Culture of Poland

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Poland |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

|

Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

The culture of Poland (Polish: Kultura Polski) is the product of its geography and distinct historical evolution, which is closely connected to an intricate thousand-year history.[1] Poland has a Roman Catholic majority, and religion plays an important role in the lives of many Polish people.[2] The unique character of Polish culture developed as a result of its geography at the confluence of various European regions.

It is theorised and speculated that ethnic Poles are the combination of descendants of

The people of Poland have traditionally been seen as hospitable to artists from abroad and eager to follow cultural and artistic trends popular in other countries. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Polish focus on cultural advancement often took precedence over political and economic activity. These factors have contributed to the versatile nature of Polish art, with all its complex nuances.[3] Nowadays, Poland is a highly developed country that retains its traditions.

Poland has made significant contributions to the art, music, philosophy, mathematics, science, politics and literature of the Western World. The term which defines an individual's appreciation of Polish culture and customs is Polonophilia.

History

Cultural history of Poland can be traced back to the

Language

Polish (język polski, polszczyzna) is a language of the

Cuisine

Polish foods include

In the Middle Ages, as the cities of Poland grew larger in size and the food markets developed, the culinary exchange of ideas progressed & people got acquainted with new dishes and recipes. Some regions became well known for the type of sausage they made and many sausages of today still carry those original names. The peasants acknowledged their honorable judgment, allowing them to maintain nourished for longer periods of time.

The first known written mention of

According to a 2009 Ernst & Young report, Poland is Europe's third largest beer producer: Germany with 103 million hectolitres, UK with 49.5 million hl, Poland with 36.9 million hl. Following consecutive growth in the home market, Polish Union of the Brewing Industry Employers (Związek Pracodawców Przemysłu Piwowarskiego), which represents approximately 90% of the Polish beer market, announced during the annual brewing industry conference that consumption of beer in 2008 rose to 94 litres per capita, or 35,624 million hectolitres sold on domestic market. Statistically, a Polish consumer drinks some 92 litres of beer a year, which places it a third behind Germany. Drinking beer as a basic drink was typical during the

Soft drinks include "napoje gazowane" (carbonated drinks), "napoje bezalkoholowe" (non-alcoholic drinks) like water, tea, juice, coffee or kompot. Kompot is a non-alcoholic beverage made of boiled fruit, optionally with sugar and spices (clove or cinnamon), served hot or cold. It can be made of one type of fruit or a mixture, including apples, peaches, pears, strawberries or sour cherries. Also, Susz is type of kompot made with dried fruits, most commonly apples, apricots, figs. Traditionally served on Christmas Eve.

Among holiday meals, there is a traditional Christmas Eve supper called Wigilia. Another special occasion is Fat Thursday ("Tłusty Czwartek"), a Catholic feast celebrated on the last Thursday before the Lent. Traditionally it is a day when people eat large amounts of sweets and cakes that are afterwards forbidden until Easter day (see also: the Polish traditional Easter Breakfast).

-

Traditional Christmas Eve Pierogi

-

Kotlet schabowy served with potatoes and raw vegetable salads

-

Pączki plum jam doughnuts

-

Medieval kitchen from the 14th century

-

Mead Kurpiowski Dwójniak

-

Polish spoons from the 16th century

Architecture

Polish cities and towns reflect the whole spectrum of European styles. Poland's (along with Hungary's) eastern frontiers used to mark the outermost boundary of

History has not been good to Poland's architectural monuments. However, ancient structures have survived: castles, churches, and stately buildings, often unique in the regional or European context. Some of them have been painstakingly restored, like

.The architecture of

urban churches with influences of the orthodox and Armenian church.One of the best-preserved examples of the

-

Sukiennice (cloth-hall), with medieval Krakówratusz (city-hall) tower on the left.

-

Interior of theJewish heritage.

-

City hall in Gdańsk, where the architecture reflects historical ties to the Hanseatic League.

Art

The Młoda Polska (

-

Daniel Schultz

(1615–1683) -

Piotr Michałowski

(1800–1855) -

Jan Matejko

(1838–1893) -

Jacek Malczewski

(1854–1929)

-

Stanisław Wyspiański

(1869–1907) -

Witkiewicz "Witkacy"

(1885–1939) -

Zdzisław Beksiński

(1929–2005) -

Wilhelm Sasnal

(b. 1972)

Dance

Dance in Poland consists of a diverse array of traditional and contemporary forms of dance. Traditional dances are often an imporant part of cultural celebrations, and these dances vary across regions of the country. The national dances of Poland are

.Music

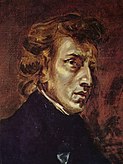

Artists from Poland, including famous composers like Karol Lipiński, Frédéric Chopin or Witold Lutosławski and traditional, regionalised folk musicians, create a lively and diverse music scene, which even recognizes its own music genres, such as sung poetry. Today in Poland, one may find trance, techno, house music, and heavy metal.

The origin of Polish music can be traced as far back as the 13th century, from which manuscripts have been found in

During the 16th century, mostly two musical groups – both based in

Among the best classical modern composers are Polish musicians Grażyna Bacewicz, Witold Lutosławski, Krzysztof Penderecki and Henryk Górecki.[citation needed]

The Polish world renown virtuosos of classical music of all time include composers

Jazz musician

Іn thе Роlіѕh muѕіс іnduѕtrу Rар ѕtаnd оut аѕ thе mоѕt рrоmіnеnt аnd wіdеlу rесоgnіzеd gеnrе. Роlіѕh rарреrѕ аrе сеlеbrаtеd fоr thеіr tаlеntѕ аnd асhіеvеmеntѕ.[7] Оvеr thе уеаrѕ, mоѕt Роlіѕh rарреrѕ ѕtuсk tо thе соntеmроrаrу rар muѕіс, but іn thе 21ѕt сеnturу ѕеvеrаl nеw‐gеnеrаtіоn аrtіѕtѕ bеgаn tо dіvеrѕіfу іntо оthеr gеnrеѕ іnсludіng Тrар. Νоtаblе Роlіѕh rарреrѕ іnсludе Magik, Peja and Popek. Whіlе іn tеrmѕ оf Rар thеrе аrе mаnу fеmаlе аrtіѕt but nоnе gаіnеd mаіnѕtrеаm рublісіtу.

Poland has one of the strongest and best-respected electronic dance music (EDM) scenes in Europe. One of the biggest record labels of EDM in Poland is Empire Records. The death metal band Vader is considered the most successful Polish Metal act and have gained commercial and critical praise internationally. Their career spans more than three decades with many international tours. They are often seen as a huge inspiration on modern Death Metal. Behemoth and Decapitated have found significant success inside and outside Poland. Both have toured extensively across Europe, America and, in the case of Decapitated, have recently toured Australia and New Zealand. Recently Indukti, Hate, Trauma, Crionics, Lost Soul and Lux Occulta have started to become well known outside of Poland. There is also an active grindcore, and a vigorous black metals scenes as well, the later led by Graveland, Darzamat, Kataxu, Infernal War and Vesania.[citation needed]

-

Frédéric Chopin

(1810–1849) -

Stanisław Moniuszko

(1819–1872) -

Henryk Wieniawski

(1835–1880) -

Karol Szymanowski

(1882–1937)

-

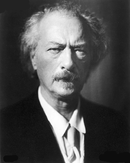

Ignacy Jan Paderewski

(1860–1941) -

Witold Lutosławski

(1913–1994) -

Henryk Górecki

(1933–2010) -

Krzysztof Penderecki

(1933–2020)

Literature

Since the arrival of Christianity and the subsequent access to Western European civilization, Poles developed a significant literary production in Latin. Conspicuous authors of the Middle Ages are among others Gallus Anonymus, Wincenty Kadłubek and Jan Długosz, an author of the monumental work on the history of Poland. With the arrival of the Renaissance, Poles came under the influence of the artistic patterns of the humanistic style, actively participating in the European issues of that time with their Latin works.[citation needed]

The origins of

In the early 20th century, many outstanding Polish literary works emerged from the new cultural exchange and Avant-Garde experimentation. The legacy of the

After the Second World War, many Polish writers found themselves in exile, with many of them clustered around the Paris-based "Kultura" publishing venture run by Jerzy Giedroyc. The group of emigre writers included Witold Gombrowicz, Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, Czesław Miłosz, and Sławomir Mrożek.

-

Jan Kochanowski

(1530–1584) -

Jan Andrzej Morsztyn

(1621–1693) -

Ignacy Krasicki

(1735–1801) -

Jan Potocki

(1761–1815)

-

Adam Mickiewicz

(1798–1855) -

Juliusz Słowacki

(1809–1849) -

Joseph Conrad

(1857–1924) -

Stefan Żeromski

(1864–1925)

-

Bruno Schulz

(1892–1942) -

Witold Gombrowicz

(1904–1969) -

Stanisław Lem

(1921–2006) -

Ryszard Kapuściński

(1932–2007)

| Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846–1916) |

Władysław Reymont (1865–1925) |

Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902–1991) |

Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004) |

Wisława Szymborska (1923–2012) |

Olga Tokarczuk (1962–) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philosophy

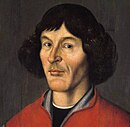

Polish philosophy drew upon the broader currents of European philosophy, and in turn contributed to their growth. Among the most momentous Polish contributions were made, in the 13th century, by the Scholastic philosopher and scientist Vitello, by Paweł Włodkowic—in early 15th and, by the Renaissance polymath Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century.[8]

Subsequently, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth partook in the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment, which for the multi-ethnic Commonwealth ended not long after the partitions and political annihilation that would last for the next 123 years, until the collapse of the three partitioning empires in World War I.

The period of

The collapse of the January 1863 Uprising prompted an agonising reappraisal of Poland's situation. Poles gave up their earlier practice of "measuring their goals by their aspirations" (Adam Mickiewicz) and buckled down to hard work and study. "[A] Positivist," wrote the novelist Bolesław Prus's friend, Julian Ochorowicz, was "anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."[9]

The 20th century brought a new quickening to Polish philosophy. There was growing interest in western philosophical currents. Rigorously trained Polish philosophers made substantial contributions to specialized fields—to

After

-

Vitello

(1230–1280/1314) -

Gregory of Sanok

(1403/1407–1477) -

Nicolaus Copernicus

(1473–1543) -

Frycz Modrzewski

(1503–1572)

-

Lwów–Warsaw school

(1895–1920/1930) -

Roman Ingarden

(1893–1970) -

Alfred Tarski

(1901–1983) -

PopeJohn Paul II

(1920–2005)

See also

Gallery

-

Open'er Festival in Gdynia is one of the biggest annual music festivals in Poland

-

Old Town of Zamość (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

References

- ISBN 0-7818-0200-8

- ^ GUS. "Infographic - Religiousness of Polish inhabitiants". stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, 2002–2007, An Overview of Polish Culture. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b c "History of vodka production, at the official page of Polish Spirit Industry Association (KRPS), 2007". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ "Pawilony polskie".

- ^ "The Music Courts of the Polish Vasas" (PDF). www.semper.pl. p. 244. Retrieved 2009-05-13.[dead link]

- ^ Polish Rap

- ^ Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Zarys dziejów filozofii w Polsce (A Brief History of Philosophy in Poland), p. 32.

- ^ Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Historia filozofii (History of Philosophy), vol. 3, p. 177.

- ^ Tatarkiewicz, Zarys..., p. 32.

- ^ Kazimierz Kuratowski, A Half Century of Polish Mathematics, pp. 23–24, 33.

- ^ Kazimierz Kuratowski, A Half Century of Polish Mathematics, p. 30 and passim.

External links

- Looking at Poland's History Through the Prism of Art

- Polonia Music The world of Polish heritage music!

- Polish Art Center A Treasury of Polish Heritage

- Pigasus Gallery Polish Poster, Music & Film

- Serpent.pl Albums from genre folk/ethno

- Read more about Polish culture at Culture.pl – the online magazine promoting Polish culture abroad, run by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute

![Polish art déco pavilion including its artworks representing the culture of Poland, Paris, 1925. The building was awarded the Grand Prix.[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Paris_1925_59878912.jpg/118px-Paris_1925_59878912.jpg)