Fatty liver disease

Parts of this article (those related to the use of the new 2023 nomenclature) need to be updated. (November 2023) |

| Fatty liver | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hepatic steatosis |

Wilson disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis[3] | |

| Treatment | Avoiding alcohol, weight loss[3][1] |

| Prognosis | Good if treated early[3] |

| Frequency | NAFLD: 30% (Western countries)[2] ALD: >90% of heavy drinkers[4] |

Fatty liver disease (FLD), also known as hepatic steatosis and steatotic liver disease (SLD), is a condition where excess fat builds up in the liver.[1] Often there are no or few symptoms.[1][2] Occasionally there may be tiredness or pain in the upper right side of the abdomen.[1] Complications may include cirrhosis, liver cancer, and esophageal varices.[1][3]

The main subtypes of fatty liver disease are

The primary risks include alcohol, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.[1][3] Other risk factors include certain medications such as glucocorticoids, and hepatitis C.[1] It is unclear why some people with NAFLD develop simple fatty liver and others develop nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is associated with poorer outcomes.[1] Diagnosis is based on the medical history supported by blood tests, medical imaging, and occasionally liver biopsy.[1]

Treatment of NAFLD is generally by dietary changes and exercise to bring about weight loss.[1] In those who are severely affected, liver transplantation may be an option.[1] More than 90% of heavy drinkers develop fatty liver while about 25% develop the more severe alcoholic hepatitis.[4] NAFLD affects about 30% of people in Western countries and 10% of people in Asia.[2] NAFLD affects about 10% of children in the United States.[1] It occurs more often in older people and males.[3][6]

Classification

Fatty liver disease was classified into:

-

- simple fatty liver

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

- Alcoholic liver disease (ALD).[1]

In 2023, a new nomenclature was chosen,[5][7] with the classifications including:

- Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), including:

- Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis(MASH)

- Metabolic and alcohol associated liver disease (metALD). Describes those with MASLD who consume greater amounts of alcohol per week but not enough to be categorized as ALD)

- Alcohol-associated liver disease(ALD)

- Specific aetiology SLD (including drug-induced, monogenic diseases and others)

Signs and symptoms

Often there are no or few symptoms.[1] Occasionally there may be tiredness or pain in the upper right side of the abdomen.[1]

Complications

Fatty liver can develop into hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis or liver cancer.[8] For people affected by NAFLD, the 10-year survival rate was about 80%. The rate of progression of fibrosis is estimated to be one per 7 years in NASH and one per 14 years in NAFLD, with an increasing speed.[9][10] There is a strong relationship between these pathologies and metabolic illnesses (diabetes type II, metabolic syndrome). These pathologies can also affect non-obese people, who are then at a higher risk.[8]

Less than 10% of people with cirrhotic alcoholic FLD will develop hepatocellular carcinoma,[11] the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults, but up to 45% people with NASH without cirrhosis can develop hepatocellular carcinoma.[12]

The condition is also associated with other diseases that influence fat metabolism.[13]

Causes

Fatty liver (FL) is commonly associated with metabolic syndrome (diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia), but can also be due to any one of many causes:[14][15]

- Alcohol

- Alcohol use disorderis one of the causes of fatty liver due to production of toxic metabolites like aldehydes during metabolism of alcohol in the liver. This phenomenon most commonly occurs with chronic alcohol use disorder.

- Metabolic

- abetalipoproteinemia, glycogen storage diseases, Weber–Christian disease, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, lipodystrophy

- Nutritional

- bacterial overgrowth

- Drugs and toxins

- )

- Other

- celiac disease,[17] inflammatory bowel disease, HIV, hepatitis C (especially genotype 3), and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency[18]

Pathology

The fatty change represents the

Defects in fatty acid metabolism are responsible for pathogenesis of FLD, which may be due to imbalance in energy consumption and its combustion, resulting in lipid storage, or can be a consequence of peripheral resistance to insulin, whereby the transport of fatty acids from adipose tissue to the liver is increased.[13][22] Impairment or inhibition of receptor molecules (

Severe fatty liver is sometimes accompanied by

Liver disease with extensive inflammation and a high degree of steatosis often progresses to more severe forms of the disease.

The progression to cirrhosis may be influenced by the amount of fat and degree of steatohepatitis and by a variety of other sensitizing factors. In alcoholic FLD, the transition to cirrhosis related to continued alcohol consumption is well-documented, but the process involved in non-alcoholic FLD is less clear.

Diagnosis

| Flow chart for diagnosis[15] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‡ Criteria for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: consumption of ethanol less than 20 g/day for women and 30 g/day for men[26] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Most individuals are asymptomatic and are usually discovered incidentally because of abnormal liver function tests or hepatomegaly noted in unrelated medical conditions. Elevated liver enzymes are found in as many as 50% of patients with simple steatosis.[27]: 1794 The serum alanine transaminase (ALT) level usually is greater than the aspartate transaminase (AST) level in the nonalcoholic variant and the opposite in alcoholic FLD (AST:ALT more than 2:1). Simple blood tests may help to determine the magnitude of the disease by assessing the degree of liver fibrosis.[28] For example, AST-to-platelets ratio index (APRI score) and several other scores, calculated from the results of blood tests, can detect the degree of liver fibrosis and predict the future formation of liver cancer.[29]

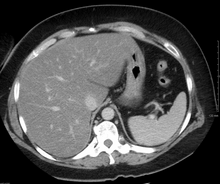

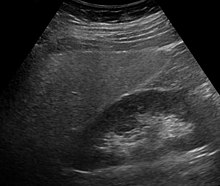

Imaging studies are often obtained during the evaluation process.

Treatment

Decreasing caloric intake by at least 30% or by approximately 750–1,000 kcal/day results in improvement in hepatic steatosis.

Bariatric surgery, while not recommended in 2017 as a treatment for FLD alone, has been shown to revert FLD, NAFLD, NASH and advanced steatohepatitis in over 90% of people who have undergone this surgery for the treatment of obesity.[8][34]

In the case of long-term total-parenteral-nutrition-induced fatty liver disease, choline has been shown to alleviate symptoms.[35][36][37] This may be due to a deficiency in the methionine cycle.[38]

Epidemiology

NAFLD affects about 30% of people in Western countries and 10% of people in Asia.[2]

In the United States rates are around 35% with about 7% having the severe form NASH.

In the study

After the

In animals

Fatty liver disease can occur in pets such as reptiles (particularly

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease & NASH". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ PMID 29085205.

- ^ PMID 28723021.

- ^ PMID 21731902.

- ^ S2CID 259260747.

- ^ PMID 23826593.

- ^ "A Liver Disease Gets a New Name, Diagnostic Criteria". Medscape. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ PMID 28714183.

- PMID 24768810.

- ^ S2CID 31345431.

- PMID 15908310.

- PMID 28052624.

- ^ PMID 16603729.

- ^ PMID 11961152.

- ^ PMID 16770927.

- S2CID 33505288.

- PMID 26711682.

- S2CID 26068505.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-4563-6.[page needed]

- PMID 16012941.

- PMID 15670663.

- PMID 15277442.

- PMID 9547102.

- PMID 14991537.

- S2CID 7708476.

- PMID 15795412.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-0245-1. Retrieved 4 July 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- PMID 28572039.

- PMID 30106985.

- ^ Miles DA, Levi CS, Uhanova J, Cuvelier S, Hawkins K, Minuk GY. Pocket-Sized Versus Conventional Ultrasound for Detecting Fatty Infiltration of the Liver. Dig Dis Sci. 2020 Jan;65(1):82-85. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05752-x. Epub 2019 Aug 2. PMID 31376083.

- ^ Costantino A, Piagnani A, Caccia R, Sorge A, Maggioni M, Perbellini R, Donato F, D'Ambrosio R, Sed NPO, Valenti L, Prati D, Vecchi M, Lampertico P, Fraquelli M. Reproducibility and accuracy of a pocket-size ultrasound device in assessing liver steatosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2023 Nov 27:S1590-8658(23)01032-0. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2023.11.014. Epub ahead of print. PMID 38016894.

- PMID 26314479.

- PMID 28652891.

- ^ Fatty Liver at eMedicine

- S2CID 20227016.

- PMID 1551541.

- PMID 11531217.

- PMID 20656090.

- ^ S2CID 232018678.

- S2CID 22475943.

- ^ Sarah Boseley (12 April 2019). "Experts warn of fatty liver disease 'epidemic' in young people". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ SPINK HEALTH (11 April 2019). "Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease found in large numbers of teenagers and young adults". EurekAlert! (Press release). American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- PMID 35276911..

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ Liu, Y.L.; Patman, G.L.; Leathart, J.B.; Piguet, A.C.; Burt, A.D.; Dufour, J.F.; Day, C.P.; Daly, A.K.; Reeves, H.L.; Anstee, Q.M. Carriage of the PNPLA3 rs738409 C >G polymorphism confers an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 75–81.

- ^ Eslam, M.; Valenti, L.; Romeo, S. Genetics and epigenetics of NAFLD and NASH: Clinical impact. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 268–279.

- ^ Lock B (8 August 2017). "Hepatic Lipidosis (Fatty Liver Disease) in Reptiles". Vin.com. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Fatty Liver Disease in Birds". Animal House of Chicago. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Fatty Liver Disease in Cats". PetMD. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- PMID 32699301.

- PMID 33608323.

External links

- Photo at Atlas of Pathology

- Healthdirect