Romania in the Early Middle Ages

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

The Early Middle Ages in Romania started with the withdrawal of the

The

The nomadic

Banat, Crişana, and Transylvania were integrated into the

Background

Roman provinces and native tribes

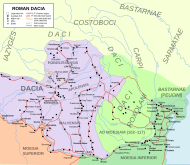

Contacts between the Roman Empire – which developed into the largest empire in the history of Europe – [1]and the natives of the regions now forming Romania commenced in the 2nd century BC.[2] These regions were inhabited by Dacians, Bastarnae and other peoples[3] whose incursions posed a threat to the empire.[4] The Romans initially attempted to secure their frontiers by various means, including the creation of buffer zones.[4] Finally, they decided that the annexation of the lands of these fierce "barbarians" was the best measure.[5] The territory of the Getae between the river Danube and the Black Sea (modern Dobruja) was the first region to be incorporated into the empire.[6] It was attached to the Roman province of Moesia in 46 AD.[6]

The Lower Danube marked the boundary between the empire and "Barbaricum"

Dacia was situated over the empire's natural borders.

Origin of the Romanians

Romanians speak a language originating from the dialects of the Roman provinces north of the "

Grigore Nandris writes that the

The Romanian religious vocabulary is also divided, with a small number of basic terms preserved from Latin[36] and a significant number of borrowings from Old Church Slavonic.[39] Romanian did not preserve Latin words connected to urbanized society.[40]

The Romanians'

Late Roman Age

Scythia Minor and the limes on the Lower Danube (c. 270–c. 700)

The territory between the Lower Danube and the Black Sea remained a fully integrated part of the Roman Empire, even after the abandonment of Trajan's Dacia.

The existence of Christian communities in Scythia Minor became evident under Emperor

The Huns destroyed Drobeta and Sucidava in the 440s, but the forts were restored under Emperor

North of the limes (c. 270–c. 330)

Transylvania and northern Banat, which had belonged to Dacia province, had no direct contact with the Roman Empire from the 270s.

Urns found in late 3rd-century cemeteries at

Gutthiuda: land of the Goths (c. 290–c. 455)

The Goths started penetrating into territories west of the river Dniester from the 230s.[74][75] Two distinct groups separated by the river, the Thervingi and the Greuthungi, quickly emerged among them.[76] The one-time province of Dacia was held by "the Taifali, Victohali, and Thervingi"[77] around 350.[19][78]

The Goths' success is marked by the expansion of the multiethnic "

The multiethnic Gutthiuda was divided into smaller political units or kuni, each headed by tribal chiefs or reiks.

Gothic dominance collapsed when the Huns arrived[94] and attacked the Thervingi in 376.[95] Most of the Thervingi sought asylum in the Roman Empire,[96] and were followed by large groups of Greuthungi and Taifali.[73] All the same, significant groups of Goths stayed in the territories north of the Danube.[97] For instance, Athanaric "retired with all his men to Caucalanda"—probably to the valley of the river Olt— from where they "drove out the Sarmatians".[98][99] A hoard of Roman coins issued under Valentinian I and Valens suggests that the gates of the amphitheatre at Ulpia Traiana were blocked around the same time.[100] The Pietroasele Treasure which was hidden around 450 also implies the presence of a Gothic tribal or religious leader in the lands between the Carpathians and the Lower Danube.[101] It contains a torc bearing the inscription GUTANI O WI HAILAG, which is interpreted by Malcolm Todd as "God who protects the Goths, most holy and inviolate".[102]

Gepidia: land of the Gepids (c. 290–c. 630)

The earliest reference to Gepids – an

The Huns imposed their authority over the Gepids by the 420s,

Three

New settlements appearing along the rivers Mureş,

The Avar invasion of 568 ended the independent Gepidia.[123] Written sources evidence the survival of Gepid groups within the Avar Empire.[124] For instance, Eastern Roman troops "encountered three Gepid settlements"[125] on the Tisa plains in 599 or 600.[126][124]

Hunnic Empire (c. 400–c. 460)

The Huns, a people of uncertain origin,

The Eastern Roman government paid an annual tribute to the Huns from the 420s.

The Huns imposed their authority on a sedentary population.[139] Priscus of Panium refers to a village where he and his retinue were supplied "with millet instead of corn" and "medos (mead) instead of wine".[138][140] Attila's sudden death in 453[141] caused a civil war among his sons.[142] The subject peoples revolted and emerged the victors at the Battle of Nedao in 454.[111][143] The remnants of the Huns withdrew to the Pontic steppes.[144] One of their groups was admitted to settle in Scythia Minor in 460.[145]

After the first migrations

Between Huns and Avars (c. 450–c. 565)

The last "Sântana de Mureş-Chernyakhov" objects once widespread in Gutthiuda – such as fine wares and weapons – are dated to the period ending around 430.

There are few known cemeteries from the second half of the 5th century,

Jordanes,

The names of early 6th-century leaders of the Sclavenes or Antes are unknown.

The disappearance of bronze and gold coins from sites north of the Lower Danube demonstrates an "economic closure of the frontier" of the Eastern Roman Empire between 545 and 565.

Avar Empire (c. 565–c. 800)

The

Graves of males interred together with horses found at

Large "

Emergence of new powers (c. 600–c. 895)

The Lower Danube region experienced a period of stability after the establishment of the Avar Empire.

Villages of sunken huts with stone ovens[149] appeared in Transylvania around 600.[197][198][199] Their network was expanding along the rivers Mureş, Olt and Someş.[197][198] The so-called "Mediaş group" of cremation or mixed cemeteries emerged in this period near salt mines.[200] The Hungarian and the Romanian vocabulary of salt mining was taken from Slavic, suggesting that Slavs were employed in the mines for centuries.[201][202] Bistriţa ("swift"), Crasna ("nice" or "red"), Sibiu ("dogwood"), and many other rivers and settlements with names of Slavic origin also evidence the presence of Slavs in Transylvania.[203][204]

The Turkic-speaking Bulgars arrived in the territories west of the river Dniester around 670.

Opreanu writes that the "new cultural synthesis" known as the "

"Dridu" communities produced and used gray or yellow fine pottery,

Contemporaneous authors rarely dwelled on early medieval Southeastern Europe.

In the same year, the nomadic Hungarians – who had arrived in the Lower Danube region from the

About 300 years later,

Formation of new states and the last waves of migrations

First Bulgarian Empire after conversion (864–1018)

Traces of Bulgarian influence in the territory of modern Romania are found mostly in the area of Wallachia. For example in sites from

Byzantine troops occupied large portions of Bulgaria, including modern

Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin (c. 895–c. 1000)

The way taken by the Hungarians across the

Emperor

Patzinakia: land of the Pechenegs (c. 895–c. 1120)

The Turkic-speaking[243] Pechenegs took the control of the territories east of the Carpathians from the Hungarians around 895.[287][288] Emperor Constantine VII wrote that two Pecheneg "provinces" or "clans" ("Kato Gyla" and "Giazichopon")[289] were located in Moldavia and Wallachia around 950.[290] The change of dominion had no major effect on the sedentary "Dridu"[291] villages in the region.[292] The settlements in Moldavia and Wallachia, most of them built on river banks or lake shores, remained unfortified.[293] Sporadic finds of horse brasses and other "nomadic" objects evidence the presence of Pechenegs in "Dridu" communities.[294] Snaffle bits with rigid mouthpieces and round stirrups—novelties of the early 10th century—were also unearthed in Moldavia and Wallachia.[295] Cemeteries of the locals show that inhumation replaced cremation by the end of the 10th century.[296]

The

Large groups of Pechenegs pressured from the east by the

Byzantine revival and the Second Bulgarian Empire (970s–c. 1185)

Around 971, Emperor

Kingdom of Hungary (c. 1000–1241)

Royal administration in the entire kingdom was based on

Eastward expansion of "Bijelo Brdo" villages along the Mureş continued in the 11th century.

The early presence of Székelys at

A great number of

The earliest royal charter referring to Romanians in Transylvania is connected to the foundation of the Cistercian abbey at Cârța around 1202,[346] which was granted land, up to that time possessed by Romanians.[347] Another royal charter reveals that Romanians fought for Bulgaria along with Saxons, Székelys and Pechenegs under the leadership of the Count of Sibiu in 1210.[348] The Orthodox Romanians remained exempt from the tithe payable by all Catholic peasants to the Church.[349] Furthermore, they only paid a special in kind tax, the "fiftieth" on their herds.[349]

Organized settling continued with the arrival of the

Cumania: land of the Cumans (c. 1060–1241)

The arrival of the

A coalition of

Mongol invasion (1241–1242)

The

The Mongol invasion lasted for a year, and the Mongols devastated huge swathes of territory of the kingdom before their unexpected withdrawal in 1242.

After the devastation of the region, they [the Mongols] surrounded the great village with a combined force of some Tatars together with Russians, Cumans and their Hungarian prisoners. They sent first the Hungarian prisoners ahead and when they were all slain, the Russians, the Ishmaelites, and Cumans went into battle. The Tatars, standing behind them all at the back, laughed at their plight and ruin and killed those who retreated from the battle and subjected as many as they could to their devouring swords, so that after fighting for a week, day and night, and filling up the moat, they captured the village. Then they made the soldiers and ladies, of whom there were many, stand in a field on one side and the peasants on the other. Having robbed them of their money, clothing and other goods, they cruelly executed them with axes and swords, leaving only some of the ladies and girls alive, whom they took for their entertainment.

— Master Roger's Epistle[380]

Aftermath

A new period of intensive settlements began in Banat, Transylvania and other regions within the Kingdom of Hungary after the withdrawal of the Mongols.

Internal conflicts characterized the last decades of the 13th century in the Kingdom of Hungary.[383] For instance, a feud between King Béla and his son, Stephen caused a civil war which lasted from 1261 to 1266.[384] Taking advantage of the emerging anarchy, Voivode Litovoi attempted to get rid of the Hungarian monarchs' suzerainty in the 1270s, but he fell in a battle while fighting against royal troops.[385][386] One of his successors, Basarab I of Wallachia was the first Romanian monarch whose sovereignty was internationally recognized after his victory over King Charles I of Hungary in the Battle of Posada of 1330.[386]

See also

- Balkan–Danubian culture

- Banat in the Middle Ages

- Bulgarian lands across the Danube

- History of the Székely people

Footnotes

- ^ Heather 2006, p. xi.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b Opreanu 2005, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 60.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, pp. 60, 67.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 4.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 87.

- ^ Haynes & Hanson 2004, pp. 12, 19–21.

- ^ Eutropius: Breviarium (8.6.), p. 50.

- ^ a b Georgescu 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Haynes & Hanson 2004, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 102.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Tóth 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c Heather 2010, p. 112.

- ^ Tóth 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Eutropius: Breviarium (9.15.), p. 59.

- ^ Tóth 1994, pp. 55–56.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 163.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Hall 1974, p. 70.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 13.

- ^ Vékony 2000, pp. 206–207.

- ^ The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor (258.10-21.), p. 381.

- ^ a b Opreanu 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Nandris 1951, p. 13.

- ^ Mallinson 1998, p. 413.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Kopecký, Peter (2004–2005), "Caractéristique lexicale de l'élément slave dans le vocabulaire roumain: Confrontation historique aux sédiments lexicaux turcs et grecs [=Lexical characteristics of the Slavic elements of the Romanians language: A historical comparison with the Turkic and Greek lexical layers]" (PDF), Ianua: Revista Philologica Romanica, 5: 43–53, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-05

- ^ Petrucci 1999, pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b Nandris 1951, p. 12.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 224.

- ^ Petrucci 1999, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 202.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, pp. 8, 13.

- ^ a b Georgescu 1991, p. 14.

- ^ a b Vékony 2000, p. 209.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, pp. 110–111.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 55–56, 221.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c Bărbulescu 2005, p. 185.

- ^ Curta 2005, p. 178.

- ^ Ellis 1998, pp. 231–232.

- ^ a b Opreanu 2005, p. 115.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 33.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 165, 221.

- ^ a b c Wolfram 1988, p. 61.

- ^ Heather 2010, pp. 72, 75.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (27.5.), p. 337.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 165–166, 222.

- ^ Teodor 2005, pp. 216, 223–224.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 54–55, 64–65.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 166, 222.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 178, 222.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, p. 181.

- ^ a b Haynes & Hanson 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, p. 183.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Haynes & Hanson 2004, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 65.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Zosimus (2002), The History, retrieved 18 July 2012

- ^ Heather 2010, pp. 166, 660.

- ^ Thompson 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Heather 2006, p. 330.

- ^ a b Heather 2010, p. 151.

- ^ Heather 2010, pp. 112, 117.

- ^ Todd 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Eutropius: Breviarium (8.2.), p. 48.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 67.

- ^ Heather & Matthews 1991, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Heather & Matthews 1991, pp. 64, 79.

- ^ Ellis 1998, p. 230.

- ^ Heather & Matthews 1991, pp. 65, 79.

- ^ Curta 2005, pp. 188–191.

- ^ a b Heather & Matthews 1991, p. 53.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Heather & Matthews 1991, p. 54.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 94, 96.

- ^ Ambrose: On the Holy Spirit (Preface 17), retrieved 23 July 2013

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 94, 416.

- ^ a b Todd 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Philostorgius: Church History (2.5.), p. 20.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 75–78.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 75.

- ^ Thompson 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Todd 2003, p. 164.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, p. 73.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (31.4.), p. 418.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, p. 182.

- ^ Todd 2003, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Todd 2003, p. 126.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, pp. 57–59, 246, 401.

- ^ Genethliacus of Maximian Augustus, p. 76.

- ^ Genethliacus of Maximian Augustus, p. 100.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, pp. 190–191.

- ^ a b Bóna 1994, p. 77.

- ^ Todd 2003, p. 220.

- ^ Todd 2003, pp. 220, 223.

- ^ a b Heather 2006, p. 354.

- ^ a b Todd 2003, p. 223.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 224.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 80.

- ^ The Gothic History of Jordanes (50:264), p. 126.

- ^ Bărbulescu 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 84.

- ^ Curta 2008, pp. 87, 205.

- ^ a b Bóna 1994, pp. 86, 89.

- ^ Bóna 1994, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 194.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 195, 201.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 63.

- ^ a b Todd 2003, p. 221.

- ^ The History of Theophylact Simocatta (viii. 3.11.), p. 213.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 62.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, p. 123.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (31.2.), p. 412.

- ^ Thompson 2001, pp. 47, 50.

- ^ Thompson 2001, pp. 30, 40–41.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Heather 2006, p. 196.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, p. 126.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b Heather 2006, p. 329.

- ^ Heather 2006, pp. 325–329, 485.

- ^ a b Bury, J. B., Priscus at the court of Attila, retrieved 15 July 2012

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 177.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, p. 131.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 143.

- ^ Heather 2006, pp. 353–354.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 144.

- ^ Heather 2006, p. 356.

- ^ Heather 2006, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 200.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Teodor 1980, p. 19.

- ^ a b Curta 2001, p. 285.

- ^ Teodor 1980, p. 7.

- ^ Barford 2001, p. 48.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Teodor 2005, pp. 216–222.

- ^ a b Teodor 2005, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b Teodor 1980, p. 11.

- ^ Barford 2001, pp. 201, 402.

- ^ Teodor 2005, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Barford 2001, p. 202.

- ^ Curta 2008, p. 201.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 81, 115.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Barford 2001, p. 58.

- ^ Maurice's Strategikon (11.4.4-5), p. 120.

- ^ Curta 2005, p. 184.

- ^ Curta 2005, p. 332.

- ^ Procopius: History of the Wars (7.14.22.), p. 269.

- ^ Procopius: History of the Wars (7.14.33.), p. 275.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 79–80, 331–332.

- ^ Curta 2005, pp. 186, 196.

- ^ Barford 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 309.

- ^ Curta 2008, pp. 185, 309.

- ^ Curta 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 295–297, 309.

- ^ Heather 2010, pp. 213, 401.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Urbańczyk 2005, p. 144.

- ^ a b Bóna 1994, p. 93.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 65.

- ^ Barford 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Barford 2001, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 101.

- ^ The History of Theophylact Simocatta (vi. 9.1.), p. 172.

- ^ a b Madgearu 2005a, pp. 103, 117.

- ^ Barford 2001, pp. 79, 84.

- ^ Madgearu 2005a, p. 106.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 92.

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 78.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 52.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 291.

- ^ Teodor 1980, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Bóna 1994, pp. 98–99.

- ^ The Geography of Ananias of Şirak (L1881.3.9), p. 48.

- ^ a b c Bărbulescu 2005, p. 197.

- ^ a b Bóna 1994, p. 99.

- ^ a b Barford 2001, p. 76.

- ^ Madgearu 2005a, pp. 105, 119.

- ^ Madgearu 2005a, p. 104.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 98.

- ^ Kristó 2003, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 43.

- ^ Fiedler 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Fiedler 2008, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Fiedler 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 68.

- ^ Fiedler 2008, p. 157.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 69.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 50, 87.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Fiedler 2008, p. 200.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Teodor 1980, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 236.

- ^ Teodor 1980, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Opreanu 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Fiedler 2008, p. 159.

- ^ Madgearu 2005b, p. 68.

- ^ a b Fiedler 2008, p. 161.

- ^ a b Madgearu 2005b, p. 134.

- ^ Bóna 1994, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 17–20.

- ^ Royal Frankish Annals (year 824), p. 116.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 157.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 149.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 99.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 56.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 57.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 154, 156–157, 159.

- ^ a b c d Curta 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Madgearu 2005b, p. 132.

- ^ Annals of Fulda (year 892), p. 124.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 59.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 58, 64.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 145.

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 138.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d Engel 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Madgearu 2005b, p. 39.

- ^ a b Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 11.), p. 33.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 50.), p. 109.

- ^ Macartney 1953, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Sălăgean 2005, p. 141.

- ^ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 44.), p. 97.

- ^ a b Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 24.), p. 59.

- ^ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 25.), p. 61.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 142.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 452.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 143.

- ISBN 978-90-04-51586-4.

- ^ a b Stephenson 2000, pp. 51–58.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 187–189.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 152.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Sălăgean 2005, p. 146.

- ^ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Georgescu 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 27.), p. 65.

- ^ Madgearu 2005b, p. 92.

- ^ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 28), p. 98.

- ^ a b Bóna 1994, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Kristó 2003, p. 52.

- ^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 40), p. 177.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 190.

- ^ Kristó 2003, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Vistai, András János, Tekintő: Erdélyi helynévkönyv, Második kötet, I–P (""Tekintő": Book on Transylvanian Toponymy, Volume II, I–P ") (PDF), retrieved 22 July 2012

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 118.

- ^ Kristó 2003, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 90.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 180, 183.

- ^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 37), p. 169.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 120.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 200.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 186.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Eymund's Saga (ch. 8.), pp. 79–80.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 105, 125.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 303.

- ^ Jesch 2001, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Jesch 2001, p. 258.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Spinei 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 187.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, p. 57.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (10.3.), p. 299.

- ^ Vékony 2000, p. 212.

- ^ Vékony 2000, p. 215.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 168.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. xv.

- ^ a b Vékony 2000, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 248–250.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Hartwick, Life of King Stephen of Hungary (8), p. 383.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 432.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 355.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Kristó 2003, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Bóna 1994, p. 169.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 99.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 100.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 250–252.

- ^ Bóna 1994, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 250–251, 351.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 133.

- ^ Kristó 2003, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 352.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 353.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 122.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 163.

- ^ a b Sălăgean 2005, p. 164.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 354.

- ^ a b Makkai 1994, p. 189.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 140.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 119.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Makkai 1994, p. 193.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 95.

- ^ a b Sălăgean 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 246.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 257.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, pp. 42–47.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 306.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus by John Kinnamos (6.3.261), p. 196.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 317.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 298.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 406.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 408.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 409.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c d Curta 2006, p. 410.

- ^ Master Roger's Epistle (ch. 20), p. 167.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 195.

- ^ a b The Successors of Genghis Khan (ch. 1.), p. 70.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 436–442.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 447.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 414.

- ^ Vistai, András János, Tekintő: Erdélyi helynévkönyv, Első kötet, A–H (""Tekintő": Book on Transylvanian Toponymy, Volume II, A–H ") (PDF), retrieved 27 July 2012

- ^ Kristó 2003, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Vistai, András János, Tekintő: Erdélyi helynévkönyv, Harmadik kötet, Q–Zs (""Tekintő": Book on Transylvanian Toponymy, Volume II, Q–Zs") (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2011, retrieved 27 July 2012

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 157.

- ^ Master Roger's Epistle (ch. 37), p. 213.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 2003.

- ^ a b Spinei 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, pp. 179–183.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 192.

- ^ a b Georgescu 1991, p. 17.

Sources

Primary sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (AD 354–378) (Selected and translated by Walter Hamilton, With an Introduction and Notes by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill) (2004). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044406-3.

- Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (Translated by E. R. A. Sewter) (1969). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044958-7.

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation b Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus by John Kinnamos (Translated by Charles M. Brand) (1976). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04080-6.

- Eymund's Saga (1989). In Vikings in Russia: Yngvar's Saga and Eymund's Saga (Translated and Introduced by Hermann Palsson and Paul Edwards). Edingburgh University Press. pp. 69–89. ISBN 0-85224-623-4.

- Eutropius: Breviarium (Translated with an introduction and commentary by H. W. Bird) (1993). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-208-3.

- Genethliacus of Maximian Augustus by an Anonymous Orator (291) (Translation and Notes by Rodgers) (1994). In: In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini (Introduction, Translation, and Historical Commentary with the Latin Text of R. A. B. Mynors by C. E. V. Nixon and Barbara Saylor Rodgers) (1994); University of California Press; ISBN 0-520-08326-1.

- Hartvic, Life of King Stephen of Hungary (Translated by Nora Berend) (2001). In: Head, Thomas (2001); Medieval Hagiography: An Anthology; Routledge; ISBN 0-415-93753-1.

- Master Roger's Epistle to the Sorrowful Lament upon the Destruction of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Tatars (Translated and Annotated by János M. Bak and Martyn Rady) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

- Maurice's Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy (Translated by George T. Dennis) (1984). University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1772-1.

- Philostorgius: Church History (Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Philip R. Amidon, S. J.) (2007). Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-215-2.

- Procopius: History of the Wars (Books VI.16–VII.35.) (With an English Translation by H. B. Dewing) (2006). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99191-5.

- Royal Frankish Annals (1972). In: Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories (Translated by Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers); The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 0-472-06186-0.

- The Annals of Fulda (Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II) (Translated and annotated by Timothy Reuter) (1992). Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3458-2.

- The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor: Byzantine and Near Eastern History, AD 284–813 (Translated with Introduction and Commentary by Cyril Mango and Roger Scott with the assistance of Geoffrey Greatrex) (2006). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822568-3.

- The Geography of Ananias of Širak (AŠXARHAC’OYC’): The Long and the Short Recensions (Introduction, Translation and Commentary by Robert H. Hewsen) (1992). Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. ISBN 3-88226-485-3.

- The Gothic History of Jordanes (in English Version with an Introduction and a Commentary by Charles Christopher Mierow, Ph.D., Instructor in Classics in Princeton University) (2006). Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889758-77-9.

- The History of Theophylact Simocatta (An English Translation with Introduction and Notes: Michael and Mary Whitby) (1986). Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822799-X.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

- The Successors of Genghis Khan (Translated from the Persian of Rashīd Al-Dīn by John Andrew Boyle) (1971). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03351-6.

Secondary sources

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.

- Bărbulescu, Mihai (2005). "From the Romans until the End of the First Millenium AD". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vol. I. (until 1541). Romanian Cultural Institute. pp. 137–198. ISBN 973-7784-04-9.

- Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Treptow, Kurt W.; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997). A History of Romania. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98091-0-3.

- Bóna, István (1994). "From Dacia to Transylvania: The Period of the Great Migrations (271–895); The Hungarian–Slav Period (895–1172)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 62–177. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curta, Florin (2005). "Frontier Ethnogenesis in Late Antiquity: The Danube, the Tervingi, and the Slavs". In Curta, Florin (ed.). Borders, Barriers, and Ethnogenesis: Frontiers in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Brepols. pp. 173–204. ISBN 2-503-51529-0.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curta, Florin (2008). "Before Cyril and Methodius: Christianity and Barbarians beyond the Sixth- and Seventh-Century Danube Frontier". In Curta, Florin (ed.). East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The University of Michigan Press. pp. 181–219. ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Ellis, L. (1998). "Terra deserta: population, politics, and the [de]colonization of Dacia". In Shennan, Stephen (ed.). Population and Demography (World Archaeology, Volume Thirty, Number Two). Routledge. pp. 220–237. ISSN 0043-8243.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Fiedler, Uwe (2008). "Bulgars in the Lower Danube region: A survey of the archaeological evidence and of the state of current research". In Curta, Florin; Kovalev, Roman (eds.). The Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars, and Cumans. Brill. pp. 151–236. ISBN 978-90-04-16389-8.

- Fine, John V. A (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Hall, Robert A. Jr. (1974). External History of the Romance Languages. American Elsevier Publishing Company. ISBN 0-444-00136-0.

- Haynes, I. P.; Hanson, W. S. (2004). "An introduction to Roman Dacia". In Haynes, I. P.; Hanson, W. S. (eds.). Roman Dacia: The Making of a Provincial Society (Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, Number 56). Journal of Roman Archaeology, L.L.C. pp. 11–31. ISBN 1-887829-56-3.

- Heather, Peter; Matthews, John (1991). The Goths in the Fourth Century (Translated Texts for Historians, Volume 11). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-426-5.

- Heather, Peter (2006). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515954-7.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973560-0.

- Jesch, Judith (2001). Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-826-6.

- Kristó, Gyula (2003). Early Transylvania (895-1324). Lucidus Kiadó. ISBN 963-9465-12-7.

- Macartney, C. A. (1953). The Medieval Hungarian Historians: A Critical & Analytical Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08051-4.

- MacKendrick, Paul (1975). The Dacian Stones Speak. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1226-9.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005a). "Salt Trade and Warfare: The Rise of Romanian-Slavic Military Organization in Early Medieval Transylvania". In Curta, Florin (ed.). East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The University of Michigan Press. pp. 103–120. ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005b). The Romanians in the Anonymous Gesta Hungarorum: Truth and Fiction. Romanian Cultural Institute, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 973-7784-01-4.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture (Edited by Max Knight). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01596-7.

- Makkai, László (1994). "The Emergence of the Estates (1172–1526)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 178–243. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- Mallinson, Graham (1998). "Rumanian". In Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (eds.). The Romance Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 391–419. ISBN 0-19-520829-3.

- Nandris, Grigore (December 1951). "The Development and Structure of Rumanian". The Slavonic and East European Review. 30 (74). London: Modern Humanities Research Association & University College of London (School of Slavonic and East European Studies): 7–39.

- Opreanu, Coriolan Horaţiu (2005). "The North-Danube Regions from the Roman Province of Dacia to the Emergence of the Romanian Language (2nd–8th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 59–132. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Orel, Vladimir (1998). Albanian Etymological Dictionary. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11024-0.

- Petrucci, Peter R. (1999). Slavic Features in the History of Rumanian. LINCOM EUROPA. ISBN 3-89586-599-0.

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2005). "Romanian Society in the Early Middle Ages (9th–14th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 133–207. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Spinei, Victor (2003). The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies) and Museum of Brăila Istros Publishing House. ISBN 973-85894-5-2.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02756-4.

- Teodor, Dan Gh. (1980). The East Carpathian Area of Romania in the V-XI Centuries A.D. (BAR International Series 81). B. A. R. ISBN 0-86054-090-1.

- Teodor, Eugen S. (2005). "The Shadow of a Frontier: The Wallachian Plain during the Justinian Age". In Curta, Florin (ed.). Borders, Barriers, and Ethnogenesis: Frontiers in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Brepols. pp. 205–245. ISBN 2-503-51529-0.

- Thompson, E. A. (2001). The Huns. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-15899-5.

- Todd, Malcolm (2003). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-631-16397-2.

- Tóth, Endre (1994). "The Roman Province of Dacia". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 28–61. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Treptow, Kurt W.; Popa, Marcel (1996). Historical Dictionary of Romania. Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-3179-1.

- Urbańczyk, Przemysław (2005). "Early State Formation in East Central Europe". In Curta, Florin (ed.). East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The University of Michigan Press. pp. 139–151. ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83756-1.

- Vékony, Gábor (2000). Dacians, Romans, Romanians. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-13-4.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1988). History of the Goths. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06983-8.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. ISBN 0-520-08511-6.

Further reading

- Brezeanu, Stelian (2001). History and Imperial Propaganda in Rome during the 4th Century a. Chr, A Case Study: the Abandonment of Dacia. In: Annuario 3; Istituto Romano di cultura e ricerca umanistica.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel (1999). Romanians and Romania: A Brief History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-88033-440-1.

- (in French) Durandin, Catherine (1995). Historie des Roumains [=History of the Romanians]. Librairie Artheme Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-59425-5.

- (in Romanian) Madgearu, Alexandru (2008). Istoria Militară a Daciei Post Romane, 275–376 [=Military History of Post-Roman Dacia, 275–376]. Editura Cetatea de Scaun. ISBN 978-973-8966-70-3.