Tyramine

N-methyltyramine, octopamine | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.103 g/cm3 predicted[2] |

| Melting point | 164.5 °C (328.1 °F) [3] |

| Boiling point | 206 °C (403 °F) at 25 mmHg; 166 °C at 2 mmHg[3] |

| |

| |

Tyramine (/ˈtaɪrəmiːn/ TY-rə-meen) (also spelled tyramin), also known under several other names,[note 1] is a naturally occurring trace amine derived from the amino acid tyrosine.[4] Tyramine acts as a catecholamine releasing agent. Notably, it is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier, resulting in only non-psychoactive peripheral sympathomimetic effects following ingestion. A hypertensive crisis can result, however, from ingestion of tyramine-rich foods in conjunction with the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

Occurrence

Tyramine occurs widely in

Specific foods containing considerable amounts of tyramine include:[6][7]

- strong or aged cheeses: cheddar, Swiss, Parmesan, Stilton, Gorgonzola or blue cheeses, Camembert, feta, Muenster

- meats that are cured, smoked, or processed, such as salami, pepperoni, dry sausages, hot dogs, bologna, bacon, corned beef, pickled or smoked fish, caviar, aged chicken livers, soups or gravies made from meat extract

- pickled or fermented foods: sauerkraut, kimchi, tofu (especially stinky tofu), pickles, miso soup, bean curd, tempeh, sourdough breads

- condiments: soy, shrimp, fish, miso, teriyaki, and bouillon-based sauces

- drinks: beer (especially tap or home-brewed), vermouth, red wine, sherry, liqueurs

- beans, vegetables, and fruits: fermented or pickled vegetables, overripe fruits

- chocolate[8]

Scientists more and more consider tyramine in food as an aspect of safety.[9] They propose projects of regulations aimed to enact control of biogenic amines in food by various strategies, including usage of proper fermentation starters, or preventing their decarboxylase activity.[10] Some authors wrote that this has already given positive results, and tyramine content in food is now lower than it has been in the past.[11]

In plants

Mistletoe (toxic and not used by humans as a food, but historically used as a medicine).[12]

In animals

Tyramine also plays a role in animals including: In

Physical effects and pharmacology

Evidence for the presence of tyramine in the human brain has been confirmed by postmortem analysis.

Tyramine is physiologically metabolized by

Additionally, cocaine has been found to block blood pressure rise that is originally attributed to tyramine, which is explained by the blocking of adrenaline by cocaine from reabsorption to the brain.[27]

The first signs of this effect were discovered by a British pharmacist who noticed that his wife, who at the time was on MAOI medication, had severe headaches when eating cheese.[28] For this reason, it is still called the "cheese reaction" or "cheese crisis", although other foods can cause the same problem.[29]

Most processed cheeses do not contain enough tyramine to cause hypertensive effects, although some aged cheeses (such as Stilton) do.[30][31]

A large dietary intake of tyramine (or a dietary intake of tyramine while taking MAO inhibitors) can cause the tyramine pressor response, which is defined as an increase in

Research reveals a possible link between

If one has had repeated exposure to tyramine, however, there is a decreased pressor response; tyramine is degraded to octopamine, which is subsequently packaged in synaptic vesicles with norepinephrine (noradrenaline).[

When using a MAO inhibitor (MAOI), an intake of approximately 10 to 25 mg of tyramine is required for a severe reaction, compared to 6 to 10 mg for a mild reaction.[36]

Biosynthesis

Biochemically, tyramine is produced by the decarboxylation of tyrosine via the action of the enzyme tyrosine decarboxylase.[37] Tyramine can, in turn, be converted to methylated alkaloid derivatives N-methyltyramine, N,N-dimethyltyramine (hordenine), and N,N,N-trimethyltyramine (candicine).

-

Tyramine

-

N-Methyltyramine

-

N,N-Dimethyltyramine (hordenine)

-

N,N,N-Trimethyltyramine (candicine)

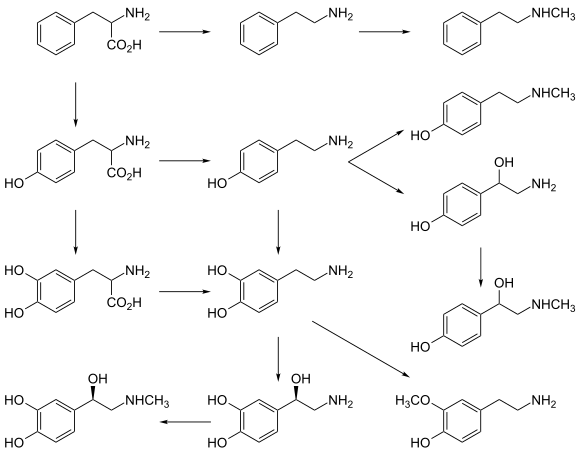

In humans, tyramine is produced from tyrosine, as shown in the following diagram.

Chemistry

In the laboratory, tyramine can be synthesized in various ways, in particular by the decarboxylation of tyrosine.[38][39][40]

Legal status

United States

Tyramine is a Schedule I

This ban is likely the product of lawmakers overly eager to ban

Notes

References

- .

- ^ SciFinder, Calculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software V11.02 (© 1994-2021 ACD/Labs)

- ^ a b The Merck Index, 10th Ed. (1983), p. 1405, Rahway: Merck & Co.

- ^ "tyramine | C8H11NO". PubChem. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ T. A. Smith (1977) Phytochemistry 16 9–18.

- ^ Hall-Flavin DK (18 December 2018). "Avoid the combination of high-tyramine foods and MAOIs". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Robinson J (21 June 2020). "Tyramine-Rich Foods As A Migraine Trigger & Low Tyramine Diet". WebMD.

- ^ "Tyramine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- PMID 33418895.

- .

- PMID 21971008.

- ^ "Tyramine". American Chemical Society. 19 December 2005.

- S2CID 14914393.

- S2CID 2056338.

- S2CID 80723865.

- PMID 623853.

- PMID 16831861.

- S2CID 2864195.

- S2CID 178180.

- PMID 27424325.

- ^ "Trimethylamine monooxygenase (Homo sapiens)". BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. July 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ PMID 19948186.

- ^ PMID 15860375.

- ^ PMID 24374199.

- ^ "4-Hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde". Human Metabolome Database – Version 4.0. University of Alberta. 23 July 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ProQuest 1346292101.

- PMID 19742203.

- Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 30–31. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- S2CID 6118722.

- ^ "Tyramine-restricted Diet" (PDF). W.B. Saunders Company. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Tyramine". Biochemistry. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- PMID 324566.

- S2CID 1548732.

- ^ "Headache Sufferer's Diet | National Headache Foundation". National Headache Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- S2CID 902921.

- ^ "Tyrosine metabolism - Reference pathway". Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ a b "Statutes & Constitution :View Statutes : Online Sunshine". leg.state.fl.us. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- PMID 26042107.