Anarchism in Ukraine

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who inhabited the region up until the 18th century. Philosophical anarchism first emerged from the radical movement during the Ukrainian national revival, finding a literary expression in the works of Mykhailo Drahomanov, who was himself inspired by the libertarian socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. The spread of populist ideas by the Narodniks also lay the groundwork for the adoption of anarchism by Ukraine's working classes, gaining notable circulation in the Jewish communities of the Pale of Settlement.

By the outbreak of the

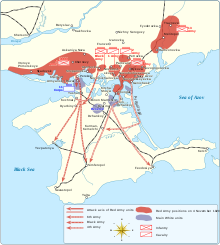

Ukraine became a stronghold of anarchism during the revolutionary period, acting as a counterweight to Ukrainian nationalism, Russian imperialism and Bolshevism. The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine (RIAU), led by Makhno, carved out an anarchist territory in the south-east of the country, centered in the former cossack lands of Zaporizhzhia. By 1921, the Ukrainian anarchist movement was defeated by the Bolsheviks, who established the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in its place.

Anarchism experienced a brief resurgence in Ukraine during the time of the New Economic Policy, but was again defeated following the rise of totalitarianism under the rule of Joseph Stalin. Further expressions of anarchism existed in the breach of Soviet Ukrainian history, before finally reemerging onto the public sphere following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In the 21st century, the Ukrainian anarchist movement has experienced a resurgence, itself coming into conflict with the rising far-right following Euromaidan.

History

At the western-most point of the

By this time, the

Dedicated to the preservation of "Cossack freedoms",

Rising radicalism

Radicalism spread through Ukraine in the wake of the War of 1812, as the rise in calls for abolition of the Tsarist autocracy and serfdom led to the establishment of the Southern Society of the Decembrists in 1821. Ukrainian Decembrists were more radical than their northern counterparts, calling for the overthrow of the monarchy and its replacement with a revolutionary republic.[9] Following the death of Alexander I, the Southern Society in Kyiv staged a revolt against the Russian Empire, but it was suppressed.[10]

Radicalism was raised further during the Ukrainian national revival, as Brotherhoods began to advocate for Ukrainian autonomy and the replacement of the Empire with a pan-Slavic federation organized along liberal democratic lines, with Taras Shevchenko even displaying revolutionary sentiments.[11] The Ukrainian intellectual hromadas, inspired by Russian populism, began to engage with the peasantry - leading to the rise of agrarian socialist tendencies in Ukrainian radical circles.

The most prominent of the hromadas was the one in Kyiv, founded in 1859 by populist students of the

In 1874, the Narodniks' "Going to the People" campaign culminated in a number of Ukrainian revolutionary anarchists (buntars), led by Yakov Stefanovich, organizing a peasant revolt in Chyhyryn, before being suppressed by Russian authorities.[14] Alexander II subsequently issued the Ems Ukaz which banned the use of the Ukrainian language, resulting in the repression of the hromadas and Drahomanov's flight into exile in Geneva,[12] where he established the Geneva Circle, the first Ukrainian socialist organisation. Drahomanov's socialist tendencies brought him into conflict with more moderate members of the Hromada, as well as the "chauvinist" and "dictatorial" Russian revolutionaries, leaving him isolated from many of his contemporaries by 1886.[13] In Galicia, which Drahomanov had placed at the center of the Ukrainian national struggle due to its constitutionalism, Drahomanov's disciple Ivan Franko found himself persecuted by the Austrian authorities and ostracised by local religious conservatives, due to his staunch anti-clericalism.[13]

Nonetheless, in 1890 Franko was able to found the

1905 Revolution

Popular discontent with the

Juda Grossman described the rise of anarchist groups in the wake of the revolution as though they "sprang up like mushrooms after a rain".[23] Jewish anarchist groups sprouted up throughout many of the small towns in the Pale, while in the cities of Ukraine, the anarchist movement that had first appeared in Odesa and Katerynoslav had spread to Kyiv and Kharkiv.[24] In Huliaipole, the Union of Poor Peasants was formed to carry out expropriations against the rich, with a young Nestor Makhno joining the group and later being arrested and imprisoned for killing a police officer.[25] The Black Banner, a terrorist organization inspired by the insurrectionary anarchism of Mikhail Bakunin, grew to include a large membership of Russians, Ukrainians and Jews.[26] In Katerynoslav, Odesa and Sevastopol, the Black banner organized a number of detachments that carried out bombings on buildings, murdered and robbed rich people, and fought with the police in the streets. Even the merchant vessels that docked in Odesa's port became the target of expropriations.[27] At his trial, a member of the Odesa branch of the Black Banner explained their method of "motiveless terror":[28]

We recognize isolated expropriations only to acquire money for our revolutionary deeds. If we get the money, we do not kill the person we are expropriating. But this does not mean that he, the property owner, has bought us off. No! We will find him in the various cafes, restaurants, theaters, balls, concerts, and the like. Death to the bourgeois! Always, wherever he may be, he will be overtaken by an anarchist's bomb or bullet.

Although the terrorists within the Black Banner had been energised by their attacks in Odesa, a dissenting Communard group had also emerged that called for the organization of a mass uprising, rather than individual acts of

Alongside

The

Despite the best efforts of the syndicalists, their extremist counterparts attracted far more attention from the press and the government.

I am an Anarchist-Individualist [...] My ideal is the free development of the individual personality in the broadest sense of the word, and the overthrow of slavery in all its forms. [...] Proudly and bravely we shall mount the scaffold, casting a look of defiance at you. Our death, like a hot flame, will ignite many hearts. We are dying as victors. Forward, then! Our death is our triumph!

Contempt of court was common among anarchist defendants, with one terrorist from Odesa, Lev Aleshker, attacking the judges: "You yourselves should be sitting on the bench of the accused! [...] Down with all of you! Villainous hangmen! Long live anarchy!" In Aleshker's last testament, he predicted the coming of an anarchist future:[46]

Slavery, poverty, weakness, and ignorance—the eternal fetters of man—will be broken. Man will be at the center of nature. The earth and its products will serve everyone dutifully. Weapons will cease to be a measure of strength and gold a measure of wealth; the strong will be those who are bold and daring in the conquest of nature, and riches will be the things that are useful. Such a world is called "Anarchy." It will have no castles, no place for masters and slaves. Life will be open to all. Everyone will take what he needs—this is the anarchist ideal. And when it comes about, men will live wisely and well. The masses must take part in the construction of this paradise on earth.

Five young anarchists were brought to trial for the bombing of the Cafe Libman in Odesa, all of them being sentenced to the death penalty. One of the defendants, Moisei Mets, denied any criminal guilt while also confessing to the bombing, declaring to the court that they demanded nothing less than "the final annihilation of eternal slavery and exploitation". Before his execution, Mets declared: "Death and destruction to the whole bourgeois order! Hail the revolutionary class struggle of the oppressed! Long live anarchism and communism!"[47]

In Odesa alone, 167 anarchists were tried in the wake of the revolution, including 12 anarcho-syndicalists, 94 members of the Black Banner, 51 sympathisers, 5 members of the SR Combat Organization and 5 members of the Anarchist Red Cross. They were mostly young people of mixed Russian, Ukrainian and Jewish backgrounds, of whom 28 received the death penalty and 5 escaped prison.[48] One of those that escaped was Olha Taratuta, who fled to Geneva and joined the buntars before returning to Katerynoslav and joining an anarcho-communist "battle detachment", which saw her arrested again and this time sentenced to hard labor.[49] Vladimir Ushakov had also fled capture in Saint Petersburg, hiding out in Lviv before joining the Katerynoslav battle detachment and going on to expropriate a bank in Yalta. He was caught in the act and taken to prison in Sevastopol, where he committed suicide during a failed escape attempt.[50] The leaders of the anarcho-syndicalist movement in Odesa and the anarcho-communist movement in Kyiv were all sentenced to long terms of hard labor.[51]

The mass imprisonment of anarchist agitators affected each of them differently, with some taking the time to educate themselves and write of their experiences.[52] In the Butyrka prison, Nestor Makhno met Peter Arshinov, who educated the young peasant on the anarcho-communist theories of Bakunin and Kropotkin, up until their release following the February Revolution.[53] Makhno subsequently returned to Ukraine, where he began organizing an agricultural workers' union and was later elected chairman of the Huliaipole Soviet, from which he ordered the armed expropriation of land by the peasantry.[54]

During

Makhnovist Revolution

The outbreak of the

In July, attempts were made to unify the revolutionary anarchist movement, with an anarchist conference in Kharkiv discussing the revolutionary role of factory committees versus trade unions and how they could convert the world war into a world revolution. They also established an "Anarchist Information Bureau" to organize a national conference and gauge the movement's strength throughout the country.[59] It was around this time that the Ukrainian revolutionary anarchist Nestor Makhno returned to his native Huliaipole, where he became involved as a union organizer among the local peasants. By August 1917, Makhno had been elected as the Chairman of the local Soviet, a position from which he organized an armed peasant band to expropriate the large privately held estates and redistribute those lands equally to the whole peasantry.[60]

As the year went on, more anarchist political prisoners were released from prison and returned from exile, which brought a number of intellectuals into the movement.[56] By the turn of 1918, further anarchist conferences had been held in Donbas, Kharkiv and Katerynoslav, resulting in the foundation of the newspaper Golos Anarkhista and the election of a Donbas Anarchist Bureau. The Bureau then organized a series of political lectures in Ukraine, inviting anarchist intellectuals such as Juda Grossman, Nikolai Rogdaev and Peter Arshinov.[61] It was at this time that Volin returned to Ukraine and began work for the People's Commissariat for Education in Kharkiv, even getting so far as to turn down an appointment that would have made him the Ukrainian Commissar for Education.[62]

But following the October Revolution, the anarchist movement came into conflict with the Bolsheviks. The Kharkiv Anarchist-Communist Association described the new soviet state as a "commissarocracy, the ulcer of our time", due to the centralization of power under the Council of People's Commissars, the direction of economics by the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy and the repression of dissident elements by the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission.[63] In Katerynoslav, anarcho-communists called on the masses to overthrow the Bolshevik dictatorship and establish a libertarian socialist society in its place.[64] Left-wing opposition to the Bolsheviks intensified after the ratification of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ceded the entirety of Ukraine to the Central Powers.[65]

Ukrainian anarchists responded with the formation of armed detachments known as the

Fleeing from the repression in Petrograd and Moscow, Russian anarchists sought asylum in the "wild fields" of Ukraine, where the anarchist movement was still strong. By late 1918, the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations had been founded in Kharkiv and established branches in all of Ukraine's major cities.[70] Among the Nabat's most prominent leaders were Volin, Aron Baron and Peter Arshinov,[71] with its youth wing led by Senya Fleshin and Mark Mratchny.[72] At its first conference in Kursk, the Nabat recognized the importance of building a nationwide anarchist federation at all levels of Ukrainian society, encouraging anarchists to participate in non-partisan soviets, factory committees and peasant councils,[73] However, the Nabat's subsequent congress would end up discussing how the trade unions had absorbed the factory committees and how the Bolsheviks had taken over the soviets and transformed them into instruments of the state.[74]

While the Nabat were critical of the Bolshevik dictatorship, it reserved most of its hostility for the White movement,

Following the

The region of

The Makhnovists remained on good terms with the Bolsheviks at this time. When famine threatened Petrograd and Moscow, Huliaipole's Ukrainian peasants exported large amounts of grain to the Russian cities, while Makhno himself was cast as a "courageous partisan" by the Soviet press. By March 1919, the Insurgent Army had even been absorbed into the Red Army, becoming the 7th Ukrainian Soviet Division, subject to the orders of the Revolutionary Military Council.[89] The Ukrainian Front of the Red Army, although commanded by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, was largely made up of Ukrainian peasants led by the atamans Nestor Makhno and Nykyfor Hryhoriv. Considering themselves inheritors of the Zaporozhian Host, the peasantry were less committed to Bolshevism than they were to their liberation from "all those they considered their oppressors".[90]

Hostilities within the Front grew over time, as the Bolshevik leadership developed a distaste for the peasant base and began to reign in the autonomy of the "free soviets".

When Denikin's forces began an offensive against Moscow, the Makhnovists were initially forced into a retreat to

The Makhnovists resolved to defend their territory against both the Red and the White armies, with Trotsky again declaring Makhno an outlaw and the Makhnovists producing propaganda to persuade Red Army soldiers not to take up arms against them.

Following the dissolution of the Ukrainian People's Republic, many Ukrainian nationalist exiles experienced a sharp turn to right-wing politics, with a number even blaming Mykhailo Drahomanov's anarchist ideas for the Ukrainian defeat in the war of independence.[13][a] During the war, antisemitic pogroms had caused the murder of tens of thousands of Jewish people, committed by all sides of the conflict. But it was Symon Petliura that was largely held responsible for the outbreak of violence, due to his position as chairman of the Ukrainian Directorate.[104] While in exile in France, Petliura was assassinated by the Ukrainian Jewish anarchist Sholem Schwarzbard,[105][106] who after a short trial was acquitted on all charges.[107]

Meanwhile, the exiled anarcho-communists began to have their own disagreements in their analysis of the revolution. In order to rectify what he perceived to be a generalized state of disorganization within the anarchist movement,

Resurgence

Following the end of the Povolzhye famine, there was widespread disillusionment with the New Economic Policy (NEP) due to rising levels of unemployment. Furthermore, the death of Lenin, the dissolution of the once-powerful Socialist-Revolutionary Party and the purging of leading academics and civil servants had opened a power vacuum in Ukrainian politics. During this time, there was a noted easing of repressive measures against the anarchist movement, leading to a resurgence of the Ukrainian anarchist movement, as a new generation of youths became attracted to the philosophy.[113]

With the Bolsheviks' attention turned to its ongoing internal conflict between

There was also an upsurge in violent activity, with anarchists being reported to have gassed a theatre pit in

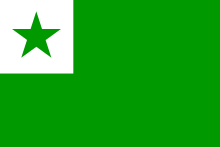

By 1924, there were anarchist groups in at least 28 Ukrainian cities. In the Odesa alone, there were three anarchist workers' circles, a youth group, a published journal and a library, with the police knowing of hundreds of anarchists in the city. Anarchists also organized within independent groups that were disconnected from the anarchist movement, such as Esperanto clubs and masonic bodies, which offered them a clandestine platform for their activities.[121] In Kharkiv, anarchists re-established the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations, organized strike actions, published propaganda and developed contact with anarchists throughout Ukraine and Russia. In April 1924, they were subject to a wave of raids and arrests, but continued their underground organizing work, even planning an All-Union Anarchist Congress before another wave of arrests forced leading Kharkiv anarchists into exile.[122] In Kyiv, anarcho-syndicallists made attempts to unify the Ukrainian anarchist movement, but the arrest waves continued, resulting in the suppression of anarchist youth groups and a dissident construction workers' union, as well as a number of clandestine groups in various other cities of Ukraine.[123] Despite a subsequent arrest wave in 1925, the anarchist movement remained strong in Poltava, where young people continued to adopt anarchism even as more of them were being arrested, imprisoned and exiled.[124]

The growth of anarchist tendencies among Ukrainian students continued, with a number of youth groups sprouting up in cities throughout Ukraine, leading Communist Party officials to officially call for the repression of the youth anarchist movement.

Repression largely resulted in the anarchist movement being pushed further away from legality and into clandestinity, as punitive measures were focused mostly on a few dozen prominent members of the anarchist old guard, with the secret police unable to infiltrate the clandestine "wildcat" groups. Imagined cells of underground anarchists engaged in acts of

Soviet rule

During

After the

Independent Ukraine

The Ukrainian anarchist movement, which had reformed underground in the 1970s and grew substantially during the Revolutions of 1989, finally re-emerged publicly in the newly independent Ukraine.[136] In 1994, the Revolutionary Confederation of Anarcho-Syndicalists (RKAS) was established in Ukraine, gaining 2,000 members by 2000.[136][137] The RKAS coordinated trade unions, formed "Black Guard" defense units and established worker cooperatives around the country.[136]

But the Ukrainian new left that had first constituted itself during the period of

Revolution of Dignity

Upon the outbreak of the Maidan protests, the Ukrainian new left were supportive of the movement, emphasising the promotion of "European values" such as gender equality and minority rights.[b] The Ukrainian new left engaged in the self-organization of the Maidans, coordinating protests, self-defense, education and media engagement, describing the process as a form of "spontaneous anarchism".[143] Direct Action was able to mobilize students in Kyiv to hold popular assemblies, but was not able to institutionalize their control over education policy or even break from the Anti-corruption agenda of the neoliberals. Members of the AWU in Lviv and Kharkiv managed to get increased recognition for their participation in the movement, but were also unable to shift the agenda of the local protests towards left-wing politics.[144]

The disorganized and small groups of the new left quickly found themselves outpaced by far-right groups, which attacked new left activists for their promotion of egalitarian and feminist ideas, resulting in the marginalization of the organized left in the Maidan.[145][146][136] Faced with the dilemma of continued participation in the Maidan movement in the face of an increasingly right-wing agenda, attempts to establish a left-wing "third camp" were stillborn, leaving the Ukrainian new left to slowly become the left-wing of national liberalism in Ukraine.[147] The new left's support for the anti-authoritarianism and spontaneous self-organization of the Maidan also brought it into conflict with the Anti-Maidan movement, which the new left opposed due to its Russian nationalism and cultural conservatism.[148][149]

By the end of the

Russo-Ukrainian War

The escalation of the conflict and the

Following this period of renewed conflict, in 2015 a Ukrainian branch of Revolutionary Action was established, organizing around the principles of solidarity and direct action.[152] The organization has held demonstrations outside the Belarusian embassy,[153][154] organized militant anarchist training camps on the outskirts of Kyiv[155] and have claimed responsibility for attacks on neo-Nazis.[156][157]

On 27 October 2019, insurrectionary anarchists carried out a bomb attack against a mobile communications tower, in the Proletarskyi District in Donetsk. It was reportedly done to draw attention to the torture being performed by the state security forces of the Donetsk People's Republic.[158]

In the wake of the

See also

Notes

- ^ The Ukrainian Radical Party (URP) itself maintained a commitment to both socialism and Ukrainian independence, in opposition to the right-wing nationalists and the Bolsheviks respectively. It became a member of the Labour and Socialist International and continued electoral activities in the new Republic of Poland, gaining 20,000 members by 1934.[15]

- Timothy D. Snyder argued that the Revolution of Dignity initially had a left-wing and anti-authoritarian character, citing the grassroots self-organization of a gift economy in the Maidans, where crowdfunding was used to coordinate mutual aid.[142]

References

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Skirda 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 44–49.

- OCLC 51610936. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ OCLC 918591356. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ OCLC 724265856. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 198–201.

- ^ OCLC 499306441.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 12.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 42.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 43.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 209; Skirda 2004, pp. 20–29.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 44.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 48.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 57.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 60.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 56.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 62.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 78.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 102–105.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 67.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 68.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 69.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 70.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 209; Skirda 2004, pp. 29–33.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 209–210; Skirda 2004, pp. 34–41.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 123–125.

- ^ a b Avrich 1971, p. 125.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 173.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 199.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 181.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 186.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 187.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 188.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 204.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 206.

- ^ a b Avrich 1971, p. 207.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 209.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 210; Skirda 2004, pp. 44–48.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 210–211; Skirda 2004, pp. 48–52.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 211–212; Skirda 2004, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 212–213; Skirda 2004, pp. 55–67.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 213; Skirda 2004, p. 67.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 67.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 213; Skirda 2004, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 213.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 214.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 215.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 216.

- ^ a b Magocsi 1996, p. 499.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 217.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 218.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 219.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 220.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 221.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, p. 502.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 173–186.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, pp. 506–507.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 275.

- OCLC 1117624045. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- OCLC 1311479. Archived from the originalon 13 September 2012.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 241.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 241-242.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 243.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 247.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 174.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 175.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 176.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b Savchenko 2017, p. 181.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 177.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 178.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 179.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 180.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 182.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 183.

- ^ Savchenko 2017, p. 184.

- ^ "The famine of 1932–33". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33 – a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians ... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine ... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated ... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself.

- ^ Damier, Vadim (November 1998). "Fate of the Makhnovist". Прямое действие. Translated by Riltok. Confederation of Revolutionary Anarcho-Syndicalists. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, pp. 701.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, pp. 702–703.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, pp. 709.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, pp. 717–724.

- ^ a b c d e Schmidt, Michael (5 December 2014). "The neo-Makhnovist revolutionary project in Ukraine". Anarkismo.net. Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- OCLC 839317311.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, pp. 823–824.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, p. 825.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, p. 824.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, pp. 824–825.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, p. 822.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, p. 826.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, pp. 826–827.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, pp. 825–826.

- ^ Autonomous Workers’ Union; CrimethInc. (12 March 2014). "Ukraine: How Nationalists Took the Lead". CrimethInc. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, p. 827.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, pp. 827–828.

- ^ Rautiainen, Antti (7 May 2014). "Anarchism in the context of civil war". Autonomous Action. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, pp. 830–831.

- ^ Ishchenko 2020, p. 831.

- ^ Ilyash, Igor; Andreeva, Ekaterina (17 March 2017). "Колер пратэсту – чорны. Анархісты гатовыя даць сілавы адпор". Belsat.eu (in Belarusian). Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "Анархисты в Киеве пикетировали белорусское посольство". Charter 97. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "Анархисты в Киеве повесили на ограждение посольства Беларуси чучело Лукашенко". Nasha Niva (in Russian). 25 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "Anarchistic camp near Kiev". Revolutionary Action. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Hanrahan, Jake (10 April 2019). "Ukraine's Anarchist Underground". Popular Front. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Attack on nazis from C14 in Kiyv". Revolutionary Action. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Anarchist bomb attack in Donetsk". Anarchy Today. 30 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Ludwig, Mike (5 March 2022). "War Is Forcing Ukrainian Leftists to Make Difficult Decisions About Violence". Truthout. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "EVERYTHING FOR THE FRONT, EVERYTHING FOR WINNING!". Кампанія Солідарності з Україною. 17 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Koshiw, Isobel (26 May 2022). "'Putin's terror affects everyone': anarchists join Ukraine's war effort". The Guardian. Kyiv. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

Bibliography

- OCLC 579425248.

- OCLC 1154930946.

- Darch, Colin (2020). Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21. OCLC 1225942343.

- Dubovik, Anatoly; Rublyov, D.I. (2009). After Makhno: The Anarchist underground in the Ukraine in the 1920s and 1930s. Translated by Szarapow. OCLC 649796183.

- OCLC 792898216.

- Ishchenko, Volodymyr (2020). "Left divergence, right convergence: anarchists, Marxists, and nationalist polarization in the Ukrainian conflict, 2013–2014". S2CID 212781355.

- OCLC 757049758.

- OCLC 690866794.

- OCLC 187835001.

- OCLC 924883878.

- Mitchell, Ryan Robert (2009). "Anarchism, Ukraine". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. pp. 1–4. OCLC 8681978718.

- Palij, Michael (1976). The Anarchism of Nestor Makhno, 1918–1921. Publications on Russia and Eastern Europe of the Institute for Comparative and Foreign Area Studies. Vol. 7. OCLC 2372742.

- OCLC 470314979.

- OCLC 7180822604. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Shubin, Aleksandr (2010). "The Makhnovist Movement and the National Question in the Ukraine, 1917–1921". In Hirsch, Steven J.; OCLC 868808983.

- OCLC 58872511.

- OCLC 890439998.