List of giant squid specimens and sightings

This list of giant squid specimens and sightings is a comprehensive timeline of recorded human encounters with members of the genus Architeuthis, popularly known as giant squid. It includes animals that were caught by fishermen, found washed ashore, recovered (in whole or in part) from sperm whales and other predatory species, as well as those reliably sighted at sea. The list also covers specimens incorrectly assigned to the genus Architeuthis in original descriptions or later publications.

Background

History of discovery

Tales of giant squid have been common among mariners since ancient times, but the animals were long considered

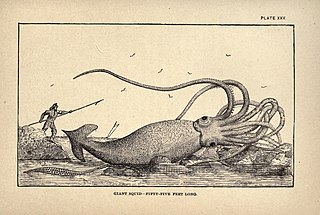

The giant squid's existence was established beyond doubt only in the 1870s, with the appearance of an extraordinary number of complete specimens—both dead and alive—in Newfoundland waters (beginning with #21).[22] These were meticulously documented in a series of papers by Yale zoologist Addison Emery Verrill.[23][nb 3] Two of these Newfoundland specimens, both from 1873, were particularly significant as they were among the earliest to be photographed: first a single severed tentacle—hacked off a live animal as it "attacked" a fishing boat (#29)[24]—and weeks later an intact animal in two parts (#30).[nb 4] The head and limbs of this latter specimen were famously shown draped over the sponge bath of Moses Harvey, a local clergyman, essayist, and amateur naturalist.[29] Harvey secured and reported widely on both of these important specimens—as well as numerous others (most notably the Catalina specimen of 1877; #42)—and it was largely through his efforts that giant squid became known to North American and British zoologists.[30][nb 5] Recognition of Architeuthis as a real animal led to the reappraisal of earlier reports of gigantic tentacled sea creatures, with some of these subsequently being accepted as records of giant squid, the earliest stretching back to at least the 17th century.[32]

"I confess that until I saw and measured this enormous limb, I doubted the accuracy of some early observations which this specimen alone would suffice to prove worthy of confidence. The existence of gigantic cephalopods is no longer an open question. I, now, more than ever, appreciate the value of the adage: 'Truth is stranger than fiction.'"

—

For a time in the late 19th century, almost every major specimen of which material was saved was described as a new species.[34] In all, some twenty species names were coined.[35] However, there is no widely agreed basis for distinguishing between the named species, and both morphological and genetic data point to the existence of a single, globally distributed species, which according to the principle of priority must be known by the earliest available name: Architeuthis dux.[36]

It is not known why giant squid become stranded on shore, but it may be because the distribution of deep, cold water where they live is temporarily altered. Marine biologist and Architeuthis specialist

Though the total number of recorded giant squid specimens now runs

Distribution patterns

The genus Architeuthis has a

The vast majority of specimens are of oceanic origin, including

Total number of specimens

According to Guerra et al. (2006), 592 confirmed giant squid specimens were known as of the end of 2004. Of these, 306 came from the Atlantic Ocean, 264 from the Pacific Ocean, 20 from the Indian Ocean, and 2 from the Mediterranean Sea. The figures for specimens collected in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans further broke down as follows: 148 in the northeastern Atlantic, 126 in the northwestern Atlantic, 26 in the southeastern Atlantic, 6 in the southwestern Atlantic, 43 in the northeastern Pacific, 28 in the northwestern Pacific, 10 in the southeastern Pacific, and 183 in the southwestern Pacific.[59]

| Region | Number of specimens | % of total | Found stranded or floating (%) | From fishing (%) | From predators (%) | Method of capture unknown (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE Atlantic | 152 | 22.5 | 49 | 31 | 15 | 5 |

| NW Atlantic | 148 | 21.9 | 61 | 30 | 1 | 8 |

| SE Atlantic | 60* | 8.9 | 10 | 60 | 17 | 13 |

| SW Atlantic | 6 | 0.9 | 50 | 16 | 1 | 33 |

| NE Pacific | 43 | 6.4 | 7 | 56 | 30 | 7 |

| NW Pacific | 30* | 4.4 | 30 | 35 | 30 | 5 |

| SE Pacific | 10 | 1.5 | 90 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| SW Pacific | 183 | 27.0 | 12 | 41 | 42 | 5 |

| Indian Ocean | 33** | 4.8 | 6 | 94 | 0 | 0 |

| W Mediterranean | 3 | 0.4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Equatorial/tropical | 9 | 1.3 | 11 | 44 | 45 | 0 |

| All regions | 677 | 100.0 |

- * Underestimates according to Guerra et al. (2011)

- ** Includes records from Durban, South Africa

Procurement, preservation, and display

Preserved giant squid specimens are much sought after for both study and display.

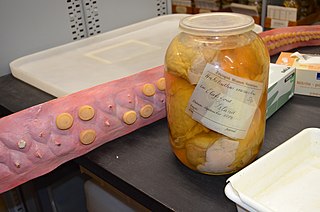

A number of fragmentary giant squid remains were displayed as part of "In Search of Giant Squid", a Smithsonian travelling exhibition curated by Clyde Roper that visited a dozen US museums and other educational institutions between September 2004 and August 2009.[71] The exhibition opened its national tour at Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History, which has maintained a strong association with the giant squid from the time of the Newfoundland strandings in the 1870s. Preparations for the Peabody exhibition, overseen by site curator Eric Lazo-Wasem, uncovered giant squid material in the museum's collections that was not previously known to be extant, including original specimens from Addison Emery Verrill's time.[72]

"Architeuthis is an elusive creature. Its occasional appearance on various beaches around the world has provided hardly more than a glimpse of its majestic and intimidating appearance, and hauling it out of the water in a trawl does it no justice either. Papier-mâché or fiberglass models have given us a sense of its size and shape, but they have not captured its mystery and vitality. The spirit of Architeuthis may well be uncapturable; at least no museum has even come close to this fabulous creature—the only living animal for which the term sea monster is truly applicable."

—Richard Ellis, from the closing remarks of his 1997 article "The models of Architeuthis"[73]

In the late 19th century, the giant squid's popular appeal and desirability to museums—but scarcity of preserved specimens—spawned a long tradition of "life-sized" models that continues to the present day.

Real giant squid specimens have traditionally been preserved in either solutions of

Reported sizes

Giant squid size—long a subject of both popular debate and academic inquiry

Based on a 40-year data set of more than 50

O'Shea & Bolstad (2008) give a maximum mantle length (ML) of 225 cm (7.38 ft) based on the examination of more than 130 specimens, as well as beaks recovered from sperm whales (which do not exceed the size of those found in the largest complete specimens), though there are recent scientific records of specimens that slightly exceed this size (such as #371, a 240 cm (7.9 ft) ML female captured off Tasmania, Australia; see also #647, with an estimated 2.15–3.06 m ML). Remeslo (2011) and Yukhov (2014:248) give a maximum mantle length of 260 cm (8.5 ft) for females from southern waters. Questionable records of up to 500 cm (16 ft) ML can be found in older literature.[96] Paxton (2016a) accepts a maximum recorded ML of 279 cm (9.15 ft), based on the Lyall Bay specimen (#47) reported by Kirk (1880:312), but this record has been called into question as the gladius of this specimen (which should approximate the mantle length) was said to be only 190 cm (6.2 ft) long.[94]

Including the head and arms but excluding the tentacles (standard length), the species very rarely exceeds 5 m (16 ft) according to O'Shea & Bolstad (2008). Paxton (2016a) considers 9.45 m (31.0 ft) to be the greatest reliably measured SL, based on a specimen (#46) reported by Verrill (1880a:192), and considers specimens of 10 m (33 ft) SL or more to be "very probable", but these conclusions have been criticised by giant squid experts.[94]

The giant squid and the distantly related

Species identifications

"Undoubtedly several imperfectly distinguished forms have been included in the earlier anecdotal records of Architeuthis. Moreover, specimens of Architeuthis (the Giant Squid par excellence), the smaller

Ommatostrepheshave been indiscriminately described as 'Giant Squids.'"

—Guy Coburn Robson, from his description of Architeuthis clarkei, a species he erected in 1933 based on a carcass (#107) that washed ashore in Scarborough, England, earlier that year[99]

The taxonomy of the giant squid genus

The literature on giant squid has been further muddied by the frequent misattribution of various squid specimens to the genus Architeuthis, often based solely on their large size. In the academic literature alone, such misidentifications encompass at least the

List of giant squid

Sourcing and progenitors

The present list generally follows "

Earlier efforts to compile a list of all known giant squid encounters throughout history include those of marine writer and artist Richard Ellis.[109] Ellis's first list, published as an appendix to his 1994 work Monsters of the Sea, was probably the first such compilation to appear in print and was described in the book's table of contents as "the most complete and accurate list of the historical sightings and strandings of Architeuthis ever attempted".[110] Ellis's much-expanded second list, an appendix to his 1998 book The Search for the Giant Squid, comprised 166 entries spanning four and a half centuries, from 1545 to 1996.[111] Records which appear in Ellis's 1998 list but are not found in Sweeney & Roper's 2001 list have a citation to Ellis (1998a)—in the page range 257–265—in the 'Additional references' column of the main table.[nb 12]

In addition to these global specimen lists, a number of regional compilations have been published, including

Scope and inclusion criteria

The list includes records of giant squid (genus

Purported sightings of giant squid lacking both

The earliest surviving records of very large squid date to

All developmental stages from hatchling to mature adult are included. In the literature there is a single anecdotal account of a giant squid "egg case",

Specimens misassigned to the genus Architeuthis in print publications or news reports are included, but are clearly highlighted as misidentifications.

List of specimens

Records are listed chronologically in ascending order and numbered accordingly. This numbering is not meant to be definitive but rather to provide a convenient means of referring to individual records. Specimens incorrectly assigned to the genus Architeuthis are counted separately, their numbers enclosed in square brackets, and are highlighted in pink ( ). Records that cover multiple whole specimens, or remains necessarily originating from multiple individuals (e.g. two lower beaks), have the '

- Date – Date on which the specimen was first captured, found, or observed. Where this is unknown, the date on which the specimen was first reported is listed instead and noted as such. All times are local.

- Location – Area where the specimen was encountered, including coordinates and depth information where available. Given as it appears in the cited reference(s), except where additional information is provided in square brackets. The quadrant of a major ocean in which the specimen was found is given in curly brackets (e.g. {NEA}; see Oceanic sectors).

- Nature of encounter – Circumstances in which the specimen was recovered or observed. Given as they appear in the cited reference(s), although "washed ashore" encompasses all stranded animals.

- Identification – Species- or vernacular namehas been applied to the specimen (e.g. "giant squid" or a non-English equivalent), this is given instead.

- Material cited – Original specimen material that was recovered or observed. "Entire" encompasses all more-or-less complete specimens. Names of anatomical features are retained from original sources (e.g. "jaws" may be given instead of the preferred "beak", or "body" instead of "mantle"). The specimen's state of preservation is also given, where known, and any missing parts enumerated (the tentacles, arm tips, reddish skin and eyes are the parts most often missing in stranded specimens, owing to their delicate nature and/or preferential targeting by scavengers).

- Material saved – Material that was kept after examination and not discarded (if any). Information may be derived from outdated sources; material may no longer be extant even if stated as such.

- Sex – Sex and sexual maturity of the specimen.

- Size and measurements – Data relating to measurements and counts. Abbreviations used are based on standardised acronyms in arithmetic precision and original units preserved (metric conversions are shown alongside imperial measurements), though some of the more extreme lengths and weights found in older literature have since been discredited.

- Repository – Institution in which the specimen material is deposited (based on cited sources; may not be current), including boldface. If an author has given a specimen a unique identifying number (e.g. Verrill specimen No. 28), this is included as well, whether or not the specimen is extant.

- Main references – The most important sources, typically ones that provide extensive data and/or analysis on a particular specimen (often primary sources). Presented in author–date parenthetical referencing style, with page numbers included where applicable (those in square brackets refer either to unpaginated works or English translations of originally non-English works; see Full citations). Only the first page of relevant coverage is given, except where this is discontinuous. Any relevant figures ("figs.") and plates ("pls.") are enumerated.

- Additional references – References of lesser importance or primacy, either because they provide less substantive information on a given record (often secondary sources), or else because they are not easily obtainable or possibly even extant (e.g. old newspaper articles, personal correspondence, and television broadcasts) but nonetheless mentioned in more readily accessible published works (see Full citations).

- Notes – Miscellaneous information, often including persons and vessels involved in the specimen's recovery and subsequent handling, and any dissections, preservation work or scientific analyses carried out on the specimen. Where animals have been recorded while alive this is also noted. Material not referable to the genus Architeuthis, as well as specimens on public display, are both highlighted in bold (as "Non-architeuthid" and "On public display", respectively), though the latter information may no longer be current.

The total number of giant squid records listed across this page and successive lists is 714, though the number of individual animals covered is greater (the additional number exceeding 250) as some records encompass multiple specimens (indicated in grey). Additionally, 13 records relate to specimens misidentified as giant squid (indicated in pink).

| # | Date | Location | Nature of encounter | Identification | Material cited | Material saved | Sex | Size and measurements | Repository | Main references | Additional references | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (📷) |

c. 1546[nb 15] | Øresund, near Malmö, Denmark–Norway [since 1658 Malmö has been part of Sweden] {NEA} |

Found washed ashore; "caught live"[175] | "sea monk"; Architeuthis monachus Steenstrup in Harting, 1860; Jenny Haniver made from a skate;[176] Squatina squatina (angelshark)[177] | Entire? | Undetermined | ?WL: ≈3 m | Hamer (1546:[1], fig.); Belon (1553:38, fig.); Rondelet (1554:492, fig.); Belon (1555:32, fig.); Lycosthenes (1557:609, fig.); Gessner (1558:519, fig.); Rondelet (1558:361, fig.); Sluperius (1572:"89", 105, fig.); Vedel (1575); Huitfeldt ([1595]:1545); Gessner (1604:438, fig.); Stephanius ([c. 1650]:344); Steenstrup (1855a:63, 3 figs.); Roeleveld & Knudsen (1980:293, 3 figs.); Ellis (1998a:60, fig.); Paxton & Holland (2005:39, fig. 1) | records of Björn Jónsson á Skarðsá;[nb 16] Scheuchzer (1716:153); Holberg (1733:379); Lönnberg (1891:36); Nordgård (1928:71); Tambs-Lyche (1946:288); Carrington (1957:58, fig.); Muus (1959:170); Russell & Russell (1975:94); Strauss (1975:393, fig.); Aldrich (1980:55); Roeleveld (N.d.) | Contemporaneously regarded as a " sea bishop has also been interpreted as a giant squid carcass[180] or else a Jenny Haniver made from a skate.[181]

| ||

| 2 | autumn 1639 | {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis sp. | Entire | One arm | BL+HL: ≈6 ft (1.8 m); AL: ≈3 ft (0.91 m); TL: ≈16–18 ft (4.9–5.5 m); BC: ≈3–4 ft (0.91–1.22 m) | Thingøre monastery; "museum at Copenhagen" (ZMUC?)[183] | Jónsson ([c. 1645]:238); Ólafsson (1772:716); Steenstrup (1849:950/[9]); Steenstrup (1898:425/[272]); Ellis (1998a:65) | Packard (1873:87); Verrill (1875b:84); Robson (1933:691); Muus (1959:170); Berger (2009:260) | Original Icelandic account is from the contemporaneous Annálar Björns á Skarðsá and has been translated into English.[nb 17] Crude drawing of animal mentioned by Eggert Ólafsson was lost with most of his books when his boat capsized off Iceland in 1768, leading to his death.[185] Identified by Japetus Steenstrup as decapod cephalopod in 1849. | |

| 3 (📷) |

c. 15 October 1673 | Dingle-I-cosh, Kerry, Ireland {NEA} |

Found floating at surface, in process of washing ashore, alive | Dinoteuthis proboscideus More, 1875; Architeuthis monachus;[186] Ommastrephes (Architeuthis) monachus[187] | Entire | Two arms, buccal mass, and suckers taken to Dublin | TL: ≈11 ft (3.4 m) + 9 ft (2.7 m); AL: ≈6–8 ft (1.8–2.4 m); "liver": 30 lb (14 kg) | Undetermined [NMI?]; holotype of Dinoteuthis proboscideus More, 1875 | [Anon.] (c. 1673); Hooke et al. (c. 1674:[1], fig.); More (1875a:4526); Verrill (1875c:214); Tryon (1879b:185); Ellis (1998a:66); Sueur-Hermel (2017:64) | More (1875b:4571); Massy (1909:30); Ritchie (1918:137); Robson (1933:692); Rees (1950:40); Hardy (1956:285); Collins (1998:489) | Found by James Steward. Original material relating to this specimen consists of: a broadsheet printed in | |

| 4 | 1680 | Ulvangen Fjord, Alstadhoug parish, Norway {NEA} |

Not stated | Entire? | Pontoppidan (1753:344) | Steenstrup (1857:184/[18]); Grieg (1933:19) | ||||||

| 5 | 1770 | Jutland, Denmark {NEA} |

Unknown | Muss (1959) | Ellis (1998a:257) | |||||||

| 6 | 27 May 1785 | Grand Banks, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found floating at surface, dead | Architeuthis sp. | BL: 7 ft (2.1 m) | Cartwright (1792:44); Thomas ([1795]:183); Aldrich (1991:457) | Found during George Cartwright's sixth and final voyage to Newfoundland and Labrador. Spotted at 10 am surrounded by birds. Head broke off during retrieval. Described as "a large squid [...] when gutted, the body filled a pork barrel, and the whole of it would have filled a tierce". | |||||

| 7 | November or December 1790 | Arnarnaesvik, Modruvalle, Iceland {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Entire | None; used for cod bait | "longest tentacula": >3 fathoms (5.5 m); "body right from the head": 3.5 fathoms (6.4 m); "so thick that a fullgrown man could hardly embrace it with his arms" | Steenstrup (1849:952/[11]); Steenstrup (1898:429/[276]); Ellis (1998a:68) | February 1792 diary of Sveinn Pálsson (in library of Icelandic Literary Society, in Copenhagen); Verrill (1875b:84); Robson (1933:691) | Called Kolkrabbe ('coal-crab') by local people. Identified by Japetus Steenstrup as decapod cephalopod in 1849. | |||

| 8 | 1700s (reported 1795) | Freshwater Bay, near mouth of St. John's harbour, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Unknown | Architeuthis sp. | Thomas ([1795]:183); Aldrich (1991:457) | |||||||

| 9 | 1700s | Grand Banks, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Unknown | Architeuthis sp. | Aldrich (1991:457) | |||||||

| 10 | 1798 | north coast of Denmark {NEA} |

Not stated | "gigantic squid" | Unknown | "museum at Copenhagen" (ZMUC?) | Packard (1873:87) | Ellis (1998a:257) | ||||

| 11 | 9 January 1802 | off Tasmania, Australia {SWP} |

Found at surface, alive | ?Loligo ["vraisemblablement du genre Calmar [Loligo, Lamarck]"] | "size of a barrel" ["grosseur d'un tonneau"]; AL: 1.9–2.2 m; AD: 18–21 cm | Péron (1807:216) | Quoy & Gaimard (1824:411); Ellis (1998a:257) | Péron (1807:216) wrote: "it rolled with noise in the midst of the waves, and its long arms, stretched out on their surface, stirred like so many enormous reptiles" (translated from the French). | ||||

| 12 | between 1817 and 1820 | Atlantic Ocean, near equator {?} |

Found floating at surface | "énorme calmar" | Partial remains; "tentacles" ("tentacules") missing | WT: 100 " livres " [estimate]; WT: 200 "livres" [estimate; if complete] |

Quoy & Gaimard (1824:411) | Packard (1873:88); Ellis (1998a:257) | Found at surface in calm weather. Quoy & Gaimard (1824:411) opined: "it is easy to imagine that one of these terrible molluscs could readily remove a man from a fairly large boat, but not a medium-tonnage vessel, still less tilting this vessel and endangering it, as some would like to believe" (translated from the French). | |||

| 13 (📷) |

December 1853 | {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis monachus | Entire | Jaws only; radula discarded after poor preservation; jaws cut out; portion used for bait; remainder buried after 2 days | WT: 80–85 kg; jaw measurements Steenstrup (1898:423/[270]) | ZMUC catalog no. CEP-133; holotype of Architeuthis monachus Steenstrup, 1857[192] | Steenstrup (1855b:[14]); Harting (1860:11); Steenstrup (1898:415/[258], pl. 1 figs. 1–2); Kristensen & Knudsen (1983:222) | Steenstrup (1857:[18]); Packard (1873:87); Gervais (1875:91); Verrill (1875b:84); Verrill (1880a:238, pl. 25 fig. 3); Verrill (1882c:51, pl. 12 fig. 3); Posselt (1890:144); Nordgård (1928:71) | "Architeuthis monachus" Steenstrup = nomen nudum[193] | |

| 14 (📷) |

5 November 1855 | western Atlantic Ocean, near Bahamas (31°N 76°W / 31°N 76°W) {NWA} |

Not stated; presumably found floating at surface | Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857; Architeuthis titan[194] | Various parts | Gladius, mouthparts, part of arm, several suckers, and what may be hectocotylus[195] | Male | WL: 377 cm; AL: 1/2 whole length;[196] beak measurements; GL: 6 ft (1.8 m)[197] | ZMUC catalog no. CEP-97 (or CEP-000097) and NHMD-77320 (multiple parts, each in its own glass vessel: gladius, mouthparts, part of arm, several suckers, and what may be hectocotylus); Bergen Museum[198] |

Steenstrup (1857:[18]); Steenstrup (1882:[160]); Steenstrup (1898:413, 450/[260, 298], pls. 3–4); Tryon (1879b:186, pl. 86 fig. 388); Kristensen & Knudsen (1983:222); Glaubrecht & Salcedo-Vargas (2000:273); [NHMD] (2019) | Packard (1873:87); Verrill (1875b:84); Posselt (1890:144); Toll & Hess (1981:753) | Obtained by Capt. Vilhelm Hygom. Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, which was incorporated into collection in 1883 according to catalogue entry. Preserved in 70% ethanol.[195]

|

| 15 | December 1855 | Aalbaekbugten, Denmark {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis sp. | Entire? | Undetermined | None | Muus (1959:170) | Posselt (1890:144) | |||

| 16 (📷) |

Unknown (reported 1860) | Unknown {?} |

Not stated | Architeuthis dux;[199] ?Ommastrephes hartingii;[200] Architeuthis hartingii (Verrill, 1875);[201] nomen nudum[202] | Jaws, buccal mass, detached arm suckers | Jaws, buccal mass, detached arm suckers | ASD: 1.05 in (2.7 cm) | Utrecht University Natural History Museum; holotype of Loligo hartingii Verrill, 1875. Harting specimen No. 1 | Harting (1860:2, pl. 1); Kent (1874d:491); Verrill (1875b:85, fig. 28); Tryon (1879b:149, 184, pl. 60 figs. 194–195); Verrill (1880a:240, pl. 16 fig. 8, pl. 25 fig. 1); Verrill (1882c:52, pl. 12 figs. 1–1c); Pfeffer (1912:37) | Dell (1970:27) | ||

| 17 | 1860 or 1861 | between Hillswick and Scalloway, Shetland, Scotland {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis monachus Steenstrup, 1857; Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857[203] | Undetermined | TL: 16 ft (4.9 m); AL: ≈8 ft (2.4 m); BL: ≈7 ft (2.1 m) | Jeffreys (1869:124); Stephen (1944:263) | More (1875b:4571); Pfeffer (1912:26); Rees (1950:40); Collins (1998:489) | ||||

| 18 (📷) |

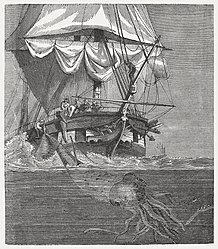

30 November ?1861 [=1860 Rees & Maul] | about 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Teneriffe, Canary Islands {NEA} |

Found floating at surface | Loligo bouyeri;[204] ?Ommastrephes bouyeri[200] | Entire, decomposed | None | BL: 15–18 ft (4.6–5.5 m) | None | Bouyer (1861:1263); Crosse & Fischer (1862:135); Bouyer (1866:275, fig.); Kent (1874a:180); Verrill (1875b:86); Tryon (1879b:149, 184, pl. 59); Bourée (1912:113, fig. 108); Aldrich (1978:2); Ellis (1998a:5, 78); Heuvelmans (2003:185, figs. 95–96, 100) | Frédol (1865:314, pl. 13); Figuier (1866:464, fig. 362); Frédol (1866:362); Mangin (1868:321); Meunier (1871:245); Kent (1874d:491); Gervais (1875:93); Lee (1883:38, fig. 8); Rees & Maul (1956:266); Carrington (1957:53, pl. 3b); Muntz (1995:19, fig. 11); Lagrange (2009:19) | Observed only by officers of the French gunboat . | |

| 19 | 1862 | North Atlantic {NEA/NWA} |

Unknown | Crosse & Fischer (1862) | Ellis (1998a:258) | |||||||

| [1] (📷) |

Unknown; 1870? | Cape Sable, Nova Scotia, Canada {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis megaptera Verrill, 1878 [=Sthenoteuthis pteropus (Steenstrup, 1855)][205] | Entire | Entire | BL: 14 in (36 cm); BL+HL: 19 in (48 cm); EL: 43 in (110 cm); TL: 22–24 in (56–61 cm); AL: 6.5–8.5 in (17–22 cm); FW: 13.5 in (34 cm); FL: 6 in (15 cm); extensive additional measurements | NSMC catalog no. 1870-Z-2; YPM catalog nos. IZ 017932 Archived 3 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine (sucker) & IZ 017713; holotype of Architeuthis megaptera Verrill, 1878;[206] Verrill specimen No. 21 ("Cape Sable specimen") | Verrill (1878:207); Tryon (1879b:187); Verrill (1880a:193, pl. 21); Verrill (1882c:17, pl. 16 figs. 1–9) | Non-architeuthid. Collected by J.M. Jones. | ||

| 20 | September 1870 | Waimarama, east coast of Wellington, New Zealand {SWP} |

Found washed ashore | Entire | Beak | BL+HL: 10 ft 5 in (3.18 m); BC: 6 ft (1.8 m); AL: 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) | In Kirk's possession; Kirk specimen No. 1 | Kirk (1880:310); Verrill (1881b:398) | Meinertzhagen letter 27 June 1879 to Kirk; Pfeffer (1912:32); Dell (1952:98) | Mr. Meinertzhagen sent beak, saved by third party (unidentified), to Kirk. Natives called specimen a "taniwha". | ||

| 21 | 1870 (winter) | Lamaline, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis monachus of Steenstrup | Two specimens; entire? | None?; used as fish bait[207] | Two; EL: 40 ft (12 m) and EL: 47 ft (14 m) | None?; Verrill specimen Nos. 8 & 9 ("Lamaline specimens") | Murray (1874a:162); Verrill (1875a:36); Verrill (1880a:187); Verrill (1882c:11) | Boston Traveller, November 1873; Harvey (1874a:69); Kent (1874a:182); Frost (1934:101); Earle (1977:52) |

Data from Mr. Harvey letter citing Rev. M. Gabriel's statement to Harvey. | |

| 22 (📷) |

October 1871 | Grand Banks, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found floating at surface | Architeuthis princeps Verrill, 1875 | Entire; part used as bait | Jaws obtained from Baird for examination by Verrill | BL: ≈15 ft (4.6 m); BD: 19 in (48 cm); AL: ≈10 ft (3.0 m) [mutilated]; AD: 7 in (18 cm); AC: 22 in (56 cm); beak; BC: 4 ft 8 in (1.42 m); WT: 2,000 lb (910 kg) | Jaws at NMNH[208] (no longer extant?[209]); lower jaw is syntype of Architeuthis princeps Verrill, 1875b; Verrill specimen No. 1 ("Grand Banks specimen" [1st]) | Packard (1873:91); Verrill (1874a:158); Verrill (1874b:167); Verrill (1875b:79, fig. 27); Verrill (1880a:181, 210, pl. 18 fig. 3); Verrill (1882c:5, pl. 11 figs. 3–3a) | Pfeffer (1912:20); Frost (1934:100) | Taken by Capt. Campbell, Schooner B.D. Haskins. | |

| 23 | 1871 | Wellington, New Zealand {SWP} |

?EL: 16 ft (4.9 m) | Dell (1952) | Ellis (1998a:258) | |||||||

| 24 | 1872 (autumn or winter) | Coomb's Cove, Fortune Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found alive in shallow water, having been driven ashore in heavy sea | Entire; "one long arm missing" (later changed to both present) | BL: 10 ft (3.0 m); BD: 3–4 ft (0.91–1.22 m); TL: 42 ft (13 m); AL: ≈6 ft (1.8 m); AD: 9 in (23 cm); skin + flesh: 2.25 in (5.7 cm) thick; EL: 52 ft (16 m) | Unknown; Verrill specimen No. 3 ("Coombs' Cove specimen") | Verrill (1874a:159); Verrill (1874b:167); Verrill (1875a:35); Verrill (1880a:183); Verrill (1882c:7) | Owen (1881:163); Frost (1934:101) | Specimen had a reddish colour. Verrill's data taken from newspaper accounts and 15/VI/1873 T.R. Bennett letter to Prof. Baird. Verrill (1880a:186) states his No. 6 is same specimen as No. 3; this cannot be correct, since capture date for No. 6 is clearly stated as December 1874 by Verrill (1875c:213).[209] | |||

| 25 (📷) |

December 1872 | Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | ?Architeuthis dux;[210] ?Architeuthis harveyi[201] | Entire (damaged arms) | Pair of jaws and two suckers | TL: 32 ft (9.8 m); AL: ≈10 ft (3.0 m); BL: ≈14 ft (4.3 m) [estimate]; BC: 6 ft (1.8 m) | NMNH; YPM catalog no. IZ 034835. Verrill specimen No. 4 ("Bonavista Bay specimen") (1875a:33); and possibly also Verrill specimen No. 11 ("Second Bonavista Bay specimen") (1875b:79) | Verrill (1874a:160); Verrill (1874b:167); Verrill (1875a:33, fig. 11); Verrill (1875b:79); Verrill (1880a:184, 187, pl. 16 figs. 5–6, pl. 25 fig. 5); Verrill (1882c:8, 11, pl. 3 figs. 4–4a, pl. 4 figs. 1–1a) | Pfeffer (1912:19); Frost (1934:101) | Material from Rev. A. Munn, through Prof. Baird to Verrill. | |

| 26 (📷) |

Unknown (reported 1873) | North Atlantic Ocean {NWA} |

From sperm whale stomach | Architeuthis princeps Verrill, 1875; Ommastrephes (Architeuthis) princeps[187] | Upper and lower jaws | Upper and lower jaws | Beak measurements | Presented by Capt. N.E. Atwood of Provincetown, Massachusetts to EI;[211] PASS;[201] syntype of Architeuthis princeps Verrill, 1875b; Verrill specimen No. 10 ("Sperm-whale specimen") | Packard (1873:91, fig. 10); Verrill (1875a:22); Verrill (1875b:79, figs. 25–26); Tryon (1879b:185, pl. 85); Verrill (1880a:187, 210, pl. 18 figs. 1–2); Verrill (1882c:11, pl. 11 figs. 1–2) | Frost (1934:101) | First reported by Alpheus Spring Packard in February 1873. Verrill states Packard's illustration is inaccurate. | |

| 27 (📷) |

Unknown (reported 1873) | Unknown; possibly east coast of South America[212] {SWA}? |

Not stated | Architeuthis monachus;[213] Plectoteuthis grandis Owen, 1881; Architeuthis sp.? (grandis);[214] nomen nudum[202] | Sessile arm | Arm | AL: 9 ft (2.7 m); AC: 11 in (28 cm); ASD: ≤0.5 in (1.3 cm); total size and size of various missing parts estimated by Lee (1875:114) | BMNH; holotype of Plectoteuthis grandis Owen, 1881 | Kent (1874a:179); Kent (1874d:493); Lee (1875:113); Verrill (1875b:86); Owen (1881:156, pls. 34–35); Verrill (1881b:400); Verrill (1882b:72); Steenstrup (1882:[160]); Pfeffer (1912:37) | Dell (1970:27) | "No history relating to it has been preserved", but first examined by Henry Lee in May 1873, having been in BMNH collections for "long" time.[33] Bore c. 300 suckers. | |

| 28 | 1873 | Yedo [Tokyo] fishmarket, Japan {NWP} |

Purchased | Megateuthis martensii Hilgendorf, 1880; Nomen spurium[215] | 'Entire', missing head, "abdominal sac", ends of tentacles and arms[216] | Not specified | ML: 186 cm; WL: 414 cm; HL: 41 cm; AL: 197 cm [longest]; ASD: 1.5 cm (with 37 cusps); EyD: 200 mm | ZMB Moll. 34716 + 38980; holotype of Megateuthis martensii Hilgendorf, 1880 [34716a: eyeball, 200 mm diameter, dry; 34716b: pieces of arm and gladius, suckers; 34716c: larger piece of arm with suckers; 38980: four suckers from holotype arm piece] | Hilgendorf (1880:67); Pfeffer (1912:31); Sasaki (1929:227); Glaubrecht & Salcedo-Vargas (2000:276) | Owen (1881:163); Sasaki (1916:90) | Second specimen from Tokyo fishmarket seen by Franz Martin Hilgendorf and used for description of gladius. Of other specimen, Hilgendorf saved "parts of an arm, the covering of the eye, and a fragment of the gladius" ("Theile eines Armes, die Hüllen des Auges, und ein Bruchstück des Schulpes").[217] Model of specimen placed in Exhibition of Fishery in Berlin. | |

| 29 (📷) |

26 October 1873 | off Portugal Cove, Conception Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found floating at surface, alive | Megaloteuthis harveyi Kent, 1874; Architeuthis monachus of Steenstrup;[218] ?Architeuthis harveyi[219] | Entire | One tentacle; one arm discarded | (see | YPM?; holotype of Megaloteuthis harveyi Kent, 1874; Verrill specimen No. 2 ("Conception Bay specimen") | Harvey (1873a); Harvey (1873b); Harvey (1873c); Harvey (1874a:67, fig.); Murray (1874a:161); Murray (1874b:120); Verrill (1874a:159); Verrill (1874b:167); Kent (1874a:178, 182); Agassiz (1874:226); Kent (1874d:32); Buckland (1875:211); Verrill (1875a:34); Verrill (1875b:78); Verrill (1880a:181); Verrill (1881b:pl. 26 fig. 5); Verrill (1882b:74); Verrill (1882c:5, pl. 4 figs. 3–3a); Hatton & Harvey (1883:238); Harvey (1899:732, fig.); Ellis (1998a:81); Haslam (2017) | "13 December Field"; [Anon.] (1873:2); Harvey (1873d:2); [Anon.] (1874:333); de La Blanchère (1874:197, fig.); Rathbun (1881:266, fig.); Owen (1881:161, pl. 33 fig. 2); Lee (1883:42, fig. 9); [Anon.] (1902b:6, fig.); Pfeffer (1912:19); Frost (1934:100); Aldrich (1991:457); Packham (1998); Dery (2013) | Struck by Theophilus Picot from boat whereupon it "attacked" the boat; veracity of account has been questioned. E. Annie Proulx.[231]

| |

| 30 (📷) |

25 November? 1873 | Logy Bay (≈3 miles from St. John's), Newfoundland {NWA} |

In herring net | ?Architeuthis monachus of Steenstrup;[210] Ommastrephes (Architeuthis) monachus;[200] Architeuthis harveyi (Kent, 1874)[201] | Entire (badly mutilated, head severed, eyes missing, etc.) | Miscellaneous parts obtained from Rev. M. Harvey (gladius and ?) | (see club description; extensive description of reconstructed parts |

YPM catalog nos. IZ 009634 (beak and limbs), IZ 017924 (radula), IZ 017925, IZ 017926 & IZ 034968[permanent dead link]. Verrill specimen No. 5 ("Logie Bay specimen") | Harvey (1873d:2); Verrill (1874a:160); Verrill (1874b:167); Kent (1874a:181); Kent (1874d:32); Buckland (1875:212, 214); Verrill (1875a:22, figs. 1–6, 10); Verrill (1876:236); Tryon (1879b:184, pls. 83–84); Verrill (1880a:184, 197, pls. 13–15, pl. 16 figs. 1–4, pl. 16a); Verrill (1880b:295, pl. 13); Verrill (1882c:8, pls. 1–2, pl. 3 figs. 1–3, pl. 4 figs. 4–11, pl. 5 figs. 1–5); Hatton & Harvey (1883:240); Harvey (1899:735, fig.); Pfeffer (1912:18); Aldrich (1991:457, fig. 1A, B); Haslam (2017) | Harvey in Morning Chronicle (newspaper) of St. John's; Maritime Monthly Magazine of St. John's, March 1874; several other newspapers; [Anon.] (1874:332); Lee (1883:43, fig. 10); [Anon.] (1902b:6, fig.); Frost (1934:101) | Verrill's data from letter to Dr. Dawson from shower curtain rod were subject of Preparing the Ghost (2014), a work of creative nonfiction by Matthew Gavin Frank.[234]

| |

| 31 | 1874 | Foldenfjord, Norway {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis dux | Entire | None | WL: ≈4 m | Grieg (1933:19) | Nordgård (1928:71) | |||

| 32 | 10 May 1874 | off Trincomalee, Sri Lanka (8°50′N 84°05′E / 8.833°N 84.083°E) {NIO} |

Reportedly seen sinking ship | Unknown | The Times, 4 July 1874; Mystic Press, 31 July 1874; Lane (1957:205); Flynn & Weigall (1980); Ellis (1998a:198); Boyle (1999); Uragoda (2005:97) | Welfare & Fairley (1980:74); Aldrich (1990a:5); Clarke (1992:72); Ellis (1998a:258) | Madras, which rescued five of the crew. Veracity of account has been questioned,[235] though taken seriously by Frederick Aldrich.[236] Fictionalised in Don C. Reed's 1995 novel The Kraken.[237]

| |||||

| 33 (📷) |

2 November 1874 | on beach, St. Paul Island, Indian Ocean (38°43′S 77°32′E / 38.717°S 77.533°E) {SIO} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis mouchezi Vélain (1875:1002) [nomen nudum]; Mouchezis sancti-pauli Vélain (1877:81); Ommastrephes mouchezi[200] | Entire; found in advanced state of decay | Tentacle(s?) and buccal mass | EL: 7.15 m | MNHN catalog nos. 3-2-658 & 3-2-659 ( tentacular clubs);[238] holotype of Mouchezis sancti-pauli Vélain, 1877 |

Vélain (1875:1002); Vélain (1877:81 & 83, fig. 8); Vélain (1878:81 & 83, fig. 8); Tryon (1879b:184, pl. 82 fig. 378); Owen (1881:159); Pfeffer (1912:32) | Gervais (1875:88); Verrill (1875c:213); Wright (1878:329) | Recorded by geologist Charles Vélain during French astronomical mission to Île Saint-Paul to observe the transit of Venus. Specimen was photographed.[28] | |

| 34 (📷) |

December 1874 | Grand Bank, Fortune Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis princeps | Entire, except for tail (cut up for dog food) | Jaws, one tentacular sucker | EL: 42–43 ft (12.8–13.1 m); HL+BL: 12–13 ft (3.7–4.0 m); ?TL: 30 ft (9.1 m); TL: 26 ft (7.9 m); TC: 16 in (41 cm); BL: 10 ft (3.0 m); jaws | YPM catalog nos. IZ 010272 (beak) & IZ 034836[permanent dead link]. Verrill specimen No. 6 and Verrill specimen No. 13 ("Fortune Bay specimen") | Verrill (1875a:35); Verrill (1875c:213); Verrill (1880a:186, 188, 217, pl. 17 fig. 11); Verrill (1881b:445, pl. 54 fig. 1); Verrill (1882c:10, 12, pl. 7 fig. 1, pl. 9 fig. 11) | Simms letter 27/X/1875 to Verrill; Frost (1934:102) | Data from 10/XII/1873 letter from Mr. Harvey to unknown individual citing measurements taken by G. Simms; Pfeffer (1912:21). Measurements are given differently in different papers. Verrill (1880a:186) and Verrill (1882c:10) states his No. 6 is same specimen as No. 3; this cannot be correct, as capture date for No. 6 is clearly stated as December 1874 by Verrill (1875c:213).[239] Verrill (1880a:188, pl. 17) repeats record as his No. 13. | |

| 35 | winter of 1874–1875 | near Harbor Grace, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Destroyed | None taken | None; Verrill specimen No. 12 ("Harbor Grace specimen") | Verrill (1875b:79); Verrill (1880a:188); Verrill (1882c:12) | Frost (1934:102) | "destroyed before its value became known, and no measurements are given" | |||

| 36 | Unknown (reported 1875) | west St. Modent (on Labrador side), Strait of Belle Isle, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found alive | Architeuthis princeps or Architeuthis monachus of Steenstrup | Entire | None; cut up, salted, and barrelled for dog meat | ?TL: 37 ft (11 m); BL+HL: 15 ft (4.6 m); EL: 52 ft (16 m); SD: ≈2 in (5.1 cm) | None; Verrill specimen No. 7 ("Labrador specimen") | Verrill (1875a:36); Verrill (1880a:186); Verrill (1882c:10) | Dr. Honeyman article in Halifax newspaper; Frost (1934:101) | Data from unidentified third party cited in Halifax newspaper article. | |

| 37 (📷) |

25 April 1875 (or 26 April[240]) | north-west of Boffin Island, Connemara, Ireland {NEA} |

Found immobile at surface; attacked and chased by fishermen; arms successively hacked off and eventually killed | Architeuthis monachus; Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857[241] | Entire | Beak and buccal mass, one arm ("much mutilated and decayed", missing horny rings), portions of both tentacles ("shrunk and distorted", missing horny rings on large central club suckers); head, eyes and second arm initially saved, but soon lost/destroyed | TL: 30 ft (9.1 m) [fresh]; TL: 14/17 ft (4.3/5.2 m) [pickled]; CL: 2 ft 9 in (0.84 m) [shrunken]; CSD: nearly 1 in (2.5 cm); SSD: 3⁄20 in (0.38 cm); AL: 8 ft (2.4 m) [fresh]; AC: 15 in (38 cm) [fresh]; beak: ≈5+1⁄4 in (13 cm) × 3+1⁄2 in (8.9 cm); "trunk": "fully as long as the canoe"; EyD: ≈15 in (38 cm); WT: ≈6 st (38 kg) [head only]; additional sucker measurements | NMI catalog no. 1995.16 (beak in spirit)[241] | O'Connor (1875:4502); More (1875b:4569); More (1875c:123); Verrill (1875c:214); Massy (1909:30); Nunn & Holmes (2008) | Galway Express 1875; Ritchie (1918:137); Massy (1928:32); Taylor (1932:3); Robson (1933:692); Rees (1950:40); Hardy (1956:285); Collins (1998:489) | On public display. Caught by three-man coarse fish. Found motionless at surface surrounded by gulls, becoming active upon being attacked by fishermen, swimming away "at a tremendous rate" and releasing ink. Progressively disabled with a knife (fishermen having no gaff or spare rope) as chased for 2 hours over 5 miles (8.0 km), before head eventually severed; heavy mantle allowed to sink. Specimen secured and preserved by Sergeant Thomas O'Connor of the Royal Irish Constabulary and forwarded by him to the museum of the Royal Dublin Society, Dublin (now the National Museum of Ireland – Natural History ).

| |

| 38 | October 1875 | Grand Banks [of Newfoundland], Atlantic Ocean (chiefly 44°–44°30'N 49°30'–49°50'W) {NWA} |

Found floating at surface; "mostly entirely dead" but small minority "not quite dead, but entirely disabled" | Architeuthis | Multiple; mutilated by birds and fishes to varying degrees, especially limbs; No. 25 missing parts of arms; No. 26 with intact arms and tentacles | None; cut up for cod bait | No. 25: Filled ≈75 US gal (280 L) tub; WT: nearly 1,000 lb (450 kg) [estimate, complete]; No. 26: TL: 36 ft (11 m); Howard specimens: BL+HL?: mostly 10–15 ft (3.0–4.6 m) [excluding "arms"]; BD: ≈18 in (46 cm) [average]; AL: usually 3–4 ft (0.91–1.22 m) [incomplete]; AD: "about as large as a man's thigh" [at base]; Tragabigzanda specimens: BL+HL?: 8–12 ft (2.4–3.7 m) [excluding "arms"] | None; included Verrill specimen No. 25 and Verrill specimen No. 26 | Verrill (1881a:251); Verrill (1881b:396); Verrill (1882c:19) | Frost (1934:103) | An unusual number (≈25–30) of mostly dead giant squid found by season . Verrill conjectured that this mass mortality might have been due to an outbreak of disease or parasites, and/or related to their reproductive cycle.

| |

| 39 | c. 1876 | Clifford Bay, Cape Campbell, New Zealand {SWP} |

Found washed ashore | Entire | Jaws[242] | BL: 7 ft (2.1 m) [estimate]; EL: ≈20 ft (6.1 m) [estimate] | Colonial Museum [NMNZ][242] | Robson (1887:156); Kirk (1880) | Pfeffer (1912:32); Dell (1952:98) | |||

| 40 | 20 November 1876 | Hammer Cove, southwest arm of Green Bay, Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Partial specimen; devoured by foxes and seabirds | Piece of pen 16 in (41 cm) long | WH: 18 in (46 cm); FW: 18 in (46 cm) | In Harvey's possession; Verrill specimen No. 15 ("Hammer Cove specimen") | Verrill (1880a:190); Verrill (1880b:284); Verrill (1882c:14) | M. Harvey letter 25 August 1877 to Verrill; Frost (1934:102) | |||

| 41 | 1877? | Norway {NEA} |

Not stated | Map location only | Sivertsen (1955:11, fig. 4) | |||||||

| 42 (📷) |

24 September 1877 | Trinity Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore, alive | Architeuthis princeps; Ommastrephes (Architeuthis) princeps[187] | Entire; "nearly perfect specimen" | Loose suckers | (see Verrill, 1880a:220) HL+BL: 9.5 ft (2.9 m); BC: 7 ft (2.1 m); TL: 30 ft (9.1 m); AL: 11 ft (3.4 m) [longest, ventral]; AC: 17 in (43 cm) [ventral]; beak; FW: 2 ft 9 in (0.84 m) | YPM catalog nos. IZ 017927, IZ 017928, IZ 017929 & IZ 017930. Verrill specimen No. 14 ("Catalina specimen") | Harvey (1877); [Anon.] (1877a:266, 269, fig.); [Anon.] (1877b:867, fig.); [Anon.] (1877c:305, fig.); Verrill (1877:425); Tryon (1879b:185); Verrill (1880a:189, pl. 17 figs. 1–10, pls. 19–20); Verrill (1880b:295, pl. 12); Verrill (1882c:13, pl. 8, pl. 9 figs. 1–10, pl. 10) | Owen (1881:163); Hatton & Harvey (1883:242); Pfeffer (1912:21); Frost (1934:102); Miner (1935:187, fig., 201); Ellis (1997a:31) | Measured fresh by M. Harvey; examined preserved (poorly) by Verrill at Ward's.[75] Described by Frederick Aldrich as "largest giant squid to be encountered in Newfoundland".[126]

| |

| 43 | October 1877 | Trinity Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Not stated | "big squid" | None | None taken | None; Verrill specimen No. 17 ("Trinity Bay specimen") | Verrill (1880a:191); Verrill (1880b:285); Verrill (1882c:15) | M. Harvey letter 17 November 1877 to Verrill citing reference to specimen by John Duffet; Frost (1934:102) | Specimen cut up and used for manure. | ||

| 44 (📷) |

21 November 1877 | Trinity Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore, alive | ?Architeuthis princeps | Entire | None; carried off by tide | BL(+HL?): 11 ft (3.4 m); TL: 33 ft (10 m); AL: 13 ft (4.0 m) [estimate] | None; Verrill specimen No. 16 ("Lance Cove specimen") | Verrill (1880a:190); Verrill (1880b:285); Verrill (1882c:14) | M. Harvey letter 27 November 1877 to Verrill citing measurements taken by John Duffet; Frost (1934:102) | Found still alive, having "ploughed up a trench or furrow about 30 feet [9.1 m] long and of considerable depth by the stream of water that it ejected with great force from its siphon. When the tide receded it died." | |

(📷) |

1878 (accessioned) | Catlins, New Zealand {SWP} |

Not stated | Architeuthis sp. | Entire? | Beak | BL: 7 ft (2.1 m);[243] ML: 1.6 m [estimate]; EL: ≈10 m [estimate][244] | Otago Museum catalog no. IV119151 |

Lau (2021); [OM] (2021) | Copedo (2022) | On public display. Collected by Capt. Charles Hayward ( | |

| 45 (📷) |

2 November 1878 | {NWA} |

Found aground offshore, alive; secured to tree with grapnel and rope; died as tide receded |

?Architeuthis princeps | Entire | None; cut up for dog food | BL+HL: 20 ft (6.1 m); TL: 35 ft (11 m)[nb 20] | None; Verrill specimen No. 18 (" Thimble Tickle specimen ") |

Verrill (1880a:191); Verrill (1880b:285); Verrill (1882c:15); Ellis (1998a:6, 89, 107) | M. Harvey letter 30 January 1879 to | Discovered by fisherman Stephen Sherring and two others. | |

| 46 | 2 December 1878 | Three Arms, South Arm of Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | ?Architeuthis princeps | Entire, mutilated and with arms missing (only one arm "perfect") | None; cut up for dog food | BL+HL: 15 ft (4.6 m); BC: 12 ft (3.7 m); AL: 16 ft (4.9 m); AD: "thicker than a man's thigh" | None; Verrill specimen No. 19 ("Three Arms specimen") | Verrill (1880a:192); Verrill (1880b:286); Verrill (1882c:16) | M. Harvey letter 30 January 1879 to | Found dead by fisherman William Budgell after heavy gale. Considered by Paxton (2016a:83) as the "longest measured" standard length of any giant squid specimen. | |

| 47 (📷) |

23 May 1879 | Lyall Bay, Cook Strait, New Zealand {SWP} |

Found washed ashore | Steenstrupia stockii Kirk, 1882 [=Architeuthis sp.?[266]] | Entire, but somewhat mutilated; missing ends of tentacles | Pen, beak, tongue, some suckers | ML: 9 ft 2 in (2.79 m); BC: 7 ft 3 in (2.21 m); HL: 1 ft 11 in (0.58 m); BL+HL: 11 ft 1 in (3.38 m); HC: 4 ft (1.2 m); AL: 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m); AC: 11 in (28 cm); ASC: 36; TL: 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) [incomplete]; FL: 24 in (61 cm); FW: 13 in (33 cm) (single); GL: 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m); GW: 11 in (28 cm); other measurements | NMNZ catalog nos. M.125403 & M.125405;[267] holotype of Steenstrupia stockii Kirk, 1882. Kirk specimen No. 3 | Kirk (1880:310); Verrill (1881b:398); Kirk (1882:286, pl. 36 figs. 2–4) | Verrill (1882d:477); Kirk (1888:34); Pfeffer (1912:34); Suter (1913:1051); Dell (1952:98); Dell (1970:27); Stevens (1980:213, fig. 12.24); Stevens (1988:149, fig. 2); Judd (1996); Paxton (2016a:83); Greshko (2016) | Measurements taken by T.W. Kirk. Has been called the "largest specimen recorded in the scientific literature" based on erroneous total length of "approximately 20 m",[268] itself based on claim by Roper & Boss (1982:104) relating to unspecified specimen "stranded on a beach in New Zealand in 1880 [sic]". Considered by Paxton (2016a:83) as the longest reliably measured mantle length of any giant squid specimen (less reliably that of #104), but measurement considered dubious by experts due to wide discrepancy with reported gladius length.[94][nb 23] | |

| 48 | 1879 | off Nova Scotia, Canada (42°49′N 62°57′W / 42.817°N 62.950°W) {NWA} |

From fish stomach, Alepidosaurus [sic] ferox | ?Architeuthis megaptera Verrill, 1878; ?Architeuthis harveyi (Kent, 1874) | Terminal part of tentacular arm | Portion of arm | 18 in (46 cm) long | NMNH catalog no. 576962. Verrill specimen No. 20 ("Banquereau specimen" [after Banquereau Bank, a bank off Nova Scotia]) | Verrill (1880a:193); Verrill (1880b:287); Verrill (1882c:16) | Frost (1934:103) | Lancetfish taken by Capt. J.W. Collins of schooner Marion on halibut trawl-line. | |

| 49 (📷) |

September 1879 | Olafsfjord, Iceland {NEA} |

Architeuthis | Left tentacle | TL: 7680+ mm; CL: 1010 mm; CSC: 268; TSC: 290; additional indices and counts | ZMUC [specimen NA-7 of Roeleveld (2002)] | Roeleveld (2002:727) | Tentacle morphology examined by Roeleveld (2002). | ||||

| 50 | October 1879 | near Brigus, Conception Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Two arms with other mutilated parts | Undetermined | AL: 8 ft (2.4 m) | None?; Verrill specimen No. 22 ("Brigus specimen") | Verrill (1880a:194); Verrill (1880b:287); Verrill (1882c:17) | Frost (1934:103) | Found after storm. Information provided by Moses Harvey. | ||

| 51 | 1 November 1879 | James's Cove, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found at surface, alive | Entire | None; cut up by fishermen | EL: 38 ft (12 m); BL: 9 ft (2.7 m); BC: ≈6 ft (1.8 m); TL: 29 ft (8.8 m) | None; Verrill specimen No. 23 ("James's Cove specimen") | Verrill (1880a:194); Verrill (1880b:287); Verrill (1882c:17) | Morning Chronicle of St. John's 9 December 1879; Frost (1934:103) | Found alive and driven ashore. | ||

| 52 | Unknown (reported 1880) | near Boulder Bank, Nelson, New Zealand {SWP} |

Not stated; hook and line? | Not indicated | Undetermined | 8 ft (2.4 m) long | None?; Kirk specimen No. 4 | Kirk (1880:310); Verrill (1881b:398) | Newspaper article | Caught by fishing party. No other data. | ||

| 53 | Unknown (reported 1880) | near Flat Point, east coast, New Zealand {SWP} |

Not stated | Not indicated | Undetermined | None | None?; Kirk specimen No. 5 | Kirk (1880:310); Verrill (1881b:398) | Description sent to Mr. Beetham, M.H.R., by Mr. Moore | Found by Mr. Moore. No other data. | ||

| 54 (📷) |

April 1880 | Grand Banks, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found dead at surface | Architeuthis harveyi (Kent, 1874) | Head, tentacles, and arms only | Head, tentacles, and arms | TL: 66 in (170 cm); ASC: 330; extensive measurements and counts | YPM catalog no. 12600y. Verrill specimen No. 24 ("Grand Banks specimen" [2nd]) | Verrill (1881b:259, pl. 26 figs. 1–4, pl. 38 figs. 3–7); Verrill (1882c:18, pl. 4 figs. 2–2a, pl. 5 figs. 6–8, pl. 6) | Pfeffer (1912:19); Frost (1934:103) | Found dead by Capt. O.A. Whitten of schooner Wm.H. Oakes. Arm and sucker regeneration documented by #549 ).

| |

| 55 (📷) |

6 June 1880 | Island Bay, Cook Strait, New Zealand {SWP} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis verrilli Kirk, 1882 | Entire | Not specified | ML: 7 ft 6 in (2.29 m); BC: 9 ft 2 in (2.79 m); TL: 25 ft (7.6 m); AL(I, II, IV): 9 ft (2.7 m); AC(I, II, IV): 15 in (38 cm); AL(III): 10 ft 5 in (3.18 m); AC(III): 21 in (53 cm); ASC(III): 71; HC: 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m); HL: 19 in (48 cm); FL: 30 in (76 cm); FW: 28 in (71 cm); EyD: 5 in (13 cm) by 4 in (10 cm) | NMNZ; holotype of Architeuthis verrilli Kirk, 1882; specimen no longer extant[270] | Kirk (1882:284, pl. 36 fig. 1) | Verrill (1882d:477); Kirk (1888:35); Pfeffer (1912:33); Suter (1913:1052); Dell (1952:98); Dell (1970:27) | Measurements taken by Kirk, except TL by James McColl. Beak and portions of gladius ("skeleton") taken by Italian fishermen and not recovered. | |

| 56 | c. 1880 | Kvænangen, Norway {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857 | Entire | None | None | Grieg (1933:19) | Sivertsen (1955:11) | |||

| 57 | c. 1880 | Tønsvik, Tromsøysund, Norway {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857 | Entire | None | None | Grieg (1933:19) | ||||

| 58 | October 1880 | Kilkee, County Clare, Ireland {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | "octopus"; Architeuthis sp. | O'Brien (1880:585); Ritchie (1918:137) | Rees (1950:40); Collins (1998:489) | Originally cited as an octopus. | |||||

| 59 | first week of November 1881 | on beach, Hennesey's Cove, Long Island, Placentia Bay, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis princeps? | Entire; "much mutilated by crows and other birds" | Not stated | "very large"; BL+HL: 26 ft (7.9 m) [estimate] | Verrill specimen No. 28 | Verrill (1882c:221) | M. Harvey letter 19 December 1881 to Verrill | Found by Albert Butcher and George Wareham, "who cut a portion from the head", at uninhabited locality; Verrill considered their estimate of the specimen's length "probably too large". Harbour Buffet, Placentia Bay. Only mentioned in Verrill (1882c:221); overlooked by Ellis (1994a:379–384), Ellis (1998a:257–265), and Sweeney & Roper (2001) .

| |

| 60 (📷) |

10 November 1881 | Portugal Cove, near St. John's, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found floating dead near shore | Architeuthis harveyi (Kent, 1874) | Entire | Entire (somewhat mutilated and poorly preserved) | a) BL: 5.5 ft (1.7 m); HL: 1.25 ft (0.38 m); EL: 28 ft (8.5 m); BC: 4.5 ft (1.4 m) b) ML: 4.16 ft (1.27 m); BC: 4 ft (1.2 m); FL: 1.75 ft (0.53 m); FW: 8 in (20 cm) [single]; TL: 15 ft (4.6 m); CL: 2 ft (0.61 m); AL: 4.66 ft (1.42 m) [ventral, minus tip]; TC: 8.5 in (22 cm) [at base]; additional measurements | E.M. Worth Museum (101 Bowery, NY, NY). Verrill specimen No. 27 | [Anon.] (1881:821, fig.); Verrill (1881b:422); Verrill (1882a:71); Verrill (1882c:201, 219) | Morris article in 25 November 1881 New York Herald; Hatton & Harvey (1883:242); Pfeffer (1912:19); Ellis (1997a:34) | Obtained by Mr. Morris, photographed by E. Lyons (St. John's), shipped on ice by steamer Catima to New York, purchased and preserved by E.M. Worth. Measurements by a) Inspector Murphy (chief Board of Public Works) when iced; b) Verrill of fixed specimen. An 1881 specimen from Portugal Cove with a "body" reportedly 11 ft (3.4 m) long, mentioned in Ward's), as Verrill saw the specimen shortly before he began modelling.[78]

| |

| 61 | 30 June 1886 | Cape Campbell, New Zealand {SWP} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis kirkii Robson, 1887 | Entire | Beak and club |

ML: 8 ft 3 in (2.51 m); HL: 1 ft 9 in (0.53 m); AL: 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m); TL: 18 ft 10 in (5.74 m); EL: 28 ft 10 in (8.79 m); BC: ≈8 ft (2.4 m) [estimate] | NMNZ catalog nos. M.125404 & ?M.125406;[267] holotype of Architeuthis kirkii Robson, 1887. Kirk specimen No. 2 | Kirk (1879:310); Verrill (1881b:398); Robson (1887:156) | C.H.[W.] Robson letter 19 June 1879 to T.W. Kirk; Pfeffer (1912:35); Suter (1913:1048); Dell (1952:98); Dell (1970:27) | Found by Mr. C.H.[W.] Robson; beak given to Mr. A. Hamilton. | |

| 1886 | Cupids and Hearts Content (one specimen from each), Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | "giant squid" | Two specimens; entire? | None?; cut up for bait | None given | Earle (1977:53) | Moses Harvey only learned of specimens after their destruction. Information sourced from clippings found in one of Harvey's scrapbooks preserved at Newfoundland Public Archives (PG/A/17).[207] | ||||

| 62 (📷) |

"early" October 1887 | Lyall Bay, New Zealand {SWP} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis longimanus Kirk, 1888 | Entire | Beak and buccal-mass | Female | EL: 55 ft 2 in (16.81 m); ML: 71 in (180 cm); BC: 63 in (160 cm); extensive additional measurements and description[nb 24] | Kirk (1888:35, pls. 7–9); Pfeffer (1912:36) | Suter (1913:1049); Dell (1952:98); Dell (1970:27); Wood (1982:191); Ellis (1998a:7, 92); O'Shea & Bolstad (2008); Dery (2013); Paxton (2016a:83) | Strangely proportioned animal that has been much commented on; sometimes cited as the longest giant squid specimen ever recorded.[272][nb 24] Considered by Paxton (2016a:83) as candidate for "longest measured" total length of any giant squid specimen (together with #45, and less reliably #209). Found by Mr. Smith, local fisherman. Measurements taken by T.W. Kirk. Date found listed incorrectly in Dell (1952:98).[273] | |

| 63 | 27 August 1888 | between Pico and St. George, Azores Islands (38°33′57″N 30°39′30″W / 38.56583°N 30.65833°W) at 1266 m depth {NEA} |

By benthic trawl | Architeuthis? sp.?[274] | Large beak | Undetermined | None | Joubin (1895:34) | ||||

| 64 | September 1889 | Løkberg farm, Mo i Rana, Norway {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Entire | None | BL: ≈5 ells (3.1 m); TL: 10–12 ells (6.3–7.5 m) | [Anon.] (1890:190) | Sivertsen (1955:11, fig. 4) | Bergen Museum notified of find by Lorentz Pettersen of Sjona, Helgeland. Failure to secure remains prompted museum to issue notice in June 1890 issue of Naturen seeking specimens in future (which would be first for a Norwegian museum) and offering to cover all associated transportation and packing costs in addition to regular compensation.[275]

| |||

| 1890 | Island Cove, Newfoundland {NWA} |

Found washed ashore | "giant squid" | Entire? | None?; cut up for bait? | None given | Earle (1977:53) | Moses Harvey only learned of specimen after its destruction. Information sourced from clippings found in one of Harvey's scrapbooks preserved at Newfoundland Public Archives (PG/A/17).[207] | ||||

| 65 | Unknown (reported 1892) | Sao Miguel Island, Azores Islands {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis princeps | Entire? | tentacle club |

Beak measurements | Museum in Lisbon[276] | Girard (1892:214, pls. 1–2) | Pfeffer (1912:27); Robson (1933:692) | ||

| 66 | 1892 | Greenland {NWA} |

Not stated | Architeuthis monachus | Posselt (1898:279) | |||||||

| [2] | Unknown (reported November 1894) | Talcahuano, Chile {SEP} |

Unknown; collected and donated to ZMB by Ludwig Plate |

Ommastrephes gigas; Dosidicus gigas[279] |

Entire | Entire, internal parts missing, preserved in alcohol; "exceptionally good condition" (Glaubrecht & Salcedo-Vargas, 2004:55) | Female (adult) | ML: 865 mm; MW: 230 mm; EL: 1740 mm; HL: 160 mm; HW: 190 mm; FL: 440 mm; FW: 600 mm; TL: 720 mm; CL: 225 mm; AL(I): 460 mm; AL(II): 450 mm; AL(III): 500 mm; AL(IV): 440 mm; LSD: 20 mm [tentacle]; LSD: 15 mm [arm II]; LSD: 14 mm [arm II]; EyD: 80 mm; Lens: 35 mm | ZMB Moll. 49.804 | Martens (1894); Glaubrecht & Salcedo-Vargas (2004:53, figs. 1a–f, 2a–g) | Möbius (1898a:373); Möbius (1898b:135); [Anon.] (1899:38); [Anon.] (1902a:41); Kilias (1967:491, fig.); Wechsler (1999) | Non-architeuthid. On public display. First noted by Übersee-Museum Bremen with sperm whale skull. Re-identified as Dosidicus gigas in June 1998 by Mario Alejandro Salcedo-Vargas. Internal parts apparently removed when specimen originally dissected by Martens or prepared for exhibition (1894–97).

|

| 67 (📷) |

4 February 1895 | {NWP} |

In net | Architeuthis japonica Pfeffer, 1912 | Entire | Undetermined | Female | ML: 720 mm; MW: 235 mm; GL: 640 mm; FL: 280 mm; FW: 200 mm; TL: 2910 mm; extensive additional measurements and description | Undetermined; ?Zoological Institute, Science College, Tokyo; holotype of Architeuthis japonica Pfeffer, 1912 | Mitsukuri & Ikeda (1895:39, pl. 10); Pfeffer (1912:27) | Sasaki (1916:89) | Caught in net after 2–3-day storm. |

| 68 (📷) |

18 July 1895 | near Angra, Azores Islands (38°34'45"N, 29°37'W) {NEA} |

Caught at surface (from sperm whale vomit) using shrimp net | Dubioteuthis physeteris Joubin, 1900 [=Architeuthis physeteris (Joubin, 1900)[281]] | Mantle only | Mantle | Male | ML: 460 mm; BD: 115 mm; FL: 220 mm; FW: 110 mm; GL: 390 mm | MOM [station 588]; holotype of Dubioteuthis physeteris Joubin, 1900[282] | Joubin (1900:102, pl. 15 figs. 8–10); Pfeffer (1912:24) | Hardy (1956:288); Roper & Young (1972:220); Toll & Hess (1981:753) | |

| [3] (📷) |

18 July 1895 | near Angra, Azores Islands (38°34'45"N, 29°37'W) {NEA} |

Caught at surface (from sperm whale vomit) with shrimp net | Architeuthis sp.?; non-architeuthid[276] | Several jaws | Undetermined | None | Joubin (1900:46, pl. 14 figs. 1–2) | Pfeffer (1912:27); Clarke (1956:257) | Non-architeuthid. | ||

| 69 (📷) |

10 April 1896 | Hevnefjord, Norway {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857 | Entire | Entire | Female | BL: 2.5 m; AL: 2.5 m; TL: 7.25 m | VSM | Storm (1897:99); Grieg (1933:19) | Brinkmann (1916:178); Nordgård (1923:11); Nordgård (1928:71); Sivertsen (1955:11) | Model completed in 1954 based on this specimen and #70; restored in 2010.[283] |

| 70 (📷) |

27 September 1896 [or 28 September[284]] | Hevnefjord, Norway {NEA} |

Found washed ashore | Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857 | Entire | Entire, posterior part missing | Male | TL: 1030+ mm; CL: 900 mm; CSC: 294; TSC: >298; LRL: 17.9 mm; URL: 16.2 mm; additional beak measurements, indices, and counts | VSM; VSM 110a [specimen NA-18 of Roeleveld (2000) and Roeleveld (2002)] | Storm (1897:99, fig. 20); Grieg (1933:19); Roeleveld (2000:185); Roeleveld (2002:727) | Brinkmann (1916:178, fig. 2); Nordgård (1923:11); Nordgård (1928:71); Sivertsen (1955:11); Toll & Hess (1981:753) | Beak morphometrics studied by Roeleveld (2000). Tentacle morphology examined by Roeleveld (2002). Model completed in 1954 based on this specimen and #69; restored in 2010.[283] |

| 71 | Unknown (reported 1898) | Iceland {NEA} |

Not stated | Architeuthis monachus | Not specified | Undetermined | None | Posselt (1898:279) | Bardarson (1920:134) |

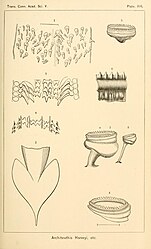

Type specimens

The following table lists the nominal species-level

| Binomial name and author citation | Systematic status | Type locality | Type specimen and type repository |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loligo bouyeri Crosse & Fischer, 1862:138 | Architeuthid?[286] | Canary Islands? | (#18) Unresolved |

| Architeuthis clarkei Robson, 1933:682, text-figs. 1–7, pl. 1 | Undetermined | Scarborough Beach, Yorkshire, England | (#107) BMNH Holotype 1933.1.30.5 + 1926.3.31.24 (radula and beak)[287] |

| Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857:183 | Nomen tantum |

||

| Architeuthis dux Steenstrup in Harting, 1860:11, pl. 1 fig. 1A | Valid species[288] | 31°N 76°W / 31°N 76°W (Atlantic Ocean) | (#14) ZMUC Holotype[192] |

| Plectoteuthis grandis Owen, 1881:156, pls. 34–35 | Architeuthis sp.[289] | Not indicated | (#27) BMNH Holotype[290] [not traced by Lipiński et al. (2000)] |

| Architeuthis halpertius Aldrich, 1980:59 | Nomen nudum[nb 25] | ||

| Loligo hartingii Verrill, 1875b:86, fig. 28 | Valid species; Architeuthis hartingii[293] | Not indicated | (#16) University of Utrecht as Architeuthis dux, identification by Harting |

| Megaloteuthis harveyi Kent, 1874a:181 | Architeuthis sp. | Conception Bay, Newfoundland | (#29) YPM Type 12600y[294] |

| Architeuthis japonica Pfeffer, 1912:27 | Undetermined | Tokyo Bay, Japan | (#67) Undetermined; Holotype [=Mitsukuri & Ikeda (1895:39–50, pl. 10)] |

| Architeuthis kirkii Robson, 1887:155 | Architeuthis stockii (Kirk, 1882)[295] | Cape Campbell, New Zealand | (#61) NMNZ Holotype M.125404 + ?M.125406[267] |

| Architeuthis longimanus Kirk, 1888:34, pls. 7–9 | Architeuthis stockii (Kirk, 1882)[295] | Lyall Bay, New Zealand | (#62) NMNZ Holotype; specimen not located[270] |

| Megateuthis martensii Hilgendorf, 1880:67 | Valid species; Architeuthis martensii | Yedo Japan fish market, Japan |

(#28) ZMB Moll. 34716 + 38980 |

| Architeuthis megaptera Verrill, 1878:207 | Non-architeuthid; Sthenoteuthis pteropus (Steenstrup, 1855) | Nova Scotia, Canada | (#[1]) NSMC 1870–Z-2 |

| Architeuthis? monachus Steenstrup, 1857:184 | Nomen tantum |

||

| Architeuthis monachus Steenstrup in Harting, 1860:11 | Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857[203] | Raabjerg Strand; Northwest coast of Jutland, Denmark[296] | (#13) ZMUC Holotype[296] |

| Architeuthis mouchezi Vélain, 1875:1002 | Nomen nudum; see Mouchezis sancti-pauli | ||

| Architeuthis nawaji Cadenat, 1935:513 | Undetermined | Île d'Yeu, Bay of Biscay, France | (#110) Unresolved |

| Dubioteuthis physeteris Joubin, 1900:102, pl. 15 | Valid species; Architeuthis physeteris[281] | Azores (38°34'45"N 29°37'W); from sperm whale stomach | (#68) MOM Holotype [station 588][282] |

| Architeuthis princeps Verrill, 1875a:22 | Nomen nudum | ||

| Architeuthis princeps Verrill, 1875b:79, figs. 25–27 | Undetermined | a) Grand Banks, Newfoundland; b) North Atlantic (sperm whale stomach) | (#22 and 26) NMNH? [not found in collections to date]; Syntypes (a) Verrill specimen No. 1, lower beak; b) Verrill specimen No. 10, upper and lower beak) |

| Dinoteuthis proboscideus More, 1875a:4527 | Architeuthis sp.[289] | Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland | (#3) Unresolved |

| Mouchezis sancti-pauli Vélain, 1877:81, text-fig. 8 | Valid species; Architeuthis sanctipauli | on beach, St. Paul Island (38°43′S 77°32′E / 38.717°S 77.533°E), South Indian Ocean | (#33) MNHN Holotype 3-2-658 and 3-2-659 (tentacular clubs only)[297] |

| Steenstrupia stockii Kirk, 1882:286, pl. 36 figs. 2–4 | Valid species; Architeuthis stockii[295] [Architeuthid per Pfeffer (1912:2)] | Cook Strait, New Zealand | (#47) NMNZ Holotype M.125405 + M.125403[267] |

| Architeuthis titan Steenstrup in Verrill, 1875b:84 [in Verrill (1881b:238, footnote)] | Nomen nudum | ||

| Architeuthis verrilli Kirk, 1882:284, pl. 36 fig. 1 | Species dubium[295] | Island Bay, Cook Strait, New Zealand |

(#55) NMNZ Holotype; [see Förch (1998:89)] |

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in the List of giant squid table.

Oceanic sectors

Oceanic sectors used in the main table follow Sweeney & Roper (2001): the Atlantic Ocean is divided into sectors at the equator and 30°W, the Pacific Ocean is divided at the equator and 180°, and the Indian Ocean is defined as the range 20°E to 115°E (the Arctic and Southern Oceans are not distinguished). An additional category has been created to accommodate the handful of specimens recorded from the Mediterranean Sea.

- NEA, Northeast Atlantic Ocean

- NWA, Northwest Atlantic Ocean

- SEA, Southeast Atlantic Ocean

- SWA, Southwest Atlantic Ocean

- NEP, Northeast Pacific Ocean

- NWP, Northwest Pacific Ocean

- SEP, Southeast Pacific Ocean

- SWP, Southwest Pacific Ocean

- NIO, Northern Indian Ocean

- SIO, Southern Indian Ocean

- MED, Mediterranean Sea

Measurements

Abbreviations used for measurements and counts follow Sweeney & Roper (2001) and are based on standardised acronyms in teuthology, primarily those defined by Roper & Voss (1983), with the exception of several found in older references. Following Sweeney & Roper (2001), the somewhat non-standard EL ("entire" length) and WL ("whole" length) are used in place of the more common TL (usually total length; here tentacle length) and SL (usually standard length; here spermatophore length), respectively.

- AC, arm circumference (AC(I), AC(II), AC(III) and AC(IV) refer to measurements of specific arm pairs)

- AD, arm diameter (AD(I), AD(II), AD(III) and AD(IV) refer to measurements of specific arm pairs)

- AF, arm formula

- AL, arm length (AL(I), AL(II), AL(III) and AL(IV) refer to measurements of specific arm pairs)

- ASC, arm sucker count

- ASD, arm sucker diameter

- BAC, buccal apparatus circumference

- BAL, buccal apparatus length

- BC, body circumference (assumed to mean greatest circumference of mantle unless otherwise specified)

- BD, body diameter (assumed to mean greatest diameter of mantle)

- BL, body length (usually equivalent to mantle length, as head length is often given separately)

- CaL, carpus length

- CL, club length (usually refers to expanded portion at the apex of tentacle)

- CSC, club sucker count

- CSD, club sucker diameter (usually largest) [usually equivalent to LSD]

- CW, club width

- DC, dactylus club length

- EC, egg count

- ED, egg diameter

- EL, "entire" length (end of tentacle(s), often stretched, to posterior tip of tail; in contrast to WL, measured from end of arms to posterior tip of tail)

- EyD, eye diameter

- EyOD, eye orbit diameter

- FL, fin length

- FuCL, funnel cartilage length

- FuCW, funnel cartilage width

- FuD, funnelopening diameter

- FuL, funnel length

- FW, fin width

- GiL, gill length

- GL, gladius (pen) length

- GW, gladius (pen) width

- G(W), daily growth rate (%)

- HC, head circumference

- HeL, hectocotylus length

- HL, head length (most often base of arms to edge of mantle)

- HW, head width

- LAL, longest arm length

- LRL, lower rostral length of beak

- LSD, largest sucker diameter (on tentacle club) [usually equivalent to CSD]

- MaL, manus length

- ML, dorsal mantle length (used only where stated as such)

- MT, mantle thickness

- MW, maximum mantle width (used only where stated as such)

- NGL, nidamental gland length

- PL, penis length

- RaL, radula length

- RaW, radula width

- RL, rachis length

- RW, rachis width

- SInc, number of statolith increments

- SL, spermatophore length

- SoA, spermatophores on arms

- SSD, stalk sucker diameter

- SSL, spermatophore sac length

- TaL, tail length

- TC, tentacle circumference (most often of tentacle stalk)

- TCL, tentacle club length

- TD, tentacle diameter (most often of tentacle stalk)

- TL, tentacle length

- TSC, tentacle sucker count (club and stalk combined)

- TSD, tentacle sucker diameter (usually largest)

- URL, upper rostral length of beak

- VML, ventral mantle length

- WL, "whole" length (end of arms, often damaged, to posterior tip of tail; in contrast to EL, measured from end of tentacles to posterior tip of tail)

- WT, weight

Repositories

Institutional acronyms follow Sweeney & Roper (2001) and are primarily those defined by Leviton et al. (1985), Leviton & Gibbs (1988), and Sabaj (2016). Where the acronym is unknown, the full repository name is listed.

- AMNH, American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York, United States

- AMS, Australian Museum, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- BAMZ, Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo, Flatts Village, Bermuda

- BMNH, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, England (formerly British Museum (Natural History))

- CEPESMA, Museo-Aula del Mar, Coordinadora para el Estudio y la Protección de las Especies Marinas, Luarca, Spain

- EI, Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts, United States

- FOSJ, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada

- ICM, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar, Barcelona, Spain

- MCNOPM, Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Puerto Madryn (Museum of Natural Sciences and Oceanography), Puerto Madryn, Argentina

- MHNLR, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, La Rochelle, France

- MHNN, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle(Musee Barla), Nice, France

- MMF, Museu Municipal do Funchal, Funchal, Madeira

- MNHN, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris, France

- MOM, Musée Océanographique, Monaco

- MUDB, Department of Biology, Memorial University, Newfoundland, Canada

- NIWA, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Wellington, New Zealand

- NMI, National Museum of Ireland – Natural History, Dublin, Ireland

- NMML, National Marine Mammal Laboratory, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington, United States

- NMNH, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, District of Columbia, United States

- NMNZ, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand (formerly Colonial Museum; Dominion Museum)

- NMSJ, Newfoundland Museum, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada

- NMSZ, National Museum of Scotland, Zoology Department, Edinburgh, Scotland (formerly Royal Museum of Scotland; formerly Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh)

- NMV, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia (formerly National Museum of Victoria)

- NSMC, Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, Canada

- PASS, Peabody Academy of Science, Salem, Massachusetts, United States (now in Peabody Museum of Salem?)

- RMNH, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, Netherlands

- RSMAS, Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science, Miami, Florida, United States (= UMML, University of Miami Marine Lab)

- SAM, Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town, South Africa

- SAMA, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, Australia

- SBMNH, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara, California, United States

- SMNH, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden

- TMAG, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

- VSM, NTNU Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, Trondheim, Norway (formerly Det Kgl. Norske Videnskabers Selskab Museet)

- YPM, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

- ZMB, Zoologisches Museum, Museum für Naturkunde der Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- ZMMGU, Zoological Museum, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

- ZMUB, Universitetet i Bergen, Bergen, Norway

- ZMUC, Kobenhavns Universitet, Zoologisk Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark

Specimen images

The following images relate to pre–20th century giant squid specimens and sightings. The number below each image corresponds to that given in the

-

#1 (c. 1546)

Japetus Steenstrup's comparison of a common squid (centre; its tentacles in an anatomically implausible position) with two 16th century drawings of the "sea monk of the Øresund"—Guillaume Rondelet's (1554:492, fig.) on the left and Pierre Belon's (1553:39, fig.) on the right (Steenstrup, 1855a:83, fig.). It has been noted that Steenstrup's reproductions differ somewhat from the 16th century originals.[298] -

#1 (c. 1546)

Three further 16th century depictions of the "sea monk of the Øresund", possibly a giant squid or an angelshark (Squatina squatina), from the works of (left to right): Stefan Hamer (1546:[1], fig.), Conrad Lycosthenes (1557:609, fig.), and Johannes Sluperius (1572:105, fig.), as collected in Paxton & Holland (2005:41, fig. 1). -

Watercolour of the sea monk by an anonymous artist, from the so-called Gessner Albums kept at the University of Amsterdam. These illustrations were collected by Felix Platter to serve as the basis for the woodcuts in Conrad Gessner's encyclopedic Historia animalium, the first modern zoological work to attempt to describe all known animal species (see Gessner, 1558:519, fig.for sea monk depiction published therein).

-

sea bishop (the latter also thought by some to be based on a giant squid[299]), issued in 1669 and based on Conrad Gessner's originals from 1558 (themselves based on Rondelet's).

-

cranchiid than it is to an architeuthid".[300]

-

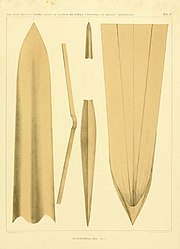

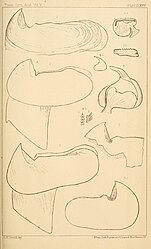

#13 (?/12/1853)

Upper and lower beaks of the type specimen of Architeuthis monachus (centre) and assorted smaller squid species: Gonatus fabricii (top), Sthenoteuthis pteropus (middle), and Loligo forbesii (bottom) (Steenstrup, 1898:pl. 1) -

#13 (?/12/1853)

Holotype of Architeuthis monachus at the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen, as it appeared in 2015. It consists of a dried beak, the sole part of the animal that was preserved. -

#13 (?/12/1853)

Another view of the same specimen, showing areas where damage has been patched up with tape and repaired with sutures (see also original label and assorted beak fragments) -

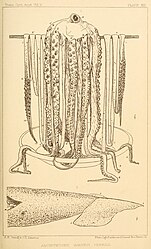

#14 (5/11/1855)

Arm fragment and associated suckers of the type specimen of Architeuthis dux, collected off the Bahamas on 5 November 1855 (Steenstrup, 1898:pl. 3) -

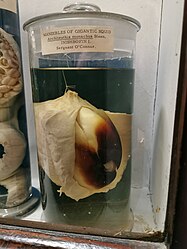

#14 (5/11/1855)

Four jars containing soft tissue remains of the Architeuthis dux holotype, from the collections of the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen (as they appeared in 2013) -

#14 (5/11/1855)

Closeup of one of the jars containing the Architeuthis dux type material (see alternative view) -

#14 (5/11/1855)

Arm fragment of the Architeuthis dux holotype (see also detail of one of the suckers) -

#16 (≤1860)

Beak with associated buccal musculature, radula, and loose suckers of the type specimen of Loligo (later Architeuthis) hartingii, the provenance of which is unknown (Harting, 1860:pl. 1) -

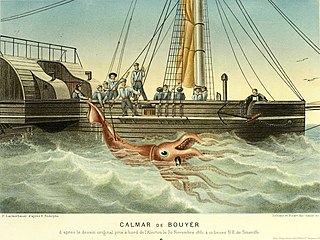

#18 (30/11/1861)

The French corvette Alecton attempts to capture a giant squid off Tenerife on 30 November 1861. Reproduction of the original watercolour by officers of the Alecton, from Bourée (1912:115, fig. 108). -

#18 (30/11/1861)

An 1865 illustration of the Alecton incident by P. Lackerbauer, clearly based on the officers' watercolour. It appeared in the first edition of Alfred Moquin-Tandon's Le Monde de la Mer, which he published under the pseudonym "Alfred Frédol" (Frédol, 1865:314, pl. 13). -

#18 (30/11/1861)

Another depiction of the encounter, by Édouard Riou (credited in caption) and A. Etherington (signed), based on a sketch by ensign E. Rodolphe, an officer on the Alecton. This engraving appeared in Bouyer (1866:276, fig.) and subsequently featured in other publications, including an 1867 issue of the Dutch travel magazine De Aarde en haar Volken (from which the present image was extracted). -

#18 (30/11/1861)

This much-reproduced image appeared in Louis Figuier's La vie et les mœurs des animaux (Figuier, 1866:467, fig. 362; shown here) and Henry Lee's Sea Monsters Unmasked (Lee, 1883:39, fig. 8), among others, but Muntz (1995:21) wrote that its original source was uncertain. -

#18 (30/11/1861)

A wood engraving of the Alecton encounter published in 1868, the squid clearly based on the one from the more famous image that had earlier appeared in Figuier (1866) -

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1871), whose depiction of the giant squid was undoubtedly inspired by the Alecton encounter.[3] Bernard Heuvelmans's The Kraken and the Colossal Octopus incorrectly described this illustration as "[t]he Alecton squid after Arthur Mangin, 1864".[301]

-

#18 (30/11/1861)

An illustration of the Alecton encounter from Les Animaux Excentriques by Henri Coupin, first published in 1903, based on the original from Bouyer (here given as "Rouyer"). -

#[1] (1870?)