User:Damoose95/sandbox

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| It has been suggested that this page be merged into Perception. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2022. |

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Perception (from the Latin perceptio) is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment.[2]

All perception involves signals that go through the

Perception is not only the passive receipt of these signals, but it's also shaped by the recipient's learning, memory, expectation, and attention.[4][5] Sensory input is a process that transforms this low-level information to higher-level information (e.g., extracts shapes for object recognition).[5] The process that follows connects a person's concepts and expectations (or knowledge), restorative and selective mechanisms (such as attention) that influence perception.

Perception depends on complex functions of the nervous system, but subjectively seems mostly effortless because this processing happens outside conscious awareness.[3]

Since the rise of experimental psychology in the 19th century, psychology's understanding of perception has progressed by combining a variety of techniques.[4] Psychophysics quantitatively describes the relationships between the physical qualities of the sensory input and perception.[6] Sensory neuroscience studies the neural mechanisms underlying perception. Perceptual systems can also be studied computationally, in terms of the information they process. Perceptual issues in philosophy include the extent to which sensory qualities such as sound, smell or color exist in objective reality rather than in the mind of the perceiver.[4]

Although the senses were traditionally viewed as passive receptors, the study of illusions and ambiguous images has demonstrated that the brain's perceptual systems actively and pre-consciously attempt to make sense of their input.[4] There is still active debate about the extent to which perception is an active process of hypothesis testing, analogous to science, or whether realistic sensory information is rich enough to make this process unnecessary.[4]

The

"Percept" is also a term used by

Process and terminology

The process of perception begins with an object in the real world, known as the

To explain the process of perception, an example could be an ordinary shoe. The shoe itself is the distal stimulus. When light from the shoe enters a person's eye and stimulates the retina, that stimulation is the proximal stimulus.[11] The image of the shoe reconstructed by the brain of the person is the percept. Another example could be a ringing telephone. The ringing of the phone is the distal stimulus. The sound stimulating a person's auditory receptors is the proximal stimulus. The brain's interpretation of this as the "ringing of a telephone" is the percept.

The different kinds of sensation (such as warmth, sound, and taste) are called sensory modalities or stimulus modalities.[10][12]

Bruner's Model of the Perceptual Process

Psychologist Jerome Bruner developed a model of perception, in which people put "together the information contained in" a target and a situation to form "perceptions of ourselves and others based on social categories."[13] [14] This model is composed of three states:

- When we encounter an unfamiliar target, we are very open to the informational cues contained in the target and the situation surrounding it.

- The first stage doesn't give us enough information on which to base perceptions of the target, so we will actively seek out cues to resolve this ambiguity. Gradually, we collect some familiar cues that enable us to make a rough categorization of the target. (see also Social Identity Theory)

- The cues become less open and selective. We try to search for more cues that confirm the categorization of the target. We also actively ignore and even distort cues that violate our initial perceptions. Our perception becomes more selective and we finally paint a consistent picture of the target.

Saks & John's Three Components to Perception

According to Alan Saks and Gary Johns, there are three components to perception:[15]

- The Perceiver: a person whose awareness is focused on the stimulus, and thus begins to perceive it. There are many factors that may influence the perceptions of the perceiver, while the three major ones include (1) emotional state, and (3) experience. All of these factors, especially the first two, greatly contribute to how the person perceives a situation. Oftentimes, the perceiver may employ what is called a "perceptual defense," where the person will only "see what they want to see"—i.e., they will only perceives what they want to perceive even though the stimulus acts on his or her senses.

- The Target: the object of perception; something or someone who is being perceived. The amount of information gathered by the sensory organs of the perceiver affects the interpretation and understanding about the target.

- The Situation: the environmental factors, timing, and degree of stimulation that affect the process of perception. These factors may render a single stimulus to be left as merely a stimulus, not a percept that is subject for brain interpretation.

Multistable Perception

Stimuli are not necessarily translated into a percept and rarely does a single stimulus translate into a percept. An ambiguous stimulus may sometimes be transduced into one or more percepts, experienced randomly, one at a time, in a process termed "multistable perception." The same stimuli, or absence of them, may result in different percepts depending on subject's culture and previous experiences.

Ambiguous figures demonstrate that a single stimulus can result in more than one percept. For example, the Rubin vase can be interpreted either as a vase or as two faces. The percept can bind sensations from multiple senses into a whole. A picture of a talking person on a television screen, for example, is bound to the sound of speech from speakers to form a percept of a talking person.

Types of Perception

Vision

. Visual Perception has been continuous study since the ancient Greek schools. Aristotle, Isaac Newton Leonardo da Vinci have helped progress our knowledge and interest in the field of visual perception. Hermann von Helmholtz is one of the first to study visual perception in our modern era. He concluded that there is an unconscious inference that aids the visual system. The brain assumes visual perception based off incomplete data. The brain uses past experiences to aid it in this process. von Helmholtz, Hermann (1925). Handbuch der physiologischen Optik. 3. Leipzig: Voss. Visual Illusions and Gestalt psychology has also progressed how the brain makes inferences based off the information it has. Gestalt psychology took hold in the 1930s to 1940s and influenced vision theories today. Wagemans, Johan (November 2012). "A Century of Gestalt Psychology in Visual Perception". Psychological Bulletin. 138 (6): 1172–1217. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.8394. doi:10.1037/a0029333. PMC 3482144. PMID 22845751.

Sound

Hearing (or audition) is the ability to perceive sound by detecting vibrations (i.e., sonic detection). Frequencies capable of being heard by humans are called audio or audible frequencies, the range of which is typically considered to be between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz.[17] Frequencies higher than audio are referred to as ultrasonic, while frequencies below audio are referred to as infrasonic

The

Sound does not usually come from a single source: in real situations, sounds from multiple sources and directions are superimposed as they arrive at the ears. Hearing involves the computationally complex task of separating out sources of interest, identifying them and often estimating their distance and direction.[18]

Touch

Gibson defined the haptic system as "the sensibility of the individual to the world adjacent to his body by use of his body."[22] Gibson and others emphasized the close link between body movement and haptic perception, where the latter is active exploration.

The concept of haptic perception is related to the concept of extended physiological proprioception according to which, when using a tool such as a stick, perceptual experience is transparently transferred to the end of the tool.

Taste

Taste (formally known as gustation) is the ability to perceive the flavor of substances, including, but not limited to, food. Humans receive tastes through sensory organs concentrated on the upper surface of the tongue, called taste buds or gustatory calyculi.[23] The human tongue has 100 to 150 taste receptor cells on each of its roughly-ten thousand taste buds.[24]

Traditionally, there have been four primary tastes:

Smell

Smell is the process of absorbing molecules through olfactory organs, which are absorbed by humans through the nose. These molecules diffuse through a thick layer of mucus; come into contact with one of thousands of cilia that are projected from sensory neurons; and are then absorbed into a receptor (one of 347 or so).[30] It is this process that causes humans to understand the concept of smell from a physical standpoint.

Smell is also a very interactive sense as scientists have begun to observe that olfaction comes into contact with the other sense in unexpected ways.[31] It is also the most primal of the senses, as it is known to be the first indicator of safety or danger, therefore being the sense that drives the most basic of human survival skills. As such, it can be a catalyst for human behavior on a subconscious and instinctive level.[32]

Social

Social perception is the part of perception that allows people to understand the individuals and groups of their social world. Thus, it is an element of social cognition.[33]

Social interactions consist of Physical influences, Situations, and behaviors.

People are influence each other by physical attributes. This includes hair, weight, and height voice just to name a few physical influences. These physical attributes influence our first impressions and judgments that lead to our behaviors. Kassin, Saul; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose (2008). Social Psychology Seventh Edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. pp. 93–127. ISBN 978-0-618-86846-9.

In situations we take our past personal experiences and use them to influence the outcomes in the situations we are experiencing. These preset notions about events or behaviors tend to come from our cultural back ground, and how we are raised. Kassin, Saul; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose (2008). Social Psychology Seventh Edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. pp. 93–127. ISBN 978-0-618-86846-9. Nonverbal behaviors communicate our emotions and personality. The Leading nonverbal behavior is our facial expressions. It has been commonly found that these facial expressions are consistent across is cultures. Some of the other nonverbal behaviours are body language, eye contact and vocal intonations. Aronson, Elliot; Wilson, Timothy D.; Akert, Robin M. (2010). Social Psychology Seventh Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 83–115. ISBN 978-0-13-814478-4.

Speech

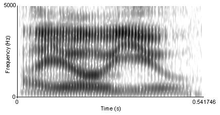

Speech perception is the process by which spoken language is heard, interpreted and understood. Research in this field seeks to understand how human listeners recognize the sound of speech (or phonetics) and use such information to understand spoken language.

Listeners manage to perceive words across a wide range of conditions, as the sound of a word can vary widely according to words that surround it and the

The process of perceiving speech begins at the level of the sound within the auditory signal and the process of

Speech perception is not necessarily uni-directional. Higher-level language processes connected with morphology, syntax, and/or semantics may also interact with basic speech perception processes to aid in recognition of speech sounds.[citation needed] It may be the case that it is not necessary (maybe not even possible) for a listener to recognize phonemes before recognizing higher units, such as words. In an experiment, Richard M. Warren replaced one phoneme of a word with a cough-like sound. His subjects restored the missing speech sound perceptually without any difficulty. Moreover, they were not able to accurately identify which phoneme had even been disturbed.[36]

Faces

Social touch

The somatosensory cortex is a part of the brain that receives and encodes sensory information from receptors of the entire body.[37]

Multi-Modal Perception

Time (Chronoception)

One or more

Agency

Sense of agency refers to the subjective feeling of having chosen a particular action. Some conditions, such as schizophrenia, can cause a loss of this sense, which may lead a person into delusions, such as feeling like a machine or like an outside source is controlling them. An opposite extreme can also occur, where people experience everything in their environment as though they had decided that it would happen.[43]

Even in non-pathological cases, there is a measurable difference between the making of a decision and the feeling of agency. Through methods such as the Libet experiment, a gap of half a second or more can be detected from the time when there are detectable neurological signs of a decision having been made to the time when the subject actually becomes conscious of the decision.

There are also experiments in which an illusion of agency is induced in psychologically normal subjects. In 1999, psychologists Wegner and Wheatley gave subjects instructions to move a mouse around a scene and point to an image about once every thirty seconds. However, a second person—acting as a test subject but actually a confederate—had their hand on the mouse at the same time, and controlled some of the movement. Experimenters were able to arrange for subjects to perceive certain "forced stops" as if they were their own choice.[44][45]

Familiarity

The

Recent studies on lesions in the area concluded that rats with a damaged perirhinal cortex were still more interested in exploring when novel objects were present, but seemed unable to tell novel objects from familiar ones—they examined both equally. Thus, other brain regions are involved with noticing unfamiliarity, while the perirhinal cortex is needed to associate the feeling with a specific source.[48]

Sexual stimulation

Other senses

Reality

In the case of visual perception, some people can actually see the percept shift in their

This confusing ambiguity of perception is exploited in human technologies such as

There is also evidence that the brain in some ways operates on a slight "delay" in order to allow nerve impulses from distant parts of the body to be integrated into simultaneous signals.[51]

Perception is one of the oldest fields in psychology. The oldest

Physiology

The receptive field is the specific part of the world to which a receptor organ and receptor cells respond. For instance, the part of the world an eye can see, is its receptive field; the light that each rod or cone can see, is its receptive field.[53] Receptive fields have been identified for the visual system, auditory system and somatosensory system, so far. Research attention is currently focused not only on external perception processes, but also to "interoception", considered as the process of receiving, accessing and appraising internal bodily signals. Maintaining desired physiological states is critical for an organism's well being and survival. Interoception is an iterative process, requiring the interplay between perception of body states and awareness of these states to generate proper self-regulation. Afferent sensory signals continuously interact with higher order cognitive representations of goals, history, and environment, shaping emotional experience and motivating regulatory behavior.[54]

Features

Constancy

Perceptual constancy is the ability of perceptual systems to recognize the same object from widely varying sensory inputs.[5]: 118–120 [55] For example, individual people can be recognized from views, such as frontal and profile, which form very different shapes on the retina. A coin looked at face-on makes a circular image on the retina, but when held at angle it makes an elliptical image.[18] In normal perception these are recognized as a single three-dimensional object. Without this correction process, an animal approaching from the distance would appear to gain in size.[56][57] One kind of perceptual constancy is color constancy: for example, a white piece of paper can be recognized as such under different colors and intensities of light.[57] Another example is roughness constancy: when a hand is drawn quickly across a surface, the touch nerves are stimulated more intensely. The brain compensates for this, so the speed of contact does not affect the perceived roughness.[57] Other constancies include melody, odor, brightness and words.[58] These constancies are not always total, but the variation in the percept is much less than the variation in the physical stimulus.[57] The perceptual systems of the brain achieve perceptual constancy in a variety of ways, each specialized for the kind of information being processed,[59] with phonemic restoration as a notable example from hearing.

Grouping (Gestalt)

The principles of grouping (or Gestalt laws of grouping) are a set of principles in

- Proximity: the principle of proximity states that, all else being equal, perception tends to group stimuli that are close together as part of the same object, and stimuli that are far apart as two separate objects.

- Similarity: the principle of similarity states that, all else being equal, perception lends itself to seeing stimuli that physically resemble each other as part of the same object and that are different as part of a separate object. This allows for people to distinguish between adjacent and overlapping objects based on their visual texture and resemblance.

- Closure: the principle of closure refers to the mind's tendency to see complete figures or forms even if a picture is incomplete, partially hidden by other objects, or if part of the information needed to make a complete picture in our minds is missing. For example, if part of a shape's border is missing people still tend to see the shape as completely enclosed by the border and ignore the gaps.

- Good Continuation: the principle of good continuation makes sense of stimuli that overlap: when there is an intersection between two or more objects, people tend to perceive each as a single uninterrupted object.

- Common Fate: the principle of common fate groups stimuli together on the basis of their movement. When visual elements are seen moving in the same direction at the same rate, perception associates the movement as part of the same stimulus. This allows people to make out moving objects even when other details, such as color or outline, are obscured.

- The principle of good form refers to the tendency to group together forms of similar shape, pattern, color, etc.[60][61][62][63]

Later research has identified additional grouping principles.[64]

Contrast effects

A common finding across many different kinds of perception is that the perceived qualities of an object can be affected by the qualities of context. If one object is extreme on some dimension, then neighboring objects are perceived as further away from that extreme.

"

The contrast effect was noted by the 17th Century philosopher

Theories

Perception as Direct Perception (Gibson)

Cognitive theories of perception assume there is a poverty of stimulus. This is the claim that sensations, by themselves, are unable to provide a unique description of the world.[71] Sensations require 'enriching', which is the role of the mental model.

The

Perception-in-Action

From Gibson's early work derived an ecological understanding of perception known as perception-in-action, which argues that perception is a requisite property of animate action. It posits that, without perception, action would be unguided, and without action, perception would serve no purpose. Animate actions require both perception and motion, which can be described as "two sides of the same coin, the coin is action." Gibson works from the assumption that singular entities, which he calls invariants, already exist in the real world and that all that the perception process does is home in upon them.

The

A mathematical theory of perception-in-action has been devised and investigated in many forms of controlled movement, and has been described in many different species of organism using the

Evolutionary Psychology (EP)

Many philosophers, such as Jerry Fodor, write that the purpose of perception is knowledge. However, evolutionary psychologists hold that the primary purpose of perception is to guide action.[77] They give the example of depth perception, which seems to have evolved not to help us know the distances to other objects but rather to help us move around in space.[77]

Evolutionary psychologists argue that animals ranging from fiddler crabs to humans use eyesight for collision avoidance, suggesting that vision is basically for directing action, not providing knowledge.[77] Neuropsychologists showed that perception systems evolved along the specifics of animals' activities. This explains why bats and worms can perceive different frequency of auditory and visual systems than, for example, humans.

Building and maintaining sense organs is

Scientists who study perception and sensation have long understood the human senses as adaptations.[77] Depth perception consists of processing over half a dozen visual cues, each of which is based on a regularity of the physical world.[77] Vision evolved to respond to the narrow range of electromagnetic energy that is plentiful and that does not pass through objects.[77] Sound waves provide useful information about the sources of and distances to objects, with larger animals making and hearing lower-frequency sounds and smaller animals making and hearing higher-frequency sounds.[77] Taste and smell respond to chemicals in the environment that were significant for fitness in the environment of evolutionary adaptedness.[77] The sense of touch is actually many senses, including pressure, heat, cold, tickle, and pain.[77] Pain, while unpleasant, is adaptive.[77] An important adaptation for senses is range shifting, by which the organism becomes temporarily more or less sensitive to sensation.[77] For example, one's eyes automatically adjust to dim or bright ambient light.[77] Sensory abilities of different organisms often co-evolve, as is the case with the hearing of echolocating bats and that of the moths that have evolved to respond to the sounds that the bats make.[77]

Evolutionary psychologists claim that perception demonstrates the principle of modularity, with specialized mechanisms handling particular perception tasks.[77] For example, people with damage to a particular part of the brain suffer from the specific defect of not being able to recognize faces (prosopagnosia).[77] EP suggests that this indicates a so-called face-reading module.[77]

Closed-loop perception

The theory of closed-loop perception proposes dynamic motor-sensory closed-loop process in which information flows through the environment and the brain in continuous loops.[78][79][80] [81]

Other theories of perception

- Feature Integration Theory (Anne Treisman)

- Empirical Theory of Perception

- Enactivism

- The Interactive Activation and Competition Model

- Recognition-By-Components Theory (Irving Biederman)

Effects on Perception

Effect of Experience

Past actions and events that transpire right before an encounter or any form of stimulation have a strong degree of influence on how sensory stimuli are processed and perceived. On a basic level, the information our senses receive is often ambiguous and incomplete. However, they are grouped together in order for us to be able to understand the physical world around us. But it is these various forms of stimulation, combined with our previous knowledge and experience that allows us to create our overall perception. For example, when engaging in conversation, we attempt to understand their message and words by not only paying attention to what we hear through our ears but also from the previous shapes we have seen our mouths make. Another example would be if we had a similar topic come up in another conversation, we would use our previous knowledge to guess the direction the conversation is headed in.[84]

Effect of motivation and expectation

A perceptual set, also called perceptual expectancy or just set is a predisposition to perceive things in a certain way.[85] It is an example of how perception can be shaped by "top-down" processes such as drives and expectations.[86] Perceptual sets occur in all the different senses.[56] They can be long term, such as a special sensitivity to hearing one's own name in a crowded room, or short term, as in the ease with which hungry people notice the smell of food.[87] A simple demonstration of the effect involved very brief presentations of non-words such as "sael". Subjects who were told to expect words about animals read it as "seal", but others who were expecting boat-related words read it as "sail".[87]

Sets can be created by motivation and so can result in people interpreting ambiguous figures so that they see what they want to see.[86] For instance, how someone perceives what unfolds during a sports game can be biased if they strongly support one of the teams.[88] In one experiment, students were allocated to pleasant or unpleasant tasks by a computer. They were told that either a number or a letter would flash on the screen to say whether they were going to taste an orange juice drink or an unpleasant-tasting health drink. In fact, an ambiguous figure was flashed on screen, which could either be read as the letter B or the number 13. When the letters were associated with the pleasant task, subjects were more likely to perceive a letter B, and when letters were associated with the unpleasant task they tended to perceive a number 13.[85]

Perceptual set has been demonstrated in many social contexts. People who are primed to think of someone as "warm" are more likely to perceive a variety of positive characteristics in them, than if the word "warm" is replaced by "cold".[citation needed] When someone has a reputation for being funny, an audience is more likely to find them amusing.[87] Individual's perceptual sets reflect their own personality traits. For example, people with an aggressive personality are quicker to correctly identify aggressive words or situations.[87]

One classic psychological experiment showed slower reaction times and less accurate answers when a deck of

Philosopher Andy Clark explains that perception, although it occurs quickly, is not simply a bottom-up process (where minute details are put together to form larger wholes). Instead, our brains use what he calls predictive coding. It starts with very broad constraints and expectations for the state of the world, and as expectations are met, it makes more detailed predictions (errors lead to new predictions, or learning processes). Clark says this research has various implications; not only can there be no completely "unbiased, unfiltered" perception, but this means that there is a great deal of feedback between perception and expectation (perceptual experiences often shape our beliefs, but those perceptions were based on existing beliefs).[90] Indeed, predictive coding provides an account where this type of feedback assists in stabilizing our inference-making process about the physical world, such as with perceptual constancy examples.

See also

- Action-specific perception

- Alice in Wonderland syndrome

- Apophenia

- Change blindness

- Generic views

- Ideasthesia

- Introspection

- Model-dependent realism

- Multisensory integration

- Near sets

- Neural correlates of consciousness

- Pareidolia

- Perceptual paradox

- Philosophy of perception

- Proprioception

- Qualia

- Recept

- Samjñā, the Buddhist concept of perception

- Simulated reality

- Simulation

- Visual routine

- Transsaccadic memory

- Binding Problem

References

Citations

- ^ "Soltani, A. A., Huang, H., Wu, J., Kulkarni, T. D., & Tenenbaum, J. B. Synthesizing 3D Shapes via Modeling Multi-View Depth Maps and Silhouettes With Deep Generative Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 1511-1519)". GitHub. 28 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel (2011). Psychology. Worth Publishers.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldstein (2009) pp. 5–7

- ^ a b c d e Gregory, Richard. "Perception" in Gregory, Zangwill (1987) pp. 598–601.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-495-90693-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Gustav Theodor Fechner. Elemente der Psychophysik. Leipzig 1860.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-932603-96-5. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Leibniz' Monadology

- ^ Deleuze and Guattari's What is Philosophy?

- ^ a b Pomerantz, James R. (2003): "Perception: Overview". In: Lynn Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, Vol. 3, London: Nature Publishing Group, pp. 527–537.

- ^ "Sensation and Perception". Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-306-48033-1. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Perception, Attribution, and, Judgment of Others" (PDF). Pearson Education. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Alan S. & Gary J. (2011). Perception, Attribution, and Judgment of Others. Organizational Behaviour: Understanding and Managing Life at Work, Vol. 7.

- ^ Sincero, Sarah Mae. 2013. "Perception." Explorable. Retrieved March 08, 2020 (https://explorable.com/perception).

- PMID 20152123.

- ^ "Frequency Range of Human Hearing". The Physics Factbook. Archived from the original on 21 September 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- S2CID 8898537.

- S2CID 3157751.

- S2CID 4413295.

- ISBN 978-0-313-23961-8.

- ^ Human biology (Page 201/464) Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Daniel D. Chiras. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2005.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-932603-96-5. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Umami Dearest: The mysterious fifth taste has officially infiltrated the food scene". trendcentral.com. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011.

- ^ "#8 Food Trend for 2010: I Want My Umami". foodchannel.com. 6 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-088397-4. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Food texture: measurement and perception (page 3–4/311) Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- ^ Why do two great tastes sometimes not taste great together? Archived 28 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine scientificamerican.com. Dr. Tim Jacob, Cardiff University. 22 May 2009.

- PMID 20603363.

- ^ Weir, Kirsten (February 2011). "Scents and sensibility". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Bergland, Christopher (29 June 2015). "Psychology Today". How Does Scent Drive Human Behavior?.

- ^ E. R. Smith, D. M. Mackie (2000). Social Psychology. Psychology Press, 2nd ed., p. 20

- ISBN 978-1-4419-5685-9. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ISBN 9780470756775.

- S2CID 30356740.

- ^ "Somatosensory Cortex". The Human Memory. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - PMID 27225773.

- ^ "Multi-Modal Perception". Lumen Waymaker. p. Introduction to Psychology. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - S2CID 3570715.

- ^ "Brain Areas Critical To Human Time Sense Identified". UniSci – Daily University Science News. 27 February 2001.

- PMID 24198770.

Manipulations of dopaminergic signaling profoundly influence interval timing, leading to the hypothesis that dopamine influences internal pacemaker, or "clock," activity. For instance, amphetamine, which increases concentrations of dopamine at the synaptic cleft advances the start of responding during interval timing, whereas antagonists of D2 type dopamine receptors typically slow timing;... Depletion of dopamine in healthy volunteers impairs timing, while amphetamine releases synaptic dopamine and speeds up timing.

- ISBN 978-0-465-04567-9.

- PMID 10424155.

- ^ Metzinger, Thomas (2003). Being No One. p. 508.

- .

- PMID 26424881.

- PMID 27398938.

- ^ Themes UF (29 March 2017). "Sensory Corpuscles". Abdominal Key. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ISBN 978-90-420-1035-2.

- ^ The Secret Advantage Of Being Short Archived 21 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Robert Krulwich. All Things Considered, NPR. 18 May 2009.

- S2CID 9546850.

- ^ Kolb & Whishaw: Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology (2003)

- PMID 26106345.

- ISBN 978-0-15-543689-3. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8220-5327-9. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-444-51750-0. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-86377-598-7. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7167-0617-5

- ISBN 978-0-87893-938-1. Archived from the originalon 23 July 2011.

- ^ Goldstein (2009). pp. 105–107

- ISBN 978-81-85880-28-0.

- ISBN 978-0-534-34014-8.

- ISBN 978-1-58391-328-4. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-549-91314-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-050477-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-59385-085-2. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-4419-6113-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- S2CID 16732916.

- ^ Stone, James V. (2012): "Vision and Brain: How we perceive the world", Cambridge, MIT Press, pp. 155-178.

- ^ Gibson, James J. (2002): "A Theory of Direct Visual Perception". In: Alva Noë/Evan Thompson (Eds.), Vision and Mind. Selected Readings in the Philosophy of Perception, Cambridge, MIT Press, pp. 77–89.

- ISBN 978-0521717663. Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2015.

- (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2013.

- ^ Consciousness in Action, S. L. Hurley, illustrated, Harvard University Press, 2002, 0674007964, pp. 430–432.

- ^ Glasersfeld, Ernst von (1995), Radical Constructivism: A Way of Knowing and Learning, London: RoutledgeFalmer; Poerksen, Bernhard (ed.) (2004), The Certainty of Uncertainty: Dialogues Introducing Constructivism, Exeter: Imprint Academic; Wright. Edmond (2005). Narrative, Perception, Language, and Faith, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-111529-3, Chapter 4, pp. 81–101.

- ^ Dewey, J. (1896) The reflex arc concept in psychology. Psychological Review 3:359-370

- ^ Friston, K. (2010) The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? nature reviews neuroscience 11:127-38

- ^ Tishby, N. and D. Polani, Information theory of decisions and actions, in Perception-Action Cycle. 2011, Springer. p. 601-636.

- ^ Ahissar, E. and E. Assa (2016) Perception as a closed-loop convergence process. eLife 5:e12830.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.12830

- ^ Sumner, Meghan. The Effect of Experience on the Perception and Representation of Dialect Variants (PDF). Elsevier Inc., 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - PMID 25278866.

- PMID 26582982.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-495-60197-5. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-495-59911-1. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-832821-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-86105-586-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "On the Perception of Incongruity: A Paradigm" by Jerome S. Bruner and Leo Postman. Journal of Personality, 18, pp. 206-223. 1949. Yorku.ca Archived 15 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Predictive Coding". Archived from the original on 5 December 2013.

Sources

Bibliography

- Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual Thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24226-5.

- Flanagan, J. R., & Lederman, S. J. (2001). "'Neurobiology: Feeling bumps and holes. News and Views", Nature, 412(6845):389–91. (PDF)

- Gibson, J. J. (1966). The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems, Houghton Mifflin.

- Gibson, J. J. (1987). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-89859-959-8

- Robles-De-La-Torre, G. (2006). "The Importance of the Sense of Touch in Virtual and Real Environments". IEEE Multimedia,13(3), Special issue on Haptic User Interfaces for Multimedia Systems, pp. 24–30. (PDF)

External links

Definitions from Wiktionary

Definitions from Wiktionary Media from Commons

Media from Commons News from Wikinews

News from Wikinews Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote Texts from Wikisource

Texts from Wikisource Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks Resources from Wikiversity

Resources from Wikiversity

- Theories of Perception Several different aspects on perception

- Richard L Gregory Theories of Richard. L. Gregory.

- Comprehensive set of optical illusions, presented by Michael Bach.

- Optical Illusions Examples of well-known optical illusions.

- The Epistemology of Perception Article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Cognitive Penetrability of Perception and Epistemic Justification Article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Articles and topics related to Perception | |

|---|---|

|