |date=19 October 2017 }}'', interview at ''[[The Real News]]'', 1 May 2010.</ref><ref>Murillo, M. Victoria. "From populism to neoliberalism: Labor unions and market reforms in Latin America." ''World Politics ''52.2 (2000): 135-168 [https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/10015452.pdf online.</ref> |

|||

Until around 1990 Colombian trade unions were among the strongest in [[Latin America]].<ref name="JFA11">American Center for International Labor Solidarity (2006), [http://www.solidaritycenter.org/files/ColombiaFinal.pdf Justice For All: The Struggle for Worker Rights in Colombia] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100717010518/http://www.solidaritycenter.org/files/ColombiaFinal.pdf|date=17 July 2010}}, p11</ref> However, the 1980s expansion of [[paramilitarism in Colombia]] saw trade union leaders and members increasingly targeted for assassination, and as a result Colombia has been the most dangerous country in the world for trade unionists for several decades.<ref>An [[ILO]] mission in 2000 reported that "the number of assassinations, abductions, death threats and other violent assaults on trade union leaders and unionized workers in Colombia is without historical precedent". According to the Colombian Government, during the period 1991–99 there were 593 assassinations of trade union leaders and unionized workers while the National Trade Union School holds that 1 336 union members were assassinated." – [[ILO]], 16 June 2000, [http://www.ilo.org/global/About_the_ILO/Media_and_public_information/Press_releases/lang--en/WCMS_007903/index.htm Special ILO Representative for cooperation with Colombia to be appointed by Director-General]</ref><ref>"By the 1990s, Colombia had become the most dangerous country in the world for unionists" – Chomsky, Aviva (2008), ''Linked labor histories: New England, Colombia, and the making of a global working class'', [[Duke University Press]], p11</ref><ref>"Colombia has the world's worst record on these assassinations..." – 20 November 2008, [https://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/11/20/colombia-not-time-trade-deal Colombia: Not Time for a Trade Deal]</ref> Between 2000 and 2010 Colombia accounted for 63.1% of trade unionists murdered globally.<ref name="ITUCres">[[International Trade Union Confederation]], 11 June 2010, [http://www.ituc-csi.org/ituc-responds-to-the-press-release.html?lang=en ITUC responds to the press release issued by the Colombian Interior Ministry concerning its survey]</ref> According to the [[International Trade Union Confederation]] (ITUC) there were 2832 murders of trade unionists between 1 January 1986 and 30 April 2010,<ref name="ITUCres" /> meaning that "on average, men and women trade unionists in Colombia have been killed at the rate of one every three days over the last 23 years."<ref name="ITUC2010">[[International Trade Union Confederation]] (2010), [http://survey.ituc-csi.org/+-Colombia-+.html Annual Survey of violations of trade union rights: Colombia]</ref>[[File:Agricultores, manifestación San José Costa Rica, enero 2011.jpg|thumb|Costa Rican farmers march for tax cuts, 2011|alt=Banner reads "Por una reforma justa a ley de bienes inmuebles, Sector Agropecuario"]] |

|||

In [[Costa Rica]], trade unions first appeared in the late 1800s to support workers in a variety of urban and industrial jobs, such as railroad builders and craft tradesmen.<ref name="SITRAPEQUIA">{{cite web |year=2014 |title=Historia del Sindicalismo |url=http://sitrapequia.or.cr/gestor/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=52 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140505020834/http://sitrapequia.or.cr/gestor/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=52 |archive-date=5 May 2014 |access-date=4 May 2014 |work=SITRAPEQUIA website |publisher=Sindicato de Trabajadores(as) Petroléros Químicos y Afines |language=es |location=San José}}</ref> After facing violent repression, such as during the 1934 United Fruit Strike, unions gained more power after the 1948 [[Costa Rican Civil War]].<ref name="SITRAPEQUIA" /> Today, Costa Rican unions are strongest in the public sector, including the fields of education and medicine, but also have a strong presence in the agricultural sector.<ref name="SITRAPEQUIA" /> In general, Costa Rican unions support government regulation of the banking, medical, and education fields, as well as improved wages and working conditions.<ref>{{cite news |last=Herrera |first=Manuel |date=30 April 2014 |title=Sindicatos alzarán la voz contra modelo neoliberal en celebraciones del 1° de mayo |language=es |newspaper=La Nacion |location=San Jose |url=http://www.nacion.com/nacional/trabajo/Sindicatos-alzaran-modelo-neoliberal-celebraciones_0_1411658998.html |access-date=7 May 2014}}</ref> |

|||

===United Kingdom=== |

|||

{{Main|Trade unions in the United Kingdom|History of trade unions in the United Kingdom}} |

|||

[[File:Leeds public sector pensions strike in November 2011 9.jpg|thumb|Public sector workers in [[Leeds]] striking over pension changes by the government in November 2011]] |

|||

Moderate [[New Model Union]]s dominated the union movement from the mid-19th century and where trade unionism was stronger than the political labour movement until the formation and growth of the [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour Party]] in the early years of the 20th century. |

|||

Trade unionism in the United Kingdom was a major factor in some of the economic crises during the 1960s and the 1970s, culminating in the "[[Winter of Discontent]]" of late-1978 and early-1979, when a significant percentage of the nation's public sector workers went on strike. By this stage, some 12,000,000 workers in the United Kingdom were trade union members. However, the election victory of the [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative Party]] led by [[Margaret Thatcher]] at the [[1979 United Kingdom general election|1979 general election]], at the expense of Labour's [[James Callaghan]], saw substantial trade union reform which saw the level of strikes fall. |

|||

The level of trade union membership also fell sharply in the 1980s, and continued falling for most of the 1990s. The long decline of most of the industries in which manual trade unions were strong—e.g. steel, coal, printing, the docks—was one of the causes of this loss of trade union members.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/3526917.stm|title=The trade unions' long decline|date=8 March 2004|access-date=16 January 2014|work=[[BBC News]]|first=Steve|last=Schifferes}}</ref> |

|||

In 2011, there were 6,135,126 members in TUC-affiliated unions, down from a peak of 12,172,508 in 1980. Trade union density was 14.1% in the private sector and 56.5% in the public sector.<ref>{{cite web|work=EUROPA|url=http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/eiro/country/united.kingdom_3.htm|title=United Kingdom: Industrial relations profile|date=15 April 2013|access-date=16 January 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203054931/http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/eiro/country/united.kingdom_3.htm|archive-date=3 December 2013}}</ref> |

|||

===United States=== |

|||

{{Main|Labor unions in the United States|Labor history of the United States}} |

|||

Labor unions are legally recognized as representatives of workers in many industries in the United States. In the United States, unions were formed based on power with the people, not over the people like the government at the time.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Kazin|first1=Michael|title=The Populist Persuasion|url=https://archive.org/details/populistpersuasi00kazirich|url-access=registration|date=1995|publisher=BasicBooks|page=[https://archive.org/details/populistpersuasi00kazirich/page/154 154]|isbn=978-0465037933}}</ref> Their activity today centres on [[collective bargaining]] over wages, benefits and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and supporting endorsed candidates at the state and federal level. |

|||

Most unions in America are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organisations: the [[AFL–CIO]] created in 1955, and the [[Change to Win Federation]] which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL–CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues. |

|||

[[File:Midnight at the glassworks2.jpg|thumb|[[Child labour]]ers in an [[Indiana]] glass works. Labor unions have an objective interest in combating child labour.]] |

|||

In 2010, the percentage of workers belonging to a union in the United States (or total trade union "density") was 11.4%, compared to 18.3% in Japan, 27.5% in Canada and 70% in Finland.<ref>[http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD Trade Union Density] OECD. StatExtracts. Retrieved: 17 November 2011.</ref> |

|||

The most prominent unions are among [[public sector]] employees such as teachers, police and other non-managerial or non-executive federal, state, county and municipal employees. Members of unions are disproportionately older, male and residents of the Northeast, the Midwest, and California.<ref name=Yeselson>{{cite magazine|url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/plank/103928/not-bang-whimper-the-long-slow-death-spiral-americas-labor-movement|title=Not With a Bang, But a Whimper: The Long, Slow Death Spiral of America's Labor Movement|magazine=The New Republic|access-date=16 January 2018|date=6 June 2012|last1=Yeselson|first1=Richard}}</ref> |

|||

The majority of union members come from the public sector. Nearly 34.8% of public sector employees are union members. In the private sector, just 6.3% of employees are union members<ref name="BLS01272012">[http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm Union Members Summary] Bureau of Labor Statistics, 22 January 2021 Retrieved: 13 July 2021</ref>—levels not seen since the 1930s.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Devaney |first=Tim |title=Union membership at lowest point since 1930s |url=https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/jan/23/union-membership-at-lowest-point-since-1930s/ |access-date=2022-12-29 |website=The Washington Times |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

Union workers in the private sector average 10–30% higher pay than non-union in America after controlling for individual, job, and labour market characteristics.<ref>[http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1176&context=key_workplace 8-31-2004 Union Membership Trends in the United States] Gerald Mayer. Congressional Research Service. 31 Aug 2004</ref> Because of their inherently governmental function, public sector workers are paid the same regardless of union affiliation or non-affiliation after controlling for individual, job, and labour market characteristics.{{citation needed|date=May 2022}} |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 11:51, 12 February 2023

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

A trade union (

Trade unions typically fund their head office and legal team functions through regularly imposed fees called union dues. The delegate staff of the trade union representation in the

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled or unskilled workers (craft unionism),[2] a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism), or an attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism). The agreements negotiated by a union are binding on the rank-and-file members and the employer, and in some cases on other non-member workers. Trade unions traditionally have a constitution which details the governance of their bargaining unit and also have governance at various levels of government depending on the industry that binds them legally to their negotiations and functioning.

Originating in Great Britain, trade unions became popular in many countries during the

Definition

Since the publication of the

A modern definition by the Australian Bureau of Statistics states that a trade union is "an organisation consisting predominantly of employees, the principal activities of which include the negotiation of rates of pay and conditions of employment for its members."[6]

Recent historical research by Bob James puts forward the view that trade unions are part of a broader movement of

History

Trade guilds

A collegium was any association in

Modern trade unions

While a commonly held mistaken view holds modern trade unionism to be a product of

In the cities, trade unions encountered a large hostility in their early existence from employers and government groups; at the time, unions and unionists were regularly prosecuted under various restraint of trade and conspiracy statutes. This pool of unskilled and semi-skilled labour spontaneously organized in fits and starts throughout its beginnings,

Trade unions and collective bargaining were outlawed from no later than the middle of the 14th century, when the

By the 1810s, the first labour organisations to bring together workers of divergent occupations were formed. Possibly the first such union was the General Union of Trades, also known as the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1818 in Manchester. The latter name was to hide the organisation's real purpose in a time when trade unions were still illegal.[24]

National general unions

The first attempts at setting up a national

In 1834, the

More permanent trade unions were established from the 1850s, better resourced but often less radical. The

If it were possible for the working classes, by combining among themselves, to raise or keep up the general rate of wages, it needs hardly be said that this would be a thing not to be punished, but to be welcomed and rejoiced at. Unfortunately the effect is quite beyond attainment by such means. The multitudes who compose the working class are too numerous and too widely scattered to combine at all, much more to combine effectually. If they could do so, they might doubtless succeed in diminishing the hours of labour, and obtaining the same wages for less work. They would also have a limited power of obtaining, by combination, an increase of general wages at the expense of profits.[27]

Beyond this claim Mill also argued that, because individual workers have no basis for assessing the wages for a particular task, labor unions would lead to greater efficiency of the market system.[28]

Legalization, expansion and recognition

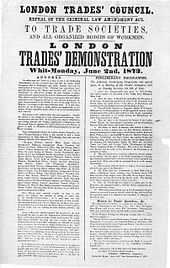

British trade unions were finally legalized in 1872, after a

This period also saw the growth of trade unions in other industrializing countries, especially the United States, Germany and France.

In the United States, the first effective nationwide labour organisation was the Knights of Labor, in 1869, which began to grow after 1880. Legalization occurred slowly as a result of a series of court decisions.[29] The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions began in 1881 as a federation of different unions that did not directly enroll workers. In 1886, it became known as the American Federation of Labor or AFL.

In Germany the

In France, labour organisation was illegal until 1884. The Bourse du Travail was founded in 1887 and merged with the Fédération nationale des syndicats (National Federation of Trade Unions) in 1895 to form the General Confederation of Labour.

In a number of countries during the 20th century, including in

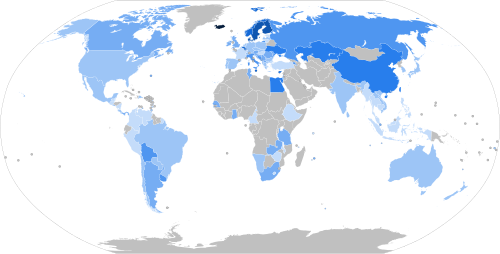

Prevalence worldwide

The union density has been steadily declining from the OECD average of 35.9% in 1998 to 27.9% in the year 2018.[33] The main reasons for these developments are a decline in manufacturing, increased globalization, and governmental policies.

The decline in

Structure and politics

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled workers (craft unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US[2]), a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, the UK and the US), or attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism, found in Australia, Canada, Germany, Finland, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US).[citation needed] These unions are often divided into "locals", and united in national federations. These federations themselves will affiliate with Internationals, such as the International Trade Union Confederation. However, in Japan, union organisation is slightly different due to the presence of enterprise unions, i.e. unions that are specific to a plant or company. These enterprise unions, however, join industry-wide federations which in turn are members of Rengo, the Japanese national trade union confederation.

In Western Europe, professional associations often carry out the functions of a trade union. In these cases, they may be negotiating for white-collar or professional workers, such as physicians, engineers or teachers. Typically such trade unions refrain from politics or pursue a more liberal politics than their blue-collar counterparts.[citation needed]

A union may acquire the status of a "

In other circumstances, unions may not have the legal right to represent workers, or the right may be in question. This lack of status can range from non-recognition of a union to political or criminal prosecution of union activists and members, with many cases of violence and deaths having been recorded historically.[36]

Unions may also engage in broader political or social struggle.

Unions are also delineated by the service model and the organizing model. The service model union focuses more on maintaining worker rights, providing services, and resolving disputes. Alternately, the organizing model typically involves full-time union organizers, who work by building up confidence, strong networks, and leaders within the workforce; and confrontational campaigns involving large numbers of union members. Many unions are a blend of these two philosophies, and the definitions of the models themselves are still debated.

In Britain, the perceived left-leaning nature of trade unions has resulted in the formation of a reactionary right-wing trade union called

In contrast, in several European countries (e.g. Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland), religious unions have existed for decades. These unions typically distanced themselves from some of the doctrines of orthodox Marxism, such as the preference of atheism and from rhetoric suggesting that employees' interests always are in conflict with those of employers. Some of these Christian unions have had some ties to centrist or conservative political movements and some do not regard strikes as acceptable political means for achieving employees' goals.[2] In Poland, the biggest trade union Solidarity emerged as an anti-communist movement with religious nationalist overtones[38] and today it supports the right-wing Law and Justice party.[39]

Although their political structure and autonomy varies widely, union leaderships are usually formed through democratic elections.[40] Some research, such as that conducted by the Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training,[41] argues that unionized workers enjoy better conditions and wages than those who are not unionized.

International unions

The oldest global trade union organisations include the

Labour law

Union law varies from country to country, as does the function of unions. For example, German and Dutch unions have played a greater role in management decisions through participation in corporate boards and co-determination than have unions in the United States.[44] Moreover, in the United States, collective bargaining is most commonly undertaken by unions directly with employers, whereas in Austria, Denmark, Germany or Sweden, unions most often negotiate with employers associations.

Concerning labour market regulation in the EU, Gold (1993)[45] and Hall (1994)[46] have identified three distinct systems of labour market regulation, which also influence the role that unions play:

- "In the Continental European System of labour market regulation, the government plays an important role as there is a strong legislative core of employee rights, which provides the basis for agreements as well as a framework for discord between unions on one side and employers or employers' associations on the other. This model was said to be found in EU core countries such as Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, and it is also mirrored and emulated to some extent in the institutions of the EU, due to the relative weight that these countries had in the EU until the EU expansion by the inclusion of 10 new Eastern European member states in 2004.

- In the Anglo-Saxon System of labour market regulation, the government's legislative role is much more limited, which allows for more issues to be decided between employers and employees and any union or employers' associations which might represent these parties in the decision-making process. However, in these countries, collective agreements are not widespread; only a few businesses and a few sectors of the economy have a strong tradition of finding collective solutions in labour relations. Ireland and the UK belong to this category, and in contrast to the EU core countries above, these countries first joined the EU in 1973.

- In the Nordic System of labour market regulation, the government's legislative role is limited in the same way as in the Anglo-Saxon system. However, in contrast to the countries in the Anglo-Saxon system category, this is a much more widespread network of collective agreements, which covers most industries and most firms. This model was said to encompass Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Here, Denmark joined the EU in 1973, whereas Finland and Sweden joined in 1995."[47]

The United States takes a more laissez-faire approach, setting some minimum standards but leaving most workers' wages and benefits to collective bargaining and market forces. Thus, it comes closest to the above Anglo-Saxon model. Also, the Eastern European countries that have recently entered into the EU come closest to the Anglo-Saxon model.

In contrast, in Germany, the relation between individual employees and employers is considered to be asymmetrical. In consequence, many working conditions are not negotiable due to a strong legal protection of individuals. However, the German flavor or works legislation has as its main objective to create a balance of power between employees organized in unions and employers organized in employers associations. This allows much wider legal boundaries for collective bargaining, compared to the narrow boundaries for individual negotiations. As a condition to obtain the legal status of a trade union, employee associations need to prove that their leverage is strong enough to serve as a counter-force in negotiations with employers. If such an employees association is competing against another union, its leverage may be questioned by unions and then evaluated in labour court. In Germany, only very few professional associations obtained the right to negotiate salaries and working conditions for their members, notably the medical doctors association Marburger Bund and the pilots association Vereinigung Cockpit. The engineers association Verein Deutscher Ingenieure does not strive to act as a union, as it also represents the interests of engineering businesses.

Beyond the classification listed above, unions' relations with political parties vary. In many countries unions are tightly bonded, or even share leadership, with a political party intended to represent the interests of the working class. Typically this is a

Historically, the

Shop types

Companies that employ workers with a union generally operate on one of several models:

- A closed shop (US) or a "pre-entry closed shop" (UK) employs only people who are already union members. The compulsory hiring hall is an example of a closed shop—in this case the employer must recruit directly from the union, as well as the employee working strictly for unionized employers.

- A union shop (US) or a "post-entry closed shop" (UK) employs non-union workers as well, but sets a time limit within which new employees must join a union.

- An agency shop requires non-union workers to pay a fee to the union for its services in negotiating their contract. This is sometimes called the Rand formula.

- An free riders) and those who do not. In the United States, state level right-to-work lawsmandate the open shop in some states. In Germany only open shops are legal; that is, all discrimination based on union membership is forbidden. This affects the function and services of the union.

An EU case concerning Italy stated that, "The principle of trade union freedom in the Italian system implies recognition of the right of the individual not to belong to any trade union ("negative" freedom of association/trade union freedom), and the unlawfulness of discrimination liable to cause harm to non-unionized employees."[48]

In Britain, previous to this EU jurisprudence, a series of laws introduced during the 1980s by Margaret Thatcher's government restricted closed and union shops. All agreements requiring a worker to join a union are now illegal. In the United States, the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 outlawed the closed shop.

In 2006, the European Court of Human Rights found Danish closed-shop agreements to be in breach of Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. It was stressed that Denmark and Iceland were among a limited number of contracting states that continue to permit the conclusion of closed-shop agreements.[49]

Impact

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2021) |

Economics

The academic literature shows substantial evidence that trade unions reduce

Research from Norway has found that high unionization rates lead to substantial increases in firm productivity, as well as increases in workers' wages.[60] Research from Belgium also found productivity gains, although smaller.[61] Other research in the United States has found that unions can harm profitability, employment and business growth rates.[62][63] Research from the Anglosphere indicates that unions can provide wage premiums and reduce inequality while reducing employment growth and restricting employment flexibility.[64]

In the United States, the outsourcing of labour to Asia, Latin America, and Africa has been partially driven by increasing costs of union partnership, which gives other countries a

Politics

In the United States, the weakening of unions has been linked to more favourable electoral outcomes for the Republican Party.[68][69][70] Legislators in areas with high unionization rates are more responsive to the interests of the poor, whereas areas with lower unionization rates are more responsive to the interests of the rich.[71] Higher unionization rates increase the likelihood of parental leave policies being adopted.[72] Republican-controlled states are less likely to adopt more restrictive labour policies when unions are strong in the state.[73]

Research in the United States found that American congressional representatives were more responsive to the interests of the poor in districts with higher unionization rates.[74] Another 2020 American study found an association between US state level adoption of parental leave legislation and trade union strength.[75]

In the United States, unions have been linked to lower racial resentment among whites.[76] Membership in unions increases political knowledge, in particular among those with less formal education.[77]

Health

In the United States, higher union density has been associated with lower suicide/overdose deaths.[78] Decreased unionisation rates in the United States have been linked to an increase in occupational fatalities.[79]

See also

- Critique of work

- Digital Product Passport

- Labor federation competition in the United States

- Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act

- Labour inspectorate

- List of trade unions

- Progressive Librarians Guild

- Project Labor Agreement

- Salt (union organizing)

- Smart contract: can be used in employment contracts

- Union busting

- Workplace politics

References

- ^ a b c Webb & Webb 1920.

- ^ a b c d Poole, M., 1986. Industrial Relations: Origins and Patterns of National Diversity. London UK: Routledge.

- ^ "Trade Union Dataset". OECD. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "Industrial relations". ILOSTAT. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ISSN 1743-4580.

- ^ "Trade Union Census". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ James 2001.

- ISBN 0684192799.

- ^ Hammurabi (1903). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Records of the Past. 2 (3). Translated by Sommer, Otto. Washington, DC: Records of the Past Exploration Society: 85. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

234. If a shipbuilder builds ... as a present [compensation].

- ^ Hammurabi (1904). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon" (PDF). Liberty Fund. Translated by Harper, Robert Francis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 83. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

§234. If a boatman build ... silver as his wage.

- ^ a b Hammurabi (1910). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Avalon Project. Translated by King, Leonard William. New Haven, CT: Yale Law School. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Hammurabi (1903). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Records of the Past. 2 (3). Translated by Sommer, Otto. Washington, DC: Records of the Past Exploration Society: 88. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

275. If anyone hires a ... day as rent therefor.

- ^ Hammurabi (1904). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon" (PDF). Liberty Fund. Translated by Harper, Robert Francis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 95. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

§275. If a man hire ... its hire per day.

- ^ The Documentary History of Insurance, 1000 B.C.–1875 A.D. Newark, NJ: Prudential Press. 1915. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- JSTOR 41539517.

- JSTOR 283119.

- ^ Welsh, Jennifer (23 September 2011). "Huge Ancient Roman Shipyard Unearthed in Italy". Live Science. Future. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ISBN 978-0807844984.

- ISBN 978-0198150688.

- ^ Perlman, Selig (1922). A History of Trade Unionism in the United States. New York: MacMillan. pp. 1–3.

- OCLC 55090137.

- ^ (1928). The Guild and the Trade Union. The Age.

- ^ Kautsky, Karl (April 1901). "Trades Unions and Socialism". International Socialist Review. 1 (10). Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Cole 2010, p. 3.

- History of Trade Unionism. London: Longmans Green and Co. pp. 120–124.

- ^ Webb & Webb 1894, p. 122.

- ^ Principles of Political Economy (1871)Book V, Ch.10 Archived 6 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, para. 5

- S2CID 157935634.

- ^ "Trade union". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- S2CID 145725063.

- S2CID 153980466.

- ^ Goodard, J. (2013). "Labour Law and Union Recognition in Canada: A Historical-Institutionalist Perspective". Queen's Law Journal. 38 (2): 391–417.

- ^ "Trade Union". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "The 10 Biggest Strikes in American History Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Fox Business. 9 August 2011

- SINALTRAINALmember José Onofre Esquivel Luna

- ^ "See the website of the Danish discount union "Det faglige Hus"". Danish.

- ^ Poland, Professor Jacek Tittenbrun of Poznan University. "The economic and social processes that led to the revolt of the Polish workers in the early eighties". www.marxist.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Solidarność popiera Kaczyńskiego jak kiedyś Wałęsę at news.money.pl (in Polish)

- ^ See E McGaughey, 'Democracy or Oligarchy? Models of Union Governance in the UK, Germany and US' (2017) ssrn.com

- ^ "Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training report" (PDF). Acirrt.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "WFTU » History". Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "International Trade Union Confederation". www.ituc-csi.org. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Bamberg, Ulrich (June 2004). "The role of German trade unions in the national and European standardisation process" (PDF). TUTB Newsletter. 24–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Gold, M., 1993. The Social Dimension – Employment Policy in the European Community. Basingstoke England UK: Macmillan Publishing

- ^ Hall, M., 1994. Industrial Relations and the Social Dimension of European Integration: Before and after Maastricht, pp. 281–331 in Hyman, R. & Ferner A., eds.: New Frontiers in European Industrial Relations, Basil Blackwell Publishing

- ^ Wagtmann, M.A. (2010): Module 3, Maritime & Port Wages, Benefits, Labour Relations. International Maritime Human Resource Management textbook modules. Available at: https://skydrive.live.com/?cid=f90c069a3e6bb729&id=F90C069A3E6BB729%21107#cid=F90C069A3E6BB729&id=F90C069A3E6BB729%21182

- ^ "Freedom of Association/Trade Union Freedom". Eurofound website. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "ECHR rules against Danish closed-shop agreements". Eurofound website.

- .

- ISSN 0033-5533.

- ISSN 1468-0289.

- ^ ehs1926 (12 February 2019). "Unions and American Income Inequality at Mid-Century". The Long Run. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ISBN 0674725115

- ^ Keith Naughton, Lynn Doan and Jeffrey Green (20 February 2015). As the Rich Get Richer, Unions Are Poised for Comeback. Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "A 2011 study drew a link between the decline in union membership since 1973 and expanding wage disparity. Those trends have since continued, said Bruce Western, a professor of sociology at Harvard University who co-authored the study."

- ^ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (4 June 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (Kindle Locations 1148–1149). Norton. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Barry T. Hirsch, David A. Macpherson, and Wayne G. Vroman, "Estimates of Union Density by State," Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 124, No. 7, July 2001.

- S2CID 219517711.

- S2CID 18351034.

- ISSN 0013-0133.

- ^ Van den Berg, Annette, Arjen van Witteloostuijn, and Olivier Van der Brempt. "Employee workplace representation in Belgium: Effects on firm performance." International Journal of Manpower (2017).

- ^ Hirsch, Barry T. "What do unions do for economic performance?." Journal of Labor Research 25, no. 3 (2004): 415–455.

- ^ Vedder, Richard, and Lowell Gallaway. "The economic effects of labor unions revisited." Journal of labor research 23, no. 1 (2002): 105-130.

- ^ Bryson, Alex. "Union wage effects." IZA World of Labor (2014).

- ^ Kramarz, Francis (19 October 2006). "Outsourcing, Unions, and Wages: Evidence from data matching imports, firms, and workers" (PDF). Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ Card David, Krueger Alan. (1995). Myth and measurement: The new economics of the minimum wage. Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press.

- ISBN 978-0202309699.

- ISSN 0261-3794.

- S2CID 220512676.

- ISSN 1537-5927.

- S2CID 204825962.

- .

- S2CID 216258517.

- ISSN 1537-5927.

- .

Event history analysis of state-level leave policy adoption from 1983 to 2016 shows that union institutional strength, particularly in the public sector, is positively associated with the timing of leave policy adoption.

- S2CID 221245953.

- S2CID 159071392.

- PMID 31845387.

Results – Overall, a 10% increase in union density was associated with a 17% relative decrease in overdose/suicide mortality (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70, 0.98), or 5.7 lives saved per 100 000 person‐years (95% CI: −10.7, −0.7). Union density's absolute (lives‐saved) effects on overdose/suicide mortality were stronger for men than women, but its relative effects were similar across genders. Union density had little effect on all‐cause mortality overall or across subgroups, and modeling suggested union‐density increases would not affect mortality inequities. Conclusions - Declining union density (as operationalized in this study) may not explain all‐cause mortality inequities, although increases in union density may reduce overdose/suicide mortality.

- S2CID 49187014. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

The Local Average Treatment Effect of a 1% decline in unionisation attributable to RTW is about a 5% increase in the rate of occupational fatalities. In total, RTW laws have led to a 14.2% increase in occupational mortality through decreased unionisation.

Bibliography

- Braunthal, Gerard (1956). "The German Free Trade Unions during the Rise of Nazism". Journal of Central European Affairs. 14 (4): 339–353.

- Cole, G. D. H. (2010). Attempts at General Union. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1136885167.

- James, Robert Noel (2001). Craft, Trade or Mystery. Tighes Hill, New South Wales.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Moses, John A. (December 1973). "The Trade Union Issue In German Social Democracy 1890-1900". Internationale Wissenschaftliche Korrespondenz zur Geschichte der Deutschen Arbeiterbewegung (19/20): 1–19.

- Schneider, Michael (1991). A brief history of the German trade unions. Bonn: JHW Dietz Nachfolger.

- Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice (1920). "Chapter I". History of Trade Unionism. Longmans and Co. London.

Further reading

- Docherty, James C. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Organized Labor.

- Docherty, James C. (2010). The A to Z of Organized Labor.

- St. James Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide : Major Events in Labor History and Their Impact ed by Neil Schlager (2 vol. 2004)

Britain

- Aldcroft, D. H. and Oliver, M. J., eds. Trade Unions and the Economy, 1870–2000. (2000).

- Campbell, A., Fishman, N., and McIlroy, J. eds. British Trade Unions and Industrial Politics: The Post-War Compromise 1945–64 (1999).

- )

- Clegg, H.A. (1985). 1911-1933. Vol. II.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Clegg, H.A. (1994). 1934-1951. Vol. III.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Davies, A. J. (1996). To Build a New Jerusalem: Labour Movement from the 1890s to the 1990s.

- Laybourn, Keith (1992). A history of British trade unionism c. 1770–1990.

- Minkin, Lewis (1991). The Contentious Alliance: Trade Unions and the Labour Party. p. 708.

- Pelling, Henry (1987). A history of British trade unionism.

- Wrigley, Chris, ed. British Trade Unions, 1945–1995 (Manchester University Press, 1997)

- Zeitlin, Jonathan (1987). "From labour history to the history of industrial relations". Economic History Review. 40 (2): 159–184.

- Directory of Employer's Associations, Trade unions, Joint Organisations. ISBN 0113612508.

Europe

- Berghahn, Volker R., and Detlev Karsten. Industrial Relations in West Germany (Bloomsbury Academic, 1988).

- European Commission, Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion: Industrial Relations in Europe 2010.

- Gumbrell-McCormick, Rebecca, and Richard Hyman. Trade unions in western Europe: Hard times, hard choices (Oxford UP, 2013).

- Kjellberg, Anders. "The Decline in Swedish Union Density since 2007", Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies (NJWLS) Vol. 1. No 1 (August 2011), pp. 67–93.

- Kjellberg, Anders (2017) The Membership Development of Swedish Trade Unions and Union Confederations Since the End of the Nineteenth Century (Studies in Social Policy, Industrial Relations, Working Life and Mobility). Research Reports 2017:2. Lund: Department of Sociology, Lund University.

- Markovits, Andrei. The Politics of West German Trade Unions: Strategies of Class and Interest Representation in Growth and Crisis (Routledge, 2016).

- McGaughey, Ewan, 'Democracy or Oligarchy? Models of Union Governance in the UK, Germany and US' (2017) ssrn.com

- Misner, Paul. Catholic Labor Movements in Europe. Social Thought and Action, 1914–1965 (2015). online review

- Mommsen, Wolfgang J., and Hans-Gerhard Husung, eds. The development of trade unionism in Great Britain and Germany, 1880–1914 (Taylor & Francis, 1985).

- Ribeiro, Ana Teresa. "Recent Trends in Collective Bargaining in Europe." E-Journal of International and Comparative Labour Studies 5.1 (2016). online Archived 11 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Upchurch, Martin, and Graham Taylor. The Crisis of Social Democratic Trade Unionism in Western Europe: The Search for Alternatives (Routledge, 2016).

United States

- Arnesen, Eric, ed. Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History (2006), 3 vol; 2064pp; 650 articles by experts excerpt and text search

- Beik, Millie, ed. Labor Relations: Major Issues in American History (2005) over 100 annotated primary documents excerpt and text search

- Boris, Eileen, and Nelson Lichtenstein, eds. Major Problems In The History Of American Workers: Documents and Essays (2002)

- Brody, David. In Labor's Cause: Main Themes on the History of the American Worker (1993) excerpt and text search

- Guild, C. M. (2021). Union Library Workers Blog: The Years 2019-2020 in Review. Progressive Librarian, 48, 110–165.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Foster Rhea Dulles. Labor in America: A History (2004), textbook, based on earlier textbooks by Dulles.

- Taylor, Paul F. The ABC-CLIO Companion to the American Labor Movement (1993) 237pp; short encyclopedia

- Zieger, Robert H., and Gilbert J. Gall, American Workers, American Unions: The Twentieth Century(3rd ed. 2002) excerpt and text search

Other

- Alexander, Robert Jackson, and Eldon M. Parker. A history of organized labor in Brazil (Greenwood, 2003).

- Dean, Adam. 2022. Opening Up By Cracking Down: Labor Repression and Trade Liberalization in Democratic Developing Countries. Cambridge University Press.

- Hodder, A. and L. Kretsos, eds. Young Workers and Trade Unions: A Global View (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2015). review

- Kester, Gérard. Trade unions and workplace democracy in Africa (Routledge, 2016).

- Lenti, Joseph U. Redeeming the Revolution: The State and Organized Labor in Post-Tlatelolco Mexico (University of Nebraska Press, 2017).

- Levitsky, Steven, and Scott Mainwaring. "Organized labor and democracy in Latin America." Comparative Politics (2006): 21-42 online.

- Lipton, Charles (1967). The Trade Union Movement of Canada: 1827–1959. (3rd ed. Toronto, Ont.: New Canada Publications, 1973).

- Orr, Charles A. "Trade Unionism in Colonial Africa" Journal of Modern African Studies, 4 (1966), pp. 65–81

- Panitch, Leo & Swartz, Donald (2003). From consent to coercion: The assault on trade union freedoms (third edition. Ontario: Garamound Press).

- Taylor, Andrew. Trade Unions and Politics: A Comparative Introduction (Macmillan, 1989).

- Visser, Jelle. "Union membership statistics in 24 countries." Monthly Labor Review. 129 (2006): 38+ online

- Visser, Jelle. "ICTWSS: Database on institutional characteristics of trade unions, wage setting, state intervention and social pacts in 34 countries between 1960 and 2007." Institute for Advanced Labour Studies, AIAS, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (2011). online

External links

- Australian Council of Trade Unions

- LabourStart international trade union news service

- RadioLabour

- New Unionism Network Archived 6 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Trade union membership 1993–2003 – European Industrial Relations Observatory report on membership trends in 26 European countries

- Trade union membership 2003–2008 – European Industrial Relations Observatory report on membership trends in 28 European countries

- Trade Union Ancestors – Listing of 5,000 UK trade unions with histories of main organisations, trade union "family trees" and details of union membership and strikes since 1900.

- TUC History online – History of the British union movement

- Short history of the UGT in Catalonia

- Younionize Global Union Directory Archived 5 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Labor rights in the USA

- Labor Notes magazine