Synephrine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

4-[1-Hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]phenol | |

| Other names

p-Synephrine; Oxedrine; 4,β-Dihydroxy-N-methylphenethylamine

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.002.092 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H13NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 167.21 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless solid |

| Melting point | 162 to 164 °C (324 to 327 °F; 435 to 437 K) (R-(−)-enantiomer); 184 to 185 °C (racemate) |

| soluble | |

| Pharmacology | |

| C01CA08 (WHO) S01GA06 (WHO), QS01FB90 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Synephrine, or, more specifically, p-synephrine, is an

There is a difference between studies concerning synephrine as a single chemical entity (synephrine can exist in the form of either of two

In physical appearance, synephrine is a colorless, crystalline solid and is water-soluble. Its molecular structure is based on a

Natural occurrences

Synephrine, although already known as a synthetic

all plants of the family Rutaceae.Trace levels (0.003%) of synephrine have also been detected in the dried leaves of

However, this compound is found predominantly in a number of Citrus species, including "bitter" orange varieties.

In Citrus

Extracts of unripe fruit from Asian cultivars of

Sweet oranges of the Tarocco, Naveline and Navel varieties, bought on the Italian market, were found to contain ~13–34 μg/g (corresponding to 13–34 mg/kg) synephrine (with roughly equal concentrations in juice and separated pulp); from these results, it was calculated that eating one "average" Tarocco orange would result in the consumption of ~6 mg of synephrine.[12]

An analysis of 32 different orange "jams", originating mostly in the US and UK, but including samples from France, Italy, Spain, or Lebanon, showed synephrine levels ranging from 0.05 mg/g–0.0009 mg/g[b] in those jams made from bitter oranges, and levels of 0.05 mg/g–0.006 mg/g[c] of synephrine in jams made from sweet oranges.[13]

Synephrine has been found in

A sample of commercial Japanese C. unshiu juice was found to contain ~0.36 mg/g synephrine (or roughly 360 mg/L),[15] while in juice products obtained from a Satsuma mandarin variety grown in California, levels of synephrine ranged from 55 to 160 mg/L .[17]

Juices from "sweet" oranges purchased in Brazilian markets were found to contain ~10–22 mg/L synephrine; commercial orange soft drinks obtained on the Brazilian market had an average synephrine content of ~1 mg/L.[18] Commercial Italian orange juices contained ~13–32 mg/L of synephrine[12]

In a survey of over 50 citrus fruit juices, either commercially-prepared or hand-squeezed from fresh fruit, obtained on the US market, Avula and co-workers found synephrine levels ranging from ~4–60 mg/L;[d] no synephrine was detected in juices from grapefruit, lime, or lemon.[13]

An analysis of the synephrine levels in a range of different citrus fruits, carried out on juices that had been extracted from fresh, peeled fruit, was reported by Uckoo and co-workers, with the following results:

Marrs sweet orange (C. sinensis Tan.): ~85 mg/L; Nova tangerine (

Numerous additional comparable analyses of the synephrine content of Citrus fruits and products derived from them may be found in the research literature.

In humans and other animals

Low levels of synephrine have been found in normal human urine,[20][21] as well as in other mammalian tissue.[22][23] To reduce the likelihood that the synephrine detected in urine had a dietary origin, the subjects tested by Ibrahim and co-workers abstained from the consumption of any citrus products for 48 hours prior to providing urine samples.[20]

A 2006 study of synephrine in human

Stereoisomers

Since synephrine exists as either of two

Biosynthesis

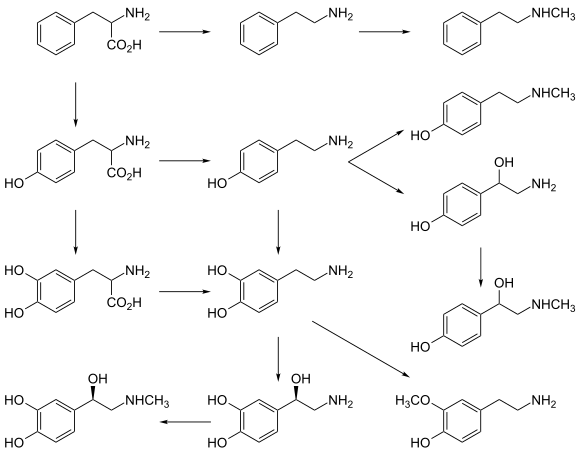

The biosynthesis of synephrine in Citrus species is believed to follow the pathway:

Presence in nutritional/dietary supplements

Some dietary supplements, sold for the purposes of promoting weight-loss or providing energy, contain synephrine as one of several constituents. Usually, the synephrine is present as a natural component of Citrus aurantium ("bitter orange"), bound up in the plant matrix, but could also be of synthetic origin, or a purified phytochemical (i.e. extracted from a plant source and purified to chemical homogeneity).[16][35][36] The concentration range found by Santana and co-workers in five different supplements purchased in the US was about 5–14 mg/g.[35]

Pharmaceutical use

As a synthetic drug, synephrine first appeared in Europe in the late 1920s, under the name of Sympatol. One of the earliest papers describing its pharmacological and toxicological properties was written by Lasch, who obtained it from the Viennese company Syngala.

There is no mention of synephrine in editions of Drill's Pharmacology in Medicine later than the 3rd, nor is there any reference to synephrine in the 2012 Physicians' Desk Reference, nor in the current FDA "Orange Book".

One current reference source describes synephrine as a vasoconstrictor that has been given to hypotensive patients, orally or by injection, in doses of 20–100 mg.[48]

One website from a healthcare media company, accessed in February, 2013, refers to oxedrine as being indicated for

Names

There has been some confusion about the biological effects of synephrine because of the similarity of this un-prefixed name to the names m-synephrine, Meta-synephrine and Neosynephrine, all of which refer to a related drug and naturally-occurring amine more commonly known as phenylephrine. Although there are chemical and pharmacological similarities between synephrine and phenylephrine, they are nevertheless different substances. The confusion is compounded by the fact that synephrine has been marketed as a drug under numerous different names, including Sympatol, Sympathol, Synthenate, and oxedrine, while phenylephrine has also been called m-Sympatol. The synephrine with which this article deals is sometimes referred to as p-synephrine in order to distinguish it from its positional isomers, m-synephrine and o-synephrine. A comprehensive listing of alternative names for synephrine may be found in the ChemSpider entry (see Chembox, at right). Confusion exists over the distinctions between p- and m-synephrine.[50] However, an examination of the references cited in support of this statement show that all the evidence for the presence of m-synephrine in C. aurantium derives from a report by Penzak and co-workers,[51] whose Abstract states that m-synephrine was found in C. aurantium, whereas a close reading of the text of the paper itself reveals that the authors (although apparently uncertain about which synephrine regio-isomer had been found in the plant by earlier investigators) were aware that their analytical technique could not distinguish between m- and p-synephrine, and did not claim that m-synephrine was present. Thus the Abstract is at variance with the experimental findings given in the full text of the paper, but this error has propagated through subsequent publications. Even the name "p-synephrine" is not unambiguous, since it does not specify stereochemistry. The only completely unambiguous names for synephrine are: (R)-(−)-4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]phenol (for the l-enantiomer); (S)-(+)-4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]phenol (for the d-enantiomer); and (R,S)-4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]phenol (for the racemate, or d,l-synephrine) (see Chemistry section).

Chemistry

Properties

In terms of molecular structure, synephrine has a

Common salts of

The presence of the hydroxy-group on the

Racemic synephrine has been resolved using ammonium 3-bromo-camphor-8-sulfonate.[11][55] The enantiomers were not characterized as their free bases, but converted to the hydrochloride salts, with the following properties:[55]

(S)-(+)-C9H13NO2.HCl: m.p. 178 °C; [α] = +42.0°, c 0.1 (H2O); (R)-(−)-C9H13NO2.HCl: m.p. 176 °C; [α] = −39.0°, c 0.2 (H2O)

(−)-Synephrine, as the free base isolated from a Citrus source, has m.p. 162–164 °C (with decomposition).[3][4][dead link]

The X-ray structure for synephrine has been determined.[55]

Synthesis

Early and seemingly inefficient syntheses of synephrine were discussed by Priestley and Moness, writing in 1940.[56] These chemists optimized a route beginning with the O-benzoylation of p-hydroxy-phenacyl chloride, followed by reaction of the resulting O-protected chloride with N-methyl-benzylamine to give an amino-ketone. This intermediate was then hydrolyzed with HCl/alcohol to the p-hydroxy-aminoketone, and the product then reduced catalytically to give (racemic) synephrine.

A later synthesis, due to Bergmann and Sulzbacher, began with the O-benzylation of p-hydroxy-benzaldehyde, followed by a Reformatskii reaction of the protected aldehyde with ethyl bromoacetate/Zn to give the expected β-hydroxy ester. This intermediate was converted to the corresponding acylhydrazide with hydrazine, then the acylhydrazide reacted with HNO2, ultimately yielding the p-benzyloxy-phenyloxazolidone. This was N-methylated using dimethyl sulfate, then hydrolyzed and O-debenzylated by heating with HCl, to give racemic synephrine.[57]

Structural relationships

Much reference has been made in the literature (both lay and professional) of the structural kinship of synephrine with ephedrine, or with phenylephrine, often with the implication that the perceived similarities in structure should result in similarities in pharmacological properties. However, from a chemical perspective, synephrine is also related to a very large number of other drugs whose structures are based on the phenethylamine skeleton, and although some properties are common, others are not, making unqualified comparisons and generalizations inappropriate.

Thus, replacement of the N-

If the synephrine phenolic 4-OH group is shifted to the meta-, or 3-position on the benzene ring, the compound known as phenylephrine (or m-synephrine, or "Neo-synephrine") results; if the same group is shifted to the ortho-, or 2-position on the ring, o-synephrine results.

Addition of another phenolic –OH group to the 3-position of the benzene ring produces the

Extension of the synephrine N-methyl substituent by one

The above structural relationships all involve a change at one position in the synephrine molecule, and numerous other similar changes, many of which have been explored, are possible. However, the structure of ephedrine differs from that of synephrine at two different positions: ephedrine has no substituent on the phenyl ring where synephrine has a 4-OH group, and ephedrine has a methyl group on the position α- to the N in the side-chain, where syneprine has only a H atom. Furthermore, "synephrine" exists as either of two enantiomers, while "ephedrine" exists as one of four different enantiomers; there are, in addition, racemic mixtures of these enantiomers.

The main differences of the synephrine isomers compared for example to the ephedrines are the hydroxy-substitutions on the benzene ring. Synephrines are direct sympathomimetic drugs while the ephedrines are both direct and indirect sympathomimetics. One of the main reasons for these differential effects is the obviously increased polarity of the hydroxy-substituted phenyl ethyl amines which renders them less able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier as illustrated in the examples for tyramine and the amphetamine analogs.[60]

Pharmacology

Synopsis

Classical pharmacological studies on animals and isolated animal tissues showed that the principal actions of parenterally-administered synephrine included raising blood-pressure, dilating the pupil, and constricting peripheral blood vessels.

There is now ample evidence(what evidence?) that synephrine produces most of its biological effects by acting as an

In common with virtually all other simple phenylethanolamines (β-hydroxy-phenethylamines), the (R)-(−)-, or l-, enantiomer of synephrine is more potent than the (S)-(+)-, or d-, enantiomer in most, but not all preparations studied. However, the majority of studies have been conducted with a racemic mixture of the two enantiomers.

Since the details regarding such variables as test species, receptor source, route of administration, drug concentration, and stereochemical composition are important but often incomplete in other Reviews and Abstracts of research publications, many are provided in the more technical review below, in order to support as fully as possible the broad statements made in this Synopsis.

Pharmacology research

Pharmacological studies on synephrine date back to the late 1920s, when it was observed that injected synephrine raised blood pressure, constricted peripheral blood vessels, dilated pupils, stimulated the uterus, and relaxed the intestines in experimental animals.[37][61][62] Representative of this early work is the paper by Tainter and Seidenfeld, who were the first researchers to systematically compare the different effects of the two synephrine enantiomers, d- and l- synephrine, as well as of the racemate, d,l-synephrine, in various animal assays.[41] In experiments on anesthetized cats, Tainter and Seidenfeld confirmed earlier reports of the increase in blood pressure produced by intravenous doses of synephrine, showing that the median

Using cats and dogs, Tainter and Seidenfeld observed that neither d- nor l-synephrine caused any changes in the tone of normal

In experiments with isolated sheep

Qualitatively similar results were obtained in a rabbit ear preparation: 25 mg l-synephrine produced significant (50%) vasoconstriction, while the same concentration of d-synephrine elicited essentially no response. In contrast, d,l-synephrine did not produce any constriction up to 25 mg, but 25 – 50 mg caused a relaxation of the blood vessels, which again suggested that the d-isomer might be inhibiting the action of the l-isomer.[41]

Experiments on strips of rabbit duodenum showed that l-synephrine caused a modest reduction in contractions at a concentration of 1:17000,[g] but that the effects of the d- and d,l- forms were much weaker.[41]

Racemic synephrine, given intramuscularly, or by instillation, was found to significantly reduce the inflammation caused by instillation of mustard oil into the eyes of rabbits.[41]

Subcutaneous injection of racemic synephrine into rabbits was reported to cause a large rise in

In experiments on anesthetized cats, Papp and Szekeres found that synephrine (stereochemistry unspecified) raised the thresholds for auricular and ventricular

Evidence that synephrine might have some central effects comes from the research of Song and co-workers, who studied the effects of synephrine in mouse models[h] of anti-depressant activity.[65] These researchers observed that oral doses of 0.3 – 10 mg/kg of racemic synephrine were effective in shortening the duration of immobility[i] produced in the assays, but did not cause any changes in spontaneous motor activity in separate tests. This characteristic immobility could be counteracted by the pre-administration of prazosin.[j] Subsequent experiments using the individual enanatiomers of synephrine revealed that although the d-isomer significantly reduced the duration of immobility in the tail suspension test, at an oral dose of 3 mg/kg, the l-isomer had no effect at the same dose. In mice pre-treated with reserpine,[k] an oral dose of 0.3 mg/kg d-synephrine significantly reversed the hypothermia, while l-synephrine required a dose of 1 mg/kg to be effective. Experiments with slices of cerebral cortex taken from rat brain showed that d-synephrine inhibited the uptake of [3H]-norepinephrine with an IC50 = 5.8 μM; l-synephrine was less potent (IC50 = 13.5 μM). d-Synephrine also competitively inhibited the binding of nisoxetine[l] to rat brain cortical slices, with a Ki = 4.5 μM; l-synephrine was less potent (Ki = 8.2 μM). In experiments on the release of [3H]-norepinephrine from rat brain cortical slices, however, the l-isomer of synephrine was a more potent enhancer of the release (EC50 = 8.2 μM) than the d-isomer (EC50 = 12.3 μM). This enhanced release by l-synephrine was blocked by nisoxetine.[66]

Burgen and Iversen, examining the effect of a broad range of phenethylamine-based drugs on [14C]-norepinephrine-uptake in the isolated rat heart, observed that racemic synephrine[m] was a relatively weak inhibitor (IC50 = 0.12 μM) of the uptake.[67]

Another receptor-oriented study by Wikberg revealed that synephrine (stereochemistry unspecified) was a more potent agonist at guinea pig aorta α1 receptors (pD2 = 4.81) than at ileum α2 receptors (pD2 = 4.48), with a relative affinity ratio of α2/α1 = 0.10. Although clearly indicating a selectivity of synephrine for α1 receptors, its potency at this receptor sub-class is still relatively low, in comparison with that of phenylephrine (pD2 at α1 = 6.32).[68]

Brown and co-workers examined the effects of the individual enantiomers of synephrine on α1 receptors in rat aorta, and on α2 receptors in rabbit saphenous vein. In the aorta preparation, l-synephrine gave a pD2 = 5.38 (potency relative to norepinephrine = 1/1000), while d-synephrine had a pD2 = 3.50 (potency relative to norepinephrine = 1/50000); in comparison, l-phenylephrine had pD2 = 7.50 (potency relative to norepinephrine ≃ 1/6). No antagonism of norepinephrine was produced by concentrations of l-synephrine up to 10−6 M. In the rabbit saphenous assay, the pD2 of l-synephrine was 4.36 (potency relative to norepinephrine ≃ 1/1700), and that of d-synephrine was < 3.00; in comparison, l-phenylephrine had pD2 = 5.45 (potency relative to norepinephrine ≃ 1/140). No antagonism of norepinephrine was produced by concentrations of l-synephrine up to 10−5 M.[69]

A study of the effects of synephrine (stereochemistry unspecified) on strips of guinea pig aorta and on the field-stimulated guinea pig ileum showed that synephrine had an agonist potency of −logKa = 3.75 in the aorta assay. In comparison, epinephrine had a potency of −logKa = 5.70. There was no significant effect on the ileum at synephrine concentrations up to about 2 × 10−4 M, indicating selectivity for the α1 receptor, but relatively low potency.[70]

In binding experiments with central adrenergic receptors, using a preparation from rat cerebral cortex, l-synephrine had pIC50 = 3.35, and d-synephrine had pIC50 = 2.42 in competition against [3H]-prazosin (standard α1 ligand); against [3H]-yohimbine (standard α2 ligand), l-synephrine showed a pIC50 = 5.01, and d-synephrine showed a pIC50 = 4.17.[69]

Experiments conducted by Hibino and co-workers also showed that synephrine (stereochemistry unspecified) produced a dose-dependent constriction of isolated rat aorta strips, in the concentration range 10−5–3 × 10−6 M. This constriction was found to be competitively antagonized by prazosin (a standard α1 antagonist) and

In studies on guinea pig

Experiments with cultured

The binding of racemic synephrine to cloned human adrenergic receptors has been examined: Ma and co-workers found that synephrine bound to α1A, α2A and α2C with low affinity (pKi = 4.11 for α1A; 4.44 for α2A; 4.61 for α2C). Synephrine behaved as a partial agonist at α1A receptors, but as an antagonist at α2A and α2C sub-types.[74]

Racemic synephrine has been shown to be an

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of synephrine were studied by Hengstmann and Aulepp, who reported a peak plasma concentration at 1–2 hours, with an elimination half-life (T1/2) of ~ 2 hours.[77]

Metabolism

Studies of the metabolism of synephrine by

Effects in humans

This section needs more primary sources. (January 2014) |  |

A number of studies of the effects of synephrine in humans, most of them focusing on its cardiovascular properties, have been performed since its introduction as a synthetic drug around 1930.

The i.m. administration of 75–500 mg of synephrine did not relieve acute

Administration of synephrine by continuous intravenous infusion, at the rate of 4 mg/minute, significantly increased mean arterial and

There are a number of studies, references to many of which may be found in the review by Stohs and co-workers[86] dealing with the effects produced by dietary supplements and herbal medications that contain synephrine as only one of many different chemical ingredients. These are outside the scope of the present article (see also the "Safety/Efficacy/Controversy" sub-section).

Toxicology

The acute toxicities of racemic synephrine in different animals, reported in terms of "maximum tolerated dose" after s.c administration, were as follows: mouse: 300 mg/kg; rat: 400 mg/kg; guinea pig: 400 mg/kg. "Lethal doses", given s.c., were found to be: mouse: 400 mg/kg; rat: 500 mg/kg; guinea pig: 500 mg/kg.[37] Another study of this compound,[q] administered i.v. in mice, gave an LD50 = 270 mg/kg.[63]

The "subchronic toxicity" of synephrine was judged to be low in mice, after administration of oral doses of 30 and 300 mg/kg over a period of 28 days. Generally, this treatment did not result in significant alterations in biochemical or hematological parameters, nor in relative organ weights, but some changes were noted in glutathione (GSH) concentration, and in the activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPx).[87]

Safety/efficacy/controversy

There exists considerable controversy about the safety and/or efficacy of synephrine-containing preparations, which are often confused with synephrine alone, sometimes with m-synephrine.[16][50][86][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96] Furthermore, this body of literature deals with mixtures containing synephrine as only one of several biologically active components, even, in some cases, without explicit confirmation of the presence of synephrine.

Invertebrates

In insects, synephrine has been found to be a very potent agonist at many invertebrate

Footnotes

- ^ Synephrine does however not appear in the current FDA "Orange Book" or the 2012 Physicians' Desk Reference.

- ^ About 1.0–0.02 mg/serving, based on a serving size of ~20g.

- ^ About 1.0–0.1 mg/serving.

- ^ Corresponding to roughly 1–15 mg/serving, assuming a 1-cup or 250 mL serving size.

- ^ ~ 5 x 10−4M.

- ^ ~ 2 x 10−3M.

- ^ ~ 3 × 10−4M.

- ^ Tail suspension and enforced swimming.

- ^ Ostensibly correlated to anti-depressant activity.

- ^ An adrenergic antagonist selective for α1 receptors.

- ^ Reversal of reserpine-induced hypothermia by a drug is a classical test for potential anti-depressant properties.

- ^ A selective inhibitor of the norepinephrine transporter.

- ^ Referred to here as "oxedrine".

- ^ A drug often used as a selective 5-HT2A antagonist.

- ^ Used here as a selective 5-HT1D antagonist.

- ^ Used as a non-selective β-antagonist

- ^ Referred to as "Sympathol".

See also

References

- ^ SA, HCI Solutions. "Neo-Synephrine HCl - compendium.ch". compendium.ch. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- S2CID 25766699.

- ^ doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)51679-3.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b [1] [dead link]

- PMID 5495514.

- PMID 16824714.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- PMID 23186318.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 0-9630096-9-9.

- doi:10.1248/cpb.40.3284.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 15862657.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 16366666.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 17580614.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b "Cross-reference for Citrus species and common names". Plantnames.unimelb.edu.au. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ PMID 8833327.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c "American Botanical Council : Bitter Orange Peel and Synephrine" (PDF). Abc.herbalgram.org. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- PMID 18771270.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.10.050.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21147342.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 6435479.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17089346.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 2100639.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 7376144.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 43823090.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 1673803.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 12110397.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20399443.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - doi:10.1248/cpb.43.1158.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- ^ .

- PMID 20403465.

- PMID 19948186.

- PMID 15860375.

- PMID 24374199.

- ^ doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.076.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16164886.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 24160900.

- S2CID 28747772.

- ^ H. Legerlotz, US Patent 1,932,347 (October 24, 1933).

- ^ doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)09117-7.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ .

- .

- ^ .

- .

- ^ J. R. DiPalma (Ed.) (1965),Drill's Pharmacology in Medicine,3rd Ed., p.494, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- ^ a b C. O. Wilson, O. Gisvold, and R. F. Doerge (Eds.) (1966). Textbook of Organic Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry, 5th ed., p.438, Lippincott, Philadelphia.

- ^ D. M. Aviado (Ed.), 1972. Krantz & Carr's Pharmacologic Principles of Medical Practice, 8th Ed., p.526, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore.

- ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ https://www.mims.com/USA/drug/info/oxedrine/?type=full&mtype=generic [permanent dead link]

- ^ PMID 21075161.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 32631329.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 14323148.

- .

- ^ The Merck Index, 10th Ed. (1983), p. 1295, Merck & Co., Rahway, NJ.

- ^ a b c d J. M. Midgley, C. M. Thonoor, A. F. Drake, C. M. Williams, A. E. Koziol and G. J. Palenik (1989). "The resolution and absolute configuration by X-ray crystallography of the isomeric octopamines and synephrines." J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 963-969.

- .

- .

- PMID 20295509.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 30482120.

- PMID 412682.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 21414110.

- ^ G. Kuschinsky (1930)). "Untersuchungen über Sympatol, einen adrenalinähnlichen Körper." Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 156 290 - 308.

- ^ PMID 13000630.

- PMID 4968334.

- S2CID 28440606.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 12625027.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19108208.

- S2CID 4278917.

- ^ PMID 2833972.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 6131121.

- PMID 19721332.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 38557968.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 34370879.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 41387315.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15860375.

- S2CID 10829497.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Hengstmann J. H., Aulepp H. (1978). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of 3H-synephphrine". Arzneimittelforschung. 28: 2326–2331.

- S2CID 6129913.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ U. von Euler and G. Liljestrand (1929). Skand. Arch. Physiol. 55 1.

- S2CID 34593711.

- S2CID 25139273.

- PMID 18731684.

- ^ PMID 4096743.

- .

- S2CID 35942851.

- ^ S2CID 32789083.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19275924.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15301335.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15595351.

- PMID 15541270.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15819293.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15830849.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 13842012.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20069086.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20548833.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- PMID 6275071.

- PMID 4386272.

- PMID 347053.

- .

- .

- .