Ivermectin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌaɪvərˈmɛktɪn/, EYE-vər-MEK-tin |

| Trade names | Stromectol, Soolantra, Sklice, others |

| Other names | MK-933 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | |

| MedlinePlus | a607069 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

CYP450) | |

| Elimination half-life | 18 hours |

| Excretion | Feces; <1% urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol ) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Ivermectin is an

During the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation has been widely spread claiming that ivermectin is beneficial for treating and preventing COVID-19.[21][22] Such claims are not backed by credible scientific evidence.[23][24][25] Multiple major health organizations, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration,[26] the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[27] the European Medicines Agency,[28] and the World Health Organization have stated that ivermectin is not authorized or approved to treat COVID-19.[24][29]

Medical uses

Ivermectin is used to treat human diseases caused by

Worm infections

For

The

Mites and insects

Ivermectin is also used to treat infection with parasitic arthropods. Scabies – infestation with the mite Sarcoptes scabiei – is most commonly treated with topical permethrin or oral ivermectin. A single application of permethrin is more efficacious than a single treatment of ivermectin. For most scabies cases, ivermectin is used in a two dose regimen: a first dose kills the active mites, but not their eggs. Over the next week, the eggs hatch, and a second dose kills the newly hatched mites.[41][42] The two dose regimen of ivermectin has similar efficacy to the single dose permethrin treatment. Ivermectin is, however, more effective than permethrin when used in the mass treatment of endemic scabies.[43]

For severe "crusted scabies", where the parasite burden is orders of magnitude higher than usual, the U.S.

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindication to the use of ivermectin is hypersensitivity to the active ingredient or any component of the formulation.[48][49] In children under the age of five or those who weigh less than 15 kilograms (33 pounds),[50] there is limited data regarding the efficacy or safety of ivermectin, though the available data demonstrate few adverse effects.[51] However, the American Academy of Pediatrics cautions against use of ivermectin in such patients, as the blood-brain barrier is less developed, and thus there may be an increased risk of particular CNS side effects such as encephalopathy, ataxia, coma, or death.[52] The American Academy of Family Physicians also recommends against use in these patients, given a lack of sufficient data to prove drug safety.[53] Ivermectin is secreted in very low concentration in breast milk.[54] It remains unclear if ivermectin is safe during pregnancy.[55]

Adverse effects

Side effects, although uncommon, include fever, itching, and skin rash when taken by mouth;[10] and red eyes, dry skin, and burning skin when used topically for head lice.[56] It is unclear if the drug is safe for use during pregnancy, but it is probably acceptable for use during breastfeeding.[57]

Ivermectin is considered relatively free of toxicity in standard doses (around 300 µg/kg).

One concern is neurotoxicity after large overdoses, which in most mammalian species may manifest as central nervous system depression,[61] ataxia, coma, and even death,[62][63] as might be expected from potentiation of inhibitory chloride channels.[64]

Since drugs that inhibit the enzyme

During the course of a typical treatment, ivermectin can cause minor aminotransferase elevations. In rare cases it can cause mild clinically apparent liver disease.[66]

To provide context for the dosing and toxicity ranges, the LD50 of ivermectin in mice is 25 mg/kg (oral), and 80 mg/kg in dogs, corresponding to an approximated human-equivalent dose LD50 range of 2.02–43.24 mg/kg,[67] which is far in excess of its FDA-approved usage (a single dose of 0.150–0.200 mg/kg to be used for specific parasitic infections).[3] While ivermectin has also been studied for use in COVID-19, and while it has some ability to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro, achieving 50% inhibition in vitro was found to require an estimated oral dose of 7.0 mg/kg (or 35x the maximum FDA-approved dosage),[68] high enough to be considered ivermectin poisoning.[67] Despite insufficient data to show any safe and effective dosing regimen for ivermectin in COVID-19, doses have been taken far in excess of FDA-approved dosing, leading the CDC to issue a warning of overdose symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, decreased level of consciousness, confusion, blurred vision, visual hallucinations, loss of coordination and balance, seizures, coma, and death. The CDC advises against consuming doses intended for livestock or doses intended for external use and warns that increasing misuse of ivermectin-containing products is resulting in an increase in harmful overdoses.[69]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Ivermectin and its related drugs act by interfering with the nerve and muscle functions of

Pharmacokinetics

Ivermectin can be given by mouth, topically, or via injection. Oral doses are absorbed into systemic circulation; the alcoholic solution form is more orally available than tablet and capsule forms. Ivermectin is widely distributed in the body.[72]

Ivermectin does not readily cross the blood–brain barrier of mammals due to the presence of P-glycoprotein (the MDR1 gene mutation affects the function of this protein).[73] Crossing may still become significant if ivermectin is given at high doses, in which case brain levels peak 2–5 hours after administration. In contrast to mammals, ivermectin can cross the blood–brain barrier in tortoises, often with fatal consequences.[74]

Chemistry

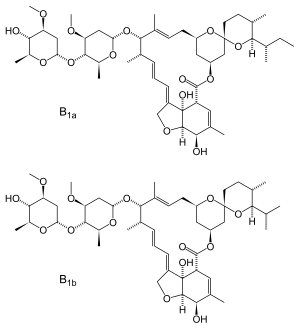

Fermentation of

Ivermectin is a macrocyclical lactone.[77]

History

The avermectin family of compounds was discovered by Satoshi Ōmura of Kitasato University and William Campbell of Merck.[6] In 1970, Ōmura isolated a strain of Streptomyces avermitilis from woodland soil near a golf course along the south east coast of Honshu, Japan.[6] Ōmura sent the bacteria to William Campbell, who showed that the bacterial culture could cure mice infected with the roundworm Heligmosomoides polygyrus.[6] Campbell isolated the active compounds from the bacterial culture, naming them "avermectins" and the bacterium Streptomyces avermitilis for the compounds' ability to clear mice of worms (in Latin: a 'without', vermis 'worms').[6] Of the various avermectins, Campbell's group found the compound "avermectin B1" to be the most potent when taken orally.[6] They synthesized modified forms of avermectin B1 to improve its pharmaceutical properties, eventually choosing a mixture of at least 80% 22,23-dihydroavermectin B1a and up to 20% 22,23-dihydroavermectin B1b, a combination they called "ivermectin".[6][78]

The discovery of ivermectin has been described as a combination of "chance and choice." Merck was looking for a broad-spectrum anthelmintic, which ivermectin is indeed; however, Campbell noted that they "...also found a broad-spectrum agent for the control of ectoparasitic insects and mites."[79]

Merck began marketing ivermectin as a veterinary antiparasitic in 1981.

Ivermectin earned the title of "wonder drug" for the treatment of nematodes and arthropod parasites.[82] Ivermectin has been used safely by hundreds of millions of people to treat river blindness and lymphatic filariasis.[6]

Half of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Campbell and Ōmura for discovering avermectin, "the derivatives of which have radically lowered the incidence of river blindness and lymphatic filariasis, as well as showing efficacy against an expanding number of other parasitic diseases".[14][83]

Society and culture

COVID-19 misinformation

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, laboratory research suggested ivermectin might have a role in preventing or treating COVID-19.[84] Online misinformation campaigns and advocacy boosted the drug's profile among the public. While scientists and physicians largely remained skeptical, some nations adopted ivermectin as part of their pandemic-control efforts. Some people, desperate to use ivermectin without a prescription, took veterinary preparations, which led to shortages of supplies of ivermectin for animal treatment. The FDA responded to this situation by saying "You are not a horse" in a Tweet to draw attention to the issue, which they were later sued for.[85][86]

Subsequent research failed to confirm the utility of ivermectin for COVID-19,[87][88] and in 2021 it emerged that many of the studies demonstrating benefit were faulty, misleading, or fraudulent.[89][90] Nevertheless, misinformation about ivermectin continued to be propagated on social media and the drug remained a cause célèbre for anti-vaccinationists and conspiracy theorists.[91]Economics

The initial price proposed by Merck in 1987 was

Ivermectin is considered an inexpensive drug.[94] As of 2019, ivermectin tablets (Stromectol) in the United States were the least expensive treatment option for lice in children at approximately US$9.30, while Sklice, an ivermectin lotion, cost around US$300 for 120 mL (4 US fl oz).[95]

As of 2019[update], the

Brand names

It is sold under the brand names Heartgard, Sklice

Research

Parasitic disease

Ivermectin has been researched in laboratory animals, as a potential treatment for trichinosis[31] and trypanosomiasis.[101]

Tropical diseases

As of 2016[update] ivermectin was studied as a potential antiviral agent against chikungunya and yellow fever.[102] In chikungunya, ivermectin showed a wide in vitro safety margin as an antiviral.[102]

Ivermectin is also of interest in the prevention of malaria, as it is toxic to both the malaria plasmodium itself and the mosquitos that carry it.[103][104] A direct effect on malaria parasites could not be shown in an experimental infection of volunteers with Plasmodium falciparum.[105] Use of ivermectin at higher doses necessary to control malaria is probably safe, though large clinical trials have not yet been done to definitively establish the efficacy or safety of ivermectin for prophylaxis or treatment of malaria.[106][58] Mass drug administration of a population with ivermectin to treat and prevent nematode infestation is effective for eliminating malaria-bearing mosquitos and thereby potentially reducing infection with residual malaria parasites.[107] Whilst effective in killing malaria-bearing mosquitos, a 2021 Cochrane review found that, to date, the evidence shows no significant impact on reducing incidence of malaria transmission from the community administration of ivermectin.[106]

One alternative to ivermectin is moxidectin, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in people with river blindness.[108] Moxidectin has a longer half-life than ivermectin and may eventually supplant ivermectin as it is a more potent microfilaricide, but there is a need for additional clinical trials, with long-term follow-up, to assess whether moxidectin is safe and effective for treatment of nematode infection in children and women of childbearing potential.[109][110]

There is tentative evidence that ivermectin kills

NAFLD

In 2013, ivermectin was demonstrated as a novel ligand of the

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ivermectin was researched for possible utility in preventing and treating COVID-19, but no good evidence of benefit was found.[118][119]

Veterinary use

Ivermectin is routinely used to control parasitic worms in the gastrointestinal tract of ruminant animals. These parasites normally enter the animal when it is grazing, pass the bowel, and set and mature in the intestines, after which they produce eggs that leave the animal via its droppings and can infest new pastures. Ivermectin is only effective in killing some of these parasites, this is because of an increase in anthelmintic resistance.[120] This resistance has arisen from the persistent use of the same anthelmintic drugs for the past 40 years.[121][122] Additionally, the use of Ivermectin for livestock has a profound impact on dung beetles, such as T. lusitanicus, as it can lead to acute toxicity within these insects.[123]

In dogs, ivermectin is routinely used as prophylaxis against

Ivermectin is sometimes used as an acaricide in reptiles, both by injection and as a diluted spray. While this works well in some cases, care must be taken, as several species of reptiles are very sensitive to ivermectin. Use in turtles is particularly contraindicated.[130]

A characteristic of the antinematodal action of ivermectin is its potency: for instance, to combat Dirofilaria immitis in dogs, ivermectin is effective at 0.001 milligram per kilogram of body weight when administered orally.[78]

For dogs, the insecticide spinosad may have the effect of increasing the toxicity of ivermectin.[131][132]

Notes

- Cochrane review concluded that the three drugs are equally safe and effective for treating ascariasis.[39]

- ^ New Drug Application Identifier: 50-742/S-022

References

- ^ "Search Page – Drug and Health Product Register". October 23, 2014. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Health Canada New Drug Authorizations: 2015 Highlights". Health Canada. May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Stromectol – ivermectin tablet". DailyMed. December 15, 2019. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Soolantra – ivermectin cream". DailyMed. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "List of nationally authorised medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. November 26, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2020.

- ^ PMID 28285851.

- PMID 22039784.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-24486-2. Archivedfrom the original on January 31, 2016.

- ^ PMID 26552892.

- ^ a b c d e "Ivermectin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Archivedfrom the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "Ascariasis – Resources for Health Professionals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). August 23, 2019. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- PMID 33278625.

- ^ "Ivermectin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ "Ivermectin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ "Ivermectin lotion: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Evershed N, McGowan M, Ball A. "Anatomy of a conspiracy theory: how misinformation travels on Facebook". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Fact-checking claim about the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19". PolitiFact. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- PMID 35726131.

- ^ a b "EMA advises against use of ivermectin for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 outside randomised clinical trials". European Medicines Agency. March 22, 2021. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- PMID 33888547.

- ^ "Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ "Rapid Increase in Ivermectin Prescriptions and Reports of Severe Illness Associated with Use of Products Containing Ivermectin to Prevent or Treat COVID-19" (PDF). CDC Health Alert Network. CDCHAN-00449. August 26, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "EMA advises against use of ivermectin for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 outside randomised clinical trials". European Medicines Agency. March 22, 2021. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "WHO advises that ivermectin only be used to treat COVID-19 within clinical trials". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- S2CID 24474879.

Ivermectin was a revelation. It had a broad spectrum of activity, was highly efficacious, acting robustly at low doses against a wide variety of nematode, insect and acarine parasites. It proved to be extremely effective against most common intestinal worms (except tapeworms), could be administered orally, topically or parentally and showed no signs of cross-resistance with other commonly used anti-parasitic compounds.

- ^ S2CID 149445017.

- ^ "Onchocerciasis". World Health Organization. June 14, 2019. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Strongyloidiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "26. Other Nematodes of Medical Importance". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 294. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "27. Aberrant Nematode Infections". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 299. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "Ascariasis – Resources for Health Professionals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). May 20, 2020. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ "Water related diseases – Ascariasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "18. Ascaris lumbricoides". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 211. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- PMID 32289194.

- ^ Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "17. Trichuris trichiura". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 201. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- S2CID 242599732.

- ^ a b "Scabies – Medications". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). October 2, 2019. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-19-284840-6.

- PMID 31083883.

- ^ "Pubic "Crab" Lice – Treatment". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). September 12, 2019. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- PMID 29091565.

- PMID 25441466.

- ^ "Ivermectin (PIM 292)". inchem.org. InChem. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ "Stromectol (ivermectin) dose, indications, adverse effects, interactions". www.pdr.net. Prescribers' Digital Reference. Archived from the original on April 25, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- S2CID 3441595.

- ^ "Ivermectin – Drug Monographs – Pediatric Care Online". American Academy of Pediatrics Drug Monographs. August 2021. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- PMID 31700976.

- PMID 31839144.

- ^ "Ivermectin (topical)". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. July 27, 2020. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "Ivermectin Levels and Effects while Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ PMID 31960060.

- PMID 33189582.

- ^ PMID 30968052.

- PMID 33189582.

Although relatively free from toxicity, ivermectin – when large overdoses are administered – may cross the blood–brain barrier, producing depressant effects on the CNS

- PMID 33878105.

Few hours after administration: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, salivation, tachycardia, hypotension, ataxia, pyramidal signs, binocular diplopia

- ^ Office of the Commissioner (March 12, 2021). "Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

You can also overdose on ivermectin, which can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension (low blood pressure), allergic reactions (itching and hives), dizziness, ataxia (problems with balance), seizures, coma and even death.

- PMID 32824399.

Based on the reported neurotoxicity and metabolic pathway of IVM, caution should be taken to conduct clinical trial on its antiviral potentials. The GABA-gated chloride channels in the human nervous system might be a target for IVM, this is because the BBB in disease-patient might be a weakened as a result of inflammation and other destructive processes, allowing IVM to cross the BBB and gain access to the CNS where it can elicit its neurotoxic effect

- OCLC 1037399847.

- from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ PMID 29511601.

- PMID 32378737.

- ^ "Rapid Increase in Ivermectin Prescriptions and Reports of Severe Illness Associated with Use of Products Containing Ivermectin to Prevent or Treat COVID-19". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 26, 2021. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ S2CID 226972704.

- ^ PMID 25130507.

- PMID 18446504.

- PMID 8763339.

- (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- PMID 2006872.

- ISBN 978-3-642-08314-3.

- PMID 15275618.

- ^ PMID 6308762.

- PMID 16179743.

- S2CID 22722403.

- PMID 22633470.

- PMID 16126457.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015". NobelPrize.org. March 18, 2023. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- PMID 32251768.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ Langford C (September 1, 2023). "Fifth Circuit sides with ivermectin-prescribing doctors in their quarrel with the FDA". Courthouse News Service.

- PMID 35726131.

- PMID 35353979.

- S2CID 237607620.

- ^ "Ivermectin: How false science created a Covid 'miracle' drug". BBC News. October 6, 2021. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Melissa Davey (July 15, 2021). "Huge study supporting ivermectin as Covid treatment withdrawn over ethical concerns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ PMID 21321478.

- ISBN 978-0191008412. Archivedfrom the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- PMID 33785846.

- ISBN 978-0323568883. Archivedfrom the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "Sklice – ivermectin lotion". DailyMed. November 9, 2017. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Adhikari S (May 27, 2014). "Alive Pharmaceutical (P) LTD.: Iver-DT". Alive Pharmaceutical (P) LTD. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- PMID 3832491.

- PMID 23135008.

- ^ PMID 26752081.

- PMID 28434401.

- PMID 31439040.

- PMID 32731386.

- ^ PMID 34184757.

- PMID 29629252.

- PMID 32715787.

- S2CID 46921091.

- PMID 29361336.

- PMID 28196978.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0323319690. Archivedfrom the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

Ivermectin treatment is emerging as a potential ancillary measure.

- ISBN 978-0702069130. Archivedfrom the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- PMID 23728580.

- PMID 28029021.

- PMID 35726131.

- PMID 35353979.

- PMID 22154968.

- PMID 26448902.

- PMID 27835769.

- PMID 32493927.

- ISBN 978-0-323-24485-5.

- PMID 17217086.

- ^ "MDR1 FAQs". Australian Shepherd Health & Genetics Institute, Inc. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007.

- ^ "Multidrug Sensitivity in Dogs". Washington State University's College of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015.

- PMID 17423775.

- ^ "Acarexx". Boehringer Ingelheim. April 11, 2016. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ISBN 978-1882770908.

- ^ "Comfortis- spinosad tablet, chewable". DailyMed. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ "Comfortis and ivermectin interaction Safety Warning Notification". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on August 29, 2009.

External links

- "Ivermectin Topical". MedlinePlus.