History of anarchism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

According to different scholars, the history of anarchism either goes back to ancient and prehistoric

Alongside

Anarchism played a historically prominent role during the

In the 1960s, anarchism re-emerged as a global political and cultural force. In association with the

Background

Τhere has been some controversy over the

The three most common forms of defining anarchism are the "etymological" (an-archei, without a ruler, but anarchism is not merely a negation); the "anti-statism" (while this seems to be pivotal, it certainly does not describe the essence of anarchism); and the "anti-authoritarian" definition (denial of every kind of authority, which over-simplifies anarchism).[6][7] Along with the definition debates, the question of whether it is a philosophy, a theory or a series of actions complicates the issue.[8] Philosophy professor Alejandro de Agosta proposes that anarchism is "a decentralized federation of philosophies as well as practices and ways of life, forged in different communities and affirming diverse geohistories".[9]

Precursors

Prehistoric and ancient era

Many scholars of anarchism, including anthropologists Harold Barclay and David Graeber, claim that some form of anarchy dates back to prehistory. The longest period of human existence, that before the recorded history of human society, was without a separate class of established authority or formal political institutions.[10][11] Long before anarchism emerged as a distinct perspective, humans lived for thousands of years in self-governing societies without a special ruling or political class.[12] It was only after the rise of hierarchical societies that anarchist ideas were formulated as a critical response to, and a rejection of, coercive political institutions and hierarchical social relationships.[13]

Some convictions and ideas deeply held by modern anarchists were first expressed in

Among the ancient precursors of anarchism are often ignored movements within ancient

Middle Ages

In Persia during the Middle Ages a

In Europe, Christianity was overshadowing all aspects of life. The Brethren of the Free Spirit was the most notable example of heretic belief that had some vague anarchistic tendencies. They held anticleric sentiments and believed in total freedom. Even though most of their ideas were individualistic, the movement had a social impact, instigating riots and rebellions in Europe for many years.[31] Other anarchistic religious movements in Europe during the Middle Ages included the Hussites and Adamites.[32]

20th-century historian James Joll described anarchism as two opposing sides. In the Middle Ages, zealotic and ascetic religious movements emerged, which rejected institutions, laws and the established order. In the 18th century another anarchist stream emerged based on rationalism and logic. These two currents of anarchism later blended to form a contradictory movement that resonated with a very broad audience.[33]

Renaissance and early modern era

With the spread of the

Some

In the

The

Early anarchism

Developments of the 18th century

Modern anarchism grew from the secular and humanistic thought of the Enlightenment. The scientific discoveries that preceded the Enlightenment gave thinkers of the time confidence that humans can reason for themselves. When nature was tamed through science, society could be set free. The development of anarchism was strongly influenced by the works of Jean Meslier, Baron d'Holbach, whose materialistic worldview later resonated with anarchists, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, especially in his Discourse on Inequality and arguments for the moral centrality of freedom. Rousseau affirmed the goodness in the nature of men and viewed the state as fundamentally oppressive. Denis Diderot's Supplément au voyage de Bougainville (The Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville) was also influential.[39][40]

The

The debate over the effects of the French Revolution on the anarchist cause continues to this day. To anarchist historian

Proudhon and Stirner

Frenchman

Mutualists would later play an important role in the

In Spain,

An influential form of individualist anarchism called egoism or egoist anarchism, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, German philosopher Max Stirner.[60][61] Stirner's The Ego and Its Own (German: Der Einzige und sein Eigentum; also translated as The Individual and his Property or The Unique and His Property), published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy.[61] Stirner was critical of capitalism as it creates class warfare where the rich will exploit the poor, using the state as its tool.[62] He also rejected religions, communism and liberalism, as all of them subordinate individuals to God, a collective, or the state.[63] According to Stirner the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire, without regard for God, state, or morality.[64] He held that society does not exist, but "the individuals are its reality".[65] Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will, which proposed as a form of organisation in place of the state.[66][67] Egoist anarchists claimed that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals.[68] Stirner was proposing an individual rebellion, which would not seek to establish new institutions nor anything resembling a state.[63]

Revolutions of 1848

Europe was shocked by another revolutionary wave in 1848 which started once again in Paris. The new government, consisting mostly of Jacobins, was backed by the working class but failed to implement meaningful reforms. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin were involved in the events of 1848. The failure of the revolution shaped Proudhon's views. He became convinced that a revolution should aim to destroy authority, not grasp power. He saw capitalism as the root of social problems and government, using political tools only, as incapable of confronting the real issues.[69] The course of events of 1848, radicalised Bakunin who, due to the failure of the revolutions, lost his confidence in any kind of reform.[70]

Other anarchists active in the 1848 Revolution in France include Anselme Bellegarrigue, Ernest Coeurderoy and the early anarcho-communist Joseph Déjacque, who was the first person to call himself a libertarian.[71] Unlike Proudhon, Déjacque argued that "it is not the product of his or her labour that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature".[72] Déjacque was also a critic of Proudhon's mutualist theory and anti-feminist views.[10] Returning to New York, he was able to serialise his book in his periodical Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement social.[73] The French anarchist movement, though self-described as "mutualists", started gaining pace during 1860s as workers' associations began to form.[74]

Classical anarchism

The decades of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries constitute the

First International and Paris Commune

In 1864, the creation of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA, also called the "First International") united diverse revolutionary currents - including socialist Marxists, trade unionists, communists and anarchists.[84][85] Karl Marx, a leading figure of the International, became a member of its General Council.[86][87]

Four years later, in 1868,

Meanwhile, an uprising after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 to 1871 led to the formation of the Paris Commune in March 1871. Anarchists had a prominent role in the Commune,[92] next to

In 1872, the conflict between Marxists and anarchists climaxed. Marx had, since 1871, proposed the creation of a political party, which anarchists found to be an appalling and unacceptable prospect. Various groups (including Italian sections, the Belgian Federation and the

Emergence of anarcho-communism

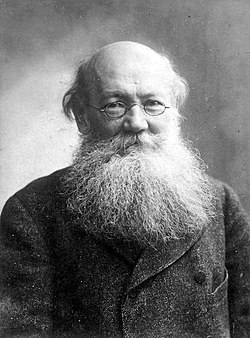

With the aid of Peter Kropotkin's optimism and persuasive writing, anarcho-communism became the major anarchist current in Europe and abroad—except in Spain where anarcho-syndicalism prevailed.[101] The theoretical work of Kropotkin and Errico Malatesta grew in importance later as it expanded and developed pro-organisationalist and insurrectionary anti-organisationalist sections.[100] Kropotkin elaborated on the theory behind the revolution of anarcho-communism saying, "it is the risen people who are the real agent and not the working class organised in the enterprise (the cells of the capitalist mode of production) and seeking to assert itself as labour power, as a more 'rational' industrial body or social brain (manager) than the employers".[100]

Organised labour and syndicalism

Due to a high influx of European immigrants, Chicago was the centre of the American anarchist movement during the 19th century. On

The French

In 1907, the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam gathered delegates from most European countries, the United States, Japan and Latin America.[116] A central debate concerned the relation between anarchism and trade unionism.[117] Errico Malatesta and Pierre Monatte strongly disagreed on this issue. Monatte thought that syndicalism was revolutionary and would create the conditions for a social revolution, while Malatesta did not consider syndicalism by itself sufficient.[118][119] He thought the trade-union movement was reformist and even conservative, citing the phenomenon of professional union officials as essentially bourgeois and anti-worker. Malatesta warned that the syndicalist aims were of perpetuating syndicalism itself, whereas anarchists must always have anarchy as their end goal and consequently must refrain from committing to any particular method of achieving it.[120]

In Spain, syndicalism had grown significantly during the 1880s but the first anarchist related organisations didn't flourish. In 1910 however, the

By the early 20th century, revolutionary syndicalism had spread across the world, from Latin America to Eastern Europe and Asia, with most of its activity then taking place outside of Western Europe.[124]

Propaganda of the deed

The use of revolutionary

Paul Brousse, a medical doctor and active militant of violent insurrection, popularised the actions of propaganda of the deed.[131][74] In the United States, Johann Most advocated publicising violent acts of retaliation against counter-revolutionaries because "we preach not only action in and for itself, but also action as propaganda".[132] Russian anarchist-communists employed terrorism and illegal acts in their struggle.[133] Numerous heads of state were assassinated or attacked by members of the anarchist movement.[134] In 1901, the Polish-American anarchist Leon Czolgosz assassinated the president of the United States, William McKinley. Emma Goldman, who was erroneously suspected of being involved, expressed some sympathy for Czolgosz and incurred a great deal of negative publicity.[135] Goldman also supported Alexander Berkman in his failed assassination attempt of steel industrialist Henry Frick in the wake of the Homestead Strike, and she wrote about how these small acts of violence were incomparable to the deluge of violence regularly committed by the state and capital.[136] In Europe, a wave of illegalism (the embracement of a criminal way of life) spread throughout the anarchist movement, with Marius Jacob, Ravachol, intellectual Émile Henry and the Bonnot Gang being notable examples. The Bonnot Gang in particular justified illegal and violent behavior by claiming that they were "taking back" property that did not rightfully belong to capitalists.[137][138] In Russia, Narodnaya Volya ("People's Will" which was not an anarchist organisation but nevertheless drew inspiration from Bakunin's work), assassinated Tsar Alexander II in 1881 and gained some popular support. However, for the most part, the anarchist movement in Russia remained marginal in the following years.[139][140] In the Ottoman Empire, the Boatmen of Thessaloniki were a Bulgarian anarchist revolutionary organisation active 1898-1903.

As early as 1887, important figures in the anarchist movement distanced themselves from both illegalism and propaganda of the deed. Peter Kropotkin, for example, wrote in Le Révolté that "a structure based on centuries of history cannot be destroyed with a few kilos of dynamite".

By the end of the 19th century, it became clear that propaganda of the deed was not going to spark a revolution. Though it was employed by only a minority of anarchists, it gave anarchism a violent reputation and it isolated anarchists from broader social movements.[146] It was abandoned by the majority of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century.[147]

Revolutionary wave

Anarchists were involved in the

From the collapse of anarchism in the newly formed

During the

In

Rise of fascism

Italy saw the first struggles between anarchists and fascists.

In France, where the

In Germany, the Nazis crushed anarchism upon seizing power.[163] Apart from Spain, nowhere else could the anarchist movement provide a solid resistance to various fascist regimes throughout Europe.[179]

Spanish Revolution

The

In 1936, the

Anarchists of CNT-FAI faced a major dilemma after the coup had failed in July 1936: either continue their fight against the state or join the anti-fascist left-wing parties and form a government. They opted for the latter and by November 1936, four members of CNT-FAI became ministers in the government of the former trade unionist Francisco Largo Caballero. This was justified by CNT-FAI as a historical necessity since war was being waged, but other prominent anarchists disagreed, both on principle and as a tactical move.[190] In November 1936 the prominent anarcho-feminist Federica Montseny was installed as minister of Health—the first woman in Spanish history to become a cabinet minister.[191]

During the course of the events of the Spanish Revolution, anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the

The 1939 defeat of Republican Spain marked the end of anarchism's classical period.[193][194] In light of continual anarchist defeats, one can argue about the naivety of 19th-century anarchist thinking—the establishment of state and capitalism was too strong to be destroyed. According to political philosophy professor Ruth Kinna and lecturer Alex Prichard, it is uncertain whether these defeats were the result of a functional error within the anarchist theories, as New Left intellectuals suggested some decades later, or the social context that prevented the anarchists from fulfilling their ambitions. What is certain, though, is that their critique of state and capitalism ultimately proved right, as the world was marching towards totalitarianism and fascism.[195]

Anarchism in the colonial world

As empires and capitalism were expanding at the turn of the century, so was anarchism which soon flourished in Latin America, East Asia, South Africa and Australia.[196]

Anarchism found fertile ground in Asia and was the most vibrant ideology among other socialist currents during the first decades of 20th century. The works of European philosophers, especially Kropotkin's, were popular among revolutionary youth. Intellectuals tried to link anarchism to earlier philosophical currents in Asia, like Taoism,

Anarchism travelled to the

Anarchism travelled to Latin America through European immigrants. The most impressive presence was in Buenos Aires, but Havana, Lima, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, Santos, São Paulo as well saw the growth of anarchist pockets. Anarchists had a much larger impact on trade unions than their authoritarian left counterparts.[202][206] In Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, a strong anarcho-syndicalist current was formed—partly because of the rapid industrialisation of these countries. In 1905, anarchists took control of the Argentine Regional Workers' Federation (FORA) in Argentina, overshadowing social democrats. Likewise, in Uruguay, FORU was created by anarchists in 1905. These syndicates organised a series of general strikes in the following years. After this the success of the Bolsheviks, anarchism gradually declined in these three countries which had been the strongholds of anarchism in Latin America.[207] It is worth noting that the notion of imported anarchism in Latin America has been challenged, as slave rebellions appeared in Latin America before the arrival of European anarchists.[208]

Anarchists became involved in the anti-colonial national-independence struggles of the early 20th century. Anarchism inspired anti-authoritarian and egalitarian ideals among national independence movements, challenging the nationalistic tendencies of many national liberation movements.[209]

Individualist anarchism

In the United States

American anarchism has its roots in religious groups that fled Europe to escape

In the shade of individualism, there was also anarcho-Christianism as well as some socialist pockets, especially in Chicago.[217] It was after Chicago's bloody protests in 1886 when the anarchist movement became known nationwide. But anarchism quickly declined when it was associated with terrorist violence.[215][218]

An important concern for American individualist anarchism was free love. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women, for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[219] Openly bisexual radical Edna St. Vincent Millay and lesbian anarchist Margaret Anderson were prominent among them. Discussion groups organised by the Villagers were frequented by Emma Goldman, among others.[220]

A heated debate among American individualist anarchists of that era was the natural rights versus egoistic approaches. Proponents of naturals rights claimed that without them brutality would prevail, while egoists were proposing that there is no such right, it only restricted the individual. Benjamin Tucker, who tried to determine a scientific base for moral right or wrong, ultimately sided with the latter.[221]

The

In Europe and the arts

Post-war

Following the end of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, the anarchist movement was a "ghost" of its former self, as proclaimed by anarchist historian

In France, a wave of protests and demonstrations confronted the right-wing government of Charles de Gaulle in May 1968. Even though the anarchists had a minimal role, the events of May had a significant impact on anarchism.[242][243] There were huge demonstrations with crowds in some places reaching one million participants. Strikes were called in many major cities and towns involving seven million workers—all grassroots, bottom-up and spontaneously organised.[244] Various committees were formed at universities, lyceums, and in neighbourhoods, mostly having anti-authoritarian tendencies.[245] Slogans that resonated with libertarian ideas were prominent such as: "I take my desires for reality, because I believe in the reality of my desires."[246] Even though the spirit of the events leaned mostly towards libertarian communism, some authors draw a connection to anarchism.[247] The wave of protests eased when a 10% pay raise was granted and national elections were proclaimed. The paving stones of Paris were only covering some reformist victories.[248] Nevertheless, the 1968 events inspired a new confidence in anarchism as workers' management, self-determination, grassroots democracy, antiauthoritarianism, and spontaneity became relevant once more. After decades of pessimism 1968 marked the revival of anarchism, either as a distinct ideology or as a part of other social movements.[249]

Originally founded in 1957, The

As the ecological crisis was becoming a greater threat to the planet, Murray Bookchin developed a new wave of anarchist thought. In his social ecology theory, he argues that certain social practices and priorities threaten life on Earth. He goes further to identify the cause of such practises as social oppressions. He proposed libertarian municipalism, the involvement of people in political struggles in decentralized federated villages or towns.[254]

Contemporary anarchism

The anthropology of anarchism has changed in the contemporary era as the traditional lines or ideas of the 19th century have been abandoned. Most anarchists are now younger activists informed with feminist and ecological concerns. They are involved in

Mexico saw another uprising at the turn of the 21st century.

Anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist, and

According to anarchist scholar

References

- ^ a b Levy 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Levy 2010, p. 2.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Levy 2010, p. 4.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, p. 165.

- ^ Levy 2010, p. 6.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, pp. 27–29.

- ^ de Acosta 2009, p. 26.

- ^ de Acosta 2009, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f Graham 2005, pp. xi–xiv.

- ^ Ross 2019, p. ix.

- ^ Barclay 1990, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Barclay 1990, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 55.

- ^ Rapp 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Rapp 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Rapp 2012, pp. 45–46.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8476-7953-9.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 38.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 217.

- ^ Jun & Wahl 2010, pp. 68–70.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 68.

- ^ a b Fiala 2017.

- ^ Schofield 1999, p. 56.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 67.

- ^ a b Goodway 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible, PM Press, 2009, chapter 5.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 86.

- ^ Crone 2000, pp. 3, 21–25: Anarchist historian David Goodway is also convinced that the Muslim sects e Mu'tazilite and Najdite are part of anarchist history. (Interview in The Guardian 7 September 2011)

- German Peasants' Revolt by Thomas Munzer in 1525, and Münster rebellionin 1534"

- ^ Nettlau 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Joll 1975, p. 23.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 108–114.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, pp. 102–104 & 141.

- ^ Lehning 2003.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 102–104 & 389.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 43.

- ^ McKinley 2019, pp. 307–310.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, p. 102.

- ^ McKinley 2019, pp. 311–312.

- ^ McKinley 2019, p. 311.

- ^ McKinley 2019, p. 313.

- ^ Nettlau 1996, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 432.

- ^ Sheehan 2003, pp. 85–86.

- ^ McKinley 2019, pp. 308 & 310.

- ^ Adams 2001, p. 116.

- ^ McKinley 2019, p. 308.

- ^ Philip 2006.

- ^ McKinley 2019, p. 310.

- ^ McKinley 2019, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Firth 2019, p. 492.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 7 & 239.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 7.

- ^ a b Wilbur 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Edwards 1969, p. 33.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Britannica 2018, Anarchism in Spain.

- ^ a b Woodcock 1962, p. 357.

- ^ Goodway 2006, p. 99.

- ^ a b Leopold 2015.

- ^ McKinley 2019, p. 317.

- ^ a b McKinley 2019, p. 318.

- ^ Miller 1991, article.

- ^ Ossar 1980, p. 27: "What my might reaches is my property; and let me claim as property everything I feel myself strong enough to attain, and let me extend my actual property as far as 'I' entitle, that is, empower myself to take..."

- ^ Thomas 1985, p. 142.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 211, 229.

- ^ Carlson 1972.

- ^ McKinley 2019, pp. 318–320.

- ^ McKinley 2019, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 434.

- ^ a b Graham 2005.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 434–435.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 436.

- ^ a b Levy 2004, pp. 337–338.

- ^ Avrich 1982, p. 441, "... the classical age of anarchism, bounded by the Paris Commune and the Spanish Civil War ..."

- ^ Levy & Newman 2019, p. 12.

- ^ Cornell 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Levy 2004, p. 330.

- ^ Moya 2015, p. 327.

- ^ Moya 2015, p. 331.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 301–303.

- ^ Graham 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 325–327.

- ^ Forman 2009, p. 1755.

- ^ a b Dodson 2002, p. 312.

- ^ a b Thomas 1985, p. 187.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 280; Graham 2019.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 328–331.

- ^ Engel 2000, p. 140.

- ^ a b Bakunin 1991: Mikhail Bakunin wrote in 1873: "These elected representatives, say the Marxists, will be dedicated and learned socialists. The expressions "learned socialist," "scientific socialism," etc., which continuously appear in the speeches and writings of the followers of Lassalle and Marx, prove that the pseudo-People's State will be nothing but a despotic control of the populace by a new and not at all numerous aristocracy of real and pseudo-scientists. The "uneducated" people will be totally relieved of the cares of administration, and will be treated as a regimented herd. A beautiful liberation, indeed!"; Goldman 2003, p. xx: Emma Goldman wrote in 1924 "My critic further charged me with believing that 'had the Russians made the Revolution à la Bakunin instead of à la Marx' the result would have been different and more satisfactory. I plead guilty to the charge. In truth, I not only believe so; I am certain of it."; Avrich 1970, pp. 137–128: Paul Avrich wrote "But if Bakunin foresaw the anarchistic nature of the Russian Revolution, he also foresaw its authoritarian consequences..."; Marshall 1993, p. 477: Peter Marshall writes "The result, anticipated so forcefully by Bakunin, was that the Bolshevik revolution made in the name of Marxism had degenerated into a form of State capitalism which operated in the interests of a new bureaucratic and managerial class."; Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 22–23: Igariwey and Mbah write "As Bakunin foresaw, retention of the state system under socialism would lead to a barrack regime..."

- ^

ISBN 9781608461189. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

The Paris Commune of 1871 [...] involved the working class taking control of their city and driving out the French government. Free at last to pursue their dreams, socialists, communists, anarchists and radical Jacobins threw their energies into a social experiment on a huge scale.

- ^ a b Woodcock 1962, pp. 288–290.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 435.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 334–335.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, pp. 158–59.

- ^ Graham 2005, "Chapter 41: The "Anarchists".

- ^ Pernicone 2016, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Turcato 2019, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d Pengam 1987, pp. 60–82.

- ^ Turcato 2019, p. 239.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 498–499.

- ^ Avrich 1984, p. 190.

- ^ Avrich 1984, p. 193.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 499

- ^ Avrich 1984, p. 209: Avrich is quoting Chicago Tribune, 27 June 1886

- ^ Zimmer 2019, p. 357.

- ^ Foner 1986, p. 42.

- ^ Foner 1986, p. 56.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 9.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 280, 441.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 236.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 264.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 441–442.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 441–443.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 266.

- ^ Graham 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 444.

- ^ Graham 2005, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Skirda 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Zimmer 2019, p. 358.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 375.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 426.

- ^ Schmidt & van der Walt 2009.

- ^ Bantman 2019, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Graham 2019, p. 338.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 315.

- ^ Graham 2019, p. 340.

- ^ a b Anderson 2004.

- ^ Bantman 2019, p. 373.

- ^ Graham 2005, p. 150.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 415.

- ^ Pengam 1987, The Reformulation of Communist Anarchism in the 'International Working Men's Association' (IWMA).

- ^ Bantman 2019, p. 373

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 398.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 404.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 316.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 439.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 470.

- ^ Ivianski 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Billington 1999, p. 417.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 633: Marshall also quotes Kropotkin: "Personally I hate these explosions, but I cannot stand as a judge to condemn those who are driven to despair". Elsewhere he wrote: "Of all parties I now see only one party - the Anarchist - which respects human life, and loudly insists upon the abolition of capital punishment, prison torture and punishment of man by man altogether. All other parties teach every day their utter disrespect of human life."

- Tolstoy

- anarcho-syndicalist Fernand Pelloutierargued in 1895 for renewed anarchist involvement in the labor movement on the basis that anarchism could do very well without "the individual dynamiter"

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 15: Woodcock also mentions Malatesta and other prominent Italian anarchists in p.346

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 633–634.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 634–636.

- ^ Dirlik 1991.

- ^ D'Agostino 2019, p. 423.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, pp. 471–472.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 471.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 472–473.

- ^ a b Avrich 2006, p. 204.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 473.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 475.

- ^ D'Agostino 2019, p. 426.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 476.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 477.

- ^ Nomad 1966, p. 88.

- ^ Skirda 2002, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Skirda 2002, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Skirda 2002, p. 123.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 482.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 450.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 510–511.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 427.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 501.

- ^ Montgomery 1960, p. v.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 467.

- ^ Holborow 2002.

- ^ Pugliese 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Pugliese 2004, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Graham 2005, p. 408.

- ^ Goodway 2013, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Berry 1999, pp. 52–54.

- ^ a b Beevor 2006, p. 46.

- ^ Bolloten 1984, p. 1107.

- ^ a b Birchall 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 473.

- ^ a b Yeoman 2019, pp. 429–430.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 455.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 458.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, p. 430.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, pp. 430–431.

- ^ Bolloten 1984, p. 54.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, pp. 433–435.

- ^ Marshall1993, p. 461.

- ^ Marshall1993, p. 462.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, p. 436.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, pp. 438–439.

- ^ Thomas 2001, p. 458.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 466.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, p. 441.

- ^ Kinna & Prichard 2009, p. 271.

- ^ Kinna & Prichard 2009, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Levy 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Dirlik 2010, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Levy 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 519–523.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 523–525.

- ^ Dirlik 2010, p. 133.

- ^ a b Levy 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 527–528.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 528.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 28–29 & 33.

- ^ Laursen 2019, p. 157.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 504–508.

- ^ Laursen 2019, pp. 157–58.

- ^ Laursen 2019, p. 162.

- ISBN 9781604860641

- ISBN 9780879260064

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 496–497.

- ^ Fiala 2013, Emerson and Thoreau on Anarchy and Civil Disobedience.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 220.

- ^ a b c Marshall 1993, p. 499.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 498.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 222.

- ^ Ryley 2019, p. 232.

- ^ Katz 1976.

- ^ McElroy 2003, pp. 52–56.

- ^ Avrich 2005, p. 212.

- ^ Avrich 2005, p. 230.

- ^ Roslak 1991, p. 381-83.

- ^ Hutton 2004.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 20.

- ^ Goodway 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Conversi 2016, p. 7, Bohémiens, Artists, and Anarchists in Paris.

- ^ Bookchin 1995, 2. Individualist Anarchism and Reaction.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 440.

- Steinlen and Maximilien Luce

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 440–441.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 223.

- ^ Evren & Kinna 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Woodcock 1962, p. 468, epilogue.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 539

- ^ Thomas 1985, p. 4

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 540–542

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 547.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 548

- ^ Berry 2019, p. 449.

- ^ Berry 2019, p. 453.

- ^ Berry 2019, p. 455.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 548.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 546–547: Marshall names Daniel Guerin, Tom Nairn, Jean Maitron

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 546: Peter Marshall makes a pun, commenting on the protestors: "They had failed to uncover the beach under the paving stones of Paris."

- ^ Berry 2019, pp. 457–465.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 551.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 553.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 557.

- ^ Williams 2015, p. 680.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, pp. 164–65.

- ^ Graeber & Grubacic 2004.

- ^ a b Kinna & Prichard 2009, p. 273.

- ^ Dupuis-Déri 2019, pp. 471–472.

- ^ a b Ramnath 2019, p. 691.

- ^ a b Rupert 2006, p. 66.

- ^ Dupuis-Déri 2019, p. 474.

- European Union meeting in Gothenburg (June 2001), the G8 Summit in Genoa (July 2001), the G20 summit in Toronto (2010) and the G20 summit in Hamburg(2017)."

- S2CID 144776094.

- ^ Critchley 2013, p. 125.

- ^ Honeywell 2021.

- ^ Honeywell 2021, pp. 34–44.

- ^ Honeywell 2021, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Honeywell 2021, pp. 1–3.

Sources

Secondary sources (books and journals)

- Adams, Ian (2001). Political Ideology Today. ISBN 978-0-7190-3347-6.

- Anderson, Benedict (July–August 2004). "In the world-shadow of Bismarck and Nobel". New Left Review. II (28).

- S2CID 159947322.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-691-00600-0.

- ISBN 978-0-691-04494-1.

- ISBN 978-1-904859-48-2.

- ISBN 978-1-871082-16-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-36973-2.

- Bantman, Constance (2019). "The Era of Propaganda by the Deed". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- Berry, David (1999). "'Fascism or Revolution!' Anarchism and Antifascism in France, 1933-39". S2CID 145130553.

- Berry, David (2019). "Anarchism and 1968". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Billington, James H. (1999). Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith. ISBN 978-1-4128-1401-0.

- Birchall, Ian (2004). Sartre Against Stalinism. ISBN 978-1-57181-542-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8078-1906-7.

- ISBN 978-1-873176-83-2.

- Carlson, Andrew (1972). "Philosophical Egoism: German Antecedents". ISBN 978-0-8108-0484-5.

- Conversi, Daniele (9 May 2016). "Anarchism, Modernism, and Nationalism: Futurism's French Connections, 1876–1915". S2CID 148353911.

- Cornell, Andrew (2016). ISBN 978-0-520-96184-5.

- ISBN 978-1-78168-017-9.

- Crone, Patricia (2000). "Ninth-Century Muslim Anarchists" (PDF). doi:10.1093/past/167.1.3. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- D'Agostino, Anthony (2019). "Anarchism and Marxism in the Russian Revolution". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- de Acosta, Alejandro (2009). "Two undecidable questions for thinking in which anything goes". In Randall Amster (ed.). Contemporary Anarchist Studies: An Introductory Anthology of Anarchy in the Academy. Luis Fernandez, Abraham DeLeon. ISBN 978-0-415-47402-3.

- ISBN 978-0-520-07297-8.

- ISBN 978-9004188488.

- Dodson, Edward (2002). The Discovery of First Principles: Volume 2. ISBN 978-0-595-24912-1.

- ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Edwards, Stewart (1969). Selected Writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. ISBN 9780598059338.

- Engel, Barbara (2000). Mothers and Daughters. Evanston: ISBN 978-0-8101-1740-2.

- Evren, Süreyyya; Kinna, Ruth (2015). "George Woodcock: The Ghost Writer of Anarchism". Anarchist Studies. 23 (1).

- Fiala, Andrew (2013). "Political Skepticism and Anarchist Themes in the American Tradition". European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy. V-2 (2). .

- Firth, Rhiannon (2019). "Utopianism and Intentional Communities". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Foner, Philip Sheldon (1986). May day: a short history of the international workers' holiday, 1886–1986. New York: ISBN 978-0-7178-0624-9.

- Goldman, Emma (2003). "Preface". ISBN 978-0-486-43270-0.

- ISBN 978-1-60486-221-8.

- ISBN 978-1-135-03756-7.

- Graeber, David; Grubacic, Andrej (2004). "Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century". Znet. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-55164-250-5.

- ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Holborow, Marnie (9 November 2002). "Daring But Divided (Reviews & Culture)". Socialist Worker. No. 268. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Honeywell, C. (2021). Anarchism. Key Concepts in Political Theory. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-5095-2390-0. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Ivianski, Zeev (1988). "Source of Inspiration for Revolutionary Terrorism — The Bakunin — Nechayev Alliance". Journal of Conflict Studies. 8 (3): 49–68.

- ISBN 9780674036413.

- Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (2010). New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-3241-8.

- Hutton, John G. (2004). Neo-Impressionism and the Search for Solid Ground: Art, Science, and Anarchism in Fin-de-siecle France. ISBN 978-0-8071-1823-8.

- ISBN 978-0-380-40550-3.

- Kinna, Ruth; Prichard, Alex (2009). "Anarchism Past, present, and utopia". In Randall Amster (ed.). Contemporary Anarchist Studies: An Introductory Anthology of Anarchy in the Academy. Luis Fernandez, Abraham DeLeon. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47402-3.

- Laursen, Ole Birk (2019). "Anti-Imperialism". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-1-138-78276-1.

- ISBN 978-0-415-87456-4.

- ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1.

- Mbah, Sam; Igariwey, I. E. (1997). African Anarchism: The History of a Movement. ISBN 978-1-884365-05-8.

- ISBN 9780739104736.

- McKinley, C. Alexander (2019). "The French Revolution and 1848". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-18151-4.

- Montgomery, Robert H. (1960). Sacco-Vanzetti: The Murder and the Myth. New York: Devin-Adair.

- Moya, Jose C (2015). "Transference, culture, and critique The Circulation of Anarchist Ideas and Practices". In Geoffroy de Laforcade (ed.). In Defiance of Boundaries: Anarchism in Latin American History. Kirwin R. Shaffer. ISBN 978-0-8130-5138-3.

- ISBN 978-0-900384-89-9.

- Nomad, Max (1966). "The Anarchist Tradition". In Drachkovitch, Milorad M. (ed.). Revolutionary Internationals 1864 1943. ISBN 978-0-8047-0293-5.

- Ossar, Michael (1980). Anarchism in the Dramas of Ernst Toller: The Realm of Necessity and the Realm of Freedom. ISBN 978-0-87395-393-1.

- Pengam, Alain (1987). "Anarchist-Communism". In Rubel Maximilien; Crump John (eds.). Non-Market Socialism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. ISBN 978-0312005245.

- Pernicone, Nunzio (2016). Italian Anarchism, 1864-1892. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-63268-1.

- Pugliese, Stanislao G. (13 January 2004). Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and the Resistance in Italy: 1919 to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-7971-2.

- Ramnath, Maia (2019). "Non-Western Anarchisms and Postcolonialism". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4411-3223-9.

- Roslak, Robyn S. (1991). "The Politics of Aesthetic Harmony: Neo-Impressionism, Science, and Anarchism". JSTOR 3045811.

- ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Rupert, Mark (2006). Globalization and International Political Economy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7425-2943-4.

- Ryley, Constance (2019). "Individualism". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Schofield, Malcolm (July 1999). The Stoic Idea of the City. ISBN 978-0-226-74006-5.

- Sheehan, Seán (2003). Anarchism. ISBN 978-1-86189-169-3.

- ISBN 978-1-902593-19-7.

- Schmidt, Michael; van der Walt, Lucien (2009). "Still fanning the flames: An interview with Michael Schmidt and Lucien van der Walt - Revolution by the Book : The AK Press Blog". revolutionbythebook.akpress.org. Archived from the original on 21 December 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Thomas, Paul (1985). Karl Marx and the Anarchists. London: ISBN 978-0-7102-0685-5.

- Thomas, Hugh (2001). The Spanish Civil War. London: ISBN 978-0-14-101161-5.

- Turcato, Davide (2019). "Anarchist Communism". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

- Wilbur, Shawn P. (2019). "The Spanish Civil War". In S2CID 157359096.

- Williams, Dana M. (2015). "Black Panther Radical Factionalization and the Development of Black Anarchism". S2CID 145663405.

- Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Melbourne: Penguin.

- Yeoman, James Michael (2019). "The Spanish Civil War". In S2CID 157359096.

- Zimmer, Kenyon (2019). "Haymarket and the Rise of Syndicalism". In ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.

Tertiary sources (encyclopedias and dictionaries)

- Fiala, Andrew (3 October 2017). "Anarchism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Forman, Michael (13 April 2009). ISBN 978-1-4051-8464-9.

- Lehning, Arthur (2003). "Anarchism". Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Archived from the original on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- Leopold, David (2015). "Max Stirner". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Miller, Martin A.; Woodcock, George; Dirlik, Arif; Rosemont, Franklin (14 September 2018). "Anarchism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018. The current version of Anarchism in Britanicca

- Miller, David (1991). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-17944-3.

- Philip, Mark (20 May 2006). "William Godwin". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.