User:Imbehind/sandbox

Evolucija je naziv za proces uslijed kojeg dolazi do promjena nasljednih osobina bioloških populacija tijekom velikog broja uzastopnih generacija.[1][2] Evolucijski procesi dovode do bioraznolikosti na svakom nivou biološke organizacije, uključujući nivoe vrsta, individualnih organizama i molekula.[3]

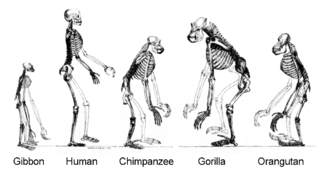

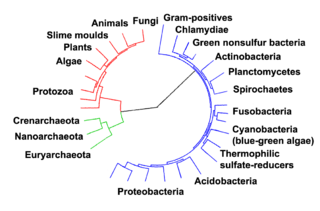

Neprestano formiranje novih vrsta (specijacija), promjene unutar vrsta (anageneza) i nestanak vrsta (izumiranje) tijekom cijele evolucijske povijesti života na Zemlji obilježeno je pojavom brojnih zajedničkih morfoloških i biokemijskih osobina organizama, uključujući i međusobno identične sekvence DNK.[4] Ove zajedničke osobine su sličnije među vrstama koje dijele nedavnog zajedničkog pretka i mogu se koristiti kako bi rekonstruirali biološko "stablo života" zasnovano na evolucijskim poveznicama (filogenetika) koristeći kako postojeće žive vrste tako i fosile. Fosilni zapisi u sebi uključuju prikaz prograsije u razvoju živoga svijeta od ranog biogenog grafita,[5] preko fosila mikrobnih naslaga ,[6][7][8] do fosiliziranih višestaničnih organizama. Svi danas postojeći oblici bioraznolikosti su oblikovani procesima specijacije, ali i izumiranja.[9]

Sredinom 19. stoljeća Charles Darwin je postavio znanstvenu Teoriju evolucije putem prirodnog odabira koju je objavio u svojoj knjizi Postanak vrsta (1859) te ga zbog toga danas smatramo ocem kako Teorije o evoluciji tako i moderne biologije. Iako Teorija evolucije ne objašnjava kako je život nastao, u potpunosti objašnjava svu raznolikost života koju danas susrećemo i smatra se najvažnijom teorijom iz područja znanosti o životu na kojoj se temelje sva suvremena istraživanja i znanstvene spoznaje u biologiji. Iz temeljnih postulata teorije evolucije nužno proizlazi i teorija o zajedničkom porijeklu odnosno pretpostavlja postojanje posljednjeg univerzalnog zajedničkog pretka, životnog oblika koji je živio prije 3.5 - 3.8 milijardi godina i koji predak svim danas poznatim živim vrstama.[10][11][12][5][6][8] Teoriju o univerzalnom zajedničkom porijeklu je također prvi formulirao Darwin.

Evolucija putem prirodnog odabira je proces koji je temeljen na opažanju da živi svijet u pravilu proizvodi ukupno više potomstva nego što to potomstvo ima mogućnost preživljavanja te na činjenicama koje znamo o populaciji: 1) osobine variriaju među jedinkama u smislu morfologije, fiziologije i ponašanja (fenotipska varijacija), 2) različite varijacije uzrokuju različite stope preživljavanja i reprodukcije (diferencijalna prilagođenost) i 3) osobine se mogu prenositi iz generacije u generaciju (nasljeđivanje sposobnosti preživljavanja).[13] Zbog toga su jedinke u svakoj novoj generaciji neke populacije zamijenjene potomstvom onih roditelja koji su bolje prilagođeni i imaju veće šanse za preživljavanje i razmnožavanje u okolišu u kojem se prirodan odabir odvija.

Spomenuti način djelovanja evolucije stvara privid svrhovitosti ili usmjerenosti ka cilju samog procesa prirodnog odabira koji naizgled ciljano stvara i prilagođava nužne osobine organizma funkcionalnoj ulozi koju obavljaju (telenomija).[14] Procesi po kojima se promjene odvijaju iz generacije u generaciju nazivamo evolucijskim procesima i mehanizmima.[15] Četiri najčešće spominjana mehanizma su su prirodan odabir (uključujući i seksualnu selekciju), genetski otklon, mutacije i genetski tok uslijed genetskih primjesa. Mutacije i genetski tok uzrokuju varijacije, a prirodna selekcija i genetski otklon ih probiru.

Početkom 20. stoljeća moderna evolucijska sinteza je integrirala klasičnu genetiku Gregora Mendela sa Darwinovom Teorijom evolucije putom prirodnog odabira kroz disciplinu populacijske genetike, a ključna važnost prirodnog odabira kao uzroka procesa evolucije je prihvaćena u svim granama biologije. Štoviše, prethodni stavovi i razmišljanja o evoluciji, kao što su ortogeneza, evolucionizam te hipoteze o "prirodnom" smijeru evolucijskog procesa u smislu stalnog trenda uvećanja kompleksnosti živih organizama, postaju suvišni i više se ne smatraju znanstvenima.[16] Znanstvenici nastavljaju proučavati različite aspekte evolucijske biologije postavljajući i testirajući nove hipoteze, stvarajući nove matematičke modele teorijske biologije, kao i biološke teorije, koristeći empirijske podatke, te i dalje provode opsežne eksperimente na terenu i u laboratoriju.

U smislu praktične primjene, naše razumijevanje evolucije je bilo ključno u razvoju brojnih novih znanstvenih disciplina kao i industrijskih polja primjene stečenih spoznaja o evoluciji, uključujući posebno poljoprivredu, ljudsku i veterinarsku medicinu, kao i znanost o životu uopće. [17][18][19] Otkrića u evolucijskoj biologiji značajano su utjecala ne samo na tradicionalne znanstvene discipline na polju biologije nego i na druge akademske discipline, uključujući biološku antropologiju, evolucijsku psihologiju pa čak i na informacijske znanosti, a posebno na razvoj umjetne inteligencije i primjenu genetskih algoritama nastalih na principima Darwinove teorije evolucije na rješavanje problema optimizacije u računalnim znanostima.[20][21]

History of evolutionary thought

Classical times

The proposal that one type of

Medieval

In contrast to these

Pre-Darwinian

In the 17th century, the new

Other naturalists of this time speculated on the evolutionary change of species over time according to natural laws. In 1751, Pierre Louis Maupertuis wrote of natural modifications occurring during reproduction and accumulating over many generations to produce new species.[31] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon suggested that species could degenerate into different organisms, and Erasmus Darwin proposed that all warm-blooded animals could have descended from a single microorganism (or "filament").[32] The first full-fledged evolutionary scheme was Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's "transmutation" theory of 1809,[33] which envisaged spontaneous generation continually producing simple forms of life that developed greater complexity in parallel lineages with an inherent progressive tendency, and postulated that on a local level these lineages adapted to the environment by inheriting changes caused by their use or disuse in parents.[34][35] (The latter process was later called Lamarckism.)[34][36][37][38] These ideas were condemned by established naturalists as speculation lacking empirical support. In particular, Georges Cuvier insisted that species were unrelated and fixed, their similarities reflecting divine design for functional needs. In the meantime, Ray's ideas of benevolent design had been developed by William Paley into the Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity (1802), which proposed complex adaptations as evidence of divine design and which was admired by Charles Darwin.[39][40][41]

Darwinian revolution

The crucial break from the concept of constant typological classes or types in biology came with the theory of evolution through natural selection, which was formulated by Charles Darwin in terms of variable populations. Partly influenced by

Pangenesis and heredity

The mechanisms of reproductive heritability and the origin of new traits remained a mystery. Towards this end, Darwin developed his provisional theory of pangenesis.[48] In 1865, Gregor Mendel reported that traits were inherited in a predictable manner through the independent assortment and segregation of elements (later known as genes). Mendel's laws of inheritance eventually supplanted most of Darwin's pangenesis theory.[49] August Weismann made the important distinction between germ cells that give rise to gametes (such as sperm and egg cells) and the somatic cells of the body, demonstrating that heredity passes through the germ line only. Hugo de Vries connected Darwin's pangenesis theory to Weismann's germ/soma cell distinction and proposed that Darwin's pangenes were concentrated in the cell nucleus and when expressed they could move into the cytoplasm to change the cells structure. De Vries was also one of the researchers who made Mendel's work well-known, believing that Mendelian traits corresponded to the transfer of heritable variations along the germline.[50] To explain how new variants originate, de Vries developed a mutation theory that led to a temporary rift between those who accepted Darwinian evolution and biometricians who allied with de Vries.[35][51][52] In the 1930s, pioneers in the field of population genetics, such as Ronald Fisher, Sewall Wright and J. B. S. Haldane set the foundations of evolution onto a robust statistical philosophy. The false contradiction between Darwin's theory, genetic mutations, and Mendelian inheritance was thus reconciled.[53]

The 'modern synthesis'

In the 1920s and 1930s the so-called

Further syntheses

Since then, the modern synthesis has been further extended to explain biological phenomena across the full and integrative scale of the biological hierarchy, from genes to species. One extension, known as evolutionary developmental biology and informally called "evo-devo," emphasises how changes between generations (evolution) acts on patterns of change within individual organisms (development).[59][60][61] Since the beginning of the 21st century and in light of discoveries made in recent decades, some biologists have argued for an extended evolutionary synthesis, which would account for the effects of non-genetic inheritance modes, such as epigenetics, parental effects, ecological and cultural inheritance, and evolvability.[62][63]

Heredity

Evolution in organisms occurs through changes in heritable traits—the inherited characteristics of an organism. In humans, for example, eye colour is an inherited characteristic and an individual might inherit the "brown-eye trait" from one of their parents.[64] Inherited traits are controlled by genes and the complete set of genes within an organism's genome (genetic material) is called its genotype.[65]

The complete set of observable traits that make up the structure and behaviour of an organism is called its phenotype. These traits come from the interaction of its genotype with the environment.[66] As a result, many aspects of an organism's phenotype are not inherited. For example, suntanned skin comes from the interaction between a person's genotype and sunlight; thus, suntans are not passed on to people's children. However, some people tan more easily than others, due to differences in genotypic variation; a striking example are people with the inherited trait of albinism, who do not tan at all and are very sensitive to sunburn.[67]

Heritable traits are passed from one generation to the next via DNA, a molecule that encodes genetic information.[65] DNA is a long biopolymer composed of four types of bases. The sequence of bases along a particular DNA molecule specify the genetic information, in a manner similar to a sequence of letters spelling out a sentence. Before a cell divides, the DNA is copied, so that each of the resulting two cells will inherit the DNA sequence. Portions of a DNA molecule that specify a single functional unit are called genes; different genes have different sequences of bases. Within cells, the long strands of DNA form condensed structures called chromosomes. The specific location of a DNA sequence within a chromosome is known as a locus. If the DNA sequence at a locus varies between individuals, the different forms of this sequence are called alleles. DNA sequences can change through mutations, producing new alleles. If a mutation occurs within a gene, the new allele may affect the trait that the gene controls, altering the phenotype of the organism.[68] However, while this simple correspondence between an allele and a trait works in some cases, most traits are more complex and are controlled by quantitative trait loci (multiple interacting genes).[69][70]

Recent findings have confirmed important examples of heritable changes that cannot be explained by changes to the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA. These phenomena are classed as epigenetic inheritance systems.[71] DNA methylation marking chromatin, self-sustaining metabolic loops, gene silencing by RNA interference and the three-dimensional conformation of proteins (such as prions) are areas where epigenetic inheritance systems have been discovered at the organismic level.[72][73] Developmental biologists suggest that complex interactions in genetic networks and communication among cells can lead to heritable variations that may underlay some of the mechanics in developmental plasticity and canalisation.[74] Heritability may also occur at even larger scales. For example, ecological inheritance through the process of niche construction is defined by the regular and repeated activities of organisms in their environment. This generates a legacy of effects that modify and feed back into the selection regime of subsequent generations. Descendants inherit genes plus environmental characteristics generated by the ecological actions of ancestors.[75] Other examples of heritability in evolution that are not under the direct control of genes include the inheritance of cultural traits and symbiogenesis.[76][77]

Variation

An individual organism's phenotype results from both its genotype and the influence from the environment it has lived in. A substantial part of the phenotypic variation in a population is caused by genotypic variation.[70] The modern evolutionary synthesis defines evolution as the change over time in this genetic variation. The frequency of one particular allele will become more or less prevalent relative to other forms of that gene. Variation disappears when a new allele reaches the point of fixation—when it either disappears from the population or replaces the ancestral allele entirely.[78]

Natural selection will only cause evolution if there is enough genetic variation in a population. Before the discovery of Mendelian genetics, one common hypothesis was blending inheritance. But with blending inheritance, genetic variance would be rapidly lost, making evolution by natural selection implausible. The Hardy–Weinberg principle provides the solution to how variation is maintained in a population with Mendelian inheritance. The frequencies of alleles (variations in a gene) will remain constant in the absence of selection, mutation, migration and genetic drift.[79]

Variation comes from mutations in the genome, reshuffling of genes through sexual reproduction and migration between populations (gene flow). Despite the constant introduction of new variation through mutation and gene flow, most of the genome of a species is identical in all individuals of that species.[80] However, even relatively small differences in genotype can lead to dramatic differences in phenotype: for example, chimpanzees and humans differ in only about 5% of their genomes.[81]

Mutation

Mutations are changes in the DNA sequence of a cell's genome. When mutations occur, they may alter the product of a gene, or prevent the gene from functioning, or have no effect. Based on studies in the fly Drosophila melanogaster, it has been suggested that if a mutation changes a protein produced by a gene, this will probably be harmful, with about 70% of these mutations having damaging effects, and the remainder being either neutral or weakly beneficial.[82]

Mutations can involve large sections of a chromosome becoming duplicated (usually by genetic recombination), which can introduce extra copies of a gene into a genome.[83] Extra copies of genes are a major source of the raw material needed for new genes to evolve.[84] This is important because most new genes evolve within gene families from pre-existing genes that share common ancestors.[85] For example, the human eye uses four genes to make structures that sense light: three for colour vision and one for night vision; all four are descended from a single ancestral gene.[86]

New genes can be generated from an ancestral gene when a duplicate copy mutates and acquires a new function. This process is easier once a gene has been duplicated because it increases the redundancy of the system; one gene in the pair can acquire a new function while the other copy continues to perform its original function.[87][88] Other types of mutations can even generate entirely new genes from previously noncoding DNA.[89][90]

The generation of new genes can also involve small parts of several genes being duplicated, with these fragments then recombining to form new combinations with new functions.

Sex and recombination

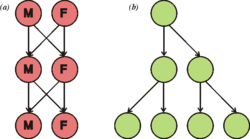

In asexual organisms, genes are inherited together, or linked, as they cannot mix with genes of other organisms during reproduction. In contrast, the offspring of sexual organisms contain random mixtures of their parents' chromosomes that are produced through independent assortment. In a related process called homologous recombination, sexual organisms exchange DNA between two matching chromosomes.[95] Recombination and reassortment do not alter allele frequencies, but instead change which alleles are associated with each other, producing offspring with new combinations of alleles.[96] Sex usually increases genetic variation and may increase the rate of evolution.[97][98]

The two-fold cost of sex was first described by John Maynard Smith.[99] The first cost is that in sexually dimorphic species only one of the two sexes can bear young. (This cost does not apply to hermaphroditic species, like most plants and many invertebrates.) The second cost is that any individual who reproduces sexually can only pass on 50% of its genes to any individual offspring, with even less passed on as each new generation passes.[100] Yet sexual reproduction is the more common means of reproduction among eukaryotes and multicellular organisms. The Red Queen hypothesis has been used to explain the significance of sexual reproduction as a means to enable continual evolution and adaptation in response to coevolution with other species in an ever-changing environment.[100][101][102][103]

Gene flow

Gene flow is the exchange of genes between populations and between species.[104] It can therefore be a source of variation that is new to a population or to a species. Gene flow can be caused by the movement of individuals between separate populations of organisms, as might be caused by the movement of mice between inland and coastal populations, or the movement of pollen between heavy metal tolerant and heavy metal sensitive populations of grasses.

Gene transfer between species includes the formation of

Large-scale gene transfer has also occurred between the ancestors of eukaryotic cells and bacteria, during the acquisition of chloroplasts and mitochondria. It is possible that eukaryotes themselves originated from horizontal gene transfers between bacteria and archaea.[111]

Evolucijski mehanizmi

Iz Neo-Darwinističke perspektive, evolucija nastupa kada postoje promjene u frekvencijama alela unutar populacije organizama u kojoj dolazi do razmjene nasljednog materijala između jediniki. [79] Primjerice, kada alele koje diktiraju crnu boju u populaciji moljaca postanu uobičajene. Mehanizmi koji dovode do promjene u frekvencijama alela uključuju prirodni odabir, genski otklon, gensko stopiranje, mutacije i genski tok.

Prirodna selekcija

Evolucija uslijed prirodne selekcije je proces kojim osobine koje pospješuju preživljavanje i reprodukciju postaju uobičajene sa svakom novom generacijom neke populacije. Često se naziva "samorazumljivim" mehanizmom zato što nužno slijedi iz tri jednostavne i lako provjerljive činjenice:[13]

- U populacijama organizama postoje varijacije u smislu morfologije, fiziologije i ponašanja (fenotipske varijacije).

- Različite osobine organizama dovode do razlika u njihovoj sposobnosti preživljavanja i ramnožavanja (diferencijal prilagođenosti).

- Te osobine mogu biti proslijeđne iz jedne generacije u narednu (nasljeđivanje prilagođenosti).

Više potomstva se proizvodi nego što ga može preživjeti i takvi uvjeti među jedinkama u nekoj populaciji uzrokuju natjecanje za preživljavanje i mogućnost reprodukcije. Zbog toga jedinke sa osobinama koje im donose prednost nad konkurencijom imaju veću vjerojatnost da proslijede te svoje osobine u narednu generaciju od jedinki koje nemaju osobine koje im to omogućavaju.[112]

Centralni koncept teorije evolucije je evolucijska prilagođenost ili sposobnost preživljavanja nekog organizma. [113] Prilagođenost se mjeri sposobnošću organizma da preživi i da se uspješno razmnoži što određuje značaj genskog doprinosa organizma sljedećoj generaciji. [113] Međutim, prilagođenost ne mora biti određena ukupnim brojem potomaka - umjesto toga prilagođenost određujemo udjelom potomaka koji nose gene organizma u narednim generacijama.[114] Kada bi primjerice organizam imao sposobnost uspješnog preživljavanja i brzog razmnožavanja, ali takvu da su njegovi potomci premali i preslabi da bi preživjeli, takav organizam bi imao jako mali genetski doprinos budućim generacijama i imao bi jako nisku ukupnu evolucijsku prilagođenost.[113]

If an allele increases fitness more than the other alleles of that gene, then with each generation this allele will become more common within the population. These traits are said to be "selected for." Examples of traits that can increase fitness are enhanced survival and increased

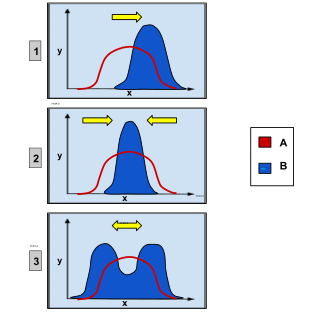

· Graph 1 shows directional selection, in which a single extreme phenotype is favored.

· Graph 2 depicts stabilizing selection, where the intermediate phenotype is favored over the extreme traits.

· Graph 3 shows disruptive selection, in which the extreme phenotypes are favored over the intermediate.

Natural selection within a population for a trait that can vary across a range of values, such as height, can be categorised into three different types. The first is

A special case of natural selection is sexual selection, which is selection for any trait that increases mating success by increasing the attractiveness of an organism to potential mates.[121] Traits that evolved through sexual selection are particularly prominent among males of several animal species. Although sexually favoured, traits such as cumbersome antlers, mating calls, large body size and bright colours often attract predation, which compromises the survival of individual males.[122][123] This survival disadvantage is balanced by higher reproductive success in males that show these hard-to-fake, sexually selected traits.[124]

Natural selection most generally makes nature the measure against which individuals and individual traits, are more or less likely to survive. "Nature" in this sense refers to an

Natural selection can act at different levels of organisation, such as genes, cells, individual organisms, groups of organisms and species.[126][127][128] Selection can act at multiple levels simultaneously.[129] An example of selection occurring below the level of the individual organism are genes called transposons, which can replicate and spread throughout a genome.[130] Selection at a level above the individual, such as group selection, may allow the evolution of cooperation, as discussed below.[131]

Usmjerena mutacija

Osim što je jedan od glavnih uzročnika varijacija, mutacija također može funkcionirati kao evolucijski mehanizam u slučajevima kada na molekularnom nivou postoje različite vjerojatnosti da se točno određena mutacija dogodi. Taj proces nazivamo usmjerenom mutacijom.[132] Primjerice, ako uzmemo dva genotipa, jedan sa nukleotidom G, a drugi sa nukleotidom A na istoj poziciji u DNK sekvenci, ali se mutacija iz G u A događa češće nego mutacija iz A u G, onda će proces evolucije teći na način da će naizgled preferirati genotipove koji sadrže nukleotid A.[133] Sklonost ili pristranost ka umetanju umjesto brisanju nukleotida, ili obrnuto, u različitim taksonima može dovesti do evolucije genotipa različitih veličina.[134][135] Razvojne ili mutacijske sklonosti, odnosno usmjerenja, također su zamijećene u morfološkoj evoluciji.[136][137] Primjerice, sukladno teorijama evolucije koje uzimaju u obzir utjecaj fenotipa na proces evolucije, mutacije mogu uzrokovati gensku asimilaciju osobina koje su uvjetovane od strane okoliša.[138][139][140]

Efekti usmjerene mutacije su superponirani na druge evolucijske procese. Ako prirodni odabir ne favorizira ni jednu od dvije mutacije posebno, ali nema dodatne prednosti da se zadrže i jedna i druga, onda će mutacija koja se događa češće najvjeroatnije biti ona koja će na kraju biti zadržana u populaciji.[141][142] Mutacije koje dovode do gubitka funkcionalnosti gena su znatno uobičajenije od mutacija koje stvaraju nove, potpuno funkcionalne gene. Prirodnim odabirom takve mutacije se obično jako brzo uklanjaju iz genotipa. Međutim, ako je selekcijski pritisak slab, takva mutacija usmjerena prema gubitku genske funkcionalnosti može utjecati na evolucijski proces,[143] Primjerice, geni koji utječu na stvaranje pigmenta u koži organizma koji žive u špiljama ili duboko u oceanima gdje nema svjetla nemaju nikakvu funkciju i vrlo brzo bivaju eliminirani iz genotipa populacije.[144] Ova vrsta gubitka neke funkcije organizma se može dogoditi kako uslijed usmjerene mutacije, tako i/ili zbog toga što je ta funkcija imala i negativne posljedice ili je zahtijevala dodatan utrošak energije organizma. Jednom kada je benefit očuvanja funkcije nestao, prirodna selekcija vodi u gubitak funkcije. Kada prirodni odabir ne favorizira gubitak funkcije, brzina kojom procesom evolucije dolazi do gubitka funkcije ovisi više o učestalosti mutacije nego o efektivnoj veličini populacije,[145] što nam govori da na takve evolucijske promjene više utječe usmjerena mutacija nego genetski otklon.

Genetic drift

Genetic drift is the change in allele frequency from one generation to the next that occurs because alleles are subject to sampling error.[146] As a result, when selective forces are absent or relatively weak, allele frequencies tend to "drift" upward or downward randomly (in a random walk). This drift halts when an allele eventually becomes fixed, either by disappearing from the population, or replacing the other alleles entirely. Genetic drift may therefore eliminate some alleles from a population due to chance alone. Even in the absence of selective forces, genetic drift can cause two separate populations that began with the same genetic structure to drift apart into two divergent populations with different sets of alleles.[147]

It is usually difficult to measure the relative importance of selection and neutral processes, including drift.[148] The comparative importance of adaptive and non-adaptive forces in driving evolutionary change is an area of current research.[149]

The neutral theory of molecular evolution proposed that most evolutionary changes are the result of the fixation of neutral mutations by genetic drift.[150] Hence, in this model, most genetic changes in a population are the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift.[151] This form of the neutral theory is now largely abandoned, since it does not seem to fit the genetic variation seen in nature.[152][153] However, a more recent and better-supported version of this model is the nearly neutral theory, where a mutation that would be effectively neutral in a small population is not necessarily neutral in a large population.[112] Other alternative theories propose that genetic drift is dwarfed by other stochastic forces in evolution, such as genetic hitchhiking, also known as genetic draft.[146][154][155]

The time for a neutral allele to become fixed by genetic drift depends on population size, with fixation occurring more rapidly in smaller populations.[156] The number of individuals in a population is not critical, but instead a measure known as the effective population size.[157] The effective population is usually smaller than the total population since it takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding and the stage of the lifecycle in which the population is the smallest.[157] The effective population size may not be the same for every gene in the same population.[158]

Genetic hitchhiking

Recombination allows alleles on the same strand of DNA to become separated. However, the rate of recombination is low (approximately two events per chromosome per generation). As a result, genes close together on a chromosome may not always be shuffled away from each other and genes that are close together tend to be inherited together, a phenomenon known as linkage.[159] This tendency is measured by finding how often two alleles occur together on a single chromosome compared to expectations, which is called their linkage disequilibrium. A set of alleles that is usually inherited in a group is called a haplotype. This can be important when one allele in a particular haplotype is strongly beneficial: natural selection can drive a selective sweep that will also cause the other alleles in the haplotype to become more common in the population; this effect is called genetic hitchhiking or genetic draft.[160] Genetic draft caused by the fact that some neutral genes are genetically linked to others that are under selection can be partially captured by an appropriate effective population size.[154]

Gene flow

Gene flow involves the exchange of genes between populations and between species.

If genetic differentiation between populations develops, gene flow between populations can introduce traits or alleles which are disadvantageous in the local population and this may lead to organisms within these populations evolving mechanisms that prevent mating with genetically distant populations, eventually resulting in the appearance of new species. Thus, exchange of genetic information between individuals is fundamentally important for the development of the

During the development of the modern synthesis, Sewall Wright developed his shifting balance theory, which regarded gene flow between partially isolated populations as an important aspect of adaptive evolution.[161] However, recently there has been substantial criticism of the importance of the shifting balance theory.[162]

Outcomes

Evolution influences every aspect of the form and behaviour of organisms. Most prominent are the specific behavioural and physical

These outcomes of evolution are distinguished based on time scale as macroevolution versus microevolution. Macroevolution refers to evolution that occurs at or above the level of species, in particular speciation and extinction; whereas microevolution refers to smaller evolutionary changes within a species or population, in particular shifts in gene frequency and adaptation.[164] In general, macroevolution is regarded as the outcome of long periods of microevolution.[165] Thus, the distinction between micro- and macroevolution is not a fundamental one—the difference is simply the time involved.[166] However, in macroevolution, the traits of the entire species may be important. For instance, a large amount of variation among individuals allows a species to rapidly adapt to new habitats, lessening the chance of it going extinct, while a wide geographic range increases the chance of speciation, by making it more likely that part of the population will become isolated. In this sense, microevolution and macroevolution might involve selection at different levels—with microevolution acting on genes and organisms, versus macroevolutionary processes such as species selection acting on entire species and affecting their rates of speciation and extinction.[167][168][169]

A common misconception is that evolution has goals, long-term plans, or an innate tendency for "progress," as expressed in beliefs such as orthogenesis and evolutionism; realistically however, evolution has no long-term goal and does not necessarily produce greater complexity.[170][171][172] Although complex species have evolved, they occur as a side effect of the overall number of organisms increasing and simple forms of life still remain more common in the biosphere.[173] For example, the overwhelming majority of species are microscopic prokaryotes, which form about half the world's biomass despite their small size,[174] and constitute the vast majority of Earth's biodiversity.[175] Simple organisms have therefore been the dominant form of life on Earth throughout its history and continue to be the main form of life up to the present day, with complex life only appearing more diverse because it is more noticeable.[176] Indeed, the evolution of microorganisms is particularly important to modern evolutionary research, since their rapid reproduction allows the study of experimental evolution and the observation of evolution and adaptation in real time.[177][178]

Adaptation

Adaptation is the process that makes organisms better suited to their habitat.[179][180] Also, the term adaptation may refer to a trait that is important for an organism's survival. For example, the adaptation of horses' teeth to the grinding of grass. By using the term adaptation for the evolutionary process and adaptive trait for the product (the bodily part or function), the two senses of the word may be distinguished. Adaptations are produced by natural selection.[181] The following definitions are due to Theodosius Dobzhansky:

- Adaptation is the evolutionary process whereby an organism becomes better able to live in its habitat or habitats.[182]

- Adaptedness is the state of being adapted: the degree to which an organism is able to live and reproduce in a given set of habitats.[183]

- An adaptive trait is an aspect of the developmental pattern of the organism which enables or enhances the probability of that organism surviving and reproducing.[184]

Adaptation may cause either the gain of a new feature, or the loss of an ancestral feature. An example that shows both types of change is bacterial adaptation to antibiotic selection, with genetic changes causing antibiotic resistance by both modifying the target of the drug, or increasing the activity of transporters that pump the drug out of the cell.[185] Other striking examples are the bacteria Escherichia coli evolving the ability to use citric acid as a nutrient in a long-term laboratory experiment,[186] Flavobacterium evolving a novel enzyme that allows these bacteria to grow on the by-products of nylon manufacturing,[187][188] and the soil bacterium Sphingobium evolving an entirely new metabolic pathway that degrades the synthetic pesticide pentachlorophenol.[189][190] An interesting but still controversial idea is that some adaptations might increase the ability of organisms to generate genetic diversity and adapt by natural selection (increasing organisms' evolvability).[191][192][193][194][195]

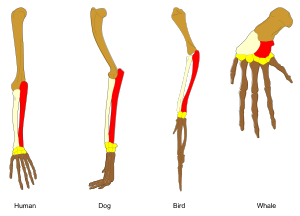

Adaptation occurs through the gradual modification of existing structures. Consequently, structures with similar internal organisation may have different functions in related organisms. This is the result of a single ancestral structure being adapted to function in different ways. The bones within bat wings, for example, are very similar to those in mice feet and primate hands, due to the descent of all these structures from a common mammalian ancestor.[197] However, since all living organisms are related to some extent,[198] even organs that appear to have little or no structural similarity, such as arthropod, squid and vertebrate eyes, or the limbs and wings of arthropods and vertebrates, can depend on a common set of homologous genes that control their assembly and function; this is called deep homology.[199][200]

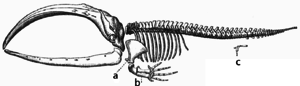

During evolution, some structures may lose their original function and become

However, many traits that appear to be simple adaptations are in fact exaptations: structures originally adapted for one function, but which coincidentally became somewhat useful for some other function in the process.[212] One example is the African lizard Holaspis guentheri, which developed an extremely flat head for hiding in crevices, as can be seen by looking at its near relatives. However, in this species, the head has become so flattened that it assists in gliding from tree to tree—an exaptation.[212] Within cells, molecular machines such as the bacterial flagella[213] and protein sorting machinery[214] evolved by the recruitment of several pre-existing proteins that previously had different functions.[164] Another example is the recruitment of enzymes from glycolysis and xenobiotic metabolism to serve as structural proteins called crystallins within the lenses of organisms' eyes.[215][216]

An area of current investigation in evolutionary developmental biology is the developmental basis of adaptations and exaptations.

Coevolution

Interactions between organisms can produce both conflict and cooperation. When the interaction is between pairs of species, such as a

Cooperation

Not all co-evolved interactions between species involve conflict.[224] Many cases of mutually beneficial interactions have evolved. For instance, an extreme cooperation exists between plants and the mycorrhizal fungi that grow on their roots and aid the plant in absorbing nutrients from the soil.[225] This is a reciprocal relationship as the plants provide the fungi with sugars from photosynthesis. Here, the fungi actually grow inside plant cells, allowing them to exchange nutrients with their hosts, while sending signals that suppress the plant immune system.[226]

Coalitions between organisms of the same species have also evolved. An extreme case is the eusociality found in social insects, such as bees, termites and ants, where sterile insects feed and guard the small number of organisms in a colony that are able to reproduce. On an even smaller scale, the somatic cells that make up the body of an animal limit their reproduction so they can maintain a stable organism, which then supports a small number of the animal's germ cells to produce offspring. Here, somatic cells respond to specific signals that instruct them whether to grow, remain as they are, or die. If cells ignore these signals and multiply inappropriately, their uncontrolled growth causes cancer.[227]

Such cooperation within species may have evolved through the process of kin selection, which is where one organism acts to help raise a relative's offspring.[228] This activity is selected for because if the helping individual contains alleles which promote the helping activity, it is likely that its kin will also contain these alleles and thus those alleles will be passed on.[229] Other processes that may promote cooperation include group selection, where cooperation provides benefits to a group of organisms.[230]

Speciation

Speciation is the process where a species diverges into two or more descendant species.[231]

There are multiple ways to define the concept of "species." The choice of definition is dependent on the particularities of the species concerned.

Speciation has been observed multiple times under both controlled laboratory conditions and in nature.[240] In sexually reproducing organisms, speciation results from reproductive isolation followed by genealogical divergence. There are four primary geographic modes of speciation. The most common in animals is allopatric speciation, which occurs in populations initially isolated geographically, such as by habitat fragmentation or migration. Selection under these conditions can produce very rapid changes in the appearance and behaviour of organisms.[241][242] As selection and drift act independently on populations isolated from the rest of their species, separation may eventually produce organisms that cannot interbreed.[243]

The second mode of speciation is peripatric speciation, which occurs when small populations of organisms become isolated in a new environment. This differs from allopatric speciation in that the isolated populations are numerically much smaller than the parental population. Here, the founder effect causes rapid speciation after an increase in inbreeding increases selection on homozygotes, leading to rapid genetic change.[244]

The third mode is parapatric speciation. This is similar to peripatric speciation in that a small population enters a new habitat, but differs in that there is no physical separation between these two populations. Instead, speciation results from the evolution of mechanisms that reduce gene flow between the two populations.[231] Generally this occurs when there has been a drastic change in the environment within the parental species' habitat. One example is the grass Anthoxanthum odoratum, which can undergo parapatric speciation in response to localised metal pollution from mines.[245] Here, plants evolve that have resistance to high levels of metals in the soil. Selection against interbreeding with the metal-sensitive parental population produced a gradual change in the flowering time of the metal-resistant plants, which eventually produced complete reproductive isolation. Selection against hybrids between the two populations may cause reinforcement, which is the evolution of traits that promote mating within a species, as well as character displacement, which is when two species become more distinct in appearance.[246]

Finally, in sympatric speciation species diverge without geographic isolation or changes in habitat. This form is rare since even a small amount of gene flow may remove genetic differences between parts of a population.[247] Generally, sympatric speciation in animals requires the evolution of both genetic differences and non-random mating, to allow reproductive isolation to evolve.[248]

One type of sympatric speciation involves crossbreeding of two related species to produce a new hybrid species. This is not common in animals as animal hybrids are usually sterile. This is because during meiosis the homologous chromosomes from each parent are from different species and cannot successfully pair. However, it is more common in plants because plants often double their number of chromosomes, to form polyploids.[249] This allows the chromosomes from each parental species to form matching pairs during meiosis, since each parent's chromosomes are represented by a pair already.[250] An example of such a speciation event is when the plant species Arabidopsis thaliana and Arabidopsis arenosa crossbred to give the new species Arabidopsis suecica.[251] This happened about 20,000 years ago,[252] and the speciation process has been repeated in the laboratory, which allows the study of the genetic mechanisms involved in this process.[253] Indeed, chromosome doubling within a species may be a common cause of reproductive isolation, as half the doubled chromosomes will be unmatched when breeding with undoubled organisms.[254]

Speciation events are important in the theory of punctuated equilibrium, which accounts for the pattern in the fossil record of short "bursts" of evolution interspersed with relatively long periods of stasis, where species remain relatively unchanged.[255] In this theory, speciation and rapid evolution are linked, with natural selection and genetic drift acting most strongly on organisms undergoing speciation in novel habitats or small populations. As a result, the periods of stasis in the fossil record correspond to the parental population and the organisms undergoing speciation and rapid evolution are found in small populations or geographically restricted habitats and therefore rarely being preserved as fossils.[168]

Extinction

Extinction is the disappearance of an entire species. Extinction is not an unusual event, as species regularly appear through speciation and disappear through extinction.

The role of extinction in evolution is not very well understood and may depend on which type of extinction is considered.[259] The causes of the continuous "low-level" extinction events, which form the majority of extinctions, may be the result of competition between species for limited resources (the competitive exclusion principle).[59] If one species can out-compete another, this could produce species selection, with the fitter species surviving and the other species being driven to extinction.[127] The intermittent mass extinctions are also important, but instead of acting as a selective force, they drastically reduce diversity in a nonspecific manner and promote bursts of rapid evolution and speciation in survivors.[263]

Evolutionary history of life

million years ago) |

Origin of life

The

More than 99 percent of all species, amounting to over five billion species,[271] that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.[272][273] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million,[274][275] of which about 1.9 million are estimated to have been named[276] and 1.6 million documented in a central database to date,[277] leaving at least 80 percent not yet described.

Highly energetic chemistry is thought to have produced a self-replicating molecule around 4 billion years ago, and half a billion years later the

Common descent

All organisms on Earth are descended from a common ancestor or ancestral gene pool.[198][282] Current species are a stage in the process of evolution, with their diversity the product of a long series of speciation and extinction events.[283] The common descent of organisms was first deduced from four simple facts about organisms: First, they have geographic distributions that cannot be explained by local adaptation. Second, the diversity of life is not a set of completely unique organisms, but organisms that share morphological similarities. Third, vestigial traits with no clear purpose resemble functional ancestral traits and finally, that organisms can be classified using these similarities into a hierarchy of nested groups—similar to a family tree.[284] However, modern research has suggested that, due to horizontal gene transfer, this "tree of life" may be more complicated than a simple branching tree since some genes have spread independently between distantly related species.[285][286]

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record.[287] By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, paleontologists can infer the lineages of those species. However, this approach is most successful for organisms that had hard body parts, such as shells, bones or teeth. Further, as prokaryotes such as bacteria and archaea share a limited set of common morphologies, their fossils do not provide information on their ancestry.

More recently, evidence for common descent has come from the study of biochemical similarities between organisms. For example, all living cells use the same basic set of nucleotides and amino acids.[288] The development of molecular genetics has revealed the record of evolution left in organisms' genomes: dating when species diverged through the molecular clock produced by mutations.[289] For example, these DNA sequence comparisons have revealed that humans and chimpanzees share 98% of their genomes and analysing the few areas where they differ helps shed light on when the common ancestor of these species existed.[290]

Evolution of life

Prokaryotes inhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago.[292][293] No obvious changes in morphology or cellular organisation occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years.[294] The eukaryotic cells emerged between 1.6–2.7 billion years ago. The next major change in cell structure came when bacteria were engulfed by eukaryotic cells, in a cooperative association called endosymbiosis.[295][296] The engulfed bacteria and the host cell then underwent coevolution, with the bacteria evolving into either mitochondria or hydrogenosomes.[297] Another engulfment of cyanobacterial-like organisms led to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants.[298]

The history of life was that of the

Soon after the emergence of these first multicellular organisms, a remarkable amount of biological diversity appeared over approximately 10 million years, in an event called the Cambrian explosion. Here, the majority of types of modern animals appeared in the fossil record, as well as unique lineages that subsequently became extinct.[302] Various triggers for the Cambrian explosion have been proposed, including the accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere from photosynthesis.[303]

About 500 million years ago, plants and fungi colonised the land and were soon followed by

Applications

Concepts and models used in evolutionary biology, such as natural selection, have many applications.[309]

Artificial selection is the intentional selection of traits in a population of organisms. This has been used for thousands of years in the domestication of plants and animals.[310] More recently, such selection has become a vital part of genetic engineering, with selectable markers such as antibiotic resistance genes being used to manipulate DNA. Proteins with valuable properties have evolved by repeated rounds of mutation and selection (for example modified enzymes and new antibodies) in a process called directed evolution.[311]

Understanding the changes that have occurred during an organism's evolution can reveal the genes needed to construct parts of the body, genes which may be involved in human genetic disorders.[312] For example, the Mexican tetra is an albino cavefish that lost its eyesight during evolution. Breeding together different populations of this blind fish produced some offspring with functional eyes, since different mutations had occurred in the isolated populations that had evolved in different caves.[313] This helped identify genes required for vision and pigmentation.[314]

Many human diseases are not static phenomena, but capable of evolution. Viruses, bacteria, fungi and

In computer science, simulations of evolution using evolutionary algorithms and artificial life started in the 1960s and were extended with simulation of artificial selection.[323] Artificial evolution became a widely recognised optimisation method as a result of the work of Ingo Rechenberg in the 1960s. He used evolution strategies to solve complex engineering problems.[324] Genetic algorithms in particular became popular through the writing of John Henry Holland.[325] Practical applications also include automatic evolution of computer programmes.[326] Evolutionary algorithms are now used to solve multi-dimensional problems more efficiently than software produced by human designers and also to optimise the design of systems.[327]

Social and cultural responses

In the 19th century, particularly after the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, the idea that life had evolved was an active source of academic debate centred on the philosophical, social and religious implications of evolution. Today, the modern evolutionary synthesis is accepted by a vast majority of scientists.[59] However, evolution remains a contentious concept for some theists.[329]

While various religions and denominations have reconciled their beliefs with evolution through concepts such as theistic evolution, there are creationists who believe that evolution is contradicted by the creation myths found in their religions and who raise various objections to evolution.[164][330][331] As had been demonstrated by responses to the publication of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in 1844, the most controversial aspect of evolutionary biology is the implication of human evolution that humans share common ancestry with apes and that the mental and moral faculties of humanity have the same types of natural causes as other inherited traits in animals.[332] In some countries, notably the United States, these tensions between science and religion have fuelled the current creation–evolution controversy, a religious conflict focusing on politics and public education.[333] While other scientific fields such as cosmology[334] and Earth science[335] also conflict with literal interpretations of many religious texts, evolutionary biology experiences significantly more opposition from religious literalists.

The teaching of evolution in American secondary school biology classes was uncommon in most of the first half of the 20th century. The

See also

- Argument from poor design

- Biocultural evolution

- Biological classification

- Evidence of common descent

- Evolutionary anthropology

- Evolutionary ecology

- Evolutionary epistemology

- Evolutionary neuroscience

- Evolution of biological complexity

- Evolution of plants

- Timeline of the evolutionary history of life

- Unintelligent design

- Universal Darwinism

References

- ^ Hall & Hallgrímsson 2008, pp. 4–6

- ^ "Evolution Resources". National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03.

- ^ Hall & Hallgrímsson 2008, pp. 3–5

- ^ Panno 2005, pp. xv-16

- ^ doi:10.1038/ngeo2025. Retrieved 9 Dec 2013.).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "NG-20131208" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page - ^ AP News. Retrieved 15 November 2013. Cite error: The named reference "AP-20131113" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Pearlman, Jonathan (November 13, 2013). "'Oldest signs of life on Earth found'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ^ ).

- ^ Futuyma 2004, p. 33

- S2CID 4422345.

- PMID 10710791.

- PMID 18613974.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-06.

- ^ Darwin 1859, Chapter XIV

- PMID 24325256.

Evolutionary processes are generally thought of as processes by which these changes occur. Four such processes are widely recognized: natural selection (in the broad sense, to include sexual selection), genetic drift, mutation, and migration (Fisher 1930; Haldane 1932). The latter two generate variation; the first two sort it.

- ^ Provine 1988, pp. 49–79

- ^ NAS 2008, pp. R11–R12 Archived 2014-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ayala & Avise 2014[page needed]

- ^ NAS 2008, p. 17 Archived 2015-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Moore, Decker & Cotner 2010, p. 454

- OCLC 43422991. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-01-31. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ^ Darwin 1909, p. 53

- ^ Kirk, Raven & Schofield 1983, pp. 100–142, 280–321

- )

- ISSN 1477-3643. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- S2CID 170831302.

- S2CID 170328394.

- ^ Mason 1962, pp. 43–44

- ^ Mayr 1982, pp. 256–257

- ^ Waggoner, Ben (July 7, 2000). "Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778)". Evolution (Online exhibit). Berkeley, CA: University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-11.

- ^ Bowler 2003, pp. 73–75

- ^ "Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802)". Evolution (Online exhibit). Berkeley, CA: University of California Museum of Paleontology. October 4, 1995. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ Lamarck 1809

- ^ a b Nardon & Grenier 1991, p. 162

- ^ a b c Gould 2002 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGould2002 (help)[page needed]

- from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Magner 2002[page needed]

- S2CID 15879804.

- ^ Burkhardt & Smith 1991

- "Darwin, C. R. to Lubbock, John". Darwin Correspondence Project. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 2014-12-15. Retrieved 2014-12-01. Letter 2532, November 22, 1859.

- S2CID 12289290.

- ^ Dawkins 1990[page needed]

- PMID 19528655.

- ^ Mayr 2002, p. 165

- ^ Bowler 2003, pp. 145–146

- S2CID 83528114.

- from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archivedfrom the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- S2CID 19919317.

- PMID 1887835.

- ^ Wright 1984, p. 480

- ^ Provine 1971

- S2CID 20200394.

- ^ Quammen 2006[page needed]

- ^ Bowler 1989[page needed]

- (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.

- ^ Hennig 1999, p. 280

- ^ Wiley & Lieberman 2011[page needed]

- (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-23.

- ^ S2CID 10731711.

- ^ Cracraft & Bybee 2005[page needed]

- ISSN 0027-8424. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-29.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of June 2022 (link - S2CID 8837202.

- ISBN 978-0262513678. Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2015.

- PMID 15262401.

- ^ S2CID 4420674.

- S2CID 690431.

- PMID 8796918.

- ^ a b Futuyma 2005[page needed]

- PMID 18852697.

- ^ S2CID 24301815.

- S2CID 7233550.

- S2CID 15763479.

- ^ Jablonka & Lamb 2005[page needed]

- S2CID 12561900.

- S2CID 22997236.

- PMID 10943381. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- S2CID 37774648. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-05-11.

- PMID 9533122.

- ^ a b Ewens 2004[page needed]

- PMID 9533123.

- Butlin, Roger K.; Tregenza, Tom (December 29, 2000). "Correction for Butlin and Tregenza, Levels of genetic polymorphism: marker loci versus quantitative traits". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 355 (1404). London: Royal Society: 1865. ISSN 0962-8436.

Some of the values in table 1 on p. 193 were given incorrectly. The errors do not affect the conclusions drawn in the paper. The corrected table is reproduced below.

- Butlin, Roger K.; Tregenza, Tom (December 29, 2000). "Correction for Butlin and Tregenza, Levels of genetic polymorphism: marker loci versus quantitative traits". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 355 (1404). London: Royal Society: 1865.

- S2CID 7257193.

- PMID 17409186.

- PMID 19597530.

- ^ Carroll, Grenier & Weatherbee 2005[page needed]

- PMID 12083509.

- S2CID 12851209.

- from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- PMID 15252449.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 18711447.

- from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- PMID 15954844.

- S2CID 33999892.

- PMID 19141283.

- S2CID 205552778.

- PMID 6297377.

- S2CID 14739487.

- PMID 12766942.

- S2CID 4397491.

- ^ Maynard Smith 1978[page needed]

- ^ a b Ridley 1993[page needed]

- ISSN 0093-4755. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2014-12-24.

- PMID 2185476.

- ^ Birdsell & Wills 2003, pp. 113–117

- ^ PMID 15140081.

- PMID 14616063.

- PMID 16942901.

- PMID 12386340.

- PMID 1822285.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 11862013.

- PMID 10438861.

- S2CID 4349149.

- ^ S2CID 1670587.

- ^ PMID 19546856.

- S2CID 4185793.

- PMID 28556011.

- S2CID 30703407.

- PMID 18814933.

- S2CID 40851098.

- PMID 11470913.

- PMID 17248980.

- (PDF) from the original on 2013-03-09.

- PMID 12079655.

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- S2CID 4417867.

- ^ Odum 1971, p. 8

- ^ Okasha 2006

- ^ PMID 9533127.

- PMID 9122151.

- ^ Maynard Smith 1998, pp. 203–211, discussion 211–217

- PMID 1334911.

- PMID 10518549.

- PMID 17494740.

- from the original on 2014-08-23.

- PMID 10669421.

- S2CID 5314242.

- S2CID 4503181.

- PMID 20300655.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - (PDF) from the original on June 12, 2007.

- ^ West-Eberhard 2003, pp. 140

- ^ Pocheville, Arnaud; Danchin, Etienne (January 1, 2017). "Chapter 3: Genetic assimilation and the paradox of blind variation". In Huneman, Philippe; Walsh, Denis (eds.). Challenging the Modern Synthesis. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017.

- PMID 19625453.

- S2CID 26956345.

- S2CID 84059440.

- PMID 17306543.

- PMID 17206583.

- ^ S2CID 17619958.

- PMID 2687093.

- S2CID 14914998.

- PMID 16120807.

- Nei, Masatoshi (May 2006). "Selectionism and Neutralism in Molecular Evolution". Molecular Biology and Evolution (Erratum). 23 (5). Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution: 1095. ISSN 0737-4038.

- Nei, Masatoshi (May 2006). "Selectionism and Neutralism in Molecular Evolution". Molecular Biology and Evolution (Erratum). 23 (5). Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution: 1095.

- from the original on 2014-12-16.

- PMID 2687096.

- PMID 8760341.

- S2CID 2081042.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 221735887.

- PMID 21625002.

- (PDF) from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2014-12-18.

- ^ S2CID 205484393.

- PMID 20508143.

- PMID 10677316.

- PMID 11127900.

- ^ Wright, Sewall (1932). "The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding and selection in evolution". Proceedings of the VI International Congress of Genetrics. 1: 356–366. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-12-18.

- PMID 28568586.

- PMID 27609891.

- ^ PMID 17494747.

- S2CID 24485535.

- S2CID 17289010.

- ^ Gould 2002, pp. 657–658. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGould2002 (help)

- ^ PMID 8041695.

- S2CID 53451360.

- from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- ^ Isaak, Mark, ed. (July 22, 2003). "Claim CB932: Evolution of degenerate forms". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- ^ Lane 1996, p. 61

- S2CID 4319886.

- PMID 9618454.

- ^ PMID 15590780.

- S2CID 12289639.

- S2CID 205216404.

- S2CID 209727.

- ^ Mayr 1982, p. 483: "Adaptation... could no longer be considered a static condition, a product of a creative past and became instead a continuing dynamic process."

- ^ The sixth edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Science (2010) defines adaptation as "Any change in the structure or functioning of successive generations of a population that makes it better suited to its environment."

- S2CID 17772950.

- ^ Dobzhansky 1968, pp. 1–34

- ^ Dobzhansky 1970, pp. 4–6, 79–82, 84–87

- JSTOR 2406099.

- S2CID 22593331.

- PMID 18524956.

- S2CID 4364682.

- PMID 6585807.

- PMID 10838562.

- S2CID 8174462.

- JSTOR 3212376.

- ^ Altenberg 1995, pp. 205–259

- S2CID 30954684.

- PMID 19917766.

- S2CID 11560256.

- ^ S2CID 8448387.

- S2CID 198156135.

- ^ PMID 10607605.

- S2CID 22142786.

- S2CID 205216390.

- ^ ISSN 1545-2069.

- PMID 15261647.

- PMID 15653557.

- S2CID 12494187.

- (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-23. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- PMID 12733778. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Coyne 2009, p. 62

- ^ Darwin 1872, pp. 101, 103

- ^ Gray 2007, p. 66

- ^ Coyne 2009, pp. 85–86

- ^ Stevens 1982, p. 87

- ^ a b Gould 2002, pp. 1235–1236. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGould2002 (help)

- (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-26. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- PMID 19717453.

- ^ Piatigorsky et al. 1994, pp. 241–250

- PMID 8236445.

- S2CID 1651351.

- from the original on 2014-11-28.

- Love, Alan C. (March 2003). "Evolutionary Morphology, Innovation and the Synthesis of Evolutionary and Developmental Biology". Biology and Philosophy. 18 (2). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers: 309–345. S2CID 82307503.

- Love, Alan C. (March 2003). "Evolutionary Morphology, Innovation and the Synthesis of Evolutionary and Developmental Biology". Biology and Philosophy. 18 (2). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers: 309–345.

- S2CID 25886311.

- S2CID 15733491.

- S2CID 2513041.

- S2CID 36705246.

- S2CID 8816337.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link- Brodie, Edmund D., Jr.; Ridenhour, Benjamin J.; Brodie, Edmund D., III (October 2002). "The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts". Evolution. 56 (10). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution: 2067–2082. S2CID 8251443.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Carroll, Sean B. (December 21, 2009). "Whatever Doesn't Kill Some Animals Can Make Them Deadly". The New York Times. New York. from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- Brodie, Edmund D., Jr.; Ridenhour, Benjamin J.; Brodie, Edmund D., III (October 2002). "The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts". Evolution. 56 (10). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution: 2067–2082.

- S2CID 4828678.

- PMID 17158317.

- PMID 16713732.

- S2CID 20082902.

- PMID 11173079.

- PMID 17517608.

- PMID 7466396.

- PMID 16157878.

- ^ S2CID 198158082.

- ^ PMID 15851674.

- ^ S2CID 224829314.

- ^ Mayr 1942, p. 120

- S2CID 15763831.

- PMID 1107543.

- PMID 15618301.

- PMID 11700276.

- S2CID 11657663.

- PMID 28568007.

- Jiggins, Chris D.; Bridle, Jon R. (March 2004). "Speciation in the apple maggot fly: a blend of vintages?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 19 (3). Cambridge, MA: Cell Press: 111–114. PMID 16701238.

- Boxhorn, Joseph (September 1, 1995). "Observed Instances of Speciation". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Weinberg, James R.; Starczak, Victoria R.; Jörg, Daniele (August 1992). "Evidence for Rapid Speciation Following a Founder Event in the Laboratory". Evolution. 46 (4). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution: 1214–1220. PMID 28564398.

- Jiggins, Chris D.; Bridle, Jon R. (March 2004). "Speciation in the apple maggot fly: a blend of vintages?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 19 (3). Cambridge, MA: Cell Press: 111–114.

- PMID 18344323.

- S2CID 4242248.

- S2CID 4417281.

- from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- S2CID 10808041.

- S2CID 867216.

- Barluenga, Marta; Stölting, Kai N.; Salzburger, Walter; et al. (February 9, 2006). "Sympatric speciation in Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fish". Nature. 439 (7077). London: Nature Publishing Group: 719–23. S2CID 3165729.

- Barluenga, Marta; Stölting, Kai N.; Salzburger, Walter; et al. (February 9, 2006). "Sympatric speciation in Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fish". Nature. 439 (7077). London: Nature Publishing Group: 719–23.

- PMID 16242727.

- PMID 19667210.

- S2CID 1584282.

- PMID 16549398.

- S2CID 29281998.

- PMID 18006296.

- PMID 18006297.

- ^ Eldredge & Gould 1972, pp. 82–115

- PMID 7701342.

- PMID 11542058.

- PMID 18695213.

- ^ PMID 8041694.

- PMID 11344295.

- PMID 16829570.

- Barnosky, Anthony D.; Koch, Paul L.; Feranec, Robert S.; et al. (October 1, 2004). "Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents". Science. 306 (5693). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 70–75. S2CID 36156087.

- Barnosky, Anthony D.; Koch, Paul L.; Feranec, Robert S.; et al. (October 1, 2004). "Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents". Science. 306 (5693). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 70–75.

- PMID 16553315.

- PMID 11344284.

- ^ "Age of the Earth". United States Geological Survey. July 9, 2007. Archived from the original on December 23, 2005. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- ^ Dalrymple 2001, pp. 205–221

- ISSN 0012-821X.

- ISSN 0301-9268.

- ^ Raven & Johnson 2002, p. 68

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth (October 19, 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Excite. Yonkers, NY: Mindspark Interactive Network. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- (PDF) from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ^ McKinney 1997, p. 110

- ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6. Archivedfrom the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- PMID 21886479.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ Miller & Spoolman 2012, p. 62

- ISBN 978-0-642-56860-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ^ "Catalogue of Life: 2016 Annual Checklist". 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-12. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- PMID 10710791. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- PMID 15906258. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2015-08-24.

- S2CID 4331004.

- PMID 11742692.

- S2CID 4422345.

- PMID 15936656.

- ^ Darwin 1859, p. 1

- PMID 17261804.

- PMID 15965028.

- PMID 10381868.

- S2CID 103653.

- PMID 12175808.

- PMID 16339373.

- (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ PMID 16754610.

- PMID 16754604.

- Altermann, Wladyslaw; Kazmierczak, Józef (November 2003). "Archean microfossils: a reappraisal of early life on Earth". Research in Microbiology. 154 (9). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier for the PMID 14596897.

- Altermann, Wladyslaw; Kazmierczak, Józef (November 2003). "Archean microfossils: a reappraisal of early life on Earth". Research in Microbiology. 154 (9). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier for the

- PMID 8041691.

- PMID 17187354.

- S2CID 19424594.

- PMID 16109488.

- PMID 10690412.

- McFadden, Geoffrey Ian (December 1, 1999). "Endosymbiosis and evolution of the plant cell". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2 (6). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 513–519. PMID 10607659.

- McFadden, Geoffrey Ian (December 1, 1999). "Endosymbiosis and evolution of the plant cell". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2 (6). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 513–519.

- (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2016.

- PMID 11700279.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (January 7, 2016). "Genetic Flip Helped Organisms Go From One Cell to Many". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- from the original on March 1, 2015. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- S2CID 21879320.

- Valentine, James W.; Jablonski, David (2003). "Morphological and developmental macroevolution: a paleontological perspective". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 47 (7–8). Bilbao, Spain: University of the Basque Country Press: 517–522. from the original on 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- PMID 14615186.

- S2CID 9356614.

- ISSN 1096-3642.

- S2CID 4334424.

- S2CID 205066360.

- ISSN 1545-2069.

- S2CID 278993.

- PMID 18573077.

- S2CID 41648315.

- S2CID 16967690.

- PMID 19119422.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - S2CID 8040576.

- PMID 22698669.

- PMID 17184282.

- PMID 18020711.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ISSN 0043-1737.

- PMID 23517688.

- PMID 22761587.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 19355786.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - S2CID 4211563.

- ^ Rechenberg 1973

- ^ Holland 1975

- ^ Koza 1992

- S2CID 34259612.

- ^ Browne 2003, pp. 376–379

- ^ For an overview of the philosophical, religious and cosmological controversies, see:

For the scientific and social reception of evolution in the 19th and early 20th centuries, see:

- Johnston, Ian C. (1999). "Section Three: The Origins of Evolutionary Theory". . . . And Still We Evolve: A Handbook for the Early History of Modern Science (3rd revised ed.). Nanaimo, BC: Liberal Studies Department, Malaspina University-College. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

- Bowler 2003

- PMID 17011142.

- (PDF) from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- S2CID 206515329. Archived from the original(PDF) on November 10, 2014.

- ^ Bowler 2003

- S2CID 152990938.

- S2CID 10794058.

- S2CID 4319774.

- S2CID 86665329.

Bibliography

- Altenberg, Lee (1995). "Genome growth and the evolution of the genotype-phenotype map". In Banzhaf, Wolfgang; Eeckman, Frank H. (eds.). Evolution and Biocomputation: Computational Models of Evolution. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 899. Berlin; New York: OCLC 32049812.

- OCLC 854285705.

- Birdsell, John A.; OCLC 751583918.

- OCLC 19322402.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd completely rev. and expanded ed.). Berkeley, CA: OCLC 49824702.

- OCLC 52327000.

- OCLC 185662993.

- OCLC 53972564.

- OCLC 233549529.

- Cracraft, Joel; Bybee, Rodger W., eds. (2005). Evolutionary Science and Society: Educating a New Generation (PDF). Colorado Springs, CO: OCLC 64228003. Retrieved 2014-12-06. "Revised Proceedings of the BSCS, AIBS Symposium November 2004, Chicago, Illinois"

- S2CID 130092094.

- OCLC 741260650. The book is available from The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- Darwin, Charles (1872). OCLC 1102785.

- OCLC 1184581. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- OCLC 60143870.

- OCLC 31867409.

- OCLC 24875357.

- Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1970). Genetics of the Evolutionary Process. New York: OCLC 97663.

- OCLC 572084.

- Eldredge, Niles (1985). Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. New York: OCLC 11443805.

- Eldredge, Niles (1985). Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. New York:

- OCLC 53231891.

- OCLC 61342697. "Proceedings of a symposium held at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, 2002."

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (2005). Evolution. Sunderland, MA: OCLC 57311264.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). OCLC 47869352.

- OCLC 76872504.

- OCLC 85814089.

- OCLC 722701473.

- OCLC 1531617.

- OCLC 61896061.

- Kampourakis, Kostas (2014). Understanding Evolution. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 855585457.

- OCLC 9081712.

- OCLC 26263956.

- . Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Lane, David H. (1996). The Phenomenon of Teilhard: Prophet for a New Age (1st ed.). Macon, GA: OCLC 34710780.

- Magner, Lois N. (2002). A History of the Life Sciences (3rd rev. and expanded ed.). New York: OCLC 50410202.

- Mason, Stephen F. (1962). A History of the Sciences. Collier Books. Science Library, CS9 (New rev. ed.). New York: OCLC 568032626.

- OCLC 3413793.

- Maynard Smith, John (1998). "The Units of Selection". In Bock, Gregory R.; Goode, Jamie A. (eds.). The Limits of Reductionism in Biology. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 213. Chichester, England: PMID 9653725. "Papers from the Symposium on the Limits of Reductionism in Biology, held at the Novartis Foundation, London, May 13–15, 1997."

- OCLC 766053.

- Mayr, Ernst (1982). OCLC 7875904.

- Mayr, Ernst (2002) [Originally published 2001; New York: OCLC 248107061.

- McKinney, Michael L. (1997). "How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view". In Kunin, William E.; Gaston, Kevin J. (eds.). The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences (1st ed.). London; New York: OCLC 36442106.

- Miller, G. Tyler; Spoolman, Scott E. (2012). Environmental Science (14th ed.). Belmont, CA: OCLC 741539226. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

- Moore, Randy; Decker, Mark; Cotner, Sehoya (2010). Chronology of the Evolution-Creationism Controversy. Santa Barbara, CA: OCLC 422757410.

- Nardon, Paul; Grenier, Anne-Marie (1991). "Serial Endosymbiosis Theory and Weevil Evolution: The Role of Symbiosis". In OCLC 22597587. "Based on a conference held in Bellagio, Italy, June 25–30, 1989"

- OCLC 123539346. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- OCLC 154846.

- Okasha, Samir (2006). Evolution and the Levels of Selection. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 70985413.

- Panno, Joseph (2005). The Cell: Evolution of the First Organism. Facts on File science library. New York: OCLC 53901436.

- Piatigorsky, Joram; Kantorow, Marc; Gopal-Srivastava, Rashmi; Tomarev, Stanislav I. (1994). "Recruitment of enzymes and stress proteins as lens crystallins". In Jansson, Bengt; Jörnvall, Hans; Rydberg, Ulf; et al. (eds.). Toward a Molecular Basis of Alcohol Use and Abuse. Experientia. Vol. 71. Basel; Boston: PMID 8032155.

- OCLC 46660910.

- Provine, William B. (1988). "Progress in Evolution and Meaning in Life". In Nitecki, Matthew H. (ed.). Evolutionary Progress. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 18380658. "This book is the result of the Spring Systematics Symposium held in May, 1987, at the Field Museum in Chicago"

- OCLC 65400177.

- OCLC 45806501.

- OCLC 2126030.

- OCLC 9020616.

- OCLC 636657988.

- OCLC 10458367.

- OCLC 48398911.

- OCLC 741259265.

- OCLC 246124737.

Further reading

Introductory reading