History of the Soviet Union

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Literature |

| Music |

|

Sport |

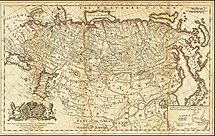

The history of

Before 1922, there were four independent Soviet Republics: the

The USSR gained and lost influence with other Communist countries over time. The occupying Soviet army facilitated the establishment of post-WWII Communist

Tensions with the central government led to constituent republics declaring independence starting in 1988, leading to the complete dissolution of the Soviet Union by 1991.

1917–1927: Establishment

The original philosophy of the state was primarily based on the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In its essence, Marx's theory stated that economic and political systems went through an inevitable evolution in form, by which the current capitalist system would be replaced by a Socialist state.

Displeased by the relatively few changes made by the Tsar after the

Under the control of the party, all politics and attitudes that were not strictly RCP (

1927–1953: Stalinism

The history of the

World War II, known as "the

1953–1964: Khrushchev Thaw

In the Soviet union, the eleven-year period from the death of

1964–1982: Era of Stagnation

The history of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982, referred to as the Brezhnev Era, covers the period of Leonid Brezhnev's rule of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). This period began with high economic growth and soaring prosperity, but ended with a much weaker Soviet Union facing social, political, and economic stagnation. The average annual income stagnated, because needed economic reforms were never fully carried out.

The collective leadership first set out to stabilize the Soviet Union and calm

The stabilization policy brought about after Khrushchev's removal established a ruling

While all modernized economies were rapidly moving to computerization after 1965, the USSR fell further and further behind. Moscow's decision to copy the

One of the greatest strengths of Soviet economy was its vast supplies of oil and gas; world oil prices quadrupled during the 1973–74 oil crisis, and rose again in 1979–1981, making the energy sector the chief driver of the Soviet economy, and was used to cover multiple weaknesses. At one point, Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin told the head of oil and gas production, "things are bad with bread. Give me 3 million tons [of oil] over the plan."[9] Former prime minister Yegor Gaidar, an economist looking back three decades, in 2007 wrote:

The hard currency from oil exports stopped the growing food supply crisis, increased the import of equipment and consumer goods, ensured a financial base for the arms race and the achievement of nuclear parity with the United States, and permitted the realization of such risky foreign-policy actions as the war in Afghanistan.[10]

1982–1991: Reforms and dissolution

The history of the Soviet Union from 1982 through 1991, spans the period from

Greater political and social freedoms, instituted by the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, created an atmosphere of open criticism of the Soviet government. The dramatic drop of the price of oil in 1985 and 1986 profoundly influenced actions of the Soviet leadership.[12]

Several

Historiography

Bibliography

- Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Civil War

- Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union

- Bibliography of the post-Stalinist Soviet Union

- Bibliography of Ukrainian history

- Historiography in the Soviet Union

Academic journals

See also

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- Islam in the Soviet Union

- Index of Soviet Union–related articles

- Ukrainian nationalism

References

- ISBN 978-1-60846-878-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-3452-5.

- ^ Stephen Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography 1888–1938 (Oxford University Press: London, 1980) p. 46.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-5647-5.

- ^ Ugri͡umov, Aleksandr Leontʹevich (1976). Lenin's Plan for Building Socialism in the USSR, 1917–1925. Novosti Press Agency Publishing House. p. 48.

- ISBN 978-1-349-05591-3.

- ^ James W. Cortada, "Public Policies and the Development of National Computer Industries in Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, 1940—80." Journal of Contemporary History (2009) 44#3 pp: 493-512, especially page 509-10.

- ^ Frank Cain, "Computers and the Cold War: United States restrictions on the export of computers to the Soviet Union and Communist China." Journal of Contemporary History (2005) 40#1 pp: 131-147. in JSTOR

- ^ Yergin, The Quest (2011) p 23

- ISBN 9780815731153.

- ^ WorldBook online

- ^ Gaidar, Yegor. "The Soviet Collapse: Grain and Oil". On the Issues: AEI online. American Enterprise Institute. Archived from the original on 2009-07-22. Retrieved 2009-07-09. (Edited version of a speech given November **, **** at the American Enterprise Institute.)

Further reading

- Conquest, Robert. The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties (1973).

- Daly, Jonathan and Leonid Trofimov, eds. "Russia in War and Revolution, 1914–1922: A Documentary History." (Indianapolis and Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing Company, 2009). ISBN 978-0-87220-987-9.

- Feis, Herbert. Churchill-Roosevelt-Stalin: The War they waged and the Peace they sought (1953).

- Figes, Orlando (1996). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924. Pimlico.

- Fenby, Jonathan. Alliance: the inside story of how Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill won one war and began another (2015).

- Firestone, Thomas. "Four Sovietologists: A Primer." National Interest No. 14 (Winter 1988/9), pp. 102–107 on the ideas of Zbigniew Brzezinski, Stephen F. Cohen, Jerry F. Hough, and Richard Pipes.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Russian Revolution. 199 pages. Oxford University Press; (2nd ed. 2001). ISBN 0-19-280204-6.

- Fleron, F.J. ed. Soviet Foreign Policy 1917–1991: Classic and Contemporary Issues (1991)

- Gorodetsky, Gabriel, ed. Soviet foreign policy, 1917–1991: a retrospective (Routledge, 2014).

- Haslam, Jonathan. Russia's Cold War: From the October Revolution to the Fall of the Wall (Yale UP, 2011) 512 pages

- Hosking, Geoffrey. History of the Soviet Union (2017).

- Keep, John L.H. Last of the Empires: A History of the Soviet Union, 1945–1991 (Oxford UP, 1995).

- Kotkin, Stephen. Stalin: Vol. 1: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 (2014), 976pp

- Kotkin, Stephen. Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941 (2017) vol 2

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. Passage Through Armageddon: The Russians in War and Revolution, 1914–1918. (New York, 1986). online

- McCauley, Martin. The Soviet Union 1917–1991 (2nd ed. 1993) online

- McCauley, Martin. Origins of the Cold War 1941–1949. (Routledge, 2015).

- McCauley, Martin. Russia, America, and the Cold War, 1949–1991 (1998)

- McCauley, Martin. The Khrushchev Era 1953–1964 (2014).

- Millar, James R. ed. Encyclopedia of Russian History (4 vol, 2004), 1700pp; 1500 articles by experts.

- Nove, Alec. An Economic History of the USSR, 1917–1991. (3rd ed. 1993) online w

- Paxton, John. Encyclopedia of Russian History: From the Christianization of Kiev to the Break-up of the USSR (Abc-Clio Inc, 1993).

- Pipes, Richard. Russia under the Bolshevik regime (1981). online

- Reynolds, David, and Vladimir Pechatnov, eds. The Kremlin Letters: Stalin's Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (2019)

- Service, Robert. Stalin: a Biography (2004).

- Shaw, Warren, and David Pryce-Jones. Encyclopedia of the USSR: From 1905 to the Present: Lenin to Gorbachev (Cassell, 1990).

- Shlapentokh, Vladimir. Public and private life of the Soviet people: changing values in post-Stalin Russia (Oxford UP, 1989).

- Taubman, William. Khrushchev: the man and his era (2003).

- Taubman, William. Gorbachev (2017)

- Tucker, Robert C., ed. Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation (Routledge, 2017).

- Westad, Odd Arne. The Cold War: A World History (2017)

- Wieczynski, Joseph L., and Bruce F. Adams. The modern encyclopedia of Russian, Soviet and Eurasian history (Academic International Press, 2000).