Human: Difference between revisions

Added more sources for Omo-Kibish. |

MOS:RELTIME |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

'''Humans''' (''[[Homo sapiens]]'') are the only [[Extant taxon|extant]] members of the [[subtribe]] [[Hominina]]. Together with [[Pan (genus)|chimpanzees]], [[gorilla]]s, and [[orangutan]]s, they are part of the family [[Hominidae]] (the great apes, or ''hominids''). A [[terrestrial animal]], humans are characterized by their [[Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism|erect posture]] and [[Bipedalism|bipedal locomotion]]; high [[manual dexterity]] and heavy tool use compared to other [[animal]]s; open-ended and complex [[Language|language use]] compared to other [[Animal language|animal communications]]; larger, more complex brains than other animals; and highly advanced and organized [[social animal|societies]].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Goodman M, Tagle D, Fitch D, Bailey W, Czelusniak J, Koop B, Benson P, Slightom J |title=Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids |journal=J Mol Evol |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=260–66 |year=1990 |pmid=2109087 |doi=10.1007/BF02099995|bibcode=1990JMolE..30..260G }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Hominidae Classification |work=Animal Diversity Web @ UMich |url=http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/classification/Hominidae.html |accessdate=25 September 2006 |url-status=live |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061005035254/http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/classification/Hominidae.html |archivedate=5 October 2006 }}</ref> |

'''Humans''' (''[[Homo sapiens]]'') are the only [[Extant taxon|extant]] members of the [[subtribe]] [[Hominina]]. Together with [[Pan (genus)|chimpanzees]], [[gorilla]]s, and [[orangutan]]s, they are part of the family [[Hominidae]] (the great apes, or ''hominids''). A [[terrestrial animal]], humans are characterized by their [[Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism|erect posture]] and [[Bipedalism|bipedal locomotion]]; high [[manual dexterity]] and heavy tool use compared to other [[animal]]s; open-ended and complex [[Language|language use]] compared to other [[Animal language|animal communications]]; larger, more complex brains than other animals; and highly advanced and organized [[social animal|societies]].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Goodman M, Tagle D, Fitch D, Bailey W, Czelusniak J, Koop B, Benson P, Slightom J |title=Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids |journal=J Mol Evol |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=260–66 |year=1990 |pmid=2109087 |doi=10.1007/BF02099995|bibcode=1990JMolE..30..260G }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Hominidae Classification |work=Animal Diversity Web @ UMich |url=http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/classification/Hominidae.html |accessdate=25 September 2006 |url-status=live |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061005035254/http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/classification/Hominidae.html |archivedate=5 October 2006 }}</ref> |

||

Early hominins—particularly the [[australopithecine]]s, whose brains and anatomy are in many ways more similar to ancestral non-human [[ape]]s—are less often referred to as "human" than hominins of the genus ''[[Homo]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Tattersall Ian |author2=Schwartz Jeffrey |year=2009 |title=Evolution of the Genus Homo |url= |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |volume=37 |issue= 1|pages=67–92 |doi=10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100202|bibcode=2009AREPS..37...67T }}</ref> Several of these hominins [[Control of fire by early humans|used fire]], [[Early human migrations|occupied much of Eurasia]], and the lineage that gave rise to ''Homo sapiens'' is thought to have diverged in Africa around 500,000 years ago, with the earliest fossil evidence of evidence of early ''Homo sapiens'' appearing (also in Africa) around 300,000 years ago.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Scerri|first=Eleanor M. L.|last2=Thomas|first2=Mark G.|last3=Manica|first3=Andrea|last4=Gunz|first4=Philipp|last5=Stock|first5=Jay T.|last6=Stringer|first6=Chris|last7=Grove|first7=Matt|last8=Groucutt|first8=Huw S.|last9=Timmermann|first9=Axel|last10=Rightmire|first10=G. Philip|last11=d’Errico|first11=Francesco|date=1 August 2018|title=Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?|url=https://www.cell.com/trends/ecology-evolution/abstract/S0169-5347(18)30117-4|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution|language=English|volume=33|issue=8|pages=582–594|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005|issn=0169-5347|pmid=30007846|pmc=6092560}}</ref> The oldest early ''H. sapiens'' fossils were found in [[Jebel Irhoud]], [[Morocco]] dating to about 315,000 years ago.<ref name="EA-20190320">{{cite news |author=University of Huddersfield |title=Researchers shed new light on the origins of modern humans – The work, published in Nature, confirms a dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration |url=https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-03/uoh-nrs032019.php |date=20 March 2019 |work=[[EurekAlert!]] |access-date=23 March 2019 |author-link=University of Huddersfield }}</ref><ref name="SR-20190318">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rito T, Vieira D, Silva M, Conde-Sousa E, Pereira L, Mellars P, Richards MB, Soares P | display-authors = 6 | title = A dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 9 | issue = 1 | pages = 4728 | date = March 2019 | pmid = 30894612 | pmc = 6426877 | doi = 10.1038/s41598-019-41176-3 | bibcode = 2019NatSR...9.4728R }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.inverse.com/article/39908-ancient-human-evolution-science|title=Everything We Learned in One Year About Thousands of Years of Human Evolution|last=Sloat|first=Sarah|date=4 January 2018|website=Inverse|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20180126012411/https://www.inverse.com/article/39908-ancient-human-evolution-science|archivedate=26 January 2018|url-status=live|access-date=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Antón, Susan C. |author2=Swisher III, Carl C. |year=2004 |title=Early Dispersals of homo from Africa |url= |journal=Annual Review of Anthropology |volume=33 |issue= |pages=271–96 |doi=10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144024}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Trinkaus Erik |year=2005 |title=Early Modern Humans |url= |journal=Annual Review of Anthropology |volume=34 |issue= |pages=207–30 |doi=10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.030905.154913}}</ref> Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern [[Ethiopia]] is the oldest [[anatomically modern Homo sapiens]] skeleton currently known (196 ± 5 ka).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hammond|first=Ashley S.|last2=Royer|first2=Danielle F.|last3=Fleagle|first3=John G.|date=Jul 2017|title=The Omo-Kibish I pelvis|journal=Journal of Human Evolution|volume=108|pages=199–219|doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.04.004|issn=1095-8606|pmid=28552208}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fleagle|first=John G.|last2=Brown|first2=Francis H.|last3=McDougall|first3=Ian|date=17 February 2005|title=Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=433|issue=7027|pages=733–736|doi=10.1038/nature03258|issn=1476-4687|pmid=15716951}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=López|first=Saioa|last2=van Dorp|first2=Lucy|last3=Hellenthal|first3=Garrett|date=2016-04-21|title=Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4844272/|journal=Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online|volume=11|issue=Suppl 2|pages=57–68|doi=10.4137/EBO.S33489|issn=1176-9343|pmc=4844272|pmid=27127403}}</ref> Humans began to exhibit evidence of [[behavioral modernity]] at least by about 100-70,000 years ago<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Henshilwood | first1 = C. S. | last2 = d'Errico | first2 = F. | last3 = Yates | first3 = R. | last4 = Jacobs | first4 = Z. | last5 = Tribolo | first5 = C. | last6 = Duller | first6 = G. A. T. | last7 = Mercier | first7 = N. | last8 = Sealy | first8 = J. C. | last9 = Valladas | first9 = H. | last10 = Watts | first10 = I. | last11 = Wintle | first11 = A. G. | year = 2002 | title = Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa | url = | journal = Science | volume = 295 | issue = 5558| pages = 1278–1280 | doi=10.1126/science.1067575 | pmid=11786608| bibcode = 2002Sci...295.1278H }}</ref><ref name="Backwell">{{cite journal | author = Backwell L, d'Errico F, Wadley L | year = 2008 | title = Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa | url = | journal = Journal of Archaeological Science | volume = 35 | issue = | pages = 1566–1580 | doi = 10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006 }}</ref><ref name="McBrearty Brooks 2000">{{cite journal|last1=McBrearty|first1=Sally|last2=Brooks|first2=Allison|date=2000|title=The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior|journal=Journal of Human Evolution|volume=39|issue=5|pages=453–563|doi=10.1006/jhev.2000.0435|pmid=11102266}}</ref><ref name="Henshilwood Marean 2003">{{cite journal|last1=Henshilwood|first1=Christopher|last2=Marean|first2=Curtis|date=2003|title=The Origin of Modern Human Behavior: Critique of the Models and Their Test Implications|journal=Current Anthropology|volume=44|issue=5|pages=627–651|doi=10.1086/377665}}</ref><ref>{{citation|last1=Brown|first1=Kyle S. |last2=Marean| first2=Curtis W. |last3=Herries |first3=Andy I.R. |last4=Jacobs |first4=Zenobia |last5=Tribolo |first5=Chantal |last6=Braun |first6=David |last7=Roberts |first7=David L. |last8=Meyer |first8=Michael C. |author9=Bernatchez, J. |date=14 August 2009 |title=Fire as an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans| journal=Science |volume=325 |issue=5942 |pages=859–862 |doi=10.1126/science.1175028 |pmid=19679810|bibcode=2009Sci...325..859B }}</ref><ref name="Henshilwood et al. 2011">{{cite journal | author = Henshilwood Christopher S | display-authors = etal | year = 2011 | title = A 100,000-Year-Old Ochre-Processing Workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa | url = | journal = Science | volume = 334 | issue = | pages = 219–222 | doi = 10.1126/science.1211535 }}</ref> and (according to recent evidence) as far back as around 300,000 years ago, in the [[Middle Stone Age]],<ref name="Brooks">{{Cite journal|title=Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age|journal=Science|volume=360|issue=6384|pages=90–94|year=2018|doi = 10.1126/science.aao2646|pmid=29545508|vauthors=Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts R, Behrensmeyer AK, Deino AL, Leslie DE, Ambrose SH, Ferguson JR, d'Errico F, Zipkin AM, Whittaker S, Post J, Veatch EG, Foecke K, Clark JB|bibcode=2018Sci...360...90B}}</ref><ref name="The Atlantic-555674">{{cite news |last=Yong |first=Ed |authorlink=Ed Yong |title=A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity - New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species. |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/03/a-deeper-origin-of-complex-human-cultures/555674/ |date=15 March 2018 |work=[[The Atlantic]] |accessdate=15 March 2018 }}</ref><ref name="SahlePLOS1">{{Cite journal |last1=Sahle |first1=Y. |last2=Hutchings |first2=W. K. |last3=Braun |first3=D. R. |last4=Sealy |first4=J. C. |last5=Morgan |first5=L. E. |last6=Negash |first6=A. |last7=Atnafu |first7=B. |editor1-last=Petraglia |editor1-first=Michael D |title=Earliest Stone-Tipped Projectiles from the Ethiopian Rift Date to >279,000 Years Ago |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0078092 |journal=PLoS ONE |volume=8 |issue=11 |pages=e78092 |year=2013 |pmid=24236011 |pmc=3827237 |bibcode=2013PLoSO...878092S }}</ref> (with some features of behavioral modernity possibly beginning earlier, and possibly in parallel with evolutionary brain globularization in ''H. sapiens''). In several [[Early human migrations|waves of migration]], ''H. sapiens'' ventured out of Africa and populated most of the world.<ref name="evolutionthe1st4billionyears">{{cite book |title=Evolution: The First Four Billion Years |author=McHenry, H.M |chapter=Human Evolution |editor1=Michael Ruse |editor2=Joseph Travis |year=2009 |publisher=The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |isbn=978-0-674-03175-3 |page=[https://archive.org/details/evolutionfirstfo00mich/page/265 265] |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/evolutionfirstfo00mich/page/265 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Neubauer|first=Simon|last2=Hublin|first2=Jean-Jacques|last3=Gunz|first3=Philipp|date=1 January 2018|title=The evolution of modern human brain shape|url=https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/1/eaao5961|journal=Science Advances|language=en|volume=4|issue=1|pages=eaao5961|doi=10.1126/sciadv.aao5961|issn=2375-2548}}</ref> |

Early hominins—particularly the [[australopithecine]]s, whose brains and anatomy are in many ways more similar to ancestral non-human [[ape]]s—are less often referred to as "human" than hominins of the genus ''[[Homo]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Tattersall Ian |author2=Schwartz Jeffrey |year=2009 |title=Evolution of the Genus Homo |url= |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |volume=37 |issue= 1|pages=67–92 |doi=10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100202|bibcode=2009AREPS..37...67T }}</ref> Several of these hominins [[Control of fire by early humans|used fire]], [[Early human migrations|occupied much of Eurasia]], and the lineage that gave rise to ''Homo sapiens'' is thought to have diverged in Africa around 500,000 years ago, with the earliest fossil evidence of evidence of early ''Homo sapiens'' appearing (also in Africa) around 300,000 years ago.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Scerri|first=Eleanor M. L.|last2=Thomas|first2=Mark G.|last3=Manica|first3=Andrea|last4=Gunz|first4=Philipp|last5=Stock|first5=Jay T.|last6=Stringer|first6=Chris|last7=Grove|first7=Matt|last8=Groucutt|first8=Huw S.|last9=Timmermann|first9=Axel|last10=Rightmire|first10=G. Philip|last11=d’Errico|first11=Francesco|date=1 August 2018|title=Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?|url=https://www.cell.com/trends/ecology-evolution/abstract/S0169-5347(18)30117-4|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution|language=English|volume=33|issue=8|pages=582–594|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005|issn=0169-5347|pmid=30007846|pmc=6092560}}</ref> The oldest early ''H. sapiens'' fossils were found in [[Jebel Irhoud]], [[Morocco]] dating to about 315,000 years ago.<ref name="EA-20190320">{{cite news |author=University of Huddersfield |title=Researchers shed new light on the origins of modern humans – The work, published in Nature, confirms a dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration |url=https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-03/uoh-nrs032019.php |date=20 March 2019 |work=[[EurekAlert!]] |access-date=23 March 2019 |author-link=University of Huddersfield }}</ref><ref name="SR-20190318">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rito T, Vieira D, Silva M, Conde-Sousa E, Pereira L, Mellars P, Richards MB, Soares P | display-authors = 6 | title = A dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 9 | issue = 1 | pages = 4728 | date = March 2019 | pmid = 30894612 | pmc = 6426877 | doi = 10.1038/s41598-019-41176-3 | bibcode = 2019NatSR...9.4728R }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.inverse.com/article/39908-ancient-human-evolution-science|title=Everything We Learned in One Year About Thousands of Years of Human Evolution|last=Sloat|first=Sarah|date=4 January 2018|website=Inverse|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20180126012411/https://www.inverse.com/article/39908-ancient-human-evolution-science|archivedate=26 January 2018|url-status=live|access-date=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Antón, Susan C. |author2=Swisher III, Carl C. |year=2004 |title=Early Dispersals of homo from Africa |url= |journal=Annual Review of Anthropology |volume=33 |issue= |pages=271–96 |doi=10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144024}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Trinkaus Erik |year=2005 |title=Early Modern Humans |url= |journal=Annual Review of Anthropology |volume=34 |issue= |pages=207–30 |doi=10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.030905.154913}}</ref> Discovered in 1967, Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern [[Ethiopia]] is, {{as of|2017|lc=y}}<!-- might be justified to use 2020, but I'm using date of latest cited source -->, the oldest [[anatomically modern Homo sapiens]] skeleton currently known (196 ± 5 ka).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hammond|first=Ashley S.|last2=Royer|first2=Danielle F.|last3=Fleagle|first3=John G.|date=Jul 2017|title=The Omo-Kibish I pelvis|journal=Journal of Human Evolution|volume=108|pages=199–219|doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.04.004|issn=1095-8606|pmid=28552208}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fleagle|first=John G.|last2=Brown|first2=Francis H.|last3=McDougall|first3=Ian|date=17 February 2005|title=Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=433|issue=7027|pages=733–736|doi=10.1038/nature03258|issn=1476-4687|pmid=15716951}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=López|first=Saioa|last2=van Dorp|first2=Lucy|last3=Hellenthal|first3=Garrett|date=2016-04-21|title=Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4844272/|journal=Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online|volume=11|issue=Suppl 2|pages=57–68|doi=10.4137/EBO.S33489|issn=1176-9343|pmc=4844272|pmid=27127403}}</ref> Humans began to exhibit evidence of [[behavioral modernity]] at least by about 100-70,000 years ago<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Henshilwood | first1 = C. S. | last2 = d'Errico | first2 = F. | last3 = Yates | first3 = R. | last4 = Jacobs | first4 = Z. | last5 = Tribolo | first5 = C. | last6 = Duller | first6 = G. A. T. | last7 = Mercier | first7 = N. | last8 = Sealy | first8 = J. C. | last9 = Valladas | first9 = H. | last10 = Watts | first10 = I. | last11 = Wintle | first11 = A. G. | year = 2002 | title = Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa | url = | journal = Science | volume = 295 | issue = 5558| pages = 1278–1280 | doi=10.1126/science.1067575 | pmid=11786608| bibcode = 2002Sci...295.1278H }}</ref><ref name="Backwell">{{cite journal | author = Backwell L, d'Errico F, Wadley L | year = 2008 | title = Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa | url = | journal = Journal of Archaeological Science | volume = 35 | issue = | pages = 1566–1580 | doi = 10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006 }}</ref><ref name="McBrearty Brooks 2000">{{cite journal|last1=McBrearty|first1=Sally|last2=Brooks|first2=Allison|date=2000|title=The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior|journal=Journal of Human Evolution|volume=39|issue=5|pages=453–563|doi=10.1006/jhev.2000.0435|pmid=11102266}}</ref><ref name="Henshilwood Marean 2003">{{cite journal|last1=Henshilwood|first1=Christopher|last2=Marean|first2=Curtis|date=2003|title=The Origin of Modern Human Behavior: Critique of the Models and Their Test Implications|journal=Current Anthropology|volume=44|issue=5|pages=627–651|doi=10.1086/377665}}</ref><ref>{{citation|last1=Brown|first1=Kyle S. |last2=Marean| first2=Curtis W. |last3=Herries |first3=Andy I.R. |last4=Jacobs |first4=Zenobia |last5=Tribolo |first5=Chantal |last6=Braun |first6=David |last7=Roberts |first7=David L. |last8=Meyer |first8=Michael C. |author9=Bernatchez, J. |date=14 August 2009 |title=Fire as an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans| journal=Science |volume=325 |issue=5942 |pages=859–862 |doi=10.1126/science.1175028 |pmid=19679810|bibcode=2009Sci...325..859B }}</ref><ref name="Henshilwood et al. 2011">{{cite journal | author = Henshilwood Christopher S | display-authors = etal | year = 2011 | title = A 100,000-Year-Old Ochre-Processing Workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa | url = | journal = Science | volume = 334 | issue = | pages = 219–222 | doi = 10.1126/science.1211535 }}</ref> and (according to recent evidence) as far back as around 300,000 years ago, in the [[Middle Stone Age]],<ref name="Brooks">{{Cite journal|title=Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age|journal=Science|volume=360|issue=6384|pages=90–94|year=2018|doi = 10.1126/science.aao2646|pmid=29545508|vauthors=Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts R, Behrensmeyer AK, Deino AL, Leslie DE, Ambrose SH, Ferguson JR, d'Errico F, Zipkin AM, Whittaker S, Post J, Veatch EG, Foecke K, Clark JB|bibcode=2018Sci...360...90B}}</ref><ref name="The Atlantic-555674">{{cite news |last=Yong |first=Ed |authorlink=Ed Yong |title=A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity - New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species. |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/03/a-deeper-origin-of-complex-human-cultures/555674/ |date=15 March 2018 |work=[[The Atlantic]] |accessdate=15 March 2018 }}</ref><ref name="SahlePLOS1">{{Cite journal |last1=Sahle |first1=Y. |last2=Hutchings |first2=W. K. |last3=Braun |first3=D. R. |last4=Sealy |first4=J. C. |last5=Morgan |first5=L. E. |last6=Negash |first6=A. |last7=Atnafu |first7=B. |editor1-last=Petraglia |editor1-first=Michael D |title=Earliest Stone-Tipped Projectiles from the Ethiopian Rift Date to >279,000 Years Ago |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0078092 |journal=PLoS ONE |volume=8 |issue=11 |pages=e78092 |year=2013 |pmid=24236011 |pmc=3827237 |bibcode=2013PLoSO...878092S }}</ref> (with some features of behavioral modernity possibly beginning earlier, and possibly in parallel with evolutionary brain globularization in ''H. sapiens''). In several [[Early human migrations|waves of migration]], ''H. sapiens'' ventured out of Africa and populated most of the world.<ref name="evolutionthe1st4billionyears">{{cite book |title=Evolution: The First Four Billion Years |author=McHenry, H.M |chapter=Human Evolution |editor1=Michael Ruse |editor2=Joseph Travis |year=2009 |publisher=The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |isbn=978-0-674-03175-3 |page=[https://archive.org/details/evolutionfirstfo00mich/page/265 265] |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/evolutionfirstfo00mich/page/265 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Neubauer|first=Simon|last2=Hublin|first2=Jean-Jacques|last3=Gunz|first3=Philipp|date=1 January 2018|title=The evolution of modern human brain shape|url=https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/1/eaao5961|journal=Science Advances|language=en|volume=4|issue=1|pages=eaao5961|doi=10.1126/sciadv.aao5961|issn=2375-2548}}</ref> |

||

The spread of the [[world population|large and increasing population]] of humans has profoundly [[Holocene extinction|affected]] much of the biosphere and millions of species worldwide. Advantages that explain this evolutionary success include a [[encephalization|larger brain]] with a well-developed [[neocortex]], [[prefrontal cortex]] and [[temporal lobe]]s, which enable advanced abstract [[reasoning]], [[language]], [[problem solving]], [[sociality]], and culture through social learning. Humans use tools more frequently and effectively than any other animal: they are the only extant species to build fires, [[cooking|cook food]], [[clothing|clothe]] themselves, and create and use numerous other [[technology|technologies]] and [[art]]s. |

The spread of the [[world population|large and increasing population]] of humans has profoundly [[Holocene extinction|affected]] much of the biosphere and millions of species worldwide. Advantages that explain this evolutionary success include a [[encephalization|larger brain]] with a well-developed [[neocortex]], [[prefrontal cortex]] and [[temporal lobe]]s, which enable advanced abstract [[reasoning]], [[language]], [[problem solving]], [[sociality]], and culture through social learning. Humans use tools more frequently and effectively than any other animal: they are the only extant species to build fires, [[cooking|cook food]], [[clothing|clothe]] themselves, and create and use numerous other [[technology|technologies]] and [[art]]s. |

||

Revision as of 03:07, 9 February 2020

| Human Ma Middle Pleistocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| An adult human male (left) and female (right) from the Akha tribe in Northern Thailand. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. sapiens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

Homo sapiens idaltu White et al., 2003Homo sapiens sapiens

| |

| |

Homo sapiens population density

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Species synonymy[1]

| |

Humans (

Early hominins—particularly the

The spread of the

Humans uniquely use such systems of symbolic communication as language and art to express themselves and exchange ideas, and also organize themselves into purposeful groups. Humans create complex

Though most of human existence has been sustained by hunting and gathering in band societies,[27] many human societies transitioned to sedentary agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago,[28] domesticating plants and animals, thus enabling the growth of civilization. These human societies subsequently expanded, establishing various forms of government, religion, and culture around the world, and unifying people within regions to form states and empires. The rapid advancement of scientific and medical understanding in the 19th and 20th centuries permitted the development of fuel-driven technologies and increased lifespans, causing the human population to rise exponentially. The global human population was estimated to be near 8.1 billion in 2019.[29]

Etymology and definition

In common usage, the word "human" generally refers to the only extant species of the genus Homo—anatomically and behaviorally modern Homo sapiens.

In scientific terms, the meanings of "

The English adjective human is a Middle English loanword from Old French humain, ultimately from Latin hūmānus, the adjective form of homō "man." The word's use as a noun (with a plural: humans) dates to the 16th century.[30] The native English term man can refer to the species generally (a synonym for humanity) as well as to human males, or individuals of either sex (though this latter form is less common in contemporary English).[31]

The species

History

million years ago ) |

Evolution and range

The genus Homo evolved and diverged from other hominins in Africa, after the human clade split from the chimpanzee lineage of the hominids (great apes) branch of the primates. Modern humans, defined as the species Homo sapiens or specifically to the single extant subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Eurasia 125,000–60,000 years ago,[35][36] Australia around 40,000 years ago, the Americas around 15,000 years ago, and remote islands such as Hawaii, Easter Island, Madagascar, and New Zealand between the years 300 and 1280.[37][38]

Evidence from molecular biology

The closest living relatives of humans are chimpanzees (genus

Evidence from the fossil record

There is little fossil evidence for the divergence of the gorilla, chimpanzee and hominin lineages.

The earliest members of the genus Homo are

Anatomical adaptations

Human evolution is characterized by a number of

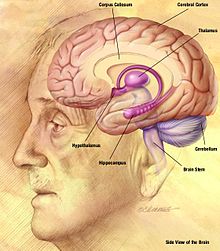

The human species developed a much larger brain than that of other primates—typically 1,330 cm3 (81 cu in) in modern humans, over twice the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla.

The reduced degree of sexual dimorphism is primarily visible in the reduction of the male

Rise of Homo sapiens

By the beginning of the

As early Homo sapiens dispersed, it encountered varieties ofThe "out of Africa" migration of Homo sapiens took place in at least two waves, the first around 130,000 to 100,000 years ago, the second (Southern Dispersal) around 70,000 to 50,000 years ago,[80][81][82] resulting in the colonization of Australia around 65-50,000 years ago,[83][84][85] This recent out of Africa migration derived from East African populations, which had become separated from populations migrating to Southern, Central and Western Africa at least 100,000 years earlier.[86] Modern humans subsequently spread globally, replacing archaic humans (either through competition or hybridization). They inhabited Eurasia and Oceania by 40,000 years ago, and the Americas at least 14,500 years ago.[87][88]

Transition to modernity

Until about 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the

The Neolithic Revolution (the invention of agriculture) took place beginning about 10,000 years ago, first in the Fertile Crescent, spreading through large parts of the Old World over the following millennia, and independently in Mesoamerica about 6,000 years ago. Access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent human settlements, the domestication of animals and the use of metal tools for the first time in history.

Agriculture and sedentary lifestyle led to the emergence of early

Few human populations progressed to

The

With the advent of the

Habitat and population

Early human settlements were dependent on proximity to

Technology has allowed humans to colonize six of the

Human habitation within closed ecological systems in hostile environments, such as Antarctica and outer space, is expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Life in space has been very sporadic, with no more than thirteen humans in space at any given time.[102] Between 1969 and 1972, two humans at a time spent brief intervals on the Moon. As of June 2024, no other celestial body has been visited by humans, although there has been a continuous human presence in space since the launch of the initial crew to inhabit the International Space Station on 31 October 2000.[103] However, other celestial bodies have been visited by human-made objects.[104][105][106]

Since 1800, the human population has increased from one billion[107] to over seven billion.[108] The combined biomass of the carbon of all the humans on Earth in 2018 was estimated at ~ 60 million tons, about 10 times larger than that of all non-domesticated mammals.[109]

In 2004, some 2.5 billion out of 6.3 billion people (39.7%) lived in urban areas. In February 2008, the U.N. estimated that half the world's population would live in urban areas by the end of the year.[110] Problems for humans living in cities include various forms of pollution and crime,[111] especially in inner city and suburban slums. Both overall population numbers and the proportion residing in cities are expected to increase significantly in the coming decades.[112]

Humans have had a dramatic effect on the

Biology

Anatomy and physiology

Most aspects of human physiology are closely

Humans, like most of the other

As a consequence of bipedalism, human females have narrower

Apart from bipedalism, humans differ from chimpanzees mostly in

It is estimated that the worldwide average

Although humans appear hairless compared to other primates, with notable hair growth occurring chiefly on the top of the head,

The

Genetics

Like all mammals, humans are a diploid eukaryotic species. Each somatic cell has two sets of 23 chromosomes, each set received from one parent; gametes have only one set of chromosomes, which is a mixture of the two parental sets. Among the 23 pairs of chromosomes there are 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. Like other mammals, humans have an XY sex-determination system, so that females have the sex chromosomes XX and males have XY.[131]

A rough and incomplete

By comparing the parts of the genome that are not under natural selection and which therefore accumulate mutations at a fairly steady rate, it is possible to reconstruct a genetic tree incorporating the entire human species since the last shared ancestor. Each time a certain mutation (SNP) appears in an individual and is passed on to his or her descendants, a

Human accelerated regions, first described in August 2006,[140][141] are a set of 49 segments of the human genome that are conserved throughout vertebrate evolution but are strikingly different in humans. They are named according to their degree of difference between humans and their nearest animal relative (chimpanzees) (HAR1 showing the largest degree of human-chimpanzee differences). Found by scanning through genomic databases of multiple species, some of these highly mutated areas may contribute to human-specific traits.[citation needed]

The forces of natural selection have continued to operate on human populations, with evidence that certain regions of the genome display directional selection in the past 15,000 years.[142]

Life cycle

As with other mammals,

The zygote divides inside the female's uterus to become an embryo, which over a period of 38 weeks (9 months) of gestation becomes a fetus. After this span of time, the fully grown fetus is birthed from the woman's body and breathes independently as an infant for the first time. At this point, most modern cultures recognize the baby as a person entitled to the full protection of the law, though some jurisdictions extend various levels of personhood earlier to human fetuses while they remain in the uterus.

Compared with other species, human childbirth is dangerous. Painful labors lasting 24 hours or more are not uncommon and sometimes lead to the death of the mother, the child or both.

In developed countries, infants are typically 3–4 kg (7–9 lb) in weight and 50–60 cm (20–24 in) in height at birth.

Evidence-based studies indicate that the life span of an individual depends on two major factors,

Diet

Until the development of agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago, Homo sapiens employed a hunter-gatherer method as their sole means of food collection. This involved combining stationary food sources (such as fruits, grains, tubers, and mushrooms, insect larvae and aquatic mollusks) with

In general, humans can survive for two to eight weeks without food, depending on stored body fat. Survival without water is usually limited to three or four days. About 36 million humans die every year from causes directly or indirectly related to starvation.

Biological variation

No two humans—not even

Most current

The human body's ability to

There is biological variation in the human species—with traits such as

The hue of human skin and hair is determined by the presence of

Structure of variation

Within the human species, the greatest degree of genetic

Males typically have larger

Humans of the same sex are 99.9% genetically identical. There is extremely little variation between human geographical populations, and most of the variation that does occur is at the personal level within local areas, and not between populations.[179][210][211] Of the 0.1% of human genetic differentiation, 85% exists within any randomly chosen local population, be they Italians, Koreans, or Kurds. Two randomly chosen Koreans may be genetically as different as a Korean and an Italian. Any ethnic group contains 85% of the human genetic diversity of the world. Genetic data shows that no matter how population groups are defined, two people from the same population group are about as different from each other as two people from any two different population groups.[179][212][213][214]

Current genetic research has demonstrated that humans on the

Geographical distribution of human variation is complex and constantly shifts through time which reflects complicated human evolutionary history. Most human biological variation is clinally distributed and blends gradually from one area to the next. Groups of people around the world have different frequencies of polymorphic genes. Furthermore, different traits are non-concordant and each have different clinal distribution. Adaptability varies both from person to person and from population to population. The most efficient adaptive responses are found in geographical populations where the environmental stimuli are the strongest (e.g. Tibetans are highly adapted to high altitudes). The clinal geographic genetic variation is further complicated by the migration and mixing between human populations which has been occurring since prehistoric times.[179][218][219][220][221][222]

Human variation is highly non-concordant: most of the genes do not cluster together and are not inherited together. Skin and hair color are not correlated to height, weight, or athletic ability. Human species do not share the same patterns of variation through geography. Skin color varies with latitude and certain people are tall or have brown hair. There is a statistical correlation between particular features in a population, but different features are not expressed or inherited together. Thus, genes which code for superficial physical traits—such as skin color, hair color, or height—represent a minuscule and insignificant portion of the human genome and do not correlate with genetic affinity. Dark-skinned populations that are found in Africa, Australia, and South Asia are not closely related to each other.

Due to practices of group

Psychology

The human brain, the focal point of the

Generally regarded as more capable of these higher order activities, the human brain is believed to be more "intelligent" in general than that of any other known species. While some non-human species are capable of creating structures and

Sleep and dreaming

Humans are generally

Consciousness and thought

Humans are one of the relatively few species to have sufficient self-awareness to recognize themselves in a mirror.[239] Around 18 months most human children are aware that the mirror image is not another person.[240]

The human brain

The physical aspects of the mind and brain, and by extension of the nervous system, are studied in the field of neurology, the more behavioral in the field of psychology, and a sometimes loosely defined area between in the field of psychiatry, which treats mental illness and behavioral disorders. Psychology does not necessarily refer to the brain or nervous system, and can be framed purely in terms of phenomenological or information processing theories of the mind. Increasingly, however, an understanding of brain functions is being included in psychological theory and practice, particularly in areas such as artificial intelligence, neuropsychology, and cognitive neuroscience.

The nature of thought is central to psychology and related fields.

Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is experience itself, and access consciousness, which is the processing of the things in experience.

Motivation and emotion

Motivation is the driving force of desire behind all deliberate

Happiness, or the state of being happy, is a human emotional condition. The definition of happiness is a common philosophical topic. Some people might define it as the best condition that a human can have—a condition of

Emotion has a significant influence on, or can even be said to control, human behavior, though historically many cultures and philosophers have for various reasons discouraged allowing this influence to go unchecked. Emotional experiences perceived as

In modern scientific thought, certain refined emotions are considered a complex neural trait innate in a variety of

Sexuality and love

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2020) |

For humans, sexuality has important social functions: it creates physical intimacy, bonds and hierarchies among individuals, besides ensuring biological

Human choices in acting on sexuality are commonly influenced by social norms which vary between cultures. Restrictions are often determined by religious beliefs or social customs. People can fall anywhere along a continuous scale of sexual orientation.[243] There is considerably more evidence supporting nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation than social ones, especially for males.[244] Recent research, including neurology and genetics, suggests that other aspects of human sexuality are biologically influenced as well.[245]

Behavior

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

| Human society statistics | |

|---|---|

| World population[29] | 8.1 billion |

| Population density[29][246] | 16/km2 (41/sq mi) by total area 54/km2 (141/sq mi) by land area |

Largest cities[247]

|

|

| Most widely spoken native languages[248] | |

| Most popular religions[249] | Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism |

| GDP (nominal) [citation needed] |

US$ 36,356,240 million (US$5,797 per capita) |

| GDP (PPP) [citation needed] |

$51,656,251 million IND ($8,236 per capita) |

Humans are highly social beings and tend to live in large complex social groups. More than any other creature, humans are capable of using systems of communication for self-expression, the exchange of ideas, and

Culture is defined here as patterns of complex symbolic behavior, i.e. all behavior that is not innate but which has to be learned through social interaction with others; such as the use of distinctive

Language

While many species communicate, language is unique to humans, a defining feature of humanity, and a cultural universal. Unlike the limited systems of other animals, human language is open—an infinite number of meanings can be produced by combining a limited number of symbols. Human language also has the capacity of displacement, using words to represent things and happenings that are not presently or locally occurring, but reside in the shared imagination of interlocutors.[130] Language differs from other forms of communication in that it is modality independent; the same meanings can be conveyed through different media, auditively in speech, visually by sign language or writing, and even through tactile media such as braille. Language is central to the communication between humans, and to the sense of identity that unites nations, cultures and ethnic groups. The invention of writing systems at least five thousand years ago allowed the preservation of language on material objects, and was a major technological advancement. The science of linguistics describes the structure and function of language and the relationship between languages. There are approximately six thousand different languages currently in use, including sign languages, and many thousands more that are extinct.[250]

Gender roles

The sexual division of humans into male, female, and in some societies other genders

Kinship

All human societies organize, recognize and classify types of social relationships based on relations between parents and children (

Ethnicity

Humans often form ethnic groups, such groups tend to be larger than kinship networks and be organized around a common identity defined variously in terms of shared ancestry and history, shared cultural norms and language, or shared biological phenotype. Such ideologies of shared characteristics are often perpetuated in the form of powerful, compelling narratives that give legitimacy and continuity to the set of shared values. Ethnic groupings often correspond to some level of political organization such as the

Society, government, and politics

Society is the system of organizations and institutions arising from interaction between humans. Within a society people can be divided into different groups according to their income, wealth, power, reputation, etc., but the structure of social stratification and the degree of social mobility differs, especially between modern and traditional societies.[258] A state is an organized political community occupying a definite territory, having an organized government, and possessing internal and external sovereignty. Recognition of the state's claim to independence by other states, enabling it to enter into international agreements, is often important to the establishment of its statehood. The "state" can also be defined in terms of domestic conditions, specifically, as conceptualized by Max Weber, "a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the 'legitimate' use of physical force within a given territory."[259]

Government can be defined as the political means of creating and enforcing laws; typically via a bureaucratic hierarchy. Politics is the process by which decisions are made within groups; this process often involves conflict as well as compromise. Although the term is generally applied to behavior within governments, politics is also observed in all human group interactions, including corporate, academic, and religious institutions. Many different political systems exist, as do many different ways of understanding them, and many definitions overlap. Examples of governments include monarchy, Communist state, military dictatorship, theocracy, and liberal democracy, the last of which is considered dominant today. All of these issues have a direct relationship with economics.

Trade and economics

Trade is the voluntary exchange of goods and services, and is a form of

Economics is a social science which studies the production, distribution, trade, and consumption of goods and services. Economics focuses on measurable variables, and is broadly divided into two main branches: microeconomics, which deals with individual agents, such as households and businesses, and macroeconomics, which considers the economy as a whole, in which case it considers aggregate supply and demand for money, capital and commodities. Aspects receiving particular attention in economics are resource allocation, production, distribution, trade, and competition. Economic logic is increasingly applied to any problem that involves choice under scarcity or determining economic value.

War

War is a state of organized armed conflict between

There have been a wide variety of

Material culture and technology

Stone tools were used by proto-humans at least 2.5 million years ago.[261] The controlled use of fire began around 1.5 million years ago. Since then, humans have made major advances, developing complex technology to create tools to aid their lives and allowing for other advancements in culture. Major leaps in technology include the discovery of agriculture—what is known as the Neolithic Revolution, and the invention of automated machines in the Industrial Revolution.

Body culture

Throughout history, humans have altered their appearance by wearing clothing[262] and adornments, by trimming or shaving hair or by means of body modifications.

Body modification is the deliberate altering of the

Philosophy and self-reflection

Philosophy is a discipline or field of study involving the investigation, analysis, and development of ideas at a general, abstract, or fundamental level. It is the discipline searching for a general understanding of reality, reasoning and values. Major fields of philosophy include logic, metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of mind, and axiology (which includes ethics and aesthetics). Philosophy covers a very wide range of approaches, and is used to refer to a worldview, to a perspective on an issue, or to the positions argued for by a particular philosopher or school of philosophy.

Religion and spirituality

Religion is generally defined as a

Although the exact level of religiosity can be hard to measure,

Art, music, and literature

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) |

Humans have been producing

Music is a natural

Science

Another unique aspect of human culture and thought is the development of complex methods for acquiring knowledge through observation, quantification, and verification.[citation needed] The scientific method has been developed to acquire knowledge of the physical world and the rules, processes and principles of which it consists, and combined with mathematics it enables the prediction of complex patterns of causality and consequence.[citation needed] An understanding of mathematics is unique to humans, although other species of animal have some numerical cognition.[269]

All of science can be divided into three major branches, the

See also

References

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- PMID 2109087.

- ^ "Hominidae Classification". Animal Diversity Web @ UMich. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- .

- ^ PMID 30007846.

- EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- PMID 30894612.

- ^ Sloat, Sarah (4 January 2018). "Everything We Learned in One Year About Thousands of Years of Human Evolution". Inverse. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018.

- .

- .

- PMID 28552208.

- PMID 15716951.

- PMID 27127403.

- PMID 11786608.

- doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 11102266.

- ^ doi:10.1086/377665.

- PMID 19679810

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 29545508.

- ^ a b Yong, Ed (15 March 2018). "A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity - New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species". The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ PMID 24236011.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3.

- ISSN 2375-2548.

- ISBN 9780521179447

- ^ "Hunting and gathering culture" Archived 16 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica (online). Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016.

- ^ "Neolithic Archived 17 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited. 2014.

- ^ a b c "File POP/1-1: Total population (both sexes combined) by major area, region and country, annually for 1950-2100: Medium fertility variant, 2015–2100". World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Population Estimates and Projections Section. July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- s.v."human."

- ^ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Man, "Definition 2" Archived 22 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 14 September 2017

- JSTOR 4065043.

- from the original on 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Homo sapiens Etymology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Paul Rincon Humans 'left Africa much earlier' Archived 9 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 27 January 2011

- ^ Lowe, David J. (2008). "Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and the impacts of volcanism on early Maori society: an update" (PDF). University of Waikato. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- PMID 22552074.

- ^ PMID 10999270.

- ^ Ajit, Varki and David L. Nelson. 2007. "Genomic Comparisons of Humans and Chimpanzees". Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2007. 36: 191–209: "Sequence differences from the human genome were confirmed to be ∼1% in areas that can be precisely aligned, representing ∼35 million single base-pair differences. Some 45 million nucleotides of insertions and deletions unique to each lineage were also discovered, making the actual difference between the two genomes ∼4%."

- ^ Ken Sayers, Mary Ann Raghanti, and C. Owen Lovejoy. 2012 (forthcoming, october) Human Evolution and the Chimpanzee Referential Doctrine. Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 41

- .

- PMID 9066793.

- ^ Human Chromosome 2 is a fusion of two ancestral chromosomes Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Alec MacAndrew; accessed 18 May 2006.

- .

- PMID 22307721.

- .

- PMID 25739410.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (4 March 2015). "'First human' discovered in Ethiopia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015.

- PMID 25993961.

- PMID 27298468.

- PMID 12802332.

- . Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- PMID 28593953.

- from the original on 4 September 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-393-97854-4.

- ISBN 9780804717465. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016.)

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help - PMID 12110880.

- PMID 25901308.

- ^ .

- ^ H. neanderthalensis is a widely known but poorly understood hominid ancestor Archived 8 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Archaeologyinfo.com. Retrieved on 24 May 2014.

- PMID 17327801.

- PMID 17680251.

- .

- PMID 17439362.

- ^ "Meat-eating was essential for human evolution, says UC Berkeley anthropologist specializing in diet". Berkeley.edu. 14 June 1999. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Meat in the human diet: an anthropological perspective". Thefreelibrary.com. 1 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Dunbar, Robin I.M. (1998). "The Social Brain Hypothesis" (PDF). Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- PMID 11786608.

- doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19679810

- .

- PMID 21357228.

- PMID 20376137.

- PMID 21944045. Hebsgaard MB, Wiuf C, Gilbert MT, Glenner H, Willerslev E (2007). "Evaluating Neanderthal genetics and phylogeny". J. Mol. Evol. 64 (1): 50–60.PMID 17146600.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (17 March 2016). "Humans Interbred With Hominins on Multiple Occasions, Study Finds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- .

- PMID 26853362.

- PMID 25770088.

- PMID 31196864.

- doi:10.1038/nature22968.). St. Fleu, Nicholas (19 July 2017). "Humans First Arrived in Australia 65,000 Years Ago, Study Suggests". New York Times.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISSN 0312-2417.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - PMID 30082377.

- PMID 1840702.

- ^ Wolman, David (3 April 2008). "Fossil Feces Is Earliest Evidence of N. America Humans". news.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - PMID 8976151.

- ISBN 9781285661537. Retrieved 11 July 2015. Spielvogel, Jackson (1 January 2014). Western Civilization: Volume A: To 1500. Cenpage Learning.ISBN 9781285982991. Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015. Thornton, Bruce (2002). Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization. San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books. pp. 1–14.ISBN 978-1-893554-57-3.

- ^ "Greatest Engineering Achievements of the 20th Century". greatachievements.org. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Regional Population 1750–2050". GeoHive. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Atlas – Worldwide Statistics of Casualties, Massacres, Disasters and Atrocities". Necrometrics.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ "Internet Usage Statistics – The Internet Big Picture". Internet World Stats. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Reuters homepage". Reuters. Retrieved 19 November 2010.[dead link]

- PMID 15459379.

- PMID 16553315.

- ^ "How People Modify the Environment" (PDF). Westerville City School District. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "Natural disasters and the urban poor" (PDF). World Bank. October 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017.

- ^ Gammon, Katharine (22 April 2011). "The 10 purest places on Earth". NBC. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017.

- ^ "Population distribution and density". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- PMID 12481916.

- ^ Nancy Atkinson (26 March 2009). "Soyuz Rockets to Space; 13 Humans Now in Orbit". Universetoday.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Kraft, Rachel (11 December 2010). "JSC celebrates ten years of continuous human presence aboard the International Space Station". JSC Features. Johnson Space Center. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Mission to Mars: Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Rover". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Touchdown! Rosetta's Philae probe lands on comet". European Space Agency. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "NEAR-Shoemaker". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "World's population reaches six billion". BBC News. 5 August 1999. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ "UN population estimates". Population Division, United Nations. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- PMID 29784790.

- ^ Whitehouse, David (19 May 2005). "Half of humanity set to go urban". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017.

- ^ [permanent dead link] Urban, Suburban, and Rural Victimization, 1993–98 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics,. Accessed 29 October 2006

- ^ "World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision". Population Division, United Nations. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ Scientific American (1998). Evolution and General Intelligence: Three hypotheses on the evolution of general intelligence Archived 13 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Climate Change 2001: Working Group I: The Scientific Basis". grida.no/. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ^ American Association for the Advancement of Science. Foreword Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. AAAS Atlas of Population & Environment.

- ^ Wilson, E.O. (2002). The Future of Life.

- ISBN 978-1-4042-3362-1. Length: 32 pages

- ^ "Human Anatomy". Inner Body. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Parker-Pope, Tara (27 October 2009). "The Human Body Is Built for Distance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b c O'Neil, Dennis. "Humans". Primates. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ John, Brenman. "What is the role of sweating glands in balancing body temperature when running a marathon?". Livestrong.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Senior Citizens Do Shrink – Just One of the Body Changes of Aging". News. Senior Journal. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- PMID 14527631.

- ^ "Human weight". Articleworld.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Mass Of An Adult". The Physics Factbook: An Encyclopedia of Scientific Essays. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-59745-400-1. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- PMID 10927998.

- ^ Why Humans and Their Fur Parted Way by Nicholas Wade, New York Times, 19 August 2003.

- ^ Kirchweger, Gina. "The Biology of Skin Color: Black and White". Evolution: Library. PBS. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b Collins, Desmond (1976). The Human Revolution: From Ape to Artist. p. 208.

- ISBN 978-1-4684-0109-7.

- PMID 20441615.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 9465125.

- PMID 9096352.

- PMID 15508000.

- PMID 15507999.

- )

- PMID 19500773. University of Leeds – New 'molecular clock' aids dating of human migration history Archived 20 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 23908239.

- PMID 16915236.

- PMID 17040131.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ Wade, Nicholas (7 March 2007). "Still Evolving, Human Genes Tell New Story". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- developed countries.

- PMID 8579191.

- PMID 16130838.

- from the original on 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Low Birthweight". Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- PMID 15024783.

- ISBN 978-0-385-46792-6.

- ISBN 978-0-465-03127-6.

- .

- ^ Marziali, Carl (7 December 2010). "Reaching Toward the Fountain of Youth". USC Trojan Family Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Kalben, Barbara Blatt (2002). "Why Men Die Younger: Causes of Mortality Differences by Sex". Society of Actuaries. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook – World entry". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2006," Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine United Nations Development Programme, pp. 363–66, 9 November 2006

- ^ The World Factbook Archived 12 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 April 2005.

- ^ "U.N. Statistics on Population Ageing". United Nations. 28 February 2002. Archived from the original on 8 December 2005. Retrieved 2 April 2005.

- ISBN 978-3-642-11519-6. Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2016.

- PMID 2697806.

- pongidsapproximately 7 million years ago, the available evidence shows that all species of hominins ate an omnivorous diet composed of minimally processed, wild-plant, and animal foods.

- PMID 12778049.

- PMID 15699220.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - PMID 12691181.

- ^ Earliest agriculture in the Americas Archived 3 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Earliest cultivation of barley Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Earliest cultivation of figs Archived 2 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 19 February 2007

- PMID 19656837.

- PMID 9299882.

- ^ United Nations Information Service. "Independent Expert On Effects Of Structural Adjustment, Special Rapporteur On Right To Food Present Reports: Commission Continues General Debate On Economic, Social And Cultural Rights" Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations, 29 March 2004, p. 6. "Around 36 million people died from hunger directly or indirectly every year.".

- PMID 9164317.

- ^ PMID 16198769.

- PMID 19700042.

- PMID 6007033.

- PMID 8741866.

- PMID 16826514.

- PMID 16175499.

- ^ Dr. Shafer, Aaron. "Understanding Genetics". The Tech. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

The DNA sequence in your genes is on average 99.9% identical to ANY other human being.

- ^ "Genetic – Understanding Human Genetic Variation". Human Genetic Variation. National Institute of Health (NIH). Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

Between any two humans, the amount of genetic variation—biochemical individuality—is about 0.1%.

- ^ "Human Diversity – Go Deeper". Power of an Illusion. PBS. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Chimps show much greater genetic diversity than humans". Media. University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Roberts, Dorothy (2011). Fatal Invention. London, New York: The New Press.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. "Human Biological Adaptability; Overview". Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. "Adapting to Climate Extremes". Human Biological Adaptability. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- PMID 15463992.

- PMID 21427751.

- PMID 18410566.

- PMID 14634648.

- .

- doi:10.1086/381006.

- ^ Jablonski, N.G. & Chaplin, G. (2000). "The evolution of human skin coloration" Archived 14 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine (pdf), Journal of Human Evolution 39: 57–106.

- PMID 10733465.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ Robin, Ashley (1991). Biological Perspectives on Human Pigmentation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Muehlenbein, Michael (2010). Human Evolutionary Biology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–213.

- ^ "Journey of Mankind". Peopling of the World. Bradshaw Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Birke, Lydia. The Gender and Science Reader ed. Muriel Lederman and Ingrid Bartsch. New York, Routledge, 2001. 306–22

- PMID 15454336.

- ISSN 1090-5138, 2006, Volume 27, Issue 4, pp. 283–96

- ^ "Ogden et al (2004). Mean Body Weight, Height, and Body Mass Index, United States 1960–2002 Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, Number 347, October 27, 2004" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "Gender Differences in Endurance Performance and Training". Archived from the original on 27 January 2010.

- PMID 8477683.

- ^ "Women nose ahead in smell tests". BBC News. 4 February 2002. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Study Reveals Reason Women Are More Sensitive To Pain Than Men". Sciencedaily.com. 25 October 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ Gender, women, and health Archived 25 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Reports from WHO 2002–2005

- ^ OCLC 7831448.

- ISBN 978-0-87795-484-2.

- )

- ISBN 978-0-316-81236-8.

- ^ M. McLaughlin; T. Shryer (8 August 1988). "Men vs women: the new debate over sex differences". U.S. News & World Report: 50–58.

- PMID 6259728.

- ISBN 978-0-19-510357-1.

- ISBN 978-0-06-170780-3.

- ^ "The Science Behind the Human Genome Project". Human Genome Project. US Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

Almost all (99.9%) nucleotide bases are exactly the same in all people.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. "Ethnicity and Race: Overview". Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Genetic – Understanding Human Genetic Variation". Human Genetic Variation. National Institute of Health (NIH). Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

In fact, research results consistently demonstrate that about 85 percent of all human genetic variation exists within human populations, whereas about only 15 percent of variation exists between populations.

- ^ a b Goodman, Alan. "Interview with Alan Goodman". Race Power of and Illusion. PBS. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Marks, J. (2010) Ten facts about human variation. In: Human Evolutionary Biology, edited by M. Muehlenbein. New York: Cambridge University Press "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - PMID 10712212.

- ^

"New Research Proves Single Origin Of Humans In Africa". Science Daily. 19 July 2007. Archivedfrom the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^

Manica, A; Amos, W; Balloux, F; Hanihara, T (2007). "The effect of ancient population bottlenecks on human phenotypic variation". PMID 17637668.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. "Adapting to High Altitude". Human Biological Adaptability. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. "Overview". Human Biological Adaptability. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b O'Neil, Dennis. "Models of Classification". Modern Human Variation. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Marks, Jonathan. "Interview with Jonathan Marks". Race – The Power of an Illusion. PBS. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b Goodman, Alan. "Background Readings". Race – Power of an Illusion. PBS. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- .

genetic evidence [demonstrate] that strong levels of natural selection acted about 1.2 mya to produce darkly pigmented skin in early members of the genus Homo

- PMID 1554510.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. "Overview". Modern Human Variation. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ISBN 0-226-48688-5.

- ^ Iqbal, Saadia. "A New Light on Skin Color". National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ PMID 15507998.

- PMID 10655044.

That race (...) is not a scientific term is generally agreed upon by scientists—and a message that cannot be repeated often enough.

- ^ Harrison, Guy (2010). Race and Reality. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

Race is a poor empirical description of the patterns of difference that we encounter within our species. The billions of humans alive today simply do not fit into neat and tidy biological boxes called races. Science has proven this conclusively. The concept of race (...) is not scientific and goes against what is known about our ever-changing and complex biological diversity.

- ^ Roberts, Dorothy (2011). Fatal Invention. London, New York: The New Press.

The genetic differences that exist among populations are characterized by gradual changes across geographic regions, not sharp, categorical distinctions. Groups of people across the globe have varying frequencies of polymorphic genes, which are genes with any of several differing nucleotide sequences. There is no such thing as a set of genes that belongs exclusively to one group and not to another. The clinal, gradually changing nature of geographic genetic difference is complicated further by the migration and mixing that human groups have engaged in since prehistory. Genetic studies have substantiated the absence of clear biological borders; thus the term "race" is rarely used in scientific terminology, either in biological anthropology and in human genetics. Race has no genetic or biological basis. Human beings do not fit the zoological definition of race. Race is not a biological category that is politically charged. It is a political category that has been disguised as a biological one.

- ^ Goodman, Alan. "Interview with Alan Goodman". Race Power of and Illusion. PBS. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

There's no biological basis for race. And that is in the facts of biology, the facts of non-concordance, the facts of continuous variation, the recentness of our evolution, the way that we all commingle and come together, and how genes flow. (...) There's no generalizability to race. There is no center there (...). It's fluid.

- ^ Steve Olson, Mapping Human History: Discovering the Past Through Our Genes, Boston, 2002

- ^ "Race – The Power of an Illusion". PBS. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- .

- .

- ^ 3-D Brain Anatomy Archived 5 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Secret Life of the Brain, Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 3 April 2005.

- PMID 19896872.

- ISBN 978-0-08-054263-8. Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Jack Palmer. "Consciousness and the Symbolic Universe". Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- ^ Intelligence test at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Ned Block: On a Confusion about a Function of Consciousness in: The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1995.

- ^ "Sexual orientation, homosexuality and bisexuality". American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- PMID 27113562.

- ISBN 978-0-465-00802-5.

- CIA. 17 May 2016. Archivedfrom the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "The World's Cities in 2016" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-3388-1.

- ^ "A Map of Gender-Diverse Cultures | Independent Lens". PBS. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ J. Hutchinson & A.D. Smith (eds.), Oxford readers: Ethnicity (Oxford 1996), "Introduction"[page needed]

- ^ Smith, Anthony D. (1999) Myths and Memories of the Nation. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–7

- .

- ISBN 1412901014p. 171

- ^ Ronald Cohen 1978 "Ethnicity: Problem and Focus in Anthropology" in Annual Review of Anthropology 7: 383 Palo Alto: Stanford University Press

- ^ Thomas Hylland Eriksen (1993) Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Pluto Press[page needed]

- ^ Schizzerotto, Antonio. "Social Stratification" (PDF). University of Trento. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Max Weber's definition of the modern state 1918, by Max Weber, 1918. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- ^ Ferguson, Niall. "The Next War of the World." Foreign Affairs, Sep/Oct 2006

- PMID 8009220.

- PMID 19745144.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9. Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Evolutionary Religious Studies: A New Field of Scientific Inquiry". Archived from the original on 17 August 2009.

- PMID 18948934.

- PMID 12171998.

- PMID 19105008.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (12 September 2018). "Oldest Known Drawing by Human Hands Discovered in South African Cave". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Mary C. Olmstead & Valerie A. Kuhlmeier, Comparative Cognition (Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 209-10.

- ^ "Branches of Science" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2017.

- ^ "Science and Pseudo-Science". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2017. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

Further reading

- Freeman, Scott; Jon C. Herron (2007). Evolutionary Analysis (4th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 0-13-227584-8. pp. 757–61.

- Reich, David (2018). Who We Are And How We Got Here – Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. ISBN 978-1101870327.

External links

- Archaeology Info

- Homo sapiens – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- "Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- View the human genome on Ensembl

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Media related to Homo sapiens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Homo sapiens at Wikimedia Commons