User:Seans Potato Business/DNA

Reference Check

- 1ab, 2 not checked - no access

- 3 ERROR - based on abstract: source gives 22-26 angstrom (2.2 - 2.6 nm) width

- 4 not checked - no access

- 5ab checked OK

- a quote="The novel feature of the structure is the manner in which the two cheins are held together by the purine and pyrimidine beses. The planes of the bases are perpendicular to the fiber axis. They are joined together in pairs, a single base from one chain being hydrogen-bonded to a single base from the other chain"

- b quote not applicable

- 6 not checked - no access

- 7ab ERROR

- 7a ERROR - does not seem a suitable source: supporting information may or may not be inferred but suggest replacement with a source that provides it explicitly

- 7b ERROR - does not provide structural information of nucleotides not explicitly state that A+G are purines while C+T are pyramidines

- 8ab not checked - no access

- 9 not checked - no access

- 10, 11 in progress

- 12 not checked - no access

- 13 ERROR - based on pubmed abstract: quote="Cro, repressor, and CAP use alpha-helices for many of the contacts between side chains and bases in the major groove" - suggest this is insufficient to make the assertion that "proteins like transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contacts to the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove" - suggest further scrutiny of entire text.

- 14 checked ok - quote="The situation in nucleic acid systems is somewhat different: from our present model, the analysis of the different contributions seen in Table 2 shows that the components base stacking, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals terms are the major partners; the relative contributions are 33.4% base stacking, 30.3% van der Waaks, 18.2% hydrogen bonding, 12.1% hydrophobic, and 6.1% electrostatic"

Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA is a nucleic acid molecule that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all living organisms. The main role of DNA is the long-term storage of information and it is often compared to a set of blueprints, since DNA contains the instructions needed to construct other components of cells, such as proteins and RNA molecules. The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in regulating the use of this genetic information.

Chemically, DNA is a long

Within cells, DNA is organized into structures called

Physical and chemical properties

DNA is a long

In living organisms, DNA does not usually exist as a single molecule, but instead as a tightly-associated pair of molecules.[5][6] These two long strands entwine like vines, in the shape of a double helix. The nucleotide repeats contain both the segment of the backbone of the molecule, which holds the chain together, and a base, which interacts with the other DNA strand in the helix. In general, a base linked to a sugar is called a nucleoside and a base linked to a sugar and one or more phosphate groups is called a nucleotide. If multiple nucleotides are linked together, as in DNA, this polymer is referred to as a polynucleotide.[7]

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating phosphate and sugar residues.[8] The sugar in DNA is 2-deoxyribose, which is a pentose (five carbon) sugar. The sugars are joined together by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms of adjacent sugar rings. These asymmetric bonds mean a strand of DNA has a direction. In a double helix the direction of the nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other strand. This arrangement of DNA strands is called antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of a strand of DNA bases are referred to as the 5′ (five prime) and 3′ (three prime) ends. One of the major differences between DNA and RNA is the sugar, with 2-deoxyribose being replaced by the alternative pentose sugar ribose in RNA.[6]

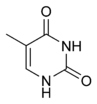

The DNA double helix is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the bases attached to the two strands. The four bases found in DNA are adenine (abbreviated A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). These four bases are shown below and are attached to the sugar/phosphate to form the complete nucleotide, as shown for adenosine monophosphate.

These bases are classified into two types; adenine and guanine are fused five- and six-membered

The double helix is a right-handed spiral. As the DNA strands wind around each other, they leave gaps between each set of phosphate backbones, revealing the sides of the bases inside (see animation). There are two of these grooves twisting around the surface of the double helix: one groove, the major groove, is 22 Å wide and the other, the minor groove, is 12 Å wide.[12] The narrowness of the minor groove means that the edges of the bases are more accessible in the major groove. As a result, proteins like transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contacts to the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.[13]

|

|

Base pairing

Each type of base on one strand forms a bond with just one type of base on the other strand. This is called complementary

The two types of base pairs form different numbers of hydrogen bonds, AT forming two hydrogen bonds, and GC forming three hydrogen bonds (see figures, left). The GC base pair is therefore stronger than the AT base pair. As a result, it is both the percentage of GC base pairs and the overall length of a DNA double helix that determine the strength of the association between the two strands of DNA. Long DNA helices with a high GC content have stronger-interacting strands, while short helices with high AT content have weaker-interacting strands.[16] Parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the TATAAT Pribnow box in bacterial promoters, tend to have sequences with a high AT content, making the strands easier to pull apart.[17] In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be measured by finding the temperature required to break the hydrogen bonds, their melting temperature (also called Tm value). When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules. These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single common shape, but some conformations are more stable than others.[18]

Sense and antisense

A DNA sequence is called "sense" if its sequence is the same as that of a messenger RNA (mRNA) copy that is translated into protein. The sequence on the opposite strand is complementary to the sense sequence and is therefore called the "antisense" sequence. Since RNA polymerases work by making a complementary copy of their templates, it is this antisense strand that is the template for producing the sense mRNA. Both sense and antisense sequences can exist on different parts of the same strand of DNA (i.e. both strands contain both sense and antisense sequences). In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, antisense RNA sequences are produced, but the functions of these RNAs are not entirely clear.[19] One proposal is that antisense RNAs are involved in regulating gene expression through RNA-RNA base pairing.[20]

A few DNA sequences in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and more in plasmids and viruses, blur the distinction made above between sense and antisense strands by having overlapping genes.[21] In these cases, some DNA sequences do double duty, encoding one protein when read 5′ to 3′ along one strand, and a second protein when read in the opposite direction (still 5′ to 3′) along the other strand. In bacteria, this overlap may be involved in the regulation of gene transcription,[22] while in viruses, overlapping genes increase the amount of information that can be encoded within the small viral genome.[23] Another way of reducing genome size is seen in some viruses that contain linear or circular single-stranded DNA as their genetic material.[24][25]

Supercoiling

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called

Alternative double-helical structures

DNA exists in several possible conformations. The conformations so far identified are: A-DNA, B-DNA, C-DNA, D-DNA,[29] E-DNA,[30] H-DNA,[31] L-DNA,[29] P-DNA,[32] and Z-DNA.[8][33] However, only A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA have been observed in naturally occurring biological systems. Which conformation DNA adopts depends on the sequence of the DNA, the amount and direction of supercoiling, chemical modifications of the bases and also solution conditions, such as the concentration of metal ions and polyamines.[34] Of these three conformations, the "B" form described above is most common under the conditions found in cells.[35] The two alternative double-helical forms of DNA differ in their geometry and dimensions.

The A form is a wider right-handed spiral, with a shallow and wide minor groove and a narrower and deeper major groove. The A form occurs under non-physiological conditions in dehydrated samples of DNA, while in the cell it may be produced in hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, as well as in enzyme-DNA complexes.[36][37] Segments of DNA where the bases have been chemically-modified by methylation may undergo a larger change in conformation and adopt the Z form. Here, the strands turn about the helical axis in a left-handed spiral, the opposite of the more common B form.[38] These unusual structures can be recognised by specific Z-DNA binding proteins and may be involved in the regulation of transcription.[39]

Quadruplex structures

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called telomeres. The main function of these regions is to allow the cell to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase, as the enzymes that normally replicate DNA cannot copy the extreme 3′ ends of chromosomes.[41] As a result, if a chromosome lacked telomeres it would become shorter each time it was replicated. These specialized chromosome caps also help protect the DNA ends from exonucleases and stop the DNA repair systems in the cell from treating them as damage to be corrected.[42] In human cells, telomeres are usually lengths of single-stranded DNA containing several thousand repeats of a simple TTAGGG sequence.[43]

These guanine-rich sequences may stabilize chromosome ends by forming very unusual structures of stacked sets of four-base units, rather than the usual base pairs found in other DNA molecules. Here, four guanine bases form a flat plate and these flat four-base units then stack on top of each other, to form a stable quadruplex structure.[44] These structures are stabilized by hydrogen bonding between the edges of the bases and chelation of a metal ion in the centre of each four-base unit. The structure shown to the left is a top view of the quadruplex formed by a DNA sequence found in human telomere repeats. The single DNA strand forms a loop, with the sets of four bases stacking in a central quadruplex three plates deep. In the space at the centre of the stacked bases are three chelated potassium ions.[45] Other structures can also be formed, with the central set of four bases coming from either a single strand folded around the bases, or several different parallel strands, each contributing one base to the central structure.

In addition to these stacked structures, telomeres also form large loop structures called telomere loops, or T-loops. Here, the single-stranded DNA curls around in a long circle stabilized by telomere-binding proteins.[46] At the very end of the T-loop, the single-stranded telomere DNA is held onto a region of double-stranded DNA by the telomere strand disrupting the double-helical DNA and base pairing to one of the two strands. This triple-stranded structure is called a displacement loop or D-loop.[44]

Chemical modifications

|

|

|

| cytosine | 5-methylcytosine | thymine |

Base modifications

The expression of genes is influenced by the

DNA damage

DNA can be damaged by many different sorts of

Many mutagens

Overview of biological functions

DNA usually occurs as linear

Genome structure

Genomic DNA is located in the cell nucleus of eukaryotes, as well as small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.[63] The genetic information in a genome is held within genes. A gene is a unit of heredity and is a region of DNA that influences a particular characteristic in an organism. Genes contain an open reading frame that can be transcribed, as well as regulatory sequences such as promoters and enhancers, which control the expression of the open reading frame.

In many

Some non-coding DNA sequences play structural roles in chromosomes. Telomeres and centromeres typically contain few genes, but are important for the function and stability of chromosomes.[42][67] An abundant form of non-coding DNA in humans are pseudogenes, which are copies of genes that have been disabled by mutation.[68] These sequences are usually just molecular fossils, although they can occasionally serve as raw genetic material for the creation of new genes through the process of gene duplication and divergence.[69]

Transcription and translation

A gene is a sequence of DNA that contains genetic information and can influence the

In transcription, the codons of a gene are copied into messenger RNA by RNA polymerase. This RNA copy is then decoded by a ribosome that reads the RNA sequence by base-pairing the messenger RNA to transfer RNA, which carries amino acids. Since there are 4 bases in 3-letter combinations, there are 64 possible codons ( combinations). These encode the twenty

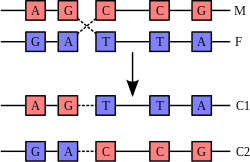

Replication

Cell division is essential for an organism to grow, but when a cell divides it must replicate the DNA in its genome so that the two daughter cells have the same genetic information as their parent. The double-stranded structure of DNA provides a simple mechanism for DNA replication. Here, the two strands are separated and then each strand's complementary DNA sequence is recreated by an enzyme called DNA polymerase. This enzyme makes the complementary strand by finding the correct base through complementary base pairing, and bonding it onto the original strand. As DNA polymerases can only extend a DNA strand in a 5′ to 3′ direction, different mechanisms are used to copy the antiparallel strands of the double helix.[70] In this way, the base on the old strand dictates which base appears on the new strand, and the cell ends up with a perfect copy of its DNA.

Interactions with proteins

All the functions of DNA depend on interactions with proteins. These protein interactions can be non-specific, or the protein can bind specifically to a single DNA sequence. Enzymes can also bind to DNA and of these, the polymerases that copy the DNA base sequence in transcription and DNA replication are particularly important.

DNA-binding proteins

|

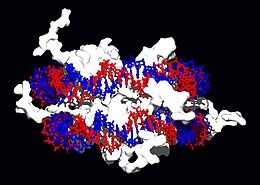

Structural proteins that bind DNA are well-understood examples of non-specific DNA-protein interactions. Within chromosomes, DNA is held in complexes with structural proteins. These proteins organize the DNA into a compact structure called

A distinct group of DNA-binding proteins are the single-stranded-DNA-binding proteins that specifically bind single-stranded DNA. In humans, replication protein A is the best-characterised member of this family and is essential for most processes where the double helix is separated, including DNA replication, recombination and DNA repair.

In contrast, other proteins have evolved to specifically bind particular DNA sequences. The most intensively studied of these are the various classes of transcription factors, which are proteins that regulate transcription. Each one of these proteins bind to one particular set of DNA sequences and thereby activates or inhibits the transcription of genes with these sequences close to their promoters. The transcription factors do this in two ways. Firstly, they can bind the RNA polymerase responsible for transcription, either directly or through other mediator proteins; this locates the polymerase at the promoter and allows it to begin transcription.[80] Alternatively, transcription factors can bind enzymes that modify the histones at the promoter; this will change the accessibility of the DNA template to the polymerase.[81]

As these DNA targets can occur throughout an organism's genome, changes in the activity of one type of transcription factor can affect thousands of genes.[82] Consequently, these proteins are often the targets of the signal transduction processes that mediate responses to environmental changes or cellular differentiation and development. The specificity of these transcription factors' interactions with DNA come from the proteins making multiple contacts to the edges of the DNA bases, allowing them to "read" the DNA sequence. Most of these base-interactions are made in the major groove, where the bases are most accessible.[83]

DNA-modifying enzymes

Nucleases and ligases

Nucleases are

Enzymes called

Topoisomerases and helicases

Topoisomerases are enzymes with both nuclease and ligase activity. These proteins change the amount of supercoiling in DNA. Some of these enzyme work by cutting the DNA helix and allowing one section to rotate, thereby reducing its level of supercoiling; the enzyme then seals the DNA break.[27] Other types of these enzymes are capable of cutting one DNA helix and then passing a second strand of DNA through this break, before rejoining the helix.[87] Topoisomerases are required for many processes involving DNA, such as DNA replication and transcription.[28]

Helicases are proteins that are a type of molecular motor. They use the chemical energy in nucleoside triphosphates, predominantly ATP, to break hydrogen bonds between bases and unwind the DNA double helix into single strands.[88] These enzymes are essential for most processes where enzymes need to access the DNA bases.

Polymerases

Polymerases are enzymes that synthesise polynucleotide chains from

In DNA replication, a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase makes a DNA copy of a DNA sequence. Accuracy is vital in this process, so many of these polymerases have a proofreading activity. Here, the polymerase recognizes the occasional mistakes in the synthesis reaction by the lack of base pairing between the mismatched nucleotides. If a mismatch is detected, a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity is activated and the incorrect base removed.[90] In most organisms DNA polymerases function in a large complex called the replisome that contains multiple accessory subunits, such as the DNA clamp or helicases.[91]

RNA-dependent DNA polymerases are a specialised class of polymerases that copy the sequence of an RNA strand into DNA. They include reverse transcriptase, which is a viral enzyme involved in the infection of cells by retroviruses, and telomerase, which is required for the replication of telomeres.[92][41] Telomerase is an unusual polymerase because it contains its own RNA template as part of its structure.[42]

Transcription is carried out by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase that copies the sequence of a DNA strand into RNA. To begin transcribing a gene, the RNA polymerase binds to a sequence of DNA called a promoter and separates the DNA strands. It then copies the gene sequence into a messenger RNA transcript until it reaches a region of DNA called the terminator, where it halts and detaches from the DNA. As with human DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, RNA polymerase II, the enzyme that transcribes most of the genes in the human genome, operates as part of a large protein complex with multiple regulatory and accessory subunits.[93]

Genetic recombination

|

|

A DNA helix does not usually interact with other segments of DNA, and in human cells the different chromosomes even occupy separate areas in the nucleus called "chromosome territories".[95] This physical separation of different chromosomes is important for the ability of DNA to function as a stable repository for information, as one of the few times chromosomes interact is during chromosomal crossover when they recombine. Chromosomal crossover is when two DNA helices break, swap a section and then rejoin.

Recombination allows chromosomes to exchange genetic information and produces new combinations of genes, which increases the efficiency of natural selection and can be important in the rapid evolution of new proteins.[96] Genetic recombination can also be involved in DNA repair, particularly in the cell's response to double-strand breaks.[97]

The most common form of chromosomal crossover is

Evolution of DNA-based metabolism

DNA contains the genetic information that allows all modern living things to function, grow and reproduce. However, it is unclear how long in the 4-billion-year

Unfortunately, there is no direct evidence of ancient genetic systems, as recovery of DNA from most fossils is impossible. This is because DNA will survive in the environment for less than one million years and slowly degrades into short fragments in solution.[103] Although claims for older DNA have been made, most notably a report of the isolation of a viable bacterium from a salt crystal 250-million years old,[104] these claims are controversial and have been disputed.[105][106]

Uses in technology

Genetic engineering

Modern

Forensics

Bioinformatics

DNA and computation

DNA was first used in computing to solve a small version of the directed

History and anthropology

Because DNA collects mutations over time, which are then inherited, it contains historical information and by comparing DNA sequences, geneticists can infer the evolutionary history of organisms, their

DNA has also been used to look at modern family relationships, such as establishing family relationships between the descendants of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson. This usage is closely related to the use of DNA in criminal investigations detailed above. Indeed, some criminal investigations have been solved when DNA from crime scenes has matched relatives of the guilty individual.[126]

History

DNA was first isolated by

In 1943,

In 1953, based on

In an influential presentation in 1957, Crick laid out the

See also

- Genetic disorder

- Plasmid

- DNA sequencing

- Southern blot

- DNA microarray

- Polymerase chain reaction

- Protein-DNA interaction site predictor

- Phosphoramidite

- Quantification of nucleic acids

References

- ^ )

- ISBN 978-0-12-147951-0.

- PMID 7338906.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - )

- ^ PMID 13054692.

- ^ ISBN 0-7167-4955-6

- ^ a b Abbreviations and Symbols for Nucleic Acids, Polynucleotides and their Constituents IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (CBN) Accessed 03 Jan 2006

- ^ PMID 12657780.

- PMID 13980287.

- PMID 14715921.

- ^ Created from PDB 1D65

- PMID 7432492.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 6236744.

- PMID 7526075.

- PMID 10733978.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10393911.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 7476180.

- PMID 15609994.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15851066.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15389973.

- PMID 15680581.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15520290.

- PMID 1771674.

- PMID 2660364.

- PMID 2215424.

- PMID 16004565.

- ^ PMID 11395412.

- ^ PMID 12042765.

- ^ PMID 17150733.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10966645.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16516932.

- )

- PMID 1914495.

- PMID 2482766.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 7441761.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 9097733.

- PMID 10891271.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12086319.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12486233.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Created from NDB UD0017

- ^ PMID 3907856.

- ^ PMID 9553037.

- PMID 9353250.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 17012276.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12050675.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10338214.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16403636.

- PMID 11782440.

- PMID 16570853.

- PMID 16479578.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 8261512.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Created from PDB 1JDG

- PMID 12885257.),

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10064846.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 2602371.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 6592579.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12947387.

- PMID 1881402.

- PMID 3936066.

- PMID 10799645.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 11562309.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - )

- PMID 15988757.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 11236998.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15596463.

- ^ Created from PDB 1MSW

- PMID 15905142.

- PMID 11827946.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12083509.

- PMID 11178285.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 9893710.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15853876.

- PMID 9305837.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 11498575.

- PMID 12596902.

- PMID 11497996.

- PMID 8178371.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10473346.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Created from PDB 1LMB

- PMID 10966474.

- PMID 15479634.

- PMID 12808131.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 6236744.

- ^ Created from PDB 1RVA

- PMID 8336674.

- ^ PMID 11058099.

- PMID 16246147.

- PMID 15128295.

- ^ ).

- PMID 12045093.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15952889.

- PMID 7514143.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 12516863.

- ^ Created from PDB 1M6G

- PMID 11283701.

- PMID 16619049.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16369571.

- PMID 12431441.

- PMID 12423347.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15217990.

- PMID 11360970.

- PMID 1372984.

- PMID 8469282.

- PMID 11057666.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15866038.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 11734907.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 189942.

- PMID 17172731.

- PMID 11950565.

- PMID 12595138.

- PMID 8016106.

- PMID 9068179.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 2989708.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Colin Pitchfork — first murder conviction on DNA evidence also clears the prime suspect Forensic Science Service Accessed 23 Dec 2006

- ^ "DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents". National Institute of Justice. September 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-262-02506-5

- ISBN 978-0-521-58519-4.

- PMID 14734307.

- ISBN 0879697121.)

{{cite book}}: Text "Cold Spring Harbor," ignored (help); Text "location" ignored (help - PMID 7973651.

- PMID 12524509.

- ^ Ashish Gehani, Thomas LaBean and John Reif. DNA-Based Cryptography. Proceedings of the 5th DIMACS Workshop on DNA Based Computers, Cambridge, MA, USA, 14 – 15 June 1999.

- PMID 11806830.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ Lost Tribes of Israel, NOVA, PBS airdate: 22 February 2000. Transcript available from PBS.org, (last accessed on 4 March 2006)

- ^ Kleiman, Yaakov. "The Cohanim/DNA Connection: The fascinating story of how DNA studies confirm an ancient biblical tradition". aish.com (January 13, 2000). Accessed 4 March 2006.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Shaoni. "Killer convicted thanks to relative's DNA". newscientist.com (20 April 2004). Accessed 22 Dec 06

- PMID 15680349.

- .

- ^ Astbury W (1947). "Nucleic acid". Symp. SOC. Exp. BBL. 1 (66).

- PMID 19871359.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12981234.

- ^ a b Watson J.D. and Crick F.H.C. "A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid". (PDF) Nature 171, 737 – 738 (1953). Accessed 13 Feb 2007.

- ^ Nature Archives Double Helix of DNA: 50 Years

- ^ Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate. Franklin R. and Gosling R.G.Nature 171, 740 – 741 (1953)Nature Archives Full Text (PDF)

- ^ Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids. Wilkins M.H.F., A.R. Stokes A.R. & Wilson, H.R. Nature 171, 738 – 740 (1953)Nature Archives (PDF)

- ^ Evidence for 2-Chain Helix in Crystalline Structure of Sodium Deoxyribonucleate. Franklin R. and Gosling R.G. Nature 172, 156 – 157 (1953)Nature Archives, full text (PDF)

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962 Nobelprize .org Accessed 22 Dec 06

- ^ Crick, F.H.C. On degenerate templates and the adaptor hypothesis (PDF). genome.wellcome.ac.uk (Lecture, 1955). Accessed 22 Dec 2006

- PMID 16590258.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968 Nobelprize.org Accessed 22 Dec 06

Further reading

- Clayton, Julie. (Ed.). 50 Years of DNA, Palgrave MacMillan Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1-40-391479-8

- Judson, Horace Freeland. The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-87-969478-4

- ISBN 978-0-48-668117-7; the definitive DNA textbook, revised in 1994, with a 9 page postscript.

- ISBN 978-0-06-082333-7 2006

- Rose, Steven. The Chemistry of Life, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-027273-4.

- Watson, James D. and Francis H.C. Crick. A structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid (PDF). 25 April 1953.

- Watson, James D. DNA: The Secret of Life ISBN 978-0-375-41546-3.

- Watson, James D. ISBN 978-0-393-95075-5

- Watson, James D. "Avoid boring people and other lessons from a life in science" New York: Random House.

- Calladine, Chris R.; Drew, Horace R.; Luisi, Ben F. and Travers, Andrew A. Understanding DNA, Elsevier Academic Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-12155089-9

DVD

- DNA — The Story of the Pioneers who Changed the World, Windfall Films Production for Channel Four Television & PBS Thirteen-WNET — 2003, PAL [1], NTSC PBS Shop

- DNA interactive PAL [2], NTSC [3], [4]

- DNA: The Secret of Life Carolina Biological

- DNA — Secret of Photo 51 Rosalind Franklin — NOVA documentary (NTSC — Region 1?)

- Cracking the Code of Life NOVA documentary (NTSC — All Regions)

External links

- [5] Crick's personal papers at Mandeville Special Collections Library, Geisel Library, University of California, San Diego

- DNA Interactive (requires Adobe Flash)

- DNA from the beginning

- Double Helix 1953 – 2003 National Centre for Biotechnology Education

- Double helix: 50 years of DNA, Nature

- Rosalind Franklin's contributions to the study of DNA

- U.S. National DNA Day — watch videos and participate in real-time chat with top scientists

- Genetic Education Modules for Teachers — DNA from the Beginning Study Guide

- Listen to Francis Crick and James Watson talking on the BBC in 1962, 1972, and 1974

- PDB Molecule of the Month Seans Potato Business/DNA

- DNA under electron microscope

- DNA at Curlie

- DNA Articles — articles and information collected from various sources

{{McGrawHillAnimation|genetics|Dna%20Replication}}- DNA coiling to form chromosomes

- DISPLAR: DNA binding site prediction on protein

- Dolan DNA Learning Center

- Olby, R. (2003) "Quiet debut for the double helix" Nature 421 (January 23): 402 – 405.

- Basic animated guide to DNA cloning

- DNA the Double Helix Game From the official Nobel Prize web site

Template:Featured article is only for Wikipedia:Featured articles.