James Madison: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 1 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) |

|||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

=== Prelude to war === |

=== Prelude to war === |

||

Congress had repealed the embargo right before Madison became president, but troubles with the British and French continued.<ref name=Rp13>Rutland (1990), p. 13</ref> Although initially promising, Madison's diplomatic efforts to get the British to withdraw the [[Orders in Council (1807)|Orders in Council]], which authorized attacks on American shipping, were rejected by British Foreign Secretary [[George Canning]] in April 1809.<ref>Bradford Perkins, ''Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812'' (1961) [http://www.ucpress.edu/op.php?isbn=9780520009967 full text online]</ref> Aside from U.S. trade with France, the central dispute between the Great Britain and the United States was the [[impressment]] of sailors by the British. During the long and expensive war against France, many British citizens were forced by their own government to join the navy, and many of these conscripts defected to U.S. merchant ships. Unable to tolerate this loss of manpower, the British seized several U.S. ships and forced captured crewmen, some of whom were not in fact not British subjects, to serve in the British navy. This impressment contributed greatly to growing anger towards the British in the United States.<ref>{{harvnb|Wills|2002|pages=81–84}}.</ref> |

Congress had repealed the embargo right before Madison became president, but troubles with the British and French continued.<ref name=Rp13>Rutland (1990), p. 13</ref> Although initially promising, Madison's diplomatic efforts to get the British to withdraw the [[Orders in Council (1807)|Orders in Council]], which authorized attacks on American shipping, were rejected by British Foreign Secretary [[George Canning]] in April 1809.<ref>Bradford Perkins, ''Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812'' (1961) [http://www.ucpress.edu/op.php?isbn=9780520009967 full text online]{{dead link|date=November 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> Aside from U.S. trade with France, the central dispute between the Great Britain and the United States was the [[impressment]] of sailors by the British. During the long and expensive war against France, many British citizens were forced by their own government to join the navy, and many of these conscripts defected to U.S. merchant ships. Unable to tolerate this loss of manpower, the British seized several U.S. ships and forced captured crewmen, some of whom were not in fact not British subjects, to serve in the British navy. This impressment contributed greatly to growing anger towards the British in the United States.<ref>{{harvnb|Wills|2002|pages=81–84}}.</ref> |

||

By August 1809, diplomatic relations with Britain deteriorated as minister [[David Erskine, 2nd Baron Erskine|David Erskine]] was withdrawn and replaced by "hatchet man" [[Francis James Jackson]].<ref name=Rpp43-44>Rutland (1990), pp. 40–44.</ref> Madison however, resisted calls for war, as he was ideologically opposed to the debt and taxes necessary for a war effort.<ref>{{harvnb|Wills|2002|pages=62–63}}</ref> British historian Paul Langford sees the removal in 1809 of Erskine as a major British blunder: |

By August 1809, diplomatic relations with Britain deteriorated as minister [[David Erskine, 2nd Baron Erskine|David Erskine]] was withdrawn and replaced by "hatchet man" [[Francis James Jackson]].<ref name=Rpp43-44>Rutland (1990), pp. 40–44.</ref> Madison however, resisted calls for war, as he was ideologically opposed to the debt and taxes necessary for a war effort.<ref>{{harvnb|Wills|2002|pages=62–63}}</ref> British historian Paul Langford sees the removal in 1809 of Erskine as a major British blunder: |

||

| Line 348: | Line 348: | ||

===Primary sources=== |

===Primary sources=== |

||

* {{cite book|first=James|last=Madison|editor-first=William T.|editor-last=Hutchinson|title=The Papers of James Madison|publisher=Univ. of Chicago Press|year=1962|url=http://www.virginia.edu/pjm/description1.htm|edition=30 volumes published and more planned}}; The main scholarly edition |

* {{cite book|first=James|last=Madison|editor-first=William T.|editor-last=Hutchinson|title=The Papers of James Madison|publisher=Univ. of Chicago Press|year=1962|url=http://www.virginia.edu/pjm/description1.htm|edition=30 volumes published and more planned|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111013211454/http://www.virginia.edu/pjm/description1.htm|archivedate=October 13, 2011|df=mdy-all}}; The main scholarly edition |

||

** [https://founders.archives.gov/about "Founders Online," searchable edition] |

** [https://founders.archives.gov/about "Founders Online," searchable edition] |

||

* {{cite book|first=James|last=Madison|title=Letters & Other Writings Of James Madison Fourth President Of The United States|publisher=J.B. Lippincott & Co|year=1865|edition=called the ''Congress edition''|url=https://books.google.com/?id=pb2s8DG_2WUC&pg=RA1-PR11}} |

* {{cite book|first=James|last=Madison|title=Letters & Other Writings Of James Madison Fourth President Of The United States|publisher=J.B. Lippincott & Co|year=1865|edition=called the ''Congress edition''|url=https://books.google.com/?id=pb2s8DG_2WUC&pg=RA1-PR11}} |

||

Revision as of 02:31, 21 November 2017

James Madison | |

|---|---|

George Hancock | |

| Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation from Virginia | |

| In office 1786–1787 1780–1783 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 16, 1751 Port Conway, Colony of Virginia, British America |

| Died | June 28, 1836 (aged 85) Orange, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Montpelier, Orange, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (founder 1791) |

| Height | 5 ft 4 in (163 cm)[1] |

| Spouse |

Nelly Conway Madison |

| Alma mater | Princeton University |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Colony of Virginia |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1775 |

| Rank | |

James Madison Jr. (March 16 [

Born into a prominent Virginia planting family, Madison served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and the Continental Congress during and after the American Revolutionary War. In the late 1780s, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution to supplant the ineffective Articles of Confederation. After the Convention, Madison became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution, and his collaboration with Alexander Hamilton produced The Federalist Papers, among the most important treatises in support of the Constitution.

After the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, Madison won election to

Madison succeeded Jefferson with a victory in the

Early life and education

James Madison Jr. was born on March 16, 1751, (March 5, 1751,

From age 11 to 16, Madison was sent to study under Donald Robertson, a Scottish instructor who served as a tutor for a number of prominent plantation families in the South. From Robertson, Madison learned mathematics, geography, and modern and classical languages—he became especially proficient in Latin.

His studies at Princeton included Latin, Greek, science, geography, mathematics, rhetoric, and philosophy. Great emphasis was placed on speech and debate also; Madison helped found the American Whig Society, in direct competition to fellow student Aaron Burr's Cliosophic Society. After long hours of study that may have compromised his health,[8] Madison graduated in 1771. After graduation, he remained at Princeton to study Hebrew and political philosophy under the university president, John Witherspoon. He returned to Montpelier in early 1772, still unsure of his future career.[9]

Military service and early political career

In the early 1770s the relationship between the American colonies and Great Britain deteriorated over the issue of British taxation, culminating in the American Revolutionary War, which began in 1775. In 1774, Madison took a seat on the local Committee of Safety, a pro-revolution group that oversaw the local militia. This was the first step in a life of public service that his family's wealth facilitated.[10] In October 1775, he was commissioned as the colonel of the Orange County militia, serving as his father's second-in-command until his election as a delegate to the Fifth Virginia Convention, which produced Virginia's first constitution.[11] Of short stature and frequently in poor health, Madison never saw battle in the war, but he rose to prominence in Virginia politics as a wartime leader.[12]

At the Virginia constitutional convention, Madison supported the

Madison served on the Council of State from 1777 to 1779, when he was elected to the

Madison served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1784 to 1786. He continued to correspond with Jefferson and befriended Jefferson's protege, Congressman

Father of the Constitution

Throughout the 1780s, Madison advocated for reform of the Articles of Confederation. He became increasingly worried about the disunity of the states and the weakness of the central government after the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783.[25] As Madison wrote, "a crisis had arrived which was to decide whether the American experiment was to be a blessing to the world, or to blast for ever the hopes which the republican cause had inspired."[26] He was particularly concerned about the inability of Congress to capably conduct foreign policy, which threatened American trade as well as settlement of the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River.[27]

Madison helped arrange the 1785 Mount Vernon Conference, which helped settle disputes regarding navigation rights on the Potomac River and also served as a model for future interstate conferences.[28] At the 1786 Annapolis Convention, he supported the calling of another convention to consider amending the Articles. After winning election to another term in Congress, Madison helped convince the other Congressmen to authorize the Philadelphia Convention for the purposes of proposing new amendments. But Madison had come to believe that the ineffectual Articles had to be superseded by a new constitution, and he began preparing for a convention that would propose an entirely new constitution.[29] Madison ensured that George Washington, who was popular throughout the country, and Robert Morris, who was influential in the critical state of Pennsylvania, would both broadly support Madison's plan to implement a new constitution.[30]

As a quorum was being reached for the Philadelphia Convention to begin, the 36-year-old Madison wrote what became known as the Virginia Plan, an outline for a new constitution.[31] Madison worked with his fellow members of the Virginia delegation, especially Edmund Randolph and George Mason, to create and present the plan to the convention.[32] The plan called for three branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial), a bicameral Congress apportioned by population, and a Council of Revision composed of members of the executive and judicial branches which would have the right to veto laws passed by Congress. Reflecting the centralization of power envisioned by Madison, the Virginia Plan granted the United States Senate the power to abrogate any law passed by state governments.[33] Many delegates were surprised to learn that the plan called for the abrogation of the Articles and the creation of a new constitution, to be ratified by special conventions in each state rather than by the state legislatures. Nonetheless, with the assent of prominent attendees such as Washington and Benjamin Franklin, the delegates went into a secret session to consider a new constitution.[34]

During the course of the Convention, Madison spoke over two hundred times, and his fellow delegates rated him highly. William Pierce wrote that "... every Person seems to acknowledge his greatness. In the management of every great question he evidently took the lead in the Convention ... he always comes forward as the best informed Man of any point in debate." Madison recorded the unofficial minutes of the convention, and these have become the only comprehensive record of what occurred. The historian Clinton Rossiter regarded Madison's performance as "a combination of learning, experience, purpose, and imagination that not even Adams or Jefferson could have equaled."[35]

Though the Virginia Plan was an outline rather than a draft of a possible constitution, and though it was extensively changed during the debate its use at the convention has led many to call Madison the "Father of the Constitution".

The ultimate question before the convention, Wood notes, was not how to design a government but whether the states should remain sovereign, whether sovereignty should be transferred to the national government, or whether the constitution should settle somewhere in between.[38] Most of the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention wanted to empower the federal government to raise revenue and protect property rights.[39] Those, like Madison, who thought democracy in the state legislatures was excessive and insufficiently "disinterested", wanted sovereignty transferred to the national government, while those who did not think this a problem, wanted to fix the Articles of Confederation. Even many delegates who shared Madison's goal of strengthening the central government reacted strongly against the extreme change to the status quo envisioned in the Virginia Plan. Though Madison lost most of his battles over how to amend the Virginia Plan, in the process he increasingly shifted the debate away from a position of pure state sovereignty. Since most disagreements over what to include in the constitution were ultimately disputes over the balance of sovereignty between the states and national government, Madison's influence was critical. Wood notes that Madison's ultimate contribution was not in designing any particular constitutional framework, but in shifting the debate toward a compromise of "shared sovereignty" between the national and state governments.[38][40]

The Federalist Papers and ratification debates

The Philadelphia Convention ended in September 1787, and the

Madison ensured that his writings were delivered to Randolph, Mason, and other prominent Virginia anti-federalists, as those opposed to the ratification of the Constitution were known.[46] Consensus held that if Virginia, the most populous state at the time, did not ratify the Constitution, the new national government would not likely succeed. When the Virginia Ratifying Convention began on June 2, 1788, the Constitution had not yet been ratified by the required nine states. New York, the second largest state and a bastion of anti-federalism, would likely not ratify it without Virginia, and Virginia's exclusion from the new government would disqualify George Washington from being the first president. Arguably the most prominent anti-federalist, the powerful orator Patrick Henry, was a delegate and had a following in the state second only to Washington. Initially Madison did not want to stand for election to the Virginia ratifying convention, but was persuaded to do so due to the strength of the anti-federalists.[47] At the start of the convention, Madison knew that most delegates had already made up their mind about how to vote, and he focused his efforts on winning the support of the relatively small number of undecided delegates.[48]

Although Henry was by far the more powerful and dramatic speaker, Madison's expertise on the subject he had long argued for allowed him to respond with rational arguments to Henry's emotional appeals.[49] Madison persuaded prominent figures such as Randolph to change their position and support it at the ratifying convention. Randolph's switch likely changed the votes of several more anti-federalists.[50] On June 25, 1788, the convention voted 89–79 to ratify the Constitution, making it the tenth state to do so.[51] New York ratified the constitution the following month, and Washington won the country's first presidential election.

Member of Congress

Election to Congress and adviser to Washington

After Virginia ratified the constitution, Madison returned to New York to resume his duties in the Congress of the Confederation. At the request of Washington, Madison sought a seat in the United States Senate, but his election was blocked by Patrick Henry. Madison then decided to run for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. At Henry's behest, the Virginia legislature created congressional districts designed to deny Madison a seat, and Henry recruited a strong challenger to Madison in James Monroe. Locked in a difficult race against Monroe, Madison promised to support a series of constitutional amendments to protect individual liberties.[52] Madison's promise paid off, as he won election to Congress with 57% of the vote.[53]

Early in his tenure, Madison was a principal adviser of President Washington, who looked to Madison as the person who best understood the constitution.[52] Madison helped Washington write his first inaugural address, and also prepared the official House response to the address. He set the legislative agenda of the 1st Congress and helped establish and staff the first three Cabinet departments. He also helped arrange for the appointment of Thomas Jefferson as the inaugural Secretary of State.[54]

Bill of Rights

Though no state conditioned ratification of the constitution on a bill of rights, several states came close, and the issue almost prevented the constitution from being ratified.[55] Madison had opposed proposals for a bill of rights throughout the ratification process, but while running for Congress he had pledged to support a bill of rights. In the 1st Congress he took the lead in pressing for the passage of several constitutional amendments that would form the United States Bill of Rights.[56] Madison feared that the states would call for a new constitutional convention if Congress failed to pass a bill of rights. He also believed that the constitution did not sufficiently protect the national government from excessive democracy and parochialism, so he saw the amendments as mitigation of these problems. On June 8, 1789, Madison introduced his bill proposing amendments consisting of nine articles consisting of up to 20 potential amendments. The House passed most of the amendments, but rejected Madison's idea of placing them in the body of the Constitution. Instead, it adopted 17 amendments to be attached separately and sent this bill to the Senate.[57][58]

The Senate edited the amendments still further, making 26 changes of its own, and condensing their number to twelve.[59] Madison's proposal to apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government was eliminated, as was his final proposed change to the preamble.[60] A House–Senate Conference Committee then convened to resolve the numerous differences between the two Bill of Rights proposals. On September 24, 1789, the committee issued its report, which finalized 12 Constitutional Amendments for the House and Senate to consider. This version was approved by joint resolution of Congress on September 25, 1789.[61][62] Of the proposed twelve Amendments, Articles Three through Twelve were ratified as additions to the Constitution on December 15, 1791, were renumbered one through ten, and became the Bill of Rights.[63] Proposed Article Two became part of the Constitution in 1992 as the Twenty-seventh Amendment, while proposed Article One is technically still pending before the states.[64] Madison was disappointed that the Bill of Rights did not include protections against actions by state governments, but passage of the document mollified some critics of the original constitution and shored up Madison's support in Virginia.[65]

In proposing the Bill of Rights, Madison considered over two hundred amendments that had been proposed at the state ratifying conventions. While most of the amendments he proposed were drawn from these conventions, he was largely responsible for the portions of the Bill of Rights that guarantee freedom of the press, protection of property from government seizure, and jury trials.[65] He initially introduced an amendment that guaranteed all citizens the right to a jury trial in all civil cases where there was $20 or more at stake. While the original amendment failed, the guaranty of a civil jury trial in federal cases was incorporated into the Bill of Rights as the Seventh Amendment.[66]

Founding the Democratic-Republican Party

As the 1790s progressed, the Washington administration became polarized among two main factions. One was led by Jefferson and Madison, broadly represented Southern interests, and sought close relations with France and westward expansion. The other was led by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, broadly represented Northern financial interests, and favored close relations with Britain.[67] In 1790, Hamilton introduced an ambitious economic program that called for the federal assumption of state debts and the funding of that debt through the issuance of federal securities. Hamilton's plan favored Northern speculators and was disadvantageous to states such as Virginia that had already paid off most of their debt, and Madison emerged as one of the principal Congressional opponents of the plan.[68] After prolonged legislative deadlock, Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton agreed to the Compromise of 1790, which provided for the enactment of Hamilton's assumption plan through the Funding Act of 1790. In return, Congress passed the Residence Act, which established the federal capital district of Washington, D.C. on the Potomac River.[69] In 1791, Hamilton introduced a plan that called for the establishment of a national bank, which would provide loans to emerging industries and oversee the money supply. Madison objected to the bank, arguing that its creation was not authorized by the constitution. After Congress passed a bill to create the First Bank of the United States, Washington carefully considered vetoing the bill, but ultimately chose to sign it in February 1791. With the passage of much of Hamilton's economic program, Madison came to fear the growing influence of Northern moneyed interests, which he believed would dominate the fledgling republic under Hamilton's plans. Madison also lost much of his influence in the Washington administration, as Washington increasingly turned to Jefferson and Hamilton for advice.[70]

When Britain and France went to war in 1793, the U.S. was caught in the middle. The 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France was still in effect, yet most of the new country's trade was with Britain. Madison and Jefferson continued to look favorably upon the French Revolution despite its increasingly violent nature, but Washington proclaimed American neutrality.[71] War with Britain became imminent in 1794, after the British seized hundreds of American ships that were trading with French colonies. Madison believed that the United States was stronger than Britain, and that a trade war with Britain, although risking a real war by that government, would probably succeed, and allow Americans to assert their independence fully. Great Britain, he charged, "has bound us in commercial manacles, and very nearly defeated the object of our independence." According to Varg, Madison discounted the more powerful British military when the latter declared "her interests can be wounded almost mortally, while ours are invulnerable." The British West Indies, Madison maintained, could not live without American foodstuffs, but Americans could easily do without British manufactures. He concluded, "it is in our power, in a very short time, to supply all the tonnage necessary for our own commerce".[72] Washington avoided a trade war and instead secured friendly trade relations with Britain through the Jay Treaty of 1794. Madison's harsh and unsuccessful opposition to the treaty led to a permanent break with Washington, ending a long friendship.[73]

The debate over the Jay Treaty helped solidify the growing divide between the country's first major political parties.

Though he was out of office, Madison remained a prominent Democratic-Republican leader in opposition to the administration of Adams.

Marriage and family

Madison was married for the first time at the age of 43; on September 15, 1794, James Madison married

Dolley Madison put her social gifts to use when the couple lived in Washington, beginning when he was Secretary of State. With the White House still under construction, she advised as to its furnishings and sometimes served as First Lady for ceremonial functions for President Thomas Jefferson, a widower and friend. When her husband was president, she created the role of First Lady, using her social talents to advance his program. She is credited with adding to his popularity in office.[citation needed]

Madison's father died in 1801 and at age 50, Madison inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other holdings, and his father's 108 slaves. He had begun to act as a steward of his father's properties by 1780.[86]

United States Secretary of State 1801–1809

Jefferson wanted to oversee

Early in Jefferson's presidency, the United States learned that

Many contemporaries and later historians, such as Ron Chernow, noted that Madison and President Jefferson ignored their "strict construction" of the Constitution to take advantage of the purchase opportunity. Jefferson would have preferred a constitutional amendment authorizing the purchase, but did not have time nor was he required to do so. The Senate quickly ratified the treaty providing for the purchase. The House, with equal alacrity, passed enabling legislation.[91] The Jefferson administration argued that the purchase had included West Florida, but France refused to acknowledge this and Florida remained under the control of Spain.[92]

With the wars raging in Europe, Madison tried to maintain American neutrality, and insisted on the legal rights of the U.S. as a neutral party under international law. Neither London nor Paris showed much respect, however, and the situation deteriorated during Jefferson's second term. After Napoleon achieved victory at over his enemies in continental Europe at the Battle of Austerlitz, he became more aggressive and tried to starve Britain into submission with an embargo that was economically ruinous to both sides. Madison and Jefferson also decided on an embargo to punish Britain and France, forbidding American trade with any foreign nation. The embargo failed in the United States just as it did in France, and caused massive hardships up and down the seaboard, which depended on foreign trade. The Federalists made a comeback in the Northeast by attacking the embargo, which was allowed to expire just as Jefferson was leaving office.[93]

Election of 1808

Speculation regarding Madison's potential succession of Jefferson commenced early in Jefferson's first term. Madison's status in the party was damaged by his association with the embargo, which was unpopular throughout the country but especially in the Northeast.[94] With the Federalists collapsing as a national party after 1800, much of the opposition to Madison and the Jefferson administration came from other members of the Democratic-Republican Party.[95] Madison became the target of attacks from Congressman John Randolph, a leader of the tertium quids. Randolph criticized what he saw as the Jefferson administration's abuses of power and sought to derail Madison's potential presidency in favor of a Monroe presidency.[96] Many northerners also hoped that Vice President George Clinton could unseat Madison as Jefferson's successor. Despite this opposition, Madison won his party's presidential nomination at the January 1808 congressional nominating caucus.[97] The Federalist Party mustered little strength outside New England, and Madison easily defeated Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.[98] At a height of only five feet, four inches (163 cm), and never weighing more than 100 pounds, Madison became the most diminutive president.[99]

Presidency 1809–1817

Upon his inauguration in 1809, Madison immediately faced opposition to his planned nomination of

Prelude to war

Congress had repealed the embargo right before Madison became president, but troubles with the British and French continued.[103] Although initially promising, Madison's diplomatic efforts to get the British to withdraw the Orders in Council, which authorized attacks on American shipping, were rejected by British Foreign Secretary George Canning in April 1809.[104] Aside from U.S. trade with France, the central dispute between the Great Britain and the United States was the impressment of sailors by the British. During the long and expensive war against France, many British citizens were forced by their own government to join the navy, and many of these conscripts defected to U.S. merchant ships. Unable to tolerate this loss of manpower, the British seized several U.S. ships and forced captured crewmen, some of whom were not in fact not British subjects, to serve in the British navy. This impressment contributed greatly to growing anger towards the British in the United States.[105]

By August 1809, diplomatic relations with Britain deteriorated as minister David Erskine was withdrawn and replaced by "hatchet man" Francis James Jackson.[106] Madison however, resisted calls for war, as he was ideologically opposed to the debt and taxes necessary for a war effort.[107] British historian Paul Langford sees the removal in 1809 of Erskine as a major British blunder:

- The British ambassador in Washington [Erskine] brought affairs almost to an accommodation, and was ultimately disappointed not by American intransigence but by one of the outstanding diplomatic blunders made by a Foreign Secretary. It was Canning who, in his most irresponsible manner and apparently out of sheer dislike of everything American, recalled the ambassador Erskine and wrecked the negotiations, a piece of most gratuitous folly. As a result, the possibility of a new embarrassment for Napoleon turned into the certainty of a much more serious one for his enemy. Though the British cabinet eventually made the necessary concessions on the score of the Orders-in-Council, in response to the pressures of industrial lobbying at home, its action came too late…. The loss of the North American markets could have been a decisive blow. As it was by the time the United States declared war, the Continental System [of Napoleon] was beginning to crack, and the danger correspondingly diminishing. Even so, the war, inconclusive though it proved in a military sense, was an irksome and expensive embarrassment which British statesman could have done much more to avert.[108]

After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.

War of 1812

Powell 1873

With continued attacks by the British on American shipping, both Madison and the broader American public were ready for war with Britain.[113] Many Americans called for a "second war of independence" to restore honor and stature to the new nation.[114] With Britain in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, many Americans, Madison included, believed that the United States could easily capture Canada, at which point the U.S. could use Canada as a bargaining chip for all other disputes or simply retain control of it.[115] On June 1, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war.[116] The declaration was passed along sectional and party lines, with intense opposition from the Federalists and the Northeast, where the economy had suffered during Jefferson's trade embargo.[117][118]

Madison hurriedly called on Congress to put the country "into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis," specifically recommending enlarging the army, preparing the militia, finishing the military academy, stockpiling munitions, and expanding the navy.[119] Madison faced formidable obstacles—a divided cabinet, a factious party, a recalcitrant Congress, obstructionist governors, and incompetent generals, together with militia who refused to fight outside their states. The most serious problem facing the war effort was lack of unified popular support. There were serious threats of disunion from New England, which engaged in extensive smuggling with Canada and refused to provide financial support or soldiers.[120] In the 1812 presidential election, DeWitt Clinton's candidacy united anti-war Democratic-Republicans with Federalists. Though Madison defeated Clinton, Clinton won a majority of the votes cast by northern electors.[121] Events in Europe also went against the United States. Shortly after the United States declared war, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia, and the failure of that campaign turned the tide against French and towards Britain and her allies.[122]

Military action

Madison hoped that the war would be over in a couple months after the capture of Canada, but his hopes were quickly dashed.[115] Madison had believed the state militias would rally to the flag and invade Canada, but the governors in the Northeast failed to cooperate. Their militias either sat out the war or refused to leave their respective states for action. The senior command at the War Department and in the field proved incompetent or cowardly—the general at Detroit surrendered to a smaller British force without firing a shot. Gallatin discovered the war was almost impossible to fund, since the national bank had been closed and major financiers in the Northeast refused to help.[123] Gallatin was able to convince John Jacob Astor and other merchants to provide loans in support of the war effort, but Congress was forced to pass a bill raising taxes.[124] The American campaign in Canada, led by Henry Dearborn, ended with defeat in the Battle of Stoney Creek.[125] Following these early setbacks, Madison replaced Secretary of War William Eustis with John Armstrong Jr., a New Yorker who had supported Madison in the 1812 election.[126] He also replaced Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton with William Jones, who presided over a naval build-up and abandoned the traditional Jeffersonian emphasis on gunboats.[127]

The British armed American Indians in the Northwest, most notably several tribes allied with the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh. But, after losing control of Lake Erie at the naval Battle of Lake Erie in 1813, the British were forced to retreat. General William Henry Harrison caught up with them at the Battle of the Thames, where he destroyed the British and Indian armies, killed Tecumseh, and permanently destroyed Indian power in the Great Lakes region. Madison remains the only president to lead troops in battle while in office, although that battle (the Battle of Bladensburg in 1814) did not go well for the American side. The British then raided Washington, as Madison headed a dispirited militia. Dolley Madison rescued White House valuables and documents shortly before the British burned the White House, the Capitol and other public buildings.[128][129] In the aftermath of the raid on Washington, Madison dismissed Armstrong as Secretary of War, and Monroe simultaneously served as Secretary of War and Secretary of State until the end of the War of 1812.[130]

After the disastrous start to the War of 1812, Madison accepted a Russian invitation to arbitrate the war and sent Gallatin, John Quincy Adams,

The successful defense of

To most Americans, the quick succession of events at the end of the war (the burning of the capital, the Battle of New Orleans, and the Treaty of Ghent) appeared as though American valor at New Orleans had forced the British to surrender after almost winning. This view, while inaccurate, strongly contributed to the post-war euphoria that persisted for a decade. It also helps explain the significance of the war, even if it was strategically inconclusive. Napoleon was defeated for the last time at the Battle of Waterloo near the end of Madison's presidency, and as the Napoleonic Wars ended, so did the War of 1812 and the attacks on American shipping. Madison's reputation as president improved and Americans came to believe that the United States had established itself as a world power.[138]

Postwar economy and internal improvements

The postwar period of Madison's second term saw the transition into the

Madison had presided over the expiration First Bank of the United States's charter in 1811.[142] However, the war convinced him of the need for a central bank, which he hoped would aid the government in borrowing money and also help curb inflation. In 1816 he signed a bill establishing the Second Bank of the United States.[143] He also approved an effective taxation system based on tariffs, a standing professional military, and some of the internal improvements championed by Clay under Clay's American System. In 1816, pensions were extended to orphans and widows from the War of 1812 for a period of 5 years at the rate of half pay.[144]

Madison urged a variety of measures that he felt were "best executed under the national authority," including federal support for roads and canals that would "bind more closely together the various parts of our extended confederacy."[145] However, in his last act before leaving office, Madison vetoed the Bonus Bill of 1817, which would have financed more internal improvements of roads, bridges, and canals: "Having considered the bill this day presented to me ... I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling this bill with the Constitution of the United States.... The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in ... the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers."[146]

Indian policy

Upon assuming office on March 4, 1809, in his first

Later life

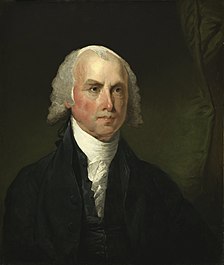

by Gilbert Stuart

When Madison left office in 1817 at age 65, he retired to

In his retirement, Madison occasionally became involved in public affairs, advising

Madison helped Jefferson establish the University of Virginia, though the university was primarily Jefferson's initiative.[154] In 1826, after the death of Jefferson, Madison was appointed as the second Rector of the university. He retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836.

c. 1833

In 1829, at the age of 78, Madison was chosen as a representative to the Virginia Constitutional Convention for revision of the commonwealth's constitution. It was his last appearance as a statesman. The issue of greatest importance at this convention was apportionment. The western districts of Virginia complained that they were underrepresented because the state constitution apportioned voting districts by county. The increased population in the Piedmont and western parts of the state were not proportionately represented by delegates in the legislature. Western reformers also wanted to extend suffrage to all white men, in place of the prevailing property ownership requirement. Madison tried in vain to effect a compromise. Eventually, suffrage rights were extended to renters as well as landowners, but the eastern planters refused to adopt citizen population apportionment. They added slaves held as property to the population count, to maintain a permanent majority in both houses of the legislature, arguing that there must be a balance between population and property represented. Madison was disappointed at the failure of Virginians to resolve the issue more equitably.[155]

In his later years, Madison became highly concerned about his historic legacy. He resorted to modifying letters and other documents in his possession, changing days and dates, adding and deleting words and sentences, and shifting characters. By the time he had reached his late seventies, this "straightening out" had become almost an obsession. As an example, he edited a letter written to Jefferson criticizing Lafayette—Madison not only inked out original passages, but even forged Jefferson's handwriting as well.[156] Historian Drew R. McCoy has said, "During the final six years of his life, amid a sea of personal [financial] troubles that were threatening to engulf him...At times mental agitation issued in physical collapse. For the better part of a year in 1831 and 1832 he was bedridden, if not silenced... Literally sick with anxiety, he began to despair of his ability to make himself understood by his fellow citizens."[157]

Madison died of heart failure at Montpelier on June 28. 1836. He was buried in the Madison Family Cemetery at Montpelier,[158] which is maintained to this day.[159] He was one of the last prominent members of the Revolutionary War generation to die.[150] His will left significant sums to the American Colonization Society, the University of Virginia, and Princeton, as well as $30,000 to his wife, Dolly. Left with a smaller sum than Madison had intended, Dolly would suffer financial troubles until her own death in 1849.[160]

Political and religious views

Federalism

| External videos | |

|---|---|

During his first stint in Congress in the 1780s, Madison came to favor amending the Articles of Confederation to provide for a stronger central government.[161] In the 1790s, he led the opposition to Hamilton's centralizing policies and the Alien and Sedition Acts.[162] According to Chernow, Madison's support of the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in the 1790s "was a breathtaking evolution for a man who had pleaded at the Constitutional Convention that the federal government should possess a veto over state laws."[81] The historian Gordon S. Wood says that Lance Banning, as in his Sacred Fire of Liberty (1995), is the "only present-day scholar to maintain that Madison did not change his views in the 1790s."[163] In claiming this, Banning downplays Madison's nationalism in the 1780s.[163] During and after the War of 1812, Madison came to support several policies he had opposed in the 1790s, including the national bank, a strong navy, and direct taxes.[127]

Wood notes that many historians struggle to understand Madison, but Wood looks at him in the terms of Madison's own times—as a nationalist but one with a different conception of nationalism from that of the Federalists.[163] Gary Rosen and Banning use other approaches to suggest Madison's consistency.[164][165][166]

Religion

Although educated by Presbyterian clergymen, young Madison was an avid reader of English deist tracts.[167] As an adult, Madison paid little attention to religious matters. Though most historians have found little indication of his religious leanings after he left college,[168] some scholars indicate he leaned toward deism.[169][170] Others maintain that Madison accepted Christian tenets and formed his outlook on life with a Christian world view.[171] Regardless of his own religious beliefs, Madison believed in religious liberty, and he advocated for Virginia's disestablishment of the Anglican Church throughout the late 1770s and 1780s.[172] he also opposed the appointments of chaplains for Congress and the armed forces, arguing that the appointments produce religious exclusion as well as political disharmony.[173]

Slavery

Madison grew up on a plantation that made use of slave labor and he viewed the institution as a necessary part of the Southern economy, though he was troubled by the instability of a society that depended on a large enslaved population.

Legacy

The historian Garry Wills wrote, "Madison's claim on our admiration does not rest on a perfect consistency, any more than it rests on his presidency. He has other virtues. ... As a framer and defender of the Constitution he had no peer. ... The finest part of Madison's performance as president was his concern for the preserving of the Constitution. ... No man could do everything for the country—not even Washington. Madison did more than most, and did some things better than any. That was quite enough."[179]

Montpelier, his family's plantation, has been designated a

-

James Madison was honored on a Postage Issue of 1894

-

James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., established in 1908

-

Presidential Dollarof James Madison

-

"Madison Cottage" on the site of the Fifth Avenue Hotel atMadison Square, New York City, 1852

-

Auction of books of James Madison's library, Orange County, Virginia, 1854

See also

- Republicanism

- Report of 1800, produced by Madison to support the Virginia Resolutions

- US Presidents on US postage stamps

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of Presidents of the United States, sortable by previous experience

References

- ^ Kane, Joseph (2001). Facts About the Presidents. H.W. Wilson. p. 590.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 12

- ^ a b "The Life of James Madison". James Madison's Montpelier. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Boyd-Rush, Dorothy. "Molding a founding father". Montpelier. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Life of James Madison". The Montpelier Foundation. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Mills, W. Jay (2002). "Historic Houses of New Jersey". GET NJ. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Brennan, Daniel. "Did James Madison suffer a nervous collapse due to the intensity of his studies?". Princeton University, Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 51.

- ^ a b Stagg, J.A. (ed.). "James Madison: Life Before the Presidency". Univ. of Virginia Miller Center. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 12–13

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 14–15

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 17–18

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 57.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 48–49

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 59–60

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 65–66

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 96–97

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 96–98

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, p. xxiv

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 108–109, 127

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 136–137

- ^ a b Wood 2011, p. 104

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 96–97, 128–130

- ^ Rutland 1987, p. 14.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 129–130

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 137–138

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 138–139, 144

- ^ Rutland 1987, pp. 14–21.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 150–151

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 140–141

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Rutland 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 152–166, 171

- ^ a b Wood 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 148–149

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 164–165

- ^ Bernstein 1987, p. 199.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 165–166

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed. (1961). The Federalist Papers. Penguin Putnam, Inc. pp. ix, xiii.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 31–35.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 174–175

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 179–180

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 135.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 182–183

- ^ a b Wills 2002, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 148–50.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 189–193, 203

- ^ Matthews 1995, p. 130.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 195–197

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 195–97.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875, Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 1st Congress, 1st Session". The Library of Congress. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 237.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 232.

- ISBN 9781455604586. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ISBN 9781455604579. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "The Charters of Freedom: The Bill of Rights". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Kenneth R., ed. (2013). "The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the U.S." (PDF). GPO. p. 49. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 197–199

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 207–208

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 213–217

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 217–220

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 221–224

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 261–262

- ^ Varg, Paul A. (1963). Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers. Michigan State Univ. Press. p. 74.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 38–44.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 38–44.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 279–280

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 305–306

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 311–312

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 317–318

- ^ a b Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 321–322

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 48–49.

- ^ ISBN 9780143034759. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 350–351

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 357–361

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 377.

- ^ "Book of Members, American Academy of Arts and Sciences" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Elizabeth Dowling (2012). A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 373–374

- ^ a b Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 374–376

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 382–389

- ^ Ketcham 1990, pp. 419–21

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Perkins, Bradford (1974). Embargo: Alternative to War, in Essays on the Early Republic 1789–1815. Leonard Levy (Ed.). Dryden Press. p. 324.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 457–458

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 438–439

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 434–435

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 457–459

- ^ Rutland 1990, p. 5.

- ISBN 9781400064823. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Rutland 1990, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Rutland 1990, pp. 32–33, 51, 55.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 497–499

- ^ Rutland (1990), p. 13

- ^ Bradford Perkins, Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812 (1961) full text online[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Rutland (1990), pp. 40–44.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 62–63

- ^ Paul Langford, The eighteenth century: 1688-1815 (1976) p 228

- ^ Rutland (1990), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Rutland (1990), pp. 46–47

- ^ Rutland (2012), p. 57

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 500–502

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Norman K. Risjord, "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks, and the Nation's Honor," William And Mary Quarterly, 1961 18(2): 196–210. in JSTOR

- ^ a b c Wills 2002, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Rutland 1987, pp. 217–24.

- ^ Ketcham (1971), James Madison, pp. 508–09

- ^ Ketcham (1971), James Madison, pp. 509–15

- ^ Stagg, 1983.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 510–511

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Short History (U. of Illinois Press, 1995)

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 523–527

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 122–23.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 518–519

- ^ a b Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 521–522

- ^ Thomas Fleming, "Dolley Madison Saves The Day" Smithsonian 40#12 (2010): 50–56.

- ^ Anthony Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814 (2013).

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 541–545

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore, The Naval War of 1812, pp. 147–52, The Modern Library, New York, NY.

- ^ Rowen, Bob, "American Privateers in the War of 1812," paper presented to the New York Military Affairs Symposium, Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 2001, <http://nymas.org/warof1812paper/paperrevised2006.html>, retrieved 6-6-11.

- ISBN 9780313316876.

- ^ "The Star-Spangled Banner and the War of 1812," Encyclopedia Smithsonian <http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmah/starflag.htm>, retrieved 3-10-08.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 130–31.

- ^ Reilly, Robin, The British at the Gates: The New Orleans Campaign in the War of 1812, 1974.

- ^ "Second War of American Independence," America's Library Web site <http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/madison/aa_madison_war_1.html> retrieved, 6-6-11.

- ^ Rutland (1988), p. 188

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 547–548

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 559–560

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 559–563

- ^ Rosen 1999, pp. 171–73 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRosen1999 (help).

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 558–559

- ISBN 9781452276328. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Banning, Lance, ed. (2004). "Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle". Liberty Fund.

- ^ "Madison's Veto of the Bonus Bill, March 3, 1817". Constitution Society. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Rutland 1990, p. 20.

- ^ a b Rutland 1990, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d Rutland 1990, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 608–609

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 578–581

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 589–591

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 603–604

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 585

- ^ Keysaar 2009, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 162.

- ^ McCoy 1989, p. 151.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 4.

- ^ The Life of James Madison | James Madison's Montpelier

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 609–611

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 85–86

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 232–234

- ^ a b c Wood, Gordon S. (2006). "Is there a James Madison Problem? in "Liberty and American Experience in the Eighteenth Century", Womersley, David (ed.)". Liberty Fund. p. 425. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Rosen, Gary (1999). American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of the Founding. University Press of Kansas. pp. 2–4, 6–9, 140–75.

- ^ Banning 1995, pp. 7–9, 161, 165, 167, 228–31, 296–98, 326–27, 330–33, 345–46, 359–61, 371 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBanning1995 (help)

- ^ Banning 1995, pp. 78–79 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBanning1995 (help).

- ISBN 9780801884832. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ISBN 9780739105702.

- ISBN 9780495913474. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ISBN 9781135579753. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 47.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 106–107

- ^ Madison, James (1817). "Detached Memoranda". Founders Constitution. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 26, 200–202

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 162–163

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 156–157

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 200–201

- ^ Burstein and Isenberg 2010, pp. 607–608

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 164.

Sources

- Banning, Lance (1995). Jefferson & Madison: Three Conversations from the Founding. Madison House.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Banning, Lance (1995). The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Founding of the Federal Republic. Cornell University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bernstein, Richard B. (1987). Are We to be a Nation?; The Making of the Constitution. Harvard Univ. Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burstein, Andrew; Isenberg, Nancy (2010). Madison and Jefferson. Random House.

- Ketcham, Ralph (1990). James Madison: A Biography. Univ. of Virginia Press. ), scholarly biography; paperback ed.

- Keysaar, Alexander (2009). The Right to Vote. Basic Books. )

- Labunski, Richard (2006). James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford Univ. Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCoy, Drew R. (1989). The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matthews, Richard K. (1995). If Men Were Angels : James Madison and the Heartless Empire of Reason. University Press of Kansas.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosen, Gary (1999). American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding. University Press of Kansas.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rutland, Robert A. (1987). James Madison: The Founding Father. Macmillan Publishing Co. )

- Rutland, Robert A. (1990). The Presidency of James Madison. Univ. Press of Kansas. ) scholarly overview of his two terms.

- Rutland, Robert A., ed. (1994). James Madison and the American Nation, 1751–1836: An Encyclopedia. Simon & Schuster.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stewart, David (2007). The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. Simon and Schuster.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wills, Garry (2002). James Madison. Times Books. ) Short bio.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2011). The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States. The Penguin Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

Biographies

- Brant, Irving (1952). "James Madison and His Times". American Historical Review. 57 (4): 853–70.

- Brant, Irving (1941–1961). James Madison. 6 volumes., the standard scholarly biography

- Brant, Irving (1970). The Fourth President; a Life of James Madison. Easton Press. single volume condensation of 6-vol biography

- Broadwater, Jeff. (2012). James Madison: A Son of Virginia and a Founder of a Nation. University of North Carolina Press.

- Brookhiser, Richard. (2011). James Madison. Basic Books.

- Chadwick, Bruce. (2014). James and Dolley Madison: America's First Power Couple. Prometheus Books. detailed popular history

- Cheney, Lynne (2014). James Madison: A Life Reconsidered. Viking.

- Gay, Sydney Howard (1894). James Madison. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. Ebook

- Gutzman, Kevin (2012). James Madison and the Making of America. St. Martin's Press.

- Feldman, Noah (2017). The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President. Random House.

- Stewart, David O. (2016). Madison's Gift: Five Partnerships That Built America. Simon & Schuster.

- Rakove, Jack (2002). James Madison and the Creation of the American Republic (2nd ed.). Longman.

- Riemer, Neal (1968). James Madison. Washington Square Press.

- Wills, Garry (2015). James Madison: The American Presidents Series: The 4th President, 1809–1817. Times Books.

Analytic studies

- Bordewich, Fergus M. (2016). The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government. Simon and Schuster.

- Brant, Irving (1968). James Madison and American Nationalism. Van Nostrand Co. short survey with primary sources

- Dragu, Tiberiu; Fan, Xiaochen; Kuklinski, James (March 2014). "Designing checks and balances". )

- Elkins, Stanley M.; McKitrick, Eric. (1995). The Age of Federalism. Oxford University Press.

- Everdell, William (2000). The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans. Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Gabrielson, Teena (September 2009). "James Madison's Psychology of Public Opinion". Political Research Quarterly. 62: 431–44.

- Harbert, Earl, ed. (1986). Henry Adams: History of the United States during the Administrations of James Madison. Library of America.

- Kasper, Eric T. (2010). To Secure the Liberty of the People: James Madison's Bill of Rights and the Supreme Court's Interpretation. Northern Illinois University Press.

- Kernell, Samuel, ed. (2003). James Madison: the Theory and Practice of Republican Government. Stanford Univ. Press.

- Kester, Scott J. (2008). The Haunted Philosophe: James Madison, Republicanism, and Slavery. Lexington Books.

- McCoy, Drew R. (1980). The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America. W.W. Norton.

- Muñoz, Vincent Phillip. (February 2003). "James Madison's Principle of Religious Liberty". American Political Science Review. 97 (1): 17–32.

- Read, James H. (2000). Power Versus Liberty: Madison, Hamilton, Wilson and Jefferson. Univ. Press of Virginia.

- Riemer, Neal (March 1954). "The Republicanism of James Madison". Political Science Quarterly. 69 (1): 45–64. JSTOR 2145057.

- Riemer, Neal (1986). James Madison: Creating the American Constitution. Congressional Quarterly.

- Scarberry, Mark S. (April 2009). "John Leland and James Madison: Religious Influence on the Ratification of the Constitution and on the Proposal of the Bill of Rights". Penn State Law Review. 113 (3): 733–800.

- Sheehan, Colleen A. (October 1992). "The Politics of Public Opinion: James Madison's 'Notes on Government". William and Mary Quarterly. 49 (3).

- Sheehan, Colleen (October 2002). "Madison and the French Enlightenment". William and Mary Quarterly. 59 (4): 925–56.

- Sheehan, Colleen (August 2004). "Madison v. Hamilton: The Battle Over Republicanism and the Role of Public Opinion". American Political Science Review. 98 (3): 405–24.

- Sheehan, Colleen (2015). The Mind of James Madison: The Legacy of Classical Republicanism. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Sheehan, Colleen (Winter 2005). "Public Opinion and the Formation of Civic Character in Madison's Republican Theory". Review of Politics. 67 (1): 37–48.

- Sorenson, Leonard R. (1995). Madison on the General Welfare of America: His Consistent Constitutional Vision. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Stagg, John C. A. (October 1976). "James Madison and the Malcontents: The Political Origins of the War of 1812". William and Mary Quarterly. 33 (4): 557–85.

- Stagg, John C. A. (January 1981). "James Madison and the Coercion of Great Britain: Canada, the West Indies, and the War of 1812". William and Mary Quarterly. 38 (1): 3–34.

- Vile, John R.; Pederson, William D.; Williams, Frank J., eds. (2008). James Madison: Philosopher, Founder, and Statesman. Ohio Univ. Press.

- Weiner, Greg. (2012). Madison's Metronome: The Constitution, Majority Rule, and the Tempo of American Politics. Univ. Press of Kansas.

- White, Leonard D. (1967). The Jeffersonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1801–1829. Macmillan.

- Will, George F. (January 23, 2008). "Alumni who changed America, and the world: #1 – James Madison 1771". Princeton Alumni Weekly.

- Wills, Garry (2005). Henry Adams and the Making of America. Houghton Mifflin.

- Woodward, C. Vann, ed. (1974). Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct. Dell Publishing.

Historiography

- Leibiger, Stuart, ed. (2013). A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe. John Wiley and Sons.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2006). Is There a 'James Madison Problem'?. Penguin Press.

Primary sources

- Madison, James (1962). Hutchinson, William T. (ed.). The Papers of James Madison (30 volumes published and more planned ed.). Univ. of Chicago Press. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); The main scholarly edition - Madison, James (1865). Letters & Other Writings Of James Madison Fourth President Of The United States (called the Congress edition ed.). J.B. Lippincott & Co.

- Madison, James (1900–1910). Hunt, Gaillard (ed.). The Writings of James Madison. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Madison, James (1982). Cooke, Jacob E. (ed.). The Federalist. Wesleyan Univ. Press.

- Madison, James (1987). Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison. W.W. Norton.

- Madison, James (1995). Myers, Marvin (ed.). Mind of the Founder: Sources of the Political Thought of James Madison. Univ. Press of New England.

- Madison, James (1995). Smith, James M. (ed.). The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776–1826. W.W. Norton.

- Madison, James (1999). Rakove, Jack N. (ed.). James Madison, Writings. Library of America.

- Richardson, James D., ed. (1897). A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, vol. xix. reprints his major messages and reports.

External links

- White House biography

- United States Congress. "James Madison (id: M000043)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- James Madison: A Resource Guide at the Library of Congress

- The James Madison Papers, 1723–1836 at the Library of Congress

- The Papers of James Madison, subset of Founders Online from the National Archives

- American President: James Madison (1751–1836) at the Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia

- James Madison at the Online Library of Liberty, Liberty Fund

- Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785) at the U.S. National Archives

- The Papers of James Madison at the Avalon Project

- Montpelier, home of James Madison

- "Memories of Montpelier: Home of James and Dolley Madison", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- "Life Portrait of James Madison", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, April 9, 1999

- "Writings of Jefferson and Madison" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Booknotes interview with William Lee Miller on The Business of May Next: James Madison and the Founding, June 14, 1992.

- Works by James Madison at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Madison at Internet Archive

- Works by James Madison at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- James Madison Personal Manuscripts