Bacterial taxonomy

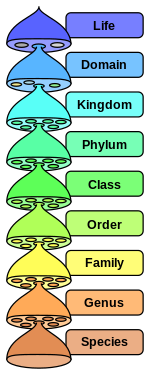

Bacterial taxonomy is subfield of taxonomy devoted to the classification of bacteria specimens into taxonomic ranks.

In the

Bacterial taxonomy is the classification of strains within the domain Bacteria into hierarchies of similarity. This classification is similar to that of

Diversity

Bacteria (prokaryotes, together with Archaea) share many common features. These commonalities include the lack of a nuclear membrane, unicellularity, division by binary-fission and generally small size. The various species can be differentiated through the comparison of several characteristics, allowing their identification and classification. Examples include:

- Phylogeny: All bacteria stem from a common ancestor and diversified since, and consequently possess different levels of evolutionary relatedness (see Timeline of evolution)

- Metabolism: Different bacteria may have different metabolic abilities (see Microbial metabolism)

- Environment: Different bacteria thrive in different environments, such as high/low temperature and salt (see Extremophiles)

- Morphology: There are many structural differences between bacteria, such as cell shape, Gram stain (number of lipid bilayers) or bilayer composition (see Bacterial cellular morphologies, Bacterial cell structure)

History

First descriptions

Bacteria were first observed by

Early described genera of bacteria include

The term Bacterium, introduced as a genus by Ehrenberg in 1838,[9] became a catch-all for rod-shaped cells.[7]

Early formal classifications

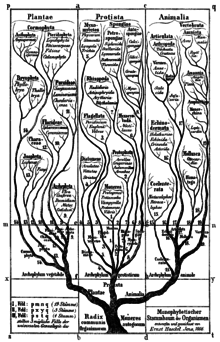

Bacteria were first classified as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes, which along with the Schizophyceae (blue green algae/Cyanobacteria) formed the phylum Schizophyta.[11]

- die Gymnomoneren (no envelope)

- Protogenes – such as Protogenes primordialis, now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium

- Protamaeba – now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium

- Vibrio – a genus of comma shaped bacteria first described in 1854[12])

- Bacterium – a genus of rod shaped bacteria first described in 1828, that later gave its name to the members of the Monera, formerly referred to as "a moneron" (plural "monera") in English and "eine Moneren"(fem. pl. "Moneres") in German

- Bacillus – a genus of spore-forming rod shaped bacteria first described in 1835[13]

- Spirochaeta – thin spiral shaped bacteria first described in 1835[13]

- Spirillum – spiral shaped bacteria first described in 1832[14]

- etc.

- die Lepomoneren (with envelope)

- Protomonas – now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium. The name was reused in 1984 for an unrelated genus of Bacteria[15]

- Vampyrella – now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium

The classification of Ferdinand Cohn (1872) was influential in the nineteenth century, and recognized six genera: Micrococcus, Bacterium, Bacillus, Vibrio, Spirillum, and Spirochaeta.[7]

The group was later reclassified as the

The classification of Cyanobacteria (colloquially "blue green algae") has been fought between being algae or bacteria (for example, Haeckel classified Nostoc in the phylum Archephyta of Algae[10]).

in 1905, Erwin F. Smith accepted 33 valid different names of bacterial genera and over 150 invalid names,[17] and Vuillemin, in a 1913 study,[18] concluded that all species of the Bacteria should fall into the genera Planococcus, Streptococcus, Klebsiella, Merista, Planomerista, Neisseria, Sarcina, Planosarcina, Metabacterium, Clostridium, Serratia, Bacterium, and Spirillum.

Cohn[19] recognized four tribes: Spherobacteria, Microbacteria, Desmobacteria, and Spirobacteria. Stanier and van Neil[20] recognized the kingdom Monera with two phyla, Myxophyta and Schizomycetae, the latter comprising classes Eubacteriae (three orders), Myxobacteriae (one order), and Spirochetae (one order). Bisset[21] distinguished 1 class and 4 orders: Eubacteriales, Actinomycetales, Streptomycetales, and Flexibacteriales. Walter Migula's system,[22] which was the most widely accepted system of its time and included all then-known species but was based only on morphology, contained the three basic groups Coccaceae, Bacillaceae, and Spirillaceae, but also Trichobacterinae for filamentous bacteria. Orla-Jensen[23] established two orders: Cephalotrichinae (seven families) and Peritrichinae (presumably with only one family). Bergey et al.[24] presented a classification which generally followed the 1920 Final Report of the Society of American Bacteriologists Committee (Winslow et al.), which divided class Schizomycetes into four orders: Myxobacteriales, Thiobacteriales, Chlamydobacteriales, and Eubacteriales, with a fifth group being four genera considered intermediate between bacteria and protozoans: Spirocheta, Cristospira, Saprospira, and Treponema.

However, different authors often reclassified the genera due to the lack of visible traits to go by, resulting in a poor state which was summarised in 1915 by Robert Earle Buchanan.[25] By then, the whole group received different ranks and names by different authors, namely:

- Schizomycetes (Naegeli 1857)[11]

- Bacteriaceae (Cohn 1872 a)[26]

- Bacteria (Cohn 1872 b)[27]

- Schizomycetaceae (DeToni and Trevisan 1889)[28]

Furthermore, the families into which the class was subdivided changed from author to author and for some, such as Zipf, the names were in German and not in Latin.[29]

The first edition of the Bacteriological Code in 1947 sorted out several problems.

A. R. Prévot's system[31][32]) had four subphyla and eight classes, as follows:

- Eubacteriales (classes Asporulales and Sporulales)

- Mycobacteriales (classes Actinomycetales, Myxobacteriales, and Azotobacteriales)

- Algobacteriales (classes Siderobacteriales and Thiobacteriales)

- Protozoobacteriales (class Spirochetales)

| Linnaeus 1735[33] |

Haeckel 1866[34] |

Chatton 1925[35] |

Copeland 1938[36] |

Whittaker 1969[37] |

Woese et al. 1990[38] |

Cavalier-Smith 1998,[39] 2015[40] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 kingdoms | 3 kingdoms | 2 empires | 4 kingdoms | 5 kingdoms | 3 domains | 2 empires, 6/7 kingdoms |

| (not treated) | Protista | Prokaryota

|

Monera | Monera | Bacteria | Bacteria |

| Archaea | Archaea (2015) | |||||

Eukaryota

|

Protoctista

|

Protista | Eucarya | "Protozoa" | ||

| "Chromista" | ||||||

Vegetabilia

|

Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | ||

| Fungi | Fungi | |||||

| Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia |

Informal groups based on Gram staining

Despite there being little agreement on the major subgroups of the Bacteria,

- Gracilicutes (gram-negative)

- Photobacteria (photosynthetic): class Oxyphotobacteriae (water as electron donor, includes the order Cyanobacteriales=blue-green algae, now phylum Cyanobacteria) and class Anoxyphotobacteriae (anaerobic phototrophs, orders: Rhodospirillales and Chlorobiales

- Scotobacteria (non-photosynthetic, now the Proteobacteria and other gram-negative nonphotosynthetic phyla)

- Firmacutes [sic] (gram-positive, subsequently corrected to Firmicutes[43])

- several orders such as Bacillales and Actinomycetales (now in the phylum Actinobacteria)

- Mollicutes (gram variable, e.g. Mycoplasma)

- Mendocutes (uneven gram stain, "methanogenic bacteria", now known as the Archaea)

Molecular era

"Archaic bacteria" and Woese's reclassification

Woese argued that the bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes represent separate lines of descent that diverged early on from an ancestral colony of organisms.

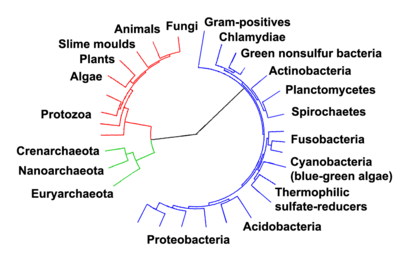

With improved methodologies it became clear that the methanogenic bacteria were profoundly different and were (erroneously) believed to be relics of ancient bacteria[51] thus Carl Woese, regarded as the forerunner of the molecular phylogeny revolution, identified three primary lines of descent: the Archaebacteria, the Eubacteria, and the Urkaryotes, the latter now represented by the nucleocytoplasmic component of the Eukaryotes.[52] These lineages were formalised into the rank Domain (regio in Latin) which divided Life into 3 domains: the Eukaryota, the Archaea and the Bacteria.[2]

Subdivisions

In 1987 Carl Woese divided the Eubacteria into 11 divisions based on 16S ribosomal RNA (SSU) sequences, which with several additions are still used today.[53][54]

Opposition

While the three domain system is widely accepted,[55] some authors have opposed it for various reasons.

One prominent scientist who opposes the three domain system is Thomas Cavalier-Smith, who proposed that the Archaea and the Eukaryotes (the Neomura) stem from Gram positive bacteria (Posibacteria), which in turn derive from gram negative bacteria (Negibacteria) based on several logical arguments,[56][57] which are highly controversial and generally disregarded by the molecular biology community (c.f. reviewers' comments on,[57] e.g. Eric Bapteste is "agnostic" regarding the conclusions) and are often not mentioned in reviews (e.g.[58]) due to the subjective nature of the assumptions made.[59]

However, despite there being a wealth of statistically supported studies towards the rooting of the tree of life between the Bacteria and the Neomura by means of a variety of methods,[60] including some that are impervious to accelerated evolution—which is claimed by Cavalier-Smith to be the source of the supposed fallacy in molecular methods[56]—there are a few studies which have drawn different conclusions, some of which place the root in the phylum Firmicutes with nested archaea.[61][62][63]

Radhey Gupta's molecular taxonomy, based on conserved signature sequences of proteins, includes a monophyletic Gram negative clade, a monophyletic Gram positive clade, and a polyphyletic Archeota derived from Gram positives.[64][65][66] Hori and Osawa's molecular analysis indicated a link between Metabacteria (=Archeota) and eukaryotes.[67] The only cladistic analyses for bacteria based on classical evidence largely corroborate Gupta's results (see comprehensive mega-taxonomy).

Authorities

Classification is the grouping of organisms into progressively more inclusive groups based on phylogeny and phenotype, while nomenclature is the application of formal rules for naming organisms.[72]

Nomenclature authority

Despite there being no official and complete classification of prokaryotes, the names (nomenclature) given to prokaryotes are regulated by the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (

Classification authorities

As taxa proliferated, computer aided taxonomic systems were developed. Early non networked identification software entering widespread use was produced by Edwards 1978, Kellogg 1979, Schindler, Duben, and Lysenko 1979, Beers and Lockhard 1962, Gyllenberg 1965, Holmes and Hill 1985, Lapage et al 1970 and Lapage et al 1973.[74]: 63

Today the taxa which have been correctly described are reviewed in Bergey's manual of Systematic Bacteriology, which aims to aid in the identification of species and is considered the highest authority.[42] An online version of the taxonomic outline of bacteria and archaea (TOBA) is available [1].

List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) is an online database which currently contains over two thousand accepted names with their references, etymologies and various notes.[75]

Description of new species

The International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology/International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (IJSB/IJSEM) is a peer reviewed journal which acts as the official international forum for the publication of new prokaryotic taxa. If a species is published in a different peer review journal, the author can submit a request to IJSEM with the appropriate description, which if correct, the new species will be featured in the Validation List of IJSEM.

Distribution

Microbial culture collections are depositories of strains which aim to safeguard them and to distribute them. The main ones being:[72]

| Collection Initialism | Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection

|

Manassas, Virginia

|

| NCTC | National Collection of Type Cultures | Public Health England, United Kingdom |

| BCCM | Belgium Coordinated Collection of Microorganisms | Ghent, Belgium |

| CIP | Collection d'Institut Pasteur | Paris, France |

| DSMZ | Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen

|

Braunschweig, Germany |

| JCM | Japan Collection of Microorganisms | Saitama, Japan

|

| NCCB | Netherlands Culture Collection of Bacteria | Utrecht, Netherlands |

| NCIMB | National Collection of Industrial, Food and Marine Bacteria | Aberdeen, Scotland |

| ICMP | International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants | Auckland, New Zealand |

| TBRC | Thailand Bioresource Research Center | Pathumthani, Thailand

|

| CECT | Spanish Type Culture Collection | Valencia, Spain |

Analyses

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2011) |

Bacteria were at first classified based solely on their shape (vibrio, bacillus, coccus etc.), presence of endospores, gram stain, aerobic conditions and motility. This system changed with the study of metabolic phenotypes, where metabolic characteristics were used.

Several identification methods exists:[72]

- Phenotypic analyses

- fatty acid analyses

- Growth conditions (Agar plate, Biolog multiwell plates)

- Genetic analyses

- DNA-DNA hybridization

- DNA profiling

- Sequence

- GC ratios

- Phylogenetic analyses

- 16S-based phylogeny

- phylogeny based on other genes

- Multi-gene sequence analysis

- Whole-genome sequence based analysis

New species

The minimal standards for describing a new species depend on which group the species belongs to. c.f.[80]

Candidatus

Candidatus is a component of the

Species concept

Bacteria divide asexually and for the most part do not show regionalisms ("

The number of named species of bacteria and archaea (approximately 13,000)[81] is surprisingly small considering their early evolution, genetic diversity and residence in all ecosystems. The reason for this is the differences in species concepts between the bacteria and macro-organisms, the difficulties in growing/characterising in pure culture (a prerequisite to naming new species, vide supra) and extensive horizontal gene transfer blurring the distinction of species.[82]

The most commonly accepted definition is the polyphasic species definition, which takes into account both phenotypic and genetic differences.[83] However, a quicker diagnostic ad hoc threshold to separate species is less than 70% DNA–DNA hybridisation,[84] which corresponds to less than 97% 16S DNA sequence identity.[85] It has been noted that if this were applied to animal classification, the order primates would be a single species.[86] For this reason, more stringent species definitions based on whole genome sequences have been proposed.[87]

Pathology vs. phylogeny

Ideally, taxonomic classification should reflect the evolutionary history of the taxa, i.e. the phylogeny. Although some exceptions are present when the phenotype differs amongst the group, especially from a medical standpoint. Some examples of problematic classifications follow.

Escherichia coli: overly large and polyphyletic

In the family Enterobacteriaceae of the class Gammaproteobacteria, the species in the genus Shigella (S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, S. sonnei) from an evolutionary point of view are strains of the species Escherichia coli (polyphyletic), but due to genetic differences cause different medical conditions in the case of the pathogenic strains.[88] Confusingly, there are also E. coli strains that produce Shiga toxin known as STEC.

Escherichia coli is a badly classified species as some strains share only 20% of their genome. Being so diverse it should be given a higher taxonomic ranking.[89] However, due to the medical conditions associated with the species, it will not be changed to avoid confusion in medical context.

Bacillus cereus group: close and polyphyletic

In a similar way, the Bacillus species (=phylum

Yersinia pestis: extremely recent species

Yersinia pestis is in effect a strain of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, but with a pathogenicity island that confers a drastically different pathology (Black plague and tuberculosis-like symptoms respectively) which arose 15,000 to 20,000 years ago.[91]

Nested genera in Pseudomonas

In the gammaproteobacterial order Pseudomonadales, the genus Azotobacter and the species Azomonas macrocytogenes are actually members of the genus Pseudomonas, but were misclassified due to nitrogen fixing capabilities and the large size of the genus Pseudomonas which renders classification problematic.[76][92][93] This will probably rectified in the close future.

Nested genera in Bacillus

Another example of a large genus with nested genera is the genus Bacillus, in which the genera Paenibacillus and Brevibacillus are nested clades.[94] There is insufficient genomic data at present to fully and effectively correct taxonomic errors in Bacillus.

Agrobacterium: resistance to name change

Based on molecular data it was shown that the genus Agrobacterium is nested in Rhizobium and the Agrobacterium species transferred to the genus Rhizobium (resulting in the following comp. nov.: Rhizobium radiobacter (formerly known as A. tumefaciens), R. rhizogenes, R. rubi, R. undicola and R. vitis)[95] Given the plant pathogenic nature of Agrobacterium species, it was proposed to maintain the genus Agrobacterium[96] and the latter was counter-argued[97]

Nomenclature

Taxonomic names are written in italics (or underlined when handwritten) with a majuscule first letter with the exception of epithets for species and subspecies. Despite it being common in zoology, tautonyms (e.g. Bison bison) are not acceptable and names of taxa used in zoology, botany or mycology cannot be reused for Bacteria (Botany and Zoology do share names).

Nomenclature is the set of rules and conventions which govern the names of taxa. The difference in nomenclature between the various kingdoms/domains is reviewed in.[98]

For Bacteria, valid names must have a Latin or Neolatin name and can only use basic latin letters (w and j inclusive, see

When

For etymologies of names consult LPSN.

Rules for higher taxa

For the Prokaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea) the rank kingdom is not used[101] (although some authors refer to phyla as kingdoms[72])

If a new or amended species is placed in new ranks, according to Rule 9 of the Bacteriological Code the name is formed by the addition of an appropriate suffix to the stem of the name of the type genus.

| Rank | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genus | Elusimicrobium | |

| Subtribe (disused) | -inae | (Elusimicrobiinae) |

| Tribe (disused) | -eae | (Elusimicrobiieae) |

| Subfamily | -oideae | (Elusimicrobioideae) |

| Family | -aceae | Elusimicrobiaceae |

| Suborder | -ineae | (Elusimicrobineae) |

| Order | -ales | Elusimicrobiales |

| Subclass | -idae | (Elusimicrobidae) |

| Class | -ia | Elusimicrobia |

| Phylum | -ota | Elusimicrobiota |

Phyla endings

Until 2021, phyla were not covered by the

Under the new rules, the name of a phylum is derived from the type genus:

- Acidobacteriota (from Acidobacterium)

- Actinomycetota (from Actinomyces)

- Aquificota (from Aquifex)

- Armatimonadota (from Armatimonas)

- Atribacterota (from Atribacter)

- Bacillota (from Bacillus)

- Bacteroidota (from Bacteroides)

- Balneolota (from Balneola)

- Bdellovibrionota (from Bdellovibrio)

- Caldisericota (from Caldisericum)

- Calditrichota (from Caldithrix)

- Campylobacterota (from Campylobacter)

- Chlamydia)

- Chlorobiota (from Chlorobium)

- Chloroflexus)

- Chrysiogenes)

- Coprothermobacterota (from Coprothermobacter)

- Deferribacterota (from Deferribacter)

- Deinococcota (from Deinococcus)

- Dictyoglomus)

- Elusimicrobiota (from Elusimicrobium)

- Fibrobacterota (from Fibrobacterota)

- Fusobacteriota (from Fusobacterium)

- Gemmatimonadota (from Gemmatimonas)

- Ignavibacteriota (from Ignavibacterium)

- Kiritimatiellota (from Kiritimatiella)

- Lentisphaerota (from Lentisphaera)

- Mycoplasmatota (from Mycoplasma)

- Myxococcota (from Myxococcus)

- Nitrospinota (from Nitrospina)

- Nitrospirota (from Nitrospira)

- Planctomycetota (from Planctomyces)

- Pseudomonadota (from Pseudomonas)

- Rhodothermota (from Rhodothermus)

- Spirochaetota (from Spirochaeta)

- Synergistes)

- Thermodesulfobacterium)

- Thermomicrobiota (from Thermomicrobium)

- Thermotogota (from Thermotoga)

- Verrucomicrobiota (from Verrucomicrobium)

Names after people

Several species are named after people, either the discoverer or a famous person in the field of microbiology, for example Salmonella is after D.E. Salmon, who discovered it (albeit as "Bacillus typhi"[105]).[106]

For the generic epithet, all names derived from people must be in the female nominative case, either by changing the ending to -a or to the diminutive -ella, depending on the name.[100]

For the specific epithet, the names can be converted into either adjectival form (adding -nus (m.), -na (f.), -num (n.) according to the gender of the genus name) or the genitive of the Latinised name.[100]

Names after places

Many species (the specific epithet) are named after the place they are present or found (e.g. Thiospirillum jenense). Their names are created by forming an adjective by joining the locality's name with the ending -ensis (m. or f.) or ense (n.) in agreement with the gender of the genus name, unless a classical Latin adjective exists for the place. However, names of places should not be used as nouns in the genitive case.[100]

Vernacular names

Despite the fact that some hetero/homogeneus colonies or biofilms of bacteria have names in English (e.g. dental plaque or Star jelly), no bacterial species has a vernacular/trivial/common name in English.

For names in the singular form, plurals cannot be made (

Customs are present for certain names, such as those ending in -monas are converted into -monad (one pseudomonad, two aeromonads and not -monades).

Bacteria which are the etiological cause for a disease are often referred to by the disease name followed by a describing noun (bacterium, bacillus, coccus, agent or the name of their phylum) e.g. cholera bacterium (Vibrio cholerae) or Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi), note also rickettsialpox (Rickettsia akari) (for more see[108]).

Treponema is converted into treponeme and the plural is treponemes and not treponemata.

Some unusual bacteria have special names such as Quin's oval (

Before the advent of molecular phylogeny, many higher taxonomic groupings had only trivial names, which are still used today, some of which are polyphyletic, such as Rhizobacteria. Some higher taxonomic trivial names are:

- Blue-green algae are members of the phylum "Cyanobacteria"

- Green non-sulfur bacteria are members of the phylum Chloroflexota

- Green sulfur bacteria are members of the Chlorobiota

- Purple bacteria are some, but not all, members of the phylum Pseudomonadota

- Purple sulfur bacteria are members of the order Chromatiales

- low G+C Gram-positive bacteria are members of the phylum Bacillota, regardless of GC content

- high G+C Gram-positive bacteria are members of the phylum Actinomycetota, regardless of GC content

- Rhizobia are members of various genera of Pseudomonadota

- Lactic acid bacteria are members of the order Lactobacillales

- Coryneform bacteria are members of the family Corynebacteriaceae

- Fruiting gliding bacteria or myxobacteria are members of the phylum Myxococcota

- Enterics are members of the order Enterobacteriales (although the term is avoided if they do not live in the intestines, such as Pectobacterium)

- Acetic acid bacteria are members of the family Acetobacteraceae

Terminology

- The abbreviation for species is sp. (plural spp.) and is used after a generic epithet to indicate a species of that genus. Often used to denote a strain of a genus for which the species is not known either because has the organism has not been described yet as a species or insufficient tests were conducted to identify it. For example Halomonas sp. GFAJ-1

- If a bacterium is known and well-studied but not culturable, it is given the term Candidatus in its name

- A basonym is original name of a new combination, namely the first name given to a taxon before it was reclassified

- A synonym is an alternative name for a taxon, i.e. a taxon was erroneously described twice

- When a taxon is transferred it becomes a new combination (comb. nov.) or new name (nom. nov.)

- paraphyly, monophyly, and polyphyly

See also

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Woese, 1987)

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Gupta, 2001)

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Cavalier-Smith, 2002)

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Rappe and Giovanoni, 2003)

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Battistuzzi et al.,2004)

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Ciccarelli et al., 2006)

- Branching order of bacterial phyla after ARB Silva Living Tree

- Branching order of bacterial phyla (Genome Taxonomy Database, 2018)

- Bacterial phyla, a complicated classification

- List of Archaea genera

- List of Bacteria genera

- List of bacterial orders

- List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names

- List of sequenced archaeal genomes

- List of sequenced prokaryotic genomes

- List of clinically important bacteria

- Species problem

- Evolutionary grade

- Cryptic species complex

- Synonym (taxonomy)

- Taxonomy

- LPSN, list of accepted bacterial and archaeal names

- Cyanobacteria, a phylum of common bacteria but poorly classified at present

- Human microbiome project

- Microbial ecology

References

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1735). Systemae Naturae, sive regna tria naturae, systematics proposita per classes, ordines, genera & species.

- ^ PMID 2112744.

- PMID 786250.

- .

- .

- S2CID 186209549.

- ^ a b c Murray, R.G.E., Holt, J.G. (2005). The history of Bergey's Manual. In: Garrity, G.M., Boone, D.R. & Castenholz, R.W. (eds., 2001). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed., vol. 1, Springer-Verlag, New York, p. 1-14. link. [See p. 2.]

- ^ Pot, B., Gillis, M., and De Ley, J., The genus Aquaspirillum. In: Balows, A., Trüper, H.G., Dworkin, M., Harder, W., Schleifer, K.-H. (Eds.). The prokaryotes, 2nd ed, vol. 3. Springer-Verlag. New York. 1991

- ^ "Etymology of the word "bacteria"". Online Etymology dictionary. Archived from the original on 18 November 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-144-00186-3– via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Von Nägeli, C. (1857). Caspary, R. (ed.). "Bericht über die Verhandlungen der 33. Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte, gehalten in Bonn von 18 bis 24 September 1857" [Report on the negotiations on the 33rd Meeting of German Natural Scientists and Physicians, held in Bonn, 18 to 24 September 1857]. Botanische Zeitung (in German). 15: 749–776 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Pacini, F.: Osservazione microscopiche e deduzioni patologiche sul cholera asiatico. Gazette Medicale de Italiana Toscano Firenze, 1854, 6, 405-412.

- ^ a b Ehrenberg, C. G. (1835). "Dritter Beitrag zur Erkenntniss grosser Organisation in der Richtung des kleinsten Raumes". Physikalische Abhandlungen der Koeniglichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin aus den Jahren 1833-1835, pp. 143-336.

- ^ Ehrenberg, C. G. (1830). "Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Organization der Infusorien und ihrer geographischen Verbreitung besonders in Sibirien". Abhandlungen der Koniglichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1832, pp. 1–88.

- .

- ^ Chatton, É. (1925). "Pansporella perplexa: Réflexions sur la biologie et la phylogénie des protozoaires". Annales des Sciences Naturelles. 10 (VII): 1–84.

- ^ Smith, Erwin F. (1905). Nomenclature and Classification in Bacteria in Relation to Plant Diseases, Vol. 1.

- ^ Vuillemin (1913). "Genera Schizomycetum". Annales Mycologici, Vol. 11, pp. 512–527.

- ^ Cohn, Ferdinand (1875). "Untersuchungen uber Bakterien, II". Beitrage zur Biologie der Pfanzen, Vol. 1: pp. 141–207

- ^ Stanier and van Neil (1941). "The main outlines of bacterial classification". Journal of Bacteriology, Vol. 42, pp. 437– 466

- ^ Bisset (1962). Bacteria, 2nd ed.; London: Livingston.

- ^ Migula, Walter (1897). System der Bakterien. Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer.

- ^ Orla-Jensen (1909). "Die Hauptlinien des naturalischen Bakteriensystems nebst einer Ubersicht der Garungsphenomene". Zentr. Bakt. Parasitenk., Vol. II, No. 22, pp. 305–346

- ^ Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (1925). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co. (with many subsequent editions).

- PMID 16558720– via National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ^ Cohn, Ferdinand (1872 a). "Organismen in der Pockenlymphe". Virchow (ed.), Archiv, Vol. 55, p. 237.

- ^ Cohn, Ferdinand (1872 b) "Untersuchungen ilber Bakterien". Beitrage zur Biologie der Pflanzen Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 136.

- ^ Detoni, J. B.; Trevisan, V. (1889). "Schizomycetaceae". Saccardo (ed.), Sylloge Fungorum, Vol. 8, p. 923.

- PMID 16558735.

- PMID 16561459.

- ^ Prévot, A. R. (1958). Manuel de classification et détermination des bactéries anaérobies. Paris: Masson.

- ^ Prévot, A. R. (1963). Bactéries in Précis de Botanique. Paris: Masson.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1735). Systemae Naturae, sive regna tria naturae, systematics proposita per classes, ordines, genera & species.

- ^ Haeckel, E. (1866). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Reimer, Berlin.

- ^ Chatton, É. (1925). "Pansporella perplexa. Réflexions sur la biologie et la phylogénie des protozoaires". Annales des Sciences Naturelles - Zoologie et Biologie Animale. 10-VII: 1–84.

- S2CID 84634277.

- PMID 5762760.

- PMID 2112744.

- S2CID 6557779.

- PMID 25923521.

- .

- ^ a b George M. Garrity: Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. 2. Auflage. Springer, New York, 2005, Volume 2: The Proteobacteria, Part B: The Gammaproteobacteria

- ^ MURRAY (R.G.E.): The higher taxa, or, a place for everything...? In: N.R. KRIEG and J.G. HOLT (ed.) Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 1, The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1984, p. 31-34

- S2CID 1615592.

- S2CID 4343245.

- PMID 9618502.

- S2CID 30541897.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2010. Virus. Encyclopedia of Earth. Editors: Cutler Cleveland and Sidney Draggan

- PMID 16754611.

- PMID 8177167.

- S2CID 27788891.

- PMID 432104.

- ^ Holland L. (22 May 1990). "Woese, Carl in the forefront of bacterial evolution revolution". Scientist. 4 (10).

- PMID 2439888.

- PMID 12149517.

- ^ PMID 11837318.

- ^ PMID 16834776.

- ^ PMID 19946133.

- PMID 20194428.

- PMID 20194428.

- PMID 19085327.

- PMID 17513883.

- PMID 21356104.

- PMID 9841678.

- PMID 9733652.

- S2CID 30541897.

- PMID 2452957.

- S2CID 4273843.

- PMID 6587394.

- .

- S2CID 4413304.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-232460-1.

- ^ PMID 21089234.

- OCLC 262687428.

- .

- ^ PMID 20553550.

- PMID 2041798.

- PMID 19004872.

- PMID 17947321.

- .

- ^ "Number of published names".

- PMID 17062409.

- S2CID 41706247.

- PMID 3213314.

- .

- PMID 9206017.

- PMID 30285620.

- PMID 12361912.

- PMID 25780495.

- PMID 15297521.

- PMID 10570195.

- PMID 18048745.

- PMID 15133068.

- PMID 12807189.

- PMID 11211278.

- PMID 13130068.

- PMID 13130069.

- ^ C. Jeffrey. 1989. Biological Nomenclature, 3rd ed. Edward Arnold, London, 86 pp.

- ^ app. 9 of BC https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8808/

- ^ a b c d "Help! Latin! How to avoid the most common mistakes while giving Latin names to newly discovered prokaryotes". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- .

- .

- ^ .

- S2CID 239887308.

- ^ SCHROETER (J.). In: F. COHN (ed.), Kryptogamenflora von Schlesien. Band 3, Heft 3, Pilze. J.U. Kern's Verlag, Breslau, 1885-1889, pp. 1-814.

- .

- ^ R. E. BUCHANAN, Taxonomy, Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1955.9:1-20. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.mi.09.100155.000245

- ^ ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/taxonomy/