Kingdom of Italy (Napoleonic)

Kingdom of Italy | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1805–1814 | ||

Romagnol | ||

| Religion | Catholic | |

| Demonym(s) | Italian | |

| Government | Unitary absolute monarchy | |

| King | ||

• 1805–1814 | Napoleon I | |

Viceroy | ||

• 1805–1814 | Eugène de Beauharnais | |

| Legislature | Napoleon I | 23 May 1805 |

| 26 December 1805 | ||

| 8 February 1814 | ||

| 11 April 1814 | ||

| 30 May 1814 | ||

| Currency | Italian lira | |

| ISO 3166 code | IT | |

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

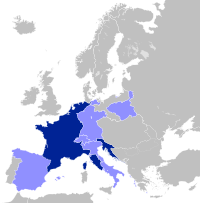

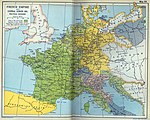

The Kingdom of Italy (Italian: Regno d'Italia; French: Royaume d'Italie) was a kingdom in Northern Italy (formerly the Italian Republic) in personal union with Napoleon's French Empire. It was fully influenced by revolutionary France and ended with Napoleon's defeat and fall. Its government was assumed by Napoleon as King of Italy and the viceroyalty delegated to his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais. It covered some of Piedmont and the modern regions of Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Trentino, South Tyrol, and Marche. Napoleon I also ruled the rest of northern and central Italy in the form of Nice, Aosta, Piedmont, Liguria, Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, but directly as part of the French Empire (in the departements), rather than as part of a vassal state.

Constitutional statutes

The Kingdom of Italy was born on 17 March 1805, when the

Even though the republican constitution was never formally abolished, a series of Constitutional Statutes completely altered it. The first one was proclaimed two days after the birth of the kingdom, on 19 March,[2] when the Consulta declared Napoleon I as king and established that one of his natural or adopted sons would succeed him once the Napoleonic Wars were over, and once separated the two thrones were to remain separate. The second one, dating from 29 March, regulated the regency, the Great Officials of the kingdom, and the oaths.

The most important was the third, proclaimed on 5 June, being the real constitution of the kingdom: Napoleon I was the head of state and had the full powers of government; in his absence, he was represented by the Viceroy, Eugène de Beauharnais. The Consulta, Legislative Council, and Speakers were all merged into a Council of State, whose opinions became only optional and not binding for the king. The Legislative Body, the old parliament, remained in theory, but it was never summoned after 1805; the Napoleonic Code was introduced on 21 March 1804.[3]

The fourth Statute, decided on 16 February 1806, indicated Beauharnais as the heir to the throne.[2]

The fifth and the sixth Statutes, on 21 March 1808, separated the Consulta from the Council of State, and renamed it the Senate, with the duty of informing the king about the wishes of his most important subjects.[2]

The seventh Statute, on 21 September, created a new nobility of dukes, counts and barons; the eighth and the ninth, on 15 March 1810, established the annuity for the members of the royal family.

The government had seven ministers:

- The Minister of War was at first General Augusto Caffarelli, later General Giuseppe Danna for a year, and then, from 1811, General Achille Fontanelli;

- The Ludovico Arborio di Breme and then, from 1809, Luigi Vaccari;

- The Minister for Foreign Affairs was Ferdinando Marescalchi;

- The Minister of Justice and Great Judge was Giuseppe Luosi;

- The Minister of the Treasury was Antonio Veneri and then, from 1811, Ambrogio Birago;

- The Minister of Finance was Giuseppe Prina;

- The Minister of Religion was Giovanni Bovara.

Image gallery

-

Napoleon I,

King of Italy

(1805–1814) -

Eugène de Beauharnais,

Viceroy of Italy

(1805–1814) -

Augusto Caffarelli,

Minister of War

(1806–1810) -

Achille Fontanelli,

Minister of War

(1811–1813) -

Ferdinando Marescalchi,

Minister of Foreign Affairs

(1805–1814) -

Giuseppe Luosi,

Minister of Justice

(1805–1814)

Territory

Originally, the Kingdom consisted of the territories of the Italian Republic: the former

After the defeat of the

With the Convention of Fontainebleau with Austria of 10 October 1807, Italy ceded

The conquered Republic of Ragusa was annexed in spring 1808 by General Auguste de Marmont. On 2 April 1808, following the dissolution of the Papal States, the Kingdom annexed the present-day Marches. At its maximum extent, the Kingdom had 6,700,000 inhabitants and was composed by 2,155 comunes.

The final arrangement arrived after the defeat of Austria in the War of the Fifth Coalition: Emperor Napoleon and King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria signed the Treaty of Paris on 28 February 1810, deciding an exchange of territories involving Italy too.

On rewards in Germany, Bavaria ceded southern Tyrol to the Kingdom of Italy, which in turn ceded Istria and Dalmatia (with Ragusa) to France, incorporating the Adriatic territories into newly created the French Illyrian Provinces. Small changes to the borders between Italy and France in Garfagnana and Friuli came in act on 5 August 1811.

In practice, the Kingdom was a dependency of the French Empire.[4]

The Kingdom served as a theater in Napoleon's operations against Austria during the wars of the various

Currency

Regno d'Italia (1808)

Regno d'Italia (1812)

The kingdom was given a new national currency, replacing the local coins circulating in the country: the Italian lira, of the same size, weight, and metal of the French franc.[5] Mintage being decided by Napoleon with an imperial decree on 21 March 1806, the production of the new coins began in 1807. The monetary unit was the silver lira, which was 5 grams heavy. There were multiples of £2 (10 grams of silver) and £5 (25 grams of silver), and precious coins of £20 (6.45 grams of gold) and £40 (12.9 grams of gold). The lira was basically divided in 100 cents, and there were coins of 1 cent (2.1 grams of copper), 3 cents (6.3 grams of copper), and 10 cents (2 grams of poor silver), but following the tradition, there was a division in 20 soldi, with coins of 1 soldo (10.5 grams of copper, in practice 5 cents), 5 soldi (1.25 grams of silver), 10 soldi (2.5 grams of silver), and 15 soldi (3.75 grams of silver).

Army

The army of the kingdom, inserted into the Grande Armée, took part in all of Napoleon's campaigns. In the course of its existence from 1805 to 1814 the Kingdom of Italy provided Napoleon I with roughly around 200,000 soldiers.[6][7]

In 1805 Italian troops served on garrison duty along the

In 1809,

In 1812, Eugène de Beauharnais marched 27,000 troops of the Kingdom of Italy into Russia.[12] The Italian contingent distinguished themselves at Borodino and Maloyaroslavets,[13][14] receiving the recognition:[15]

"The Italian army had displayed qualities which entitled it evermore to take rank amongst the bravest troops of Europe."

Only 1,000–2,000 Italians survived the Russian campaign, but they returned with most of their banners secured.[12][16] In 1813, Eugène de Beauharnais held out as long as possible against the onslaught of the Austrians[13] (Battle of the Mincio) and was later forced to sign an armistice in February 1814.[17]

-

Troop uniforms of the Kingdom of Italy, 1805–14

-

Military parade in 1812

Infantry:

- Line infantry: five regiments from the Italian Republic, with two more later raised, in 1805 and 1808.

- Light infantry: three regiments from the Italian Republic, plus another one raised in 1811.

- Royal Guard: two battalions from the Italian Republic (Granatieri and Cacciatori), plus other two (Velites) raised in 1806, plus two battalions of young guard raised in 1810, and another two raised in 1811.

Cavalry:

- Dragoons: two regiments from the Italian Republic.

- Cacciatori a Cavallo (light horse): one regiment from the Italian Republic, plus three others, raised in 1808, 1810, and 1811.

- Royal Guard: two squadrons of dragoons, five companies of Guards of Honour.[18]

Local administration

The administrative system of the Kingdom was firstly drawn by a law on 8 June 1805. The state was divided, following the French system, in 14

The departments were divided in districts, equivalent to the French

The cantons were divided in

During the kingdom's life, the administrative system of the State changed for domestic and international reasons. Following the defeat of Austria and the

Language and education

The language used officially in the Kingdom of Italy was Italian. The French language was used for ceremonies and in all relationships with France.

Education was made universal for all children, which was also conducted in Italian. By decree of the governor Vincenzo Dandolo, this was so even in Istria and Dalmatia, where local populations were more heterogeneous.[20]

List of departments and districts

During its last maximum extension (from 1809 to 1814), the Kingdom lost Istria/Dalmatia but got added Bolzano/Alto Adige and consisted of 24 departments.[21]

- Adda (capital Sondrio)

- No districts

- Adige (capital Verona)

- Agogna (capital Novara)

- Alto Adige (capital Trento)

- Crostolo (capital Reggio Emilia)

- Lario (capital Como)

- Lower Po (capital Ferrara)

- Mella (capital Brescia)

- Mincio (capital Mantua)

- Olona (capital Milan)

- Panaro (capital Modena)

- Reno (capital Bologna)

- Rubicone (capital Cesena)

- Serio (capital Bergamo)

- Upper Po (capital Cremona)

- Adriatico (capital Venice)

- Bacchiglione (capital Vicenza)

- Brenta (capital Padua)

- Istria

- Passariano (capital Udine)

- Piave (capital Belluno)

- Tagliamento (capital Treviso)

- Metauro (capital Ancona)

- Musone (capital Macerata)

- Tronto (capital Fermo)

Decline and fall

When Napoleon abdicated both the thrones of France and Italy on 11 April 1814, Eugène de Beauharnais was lined up on the Mincio river with his army to repel any invasion from Germany or Austria, and he attempted to be crowned king. The Senate of the Kingdom was summoned on 17 April, but the senators showed themselves undecided in that chaotic situation. When a second session of the assembly took place on 20 April, the Milan insurrection foiled the Viceroy's plan. In the riots, finance minister Count Giuseppe Prina was massacred by the crowd, and the Great Electors disbanded the Senate and called the Austrian forces to protect the city, while a Provisional Regency Government under the presidency of Carlo Verri was appointed.

Eugène surrendered on 23 April, and was exiled to Bavaria by the Austrians, who occupied Milan on 28 April. On 26 April, the Empire appointed

See also

References

- ^ Desmond Gregory, Napoleon's Italy (2001)

- ^ a b c d "Statuti Costituzionali del Regno d'Italia (1805 al 1810)". www.dircost.unito.it.

- ^ Robert B. Holtman, The Napoleonic Revolution (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981)

- ^ Napoleon Bonaparte, "The Economy of the Empire in Italy: Instructions from Napoleon to Eugène, Viceroy of Italy," Exploring the European Past: Texts & Images, Second Edition, ed. Timothy E. Gregory (Mason: Thomson, 2007), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Equal to the franc, the new Napoleonic lira had a different value face to the old, ancient Milanese lira. Distinguishing the two different coins, people began to refer to the new coin as franc. So, through the years, people in north-western Italy continued to call franc the lira in their local dialects until the changeover with euro in 2002. [1]

- ^ Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the Present. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gregory, Desmond (2001). Napoleon's Italy: Desmond Gregory. AUP Cranbury.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Elting, John R. (1988). Swords around a throne. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Scott, Sir Walter (1843). Life of Napoleon Buonaparte: Vol.4. Edinburgh.

- ^ Thiers, Adolphe (1856). History of the consulate and the empire of France under Napoleon: Vol.13. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Arnold, James R. (1995). Napoleon conquers Austria: the 1809 campaign for Vienna. Westport.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b John A. Davis, Paul Ginsborg (1991). Society and Politics in the Age of the Risorgimento. Cambridge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ISBN 9780852291627.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2006). The encyclopedia of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars: Vol.1. Santa Barbara.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wilson, Sir Robert Thomas (1860). Narrative of events during the invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Montagu, Violette M. (1913). Eugène de Beauharnais: the adopted son of Napoleon. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A–E. Westport.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Antonio Virgili, La Tradizione napoleonica, CSI, Napoli, 2005

- ^ Historical name changes can create confusion: the present-day Italian province of South Tyrol (called in Italian Alto Adige) does not cover the same area as the Napoleonic Alto Adige, which mainly correspondeds to the province of Trentino including the city of Bolzano with its Southern surroundings.

- ^ Sumrada, Janez. Napoleon na Jadranu / Napoleon dans l'Adriatique.pag.37

- ^ "Map of the Kingdom of Italy in 1808, when Ragusa in Dalmatia was part of the "Albania" department".

Further reading

- Connelly, Owen. Napoleon's Satellite Kingdoms (1965)

- Gregory, Desmond. Napoleon's Italy (2001)

- Rath, R. John. The Fall of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy (1814) (1941)

External links

- Napitalia. The Eagle in Italy about the army of the Kingdom of Italy under Napoleon.