Islam in Indonesia

Quranic Arabic[2]

|

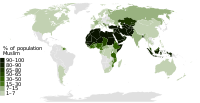

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

In terms of

Islam in Indonesia is considered to have

Islam in Indonesia

Distribution

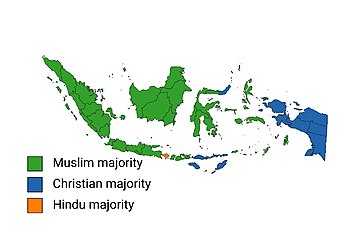

Muslims constitute a majority in most regions of

Internal migration has altered the demographic makeup of the country over the past three decades. It has increased the percentage of Muslims in formerly predominantly-Christian eastern parts of the country. By the early 1990s, Christians became a minority for the first time in some areas of the

Islam in Indonesia by province & region

This is a data table of the percentage of Muslims in Indonesia, provided by the Ministry of Religious Affairs:[1]

| Province | Muslim population | Total population | Muslim percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aceh (Highest Percentage of Muslims) | 5,356,635 | 5,432,312 | 98.61% |

| Bali | 434,941 | 4,304,574 | 10.10% |

| Bangka Belitung Islands | 1,344,903 | 1,490,418 | 90.24% |

| Banten | 11,686,756 | 12,321,660 | 94.85% |

| Bengkulu | 2,017,860 | 2,065,573 | 97.69% |

| Central Java | 36,773,442 | 37,783,666 | 97.33% |

| Central Kalimantan | 2,011,763 | 2,706,950 | 74.32% |

| Central Papua | 162,740 | 1,348,463 | 12.07% |

| Central Sulawesi | 2,450,867 | 3,099,717 | 79.07% |

| East Java | 40,179,566 | 41,311,181 | 97.26% |

| East Kalimantan | 3,446,652 | 3,941,766 | 87.44% |

| East Nusa Tenggara | 523,523 | 5,543,239 | 9.44% |

| Gorontalo | 1,191,484 | 1,215,387 | 98.03% |

| Highland Papua (Lowest Population and Percentage of Muslims) | 27,357 | 1,459,544 | 1.87% |

| Jakarta C. R. | 9,491,619 | 11,317,271 | 83.87% |

| Jambi | 3,514,415 | 3,696,044 | 95.09% |

| Lampung | 8,598,009 | 8,947,458 | 96.09% |

| Maluku | 997,724 | 1,893,324 | 52.70% |

| North Kalimantan | 533,675 | 726,989 | 73.41% |

| North Maluku | 1,005,727 | 1,346,267 | 74.70% |

| North Sulawesi | 849,253 | 2,666,821 | 31.85% |

| North Sumatra | 10,244,655 | 15,372,437 | 66.64% |

| Papua | 320,442 | 1,073,354 | 29.85% |

| Riau | 5,870,015 | 6,743,099 | 87.05% |

| Riau Islands | 1,671,242 | 2,133,491 | 78.33% |

| South Kalimantan | 4,054,044 | 4,178,229 | 97.03% |

| South Papua | 143,610 | 522,844 | 27.47% |

| South Sulawesi | 8,359,166 | 9,300,745 | 89.88% |

| South Sumatra | 8,508,999 | 8,755,074 | 97.19% |

| Southeast Sulawesi | 2,593,226 | 2,707,061 | 95.79% |

| Southwest Papua | 230,904 | 604,698 | 38.19% |

| West Java (Highest Population of Muslims) | 48,029,215 | 49,339,490 | 97.34% |

| West Kalimantan | 3,320,719 | 5,497,151 | 60.41% |

| West Nusa Tenggara | 5,361,920 | 5,534,583 | 96.88% |

| West Papua | 213,230 | 559,361 | 38.12% |

| West Sulawesi | 1,217,339 | 1,450,610 | 83.92% |

| West Sumatra | 5,528,423 | 5,664,988 | 97.59% |

| Yogyakarta S. R. | 3,433,129 | 3,693,834 | 92.94% |

| Region | Muslim population | Total population | Muslim % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Java | 149,593,727 | 155,767,102 | 96.04% |

| Kalimantan | 13,366,853 | 17,051,085 | 78.39% |

| Lesser Sunda Islands | 6,320,384 | 15,382,396 | 41.09% |

| Maluku Islands | 2,003,451 | 3,239,591 | 61.84% |

| Sumatra | 52,655,156 | 60,300,894 | 87.32% |

| Sulawesi | 16,661,335 | 20,440,341 | 81.51% |

| Western New Guinea | 1,098,283 | 5,568,264 | 19.72% |

| Indonesia | 241,699,189 | 276,534,400 | 87.02% |

Denominations

Division of Islam in Indonesia

Classical documentations divide Indonesian Muslims between "nominal" Muslims, or

In the contemporary era, distinction is often made between "traditionalism" and "modernism". Traditionalism, exemplified by the civil society organization

Kebatinan

Various other forms and adaptations of Islam are influenced by local cultures that hold different norms and perceptions throughout the archipelago.

Other branches

More recent currents of Islamic thoughts that have taken roots include

A small minority subscribe to the

Organizations

In Indonesia, civil society organizations have historically held distinct and significant weight within the Muslim society. These various institutions have contributed greatly to both the intellectual discourse and public sphere for the culmination of new thoughts and sources for communal movements.[31]: 18–19 60% of 200 million Indonesian Muslims identify either as Nahdlatul Ulama or Muhammadiyah, making these organizations a 'steel frame' of Indonesian civil society.[32]

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest traditionalist organization, focuses on many of the activities such as social, religious and education and indirectly operates a majority of the country's Islamic boarding schools. Claiming 40 to 60 million followers, NU is Indonesia's largest organization and perhaps the world's largest Islamic group.[32][33][34] Founded in 1926, NU has a nationwide presence but remains strongest in rural Java. It follows the ideology of Ahle Sunnah wal Jamaah with Sufism of Imam Ghazali and Junaid Bagdadi. Many NU followers give great deference to the views, interpretations, and instructions of senior NU religious figures, alternatively called Kyais or Ulama. The organization has long advocated religious moderation and communal harmony.[citation needed] On the political level, NU, the progressive Consultative Council of Indonesian Muslims (Masyumi), and two other parties were forcibly streamlined into a single Islamic political party in 1973—the United Development Party (PPP).[19] Such cleavages may have weakened NU as an organized political entity, as demonstrated by the NU withdrawal from active political competition, but as a popular religious force, NU showed signs of good health and a capacity to frame national debates.[19]

The leading national modernist social organization, Muhammadiyah, has branches throughout the country and approximately 29 million followers.[35] Founded in 1912, Muhammadiyah runs mosques, prayer houses, clinics, orphanages, poorhouses, schools, public libraries, and universities. On February 9,[year missing] Muhammadiyah's central board and provincial chiefs agreed to endorse a former Muhammadiyah chairman's presidential campaign. This marked the organization's first formal foray into partisan politics and generated controversy among members.

Some smaller Islamic organizations cover a broad range of Islamic doctrinal orientations. At one end of the ideological spectrum lies the controversial Islam Liberal Network (JIL), which aims to promote a pluralist and more liberal interpretation of Islamic thinking.

Equally controversial are groups at the other end of this spectrum such as

History

Spread of Islam (1200–1602)

There is evidence of Arab Muslim traders entering Indonesia as early as the 8th century.[12][21] However, it was not until the end of the 13th century that the spread of Islam began.[12] At first, Islam was introduced through Arab Muslim traders, and then the missionary activity by scholars. It was further aided by the adoption by the local rulers and the conversion of the elites.[21] The missionaries had originated from several countries and regions, initially from South Asia (i.e. Gujarat) and Southeast Asia (i.e. Champa),[38] and later from the southern Arabian Peninsula (i.e. Hadhramaut).[21]

In the 13th century, Islamic polities began to emerge on the northern coast of Sumatra. Marco Polo, on his way home from China in 1292, reported at least one Muslim town.[39] The first evidence of a Muslim dynasty is the gravestone, dated AH 696 (1297 CE), of Sultan Malik al Saleh, the first Muslim ruler of Samudera Pasai Sultanate. By the end of the 13th century, Islam had been established in Northern Sumatra.

In general, local traders and the royalty of major kingdoms were the first to adopt the new religion. The spread of Islam among the ruling class was precipitated as Muslim traders married the local women, with some of the wealthier traders marrying into the elite ruling families.[9] Indonesian people, as local rulers and the royals did, began to adopt Islam, and subsequently, their subjects mirrored their conversion. Although the spread was slow and gradual,[40] the limited evidence suggests that it accelerated in the 15th century, as the military power of Malacca Sultanate in the Malay Peninsula and other Islamic Sultanates that dominated the region were aided by episodes of Muslim coup such as in 1446, wars and superior control of maritime trading and ultimate markets.[40][41]

By the 14th century, Islam had been established in northeast Malaya, Brunei, the southwestern Philippines, and among some courts of coastal East and Central Java, and by the 15th century, in Malacca and other areas of the Malay Peninsula. to the east.

Indonesia's historical inhabitants were animists, Hindus, and Buddhists.[45] Through assimilation related to trade, royal conversion, and conquest,[citation needed] however, Islam had supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion of Java and Sumatra by the end of the 16th century. During this process, "cultural influences from the Hindu-Buddhist era were mostly tolerated or incorporated into Islamic rituals."[12] Islam did not obliterate the preexisting culture; rather, it incorporated and embedded the local customs and non-Islamic elements among rules and arts, and reframed them as the Islamic traditions.[21]

In part, the strong presence of Sufism has been considered a major enabler of this syncretism between Islam and other religions. Sufism retained strong influence especially among the Islamic scholars arrived during the early days of the spread of Islam in Indonesia, and many Sufi orders such as Naqshbandiyah and Qadiriyya have attracted new Indonesian converts. They have proceeded to branch into different local divisions. Sufi mysticism which had proliferated during this course had shaped the syncretic, eclectic and pluralist nature of Islam in Indonesian during the time.[21] Prolific Sufis from the Indonesian archipelago were already known in Arabic sources as far back as the 13th Century.[46] One of the most important Indonesian Sufis from this time is Hamzah Fansuri, a poet, and writer from the 16th century.[31]: 4 The preeminence of Sufism among Islam in Indonesian continued until the shift of external influence from South Asia to the Arabian Peninsula, whose scholars brought more orthodox teachings and perceptions of Islam.[21]

The gradual adoption of Islam by Indonesians was perceived as a threat by some ruling powers.[

Despite Islam being one of the most significant developments in Indonesian history, historical evidence remains fragmentary and uninformative. The understanding of how Islam arrived in Indonesia is limited; there is considerable debate among scholars about what conclusions can be drawn about the conversion of Indonesian peoples.[48] The primary evidence, at least of the earlier stages of the process, are gravestones and a few travelers' accounts, but these can only show that indigenous Muslims were in a certain place at a certain time. This evidence is insufficient to comprehensively explain more complicated matters, such as how lifestyles were affected by the new religion or how deeply it affected societies.

Early modern period (1700–1945)

The Dutch entered the region in the 17th century, attracted by its wealth established through the region's natural resources and trade.[49][b] The entering of the Dutch resulted in a monopoly of the central trading ports. However, this helped the spread of Islam, as local Muslim traders relocated to the smaller and remoter ports, establishing Islam into the rural provinces.[49] Towards the beginning of the 20th century, "Islam became a rallying banner to resist colonialism".[12]

During this time the introduction of steam-powered transportation and printing technology was facilitated by European expansion. As a result, the interaction between Indonesia and the rest of the Islamic world, particularly the Middle East, had significantly increased.[31]: 2 In Mecca, the number of pilgrims grew exponentially to the point that Indonesians were markedly referred as "rice of the Hejaz". The exchange of scholars and students was also increased. Around two hundred Southeast Asian students, mostly Indonesian, were studying in Cairo during the mid-1920s, and around two thousand citizens of Saudi Arabia were of Indonesian descent. Those who returned from the Middle East had become the backbone of religious training in pesantrens.[21]

Concurrently, a number of newly-founded religious thoughts and movements in the Islamic world had inspired the Islamic current in Indonesia. In particular,

Reformist movements had especially taken roots in the

A combination of reformist thoughts and the growing sense of sovereignty had led to the brief development of Islam as a vehicle for the political struggle against the Dutch colonialism. The earliest example is

However, Islam as a vehicle of Indonesian nationalism had gradually waned in the face of the emergence of secular nationalism and more radical political thoughts such as

Post-independence (since 1945)

Indonesia became the world's second-largest Muslim-majority country after its independence in 1945. The separation of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971 made it the world's most populous Muslim-majority country. Post-independence had seen the most significant upheaval of the Muslim society on various aspects of society. This owes to the independence, increased literacy and educational attainment among Muslims, funding from the Middle East, and all the more accelerated exchange between other Muslim countries.[21]

The subsequent development of the Muslim society had brought Indonesia even closer to the center of Islamic intellectual activity. A number of scholars and writers have contributed to the development of Islamic interpretations within the Indonesian context, often through the intellectual exchange between the foreign contemporaries.

Post-independence had also seen an expansion in the activity of Islamic organizations, especially regarding missionary activities (

Upon independence, there was significant controversy surrounding Islam's role in politics, which had caused enormous tensions. The contentions were mainly surrounding the position of Islam in the

During the New Order, there was an intensification of religious belief among Muslims.[71] Initially hoped as the ally of Islamic groups, the New Order quickly became the antagonist following its attempt to reform educational and marital legislation to more secular-oriented code. This met strong opposition, with marriage law left as Islamic code as a result. Suharto had also attempted at consolidating Pancasila as the only state ideology, which was also turned down by the fierce resistance of Islamic groups.[21] Under the Suharto regime, containment of Islam as a political ideology had led to all the Islamic parties forcibly unite under one government-supervised Islamic party, the United Development Party (PPP).[12] Certain Islamic organizations were incorporated by the Suharto regime, most notably MUI, DDII, and Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals (ICMI) to absorb the political Islam for the regime's gain.[72] With Suharto's resignation in 1998, "the structure that repressed religion and society collapsed."[12]

During the beginning of the

Currently, Muslims are considered fully represented in the democratically elected parliament.

Current President

Culture

Arts

Several artistic traditions in Indonesia, many of which existed since the pre-Islamic era, have absorbed Islamic influence and evolved in artistic expression and attachment of religious implications.

Batik

The Indonesian dyeing art known as

Wayang

The Indonesian performing art of

When Islam began spreading in Indonesia, the display of God or gods in human form was prohibited. Thus this style of painting and shadow play was suppressed. King Raden Patah of Demak, Java, wanted to see the wayang in its traditional form but failed to obtain permission from Muslim religious leaders. Religious leaders attempted to skirt the Muslim prohibition by converting the wayang golek into wayang purwa made from leather and displayed only the shadow instead of the puppets themselves.[citation needed]

Dance

The history of

Architecture

The

Only after the 19th century, the mosques began incorporating more orthodox styles imported during the Dutch colonial era. Architectural style during this era is characterized by

Clothing

The

The

The kerudung is an Indonesian Muslim women's

Festival

| and various special dishes are served.

Muslim holy days celebrated in Indonesia include the HajjThe government has a monopoly on organising the Saudi Government , an assertion that proved incorrect. Members of the House of Representatives have sponsored a bill to set up an independent institution, thus ending the department's monopoly.

Tabuik

Society

GenderTo a significant degree, the way in which Islam manifests in Indonesia's lifestyle is unique and reflective of Southeast Asian culture.[101] However, there have been several instances of discrimination for women in the work field, such as Hijabophobia, resulting in demonstrations.[102] Gender segregationMany Muslims in Indonesia have a relaxed view on social relations between sexes. Strict sex segregation is usually limited to religious settings, such as in mosques during prayer. It is common for boys and girls to study together in their classroom in both public and Islamic schools. Nevertheless, there is a growing influence of a more traditional, orthodox view of sex segregation in public places. This is done to avoid contact between opposite sexes; for example, some women wearing hijab might refuse to shake hands or converse with men. However, the number of sexual harassment cases in Indonesia have increased, with the majority of victims being women who wear hijab.[103] PoliticsAlthough it has an overwhelming Muslim majority, the country is neither an Islamic state nor an Islamic republic, similar to that of Turkey and Kazakhstan. From a Pew Research Center (PEW) opinion poll in 2010, Indonesia is the only country, among the five countries surveyed with a Muslim majority population, whose citizens tend to identify more with their nationality than their religion.[104] According Article 29 of Indonesia's Constitution however affirms that “the state is based on the belief in the one supreme God.”[e] Over the past 50 years, many Islamic groups have opposed this secular and pluralist direction, and sporadically have sought to establish an Islamic state. However, the country's mainstream Muslim community, including influential social organisations such as Muhammadiyah and NU, reject the idea. Proponents of an Islamic state argued unsuccessfully in 1945 and throughout the parliamentary democracy period of the 1950s for the inclusion of language (the "Jakarta Charter") in the Constitution's preamble making it obligatory for Muslims to follow shari'a.  An Republic throughout the 1950s. The outbreak of the Islamic state in multiple provinces, started in West Java led by Kartosoewirjo, the rebellion also spread to Central Java, South Sulawesi and Aceh. The Islamist armed rebellion was successfully cracked down in 1962. The movement has alarmed the Sukarno administration to the potential threat of political Islam against the Indonesian Republic.[105]

During the Suharto regime (1966–1998), the government prohibited all advocacy of an Islamic state. This timeframe also coincided with an increase in the number of Liberal Muslims in Indonesia from 1970 until 2005.[106] However, with the loosening of restrictions on freedom of speech and religion that followed Suharto's fall in 1998, proponents of the "Jakarta Charter" resumed advocacy efforts. This proved the case before the 2002 Annual Session of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR), a body that has the power to change the Constitution. The nationalist political parties, regional representatives elected by provincial legislatures, and appointed police, military, and functional representatives, who together held a majority of seats in the MPR, rejected proposals to amend the Constitution to include shari'a, and the measure never came to a formal vote. The MPR approved changes to the Constitution that mandated that the Government increase "faith and piety" in education. This decision, seen as a compromise to satisfy Islamist parties, set the scene for a controversial education bill signed into law in July 2003. [citation needed ]

On 9 May 2017, Indonesian politician Basuki Tjahaja Purnama was sentenced to two years in prison by the North Jakarta District Court after being found guilty of committing blasphemy.[107] The case later led to a growth in the movement against electing non-Islamic leaders, with 59 percent of Indonesian people not wanting to elect non-Muslim leaders as of 2018.[108] It also contributed in increasing number of identity politics in Indonesia as carried out by Anies Baswedan in 2017, which he referred as inevitable because identity is always related as a nature of the candidate.[109][110] Shari'a in Aceh Shari'a generated debate and concern during 2004, and many of the issues raised touched on religious freedom. Aceh remained the only part of the country where the central Government specifically authorised shari'a. Law 18/2001 granted Aceh special autonomy and included authority for Aceh to establish a system of shari'a as an adjunct to, not a replacement for, national civil and criminal law. Before it could take effect, the law required the provincial legislature to approve local regulations ("qanun") incorporating shari'a precepts into the legal code. Law 18/2001 states that the shari'a courts would be "free from outside influence by any side." Article 25(3) states that the authority of the court will only apply to Muslims. Article 26(2) names the national Supreme Court as the court of appeal for Aceh's shari'a courts.[citation needed] Aceh is the only province that has shari'a courts. Religious leaders responsible for drafting and implementing the shari'a regulations stated that they had no plans to apply criminal sanctions for violations of shari'a. Islamic law in Aceh, they said, would not provide for strict enforcement of fiqh or hudud, but rather would codify traditional Acehnese Islamic practice and values such as discipline, honesty, and proper behaviour. They claimed enforcement would not depend on the police but rather on public education and societal consensus. Because Muslims make up the overwhelming majority of Aceh's population, the public largely accepted shari'a, which in most cases merely regularised common social practices. For example, a majority of women in Aceh already covered their heads in public. Provincial and district governments established shari'a bureaus to handle public education about the new system, and local Islamic leaders, especially in North Aceh and Pidie, called for greater government promotion of shari'a as a way to address mounting social ills. The imposition of martial law in Aceh in May 2003 had little impact on the implementation of shari'a. The Martial Law Administration actively promoted shari'a as a positive step toward social reconstruction and reconciliation. Some human rights and women's rights activists complained that implementation of shari'a focused on superficial issues, such as proper Islamic dress, while ignoring deep-seated moral and social problems, such as corruption. AhmadiyyaIn 1980 the MUI) issued a "fatwa" (a legal opinion or decree issued by an Islamic religious leader) declaring that the Ahmadis are not a legitimate form of Islam.[citation needed] In the past, mosques and other facilities belonging to Ahmadis had been damaged by offended Muslims in Indonesia; more recently, rallies have been held demanding that the sect be banned and some religious clerics have demanded Ahmadis be killed.[111][112]

Youth radicalizationSince the mid-2010s there has been a trend of radicalization among the youth, and a nationally representative survey done in 2019 by Alvara found out that around 60% of the generation Z (aged 14–21) and millennials (aged 22–29) identified as "puritan & ultraconservative". Observers link it to the influence of the Wahhabist Hijrah movement, something that the Indonesian government wants to curb as it feels it threatens the country's secular values and unity.[113] See also

Notes

References

Further readingWikimedia Commons has media related to Islam in Indonesia. Wikiquote has quotations related to Islam in Indonesia.

|