Human rights in the Soviet Union

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

In practice, the Soviet government significantly curbed the very powerful

Soviet concept of human rights and legal system

According to the

The Soviet conception of human rights was very different from

The USSR and other countries in the Soviet Bloc had abstained from affirming the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), saying that it was "overly juridical" and potentially infringed on national sovereignty.[14]: 167–169 The Soviet Union later signed legally-binding human rights documents, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1973 (and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), but they were neither widely known or accessible to people living under Communist rule, nor were they taken seriously by the Communist authorities.[9]: 117 Sergei Kovalev recalled "the famous article 125 of the Constitution which enumerated all basic civil and political rights" in the Soviet Union. But when he and other prisoners attempted to use this as a legal basis for their abuse complaints, their prosecutor's argument was that "the Constitution was written not for you, but for American Negroes, so that they know how happy the lives of Soviet citizens are".[15]

Crime was determined not as the infraction of law, instead, it was determined as any action which could threaten the Soviet state and society. For example,

The purpose of

Freedom of political expression

In the 1930s and 1940s, political repression was practiced by the Soviet

Its theoretical basis was the theory of

Freedom of literary and scientific expression

Censorship in the Soviet Union was pervasive and strictly enforced.[19] This gave rise to Samizdat, a clandestine copying and distribution of government-suppressed literature. Art, literature, education, and science were placed under strict ideological scrutiny, since they were supposed to serve the interests of the victorious proletariat. Socialist realism is an example of such teleologically oriented art that promoted socialism and communism. All humanities and social sciences were tested for strict accordance with historical materialism.

All natural sciences were to be founded on the philosophical base of

According to the Soviet Criminal Code, agitation or propaganda carried on for the purpose of weakening Soviet authority, or circulating materials or literature that defamed the Soviet State and social system were punishable by imprisonment for a term of 2–5 years; for a second offense, punishable for a term of 3–10 years.[20]

Right to vote

According to

Economic rights

Freedoms of assembly and association

Workers were not allowed to organize free unions. All existing unions were organized and controlled by the state.[30] All political youth organizations, such as Pioneer movement and Komsomol served to enforce the policies of the Communist Party. Participation in unauthorized political organizations could result in imprisonment.[20] Organizing in camps could bring the death penalty.[20][need quotation to verify]

Freedom of religion

The Soviet Union promoted

Some actions against Orthodox priests and believers included torture; being sent to

Practicing Orthodox Christians were restricted from prominent careers and membership in communist organizations (e.g. the party and the

Freedom of movement

Emigration and any travel abroad were not allowed without explicit permission from the government. People who were not allowed to leave the country and campaigned for their right to leave in the 1970s were known as "

The passport system in the Soviet Union restricted migration of citizens within the country through the "propiska" (residential permit/registration system) and the use of internal passports. For a long period of Soviet history, peasants did not have internal passports, and could not move into towns without permission. Many former inmates received "wolf tickets" and were only allowed to live a minimum of 101 km away from city borders. Travel to closed cities and to the regions near USSR state borders was strongly restricted. An attempt to illegally escape abroad was punishable by imprisonment for 1–3 years.[20]

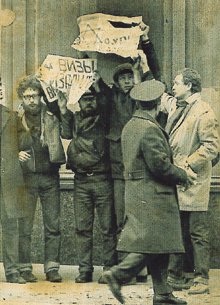

Human rights movement

Human rights activists in the Soviet Union were regularly subjected to harassment, repressions and arrests. In several cases, only the public profile of individual human rights campaigners such as Andrei Sakharov helped prevent a complete shutdown of the movement's activities.

A more organized human rights movement in the USSR grew out of the current of dissent of the late 1960s and 1970s known as "rights defenders (pravozashchitniki).[37] Its most important samizdat publication, the Chronicle of Current Events,[38] circulated its first number in April 1968, after the United Nations declared that it would be the International Year for Human Rights (20 years since Universal Declaration was issued), and continued for the next 15 years until closed down in 1983.

A succession of dedicated human rights groups were set up after 1968: the

The eight member countries of the

Over the next two years the Helsinki Groups would be harassed and threatened by the Soviet authorities and eventually forced to close down their activities, as leading activists were arrested, put on trial and imprisoned or pressured into leaving the country. By 1979, all had ceased to function.

Perestroika and human rights

The period from April 1985 to December 1991 witnessed dramatic change in the USSR.

In February 1987 KGB Chairman Victor Chebrikov reported to Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev that 288 people were serving sentences for offenses committed under Articles 70, 190-1 and 142 of the RSFSR Criminal Code; a third of those convicted were being held in psychiatric hospitals.[44] Most were released during the course of the year, spurred on by the death in prison of veteran dissident Anatoly Marchenko in December 1986.[45] Soon ethnic minorities, confessional groups and entire nations were asserting their rights, respectively, to cultural autonomy, freedom of religion and, led by the Baltic states, to national independence.

Just as

In the remaining two and a half years the rate of change accelerated. The

The authorities formed units of riot police OMON to deal with the mounting protests and rallies across the USSR. In Moscow, these culminated in a vast demonstration in January 1991, denouncing the actions of Gorbachev and his administration. The demonstrations in Lithuania, Tbilisi, Baku and Tajikistan have been suppressed resulting in deaths of many protesters [48][49]

See also

- Human rights movement in the Soviet Union

- Article 6 of the Soviet Constitution(1977)

- Crimes against humanity under communist regimes#Soviet Union

- Criticism of Communist party rule

- Droughts and famines in Russia and the Soviet Union

- 1921–22 famine in Tatarstan

- Holodomor

- Excess mortality in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin

- Antisemitism in Russia

- Human rights in Russia

- LGBT rights in Russia

- Racism in Russia

- Russian war crimes

- Mass killings in the Soviet Union

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Racism in the Soviet Union

- Soviet democracy

- Antisemitism in the Soviet Union

- Stalin and antisemitism

- Stalinism

- Stalin era

- Soviet war crimes

- Totalitarianism

References

- ^ "totalitarianism | Definition, Examples, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ Rutland, Peter (1993). The Politics of Economic Stagnation in the Soviet Union: The Role of Local Party Organs in Economic Management. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-521-39241-9. "after 1953 ...This was still an oppressive regime, but not a totalitarian one.".

- ^ Krupnik, Igor (1995). "4. Soviet Cultural and Ethnic Policies Towards Jews: A Legacy Reassessed". In Ro'i, Yaacov (ed.). Jews and Jewish Life in Russia and the Soviet Union. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-714-64619-0. "The era of 'social engineering' in the Soviet Union ended with the death of Stalin in 1953 or soon after; and that was the close of the totalitarian regime itself.".

- ^ von Beyme, Klaus (2014). On Political Culture, Cultural Policy, Art and Politics. Springer. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-319-01559-0. "The Soviet Union after the death of Stalin moved from totalitarianism to authoritarian rule.".

- ^ "Закон СССР от 14 марта 1990 г. N 1360-I "Об учреждении поста Президента СССР и внесении изменений и дополнений в Конституцию (Основной Закон) СССР"". 2017-10-10. Archived from the original on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- ^ ISBN 0-679-76184-5., pages 401–403.

- ^ a b Wyszyński, Andrzej (1949). Teoria dowodów sądowych w prawie radzieckim (PDF). Biblioteka Zrzeszenia Prawników Demokratów. pp. 153, 162.

- ^ S2CID 57570614.

- ^ Houghton Miffin Company (2006)

- ^ Lambelet, Doriane. "The Contradiction Between Soviet and American Human Rights Doctrine: Reconciliation Through Perestroika and Pragmatism." 7 Boston University International Law Journal. 1989. pp. 61–62.

- ISBN 978-0967533407.

- ^ ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 402–403

- ISBN 9780375760464.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Oleg Pshenichnyi (2015-08-22). "Засчитать поражение". Grani.ru. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ISBN 0-374-52738-5.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko Beria (Russian) Moscow, AST, 1999. Russian text online

- ISBN 0-8133-3744-5

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 9 – Mass Media and the Arts. The Library of Congress. Country Studies

- ^ ISBN 90-247-2538-0; p. 652

- ^ Stalin, quoted in IS WAR INEVITABLE? being the full text of the interview given by JOSEPH STALIN to ROY HOWARD as recorded by K. UMANSKY, Friends of the Soviet Union, London, 1936

- ISBN 0-393-04818-7, page 97

- ^ ISBN 978-90-411-1951-3.

- ^ "Статья 154. Спекуляция ЗАКОН РСФСР от 27-10-60 ОБ УТВЕРЖДЕНИИ УГОЛОВНОГО КОДЕКСА РСФСР (вместе с УГОЛОВНЫМ КОДЕКСОМ РСФСР)". zakonbase.ru. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- ^ Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 401. For a review, see "Davies & Weatcroft, 2004" (PDF). Warwick.

- ^ "Ukrainian Famine". Ibiblio public library and digital archive. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ISBN 9780230238558.

- ^ Nove, Alec (1952). An Economic History of the USSR 1917–1951. Penguin Books. pp. 373–375.

- ^ Vladimir G. Treml and Michael V. Alexeev,"The Second Economy and the Destabilization Effect of Its Growth on the State Economy in the Soviet Union: 1965-1989" (PDF), BERKELEY-DUKE OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON THE SECOND ECONOMY IN THE USSR, Paper No. 36, December 1993.

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 5. Trade Unions. The Library of Congress. Country Studies. 2005.

- ISBN 0-88141-180-9

- ^ a b L.Alexeeva, History of dissident movement in the USSR, in Russian

- ^ a b A.Ginzbourg, "Only one year", "Index" Magazine, in Russian

- ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Dumitru Bacu (1971) The Anti-Humans. Student Re-Education in Romanian Prisons Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Soldiers of the Cross, Englewood, Colorado. Originally written in Romanian as Piteşti, Centru de Reeducare Studenţească, Madrid, 1963

- ^ Adrian Cioroianu, Pe umerii lui Marx. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc ("On the Shoulders of Marx. An Incursion into the History of Romanian Communism"), Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2005

- ISBN 9780203412855.

- ^ A Chronicle of Current Events (in English)

- ^ An appeal to the UN Commission on Human Rights", A Chronicle of Current Events (8.10), 30 June 1969.

- ^ "The Committee for Human Rights in the USSR", A Chronicle of Current Events (17.4), 31 December 1970.

- ^ ISBN 9780691048598.

- ^ "A new public association", A Chronicle of Current Events (40.13), 12 May 1976.

- ISBN 978-0691048581.

- ^ Bukovsky Archive, KGB report to Gorbachev, 1 February 1987 (183-Ch).

- ^ "Release of a large group of political prisoners", Vesti iz SSSR, 1987 (15 February, 3.1) in Russian.

- ^ Bukovsky Archive, report by Shevardnadze, Yakovlev and Chebrikov, 4 December 1987 (2451-Ch).

- ^ Bukovsky Archive, Kryuchkov to Politburo, 27 July 1988 (1541-K).

- ^ Подрабинек, Александр (30 March 2011). Буковский против Горбачева. Не юбилейные показания [Bukovsky vs Gorbachev. Non-jubilee testimonies] (in Russian). Radio France Internationale.

- ^ Bukovsky Archive, Moscow Party committee to CPSU Central Committee, 23 January 1991 (Pb 223).

Bibliography

- Denial of human rights to Jews in the Soviet Union: hearings, Ninety-second Congress, first session. May 17, 1971. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1971.

- Human rights–Ukraine and the Soviet Union: hearing and markup before the Committee on Foreign Affairs and its Subcommittee on Human Rights and International Organizations, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress, First Session, on H. Con. Res. 111, H. Res. 152, H. Res. 193, July 28, July 30, and September 17, 1981. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1982.

- "Human rights: the dissidents v. Moscow". Time. Vol. 109, no. 8. 21 February 1977. p. 28.

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) ISBN 0-7679-0056-1

- Boim, Leon (1976). "Human rights in the USSR". Review of Socialist Law. 2 (1): 173–187. .

- Chalidze, Valeriĭ (1971). Important aspects of human rights in the Soviet Union; a report to the Human Rights Committee. New York: American Jewish Committee. OCLC 317422393.

- Chalidze, Valery (January 1973). "The right of a convicted citizen to leave his country". Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. 8 (1): 1–13.

- Conquest, Robert (1991) ISBN 0-19-507132-8.

- Conquest, Robert (1986) ISBN 0-19-505180-7.

- Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- Daniel, Thomas (2001). The Helsinki effect: international norms, human rights, and the demise of communism. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691048598.

- Dean, Richard (January–March 1980). "Contacts with the West: the dissidents' view of Western support for the human rights movement in the Soviet Union". Universal Human Rights. 2 (1): 47–65. JSTOR 761802.

- Fryer, Eugene (Spring 1979). "Soviet human rights: law and politics in perspective". JSTOR 1191202.

- Graubert, Judah (October 1972). "Human rights problems in the Soviet Union". Journal of Intergroup Relations. 2 (2): 24–31.

- Johns, Michael (Fall 1987). "Seventy years of evil: Soviet crimes from Lenin to Gorbachev". Policy Review: 10–23.

- Khlevniuk, Oleg & Kozlov, Vladimir (2004) The History of the Gulag : From Collectivization to the Great Terror (Annals of Communism Series) Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09284-9.

- Samatan, Marie (1980). Droits de l'homme et répression en URSS: l'appareil et les victimes [Human rights and repression in the USSR: mechanism and victims] (in French). Paris: Seuil. ISBN 978-2020057059.

- Pipes, Richard (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- Pipes, Richard (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5.

- Rummel, R.J. (1996) Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3.

- Szymanski, Albert (1984). Human rights: the USA and the USSR compared. Lawrence Hill & Co. ISBN 978-0882081588.

- Yakovlev, Alexander (2004). A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10322-0.

External links

- Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB – by Keith Armes.

- G.Yakunin, l.Regelson. Letters from Moscow. Religion and Human Rights in USSR. – Keston College Edition.

- Human Rights in the Soviet Society: - virtual exhibition about the Human Rights in the Soviet Society, by the Estonian Institute of Human Rights