Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy

| Timelines of World War II |

|---|

| Chronological |

| Prelude |

| By topic |

| By theatre |

In

Some countries' leaders cooperated with Italy and Germany because they wanted to

Axis military forces recruited many volunteers, sometimes at gunpoint, more often with promises that they later broke, or from among POWs trying to escape appalling and frequently lethal conditions in their detention camps. Other volunteers willingly enlisted because they shared Nazi or fascist ideologies.

Terminology

Collaboration in Western Europe

Belgium

Belgium was invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940[5] and occupied until the end of 1944.

Political collaboration took separate forms across the Belgian language divide. In Dutch-speaking Flanders, the Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond (Flemish National Union or VNV), clearly authoritarian, anti-democratic and influenced by fascist ideas,[6] became a major player in the German occupation strategy as part of the pre-war Flemish Movement. VNV politicians were promoted to positions in the Belgian civil administration.[7] VNV and its comparatively moderate stance was increasingly eclipsed later in the war by the more radical and pro-German DeVlag movement.[8]

In French-speaking Wallonia, Léon Degrelle's Rexist Party, a pre-war authoritarian and Catholic Fascist political party,[9] became the VNV's Walloon equivalent, although Rex's Belgian nationalism put it at odds with the Flemish nationalism of VNV and the German Flamenpolitik. Rex became increasingly radical after 1941 and declared itself part of the Waffen-SS.

Although the pre-war Belgian government went into exile in 1940, the Belgian civil service remained in place for much of the occupation. The Committee of Secretaries-General, an administrative panel of civil servants, although conceived as a purely technocratic institution, has been accused of helping to implement German occupation policies. Despite its intention of mitigating harm to Belgians, it enabled but could not moderate German policies such as the persecution of Jews and deportation of workers to Germany. It did manage to delay the latter to October 1942.[10] Encouraging the Germans to delegate tasks to the Committee made their implementation much more efficient than the Germans could have achieved by force.[11] Belgium depended on Germany for food imports, so the committee was always at a disadvantage in negotiations.[11]

The Belgian government in exile criticized the committee for helping the Germans.[12][13] The Secretaries-General were also unpopular in Belgium itself. In 1942, journalist Paul Struye described them as "the object of growing and almost unanimous unpopularity."[14] As the face of the German occupation authority, they became unpopular with the public, which blamed them for the German demands they implemented.[12]

After the war, several of the Secretaries-General were tried for collaboration. Most were quickly acquitted.

Belgian police have also been accused of collaborating, especially in the Holocaust.[8]

Towards the end of the war, militias of collaborationist parties actively carried out reprisals for resistance attacks or even assassinations.[18] Those assassinations included leading figures suspected of resistance involvement or sympathy,[19] such as Alexandre Galopin, head of the Société Générale, assassinated in February 1944. Among the retaliatory massacres of civilians[18] were the Courcelles massacre, in which 20 civilians were killed by the Rexist paramilitary for the assassination of a Burgomaster, and a massacre at Meensel-Kiezegem, where 67 were killed.[20]

British Channel Islands

The Channel Islands were the only British territory in Europe occupied by Nazi Germany. The policy of the islands' governments was what they called "correct relations" with the German occupiers. There was no armed or violent resistance by islanders to the occupation.[21] After 1945 allegations of collaboration were investigated.[clarification needed] In November 1946, the UK Home Secretary informed the UK House of Commons[22] that most allegations lacked substance. Only twelve cases of collaboration were considered for prosecution, and the Director of Public Prosecutions ruled them out for insufficient grounds. In particular, it was decided that there were no legal grounds for proceeding against those alleged to have informed the occupying authorities against their fellow citizens.[23][page needed]

On the islands of Jersey and Guernsey, laws[24][25] were passed to retrospectively confiscate the financial gains made by war profiteers and black marketeers.

After liberation, British soldiers had to intervene to prevent revenge attacks on women thought to have fraternized with German soldiers.[26]

Denmark

When on 9 April 1940, German forces invaded

Denmark's government cooperated with the German occupiers until 1943,[30] and helped organize sales of industrial and agricultural products to Germany.[31] The Danish government enacted a number of policies to satisfy Germany and retain the social order. Newspaper articles and news reports "which might jeopardize German-Danish relations" were outlawed[citation needed] and on 25 November 1941, Denmark joined the Anti-Comintern Pact.[32] The Danish government and King Christian X repeatedly discouraged sabotage and encouraged informing on the resistance movement. Resistance fighters were imprisoned or executed; after the war informants were sentenced to death.[33][34][35]

Prior to, during and after the war, Denmark enforced a restrictive refugee policy; it handed over to German authorities at least 21 Jewish refugees who managed to cross the border;[31] 18 of them died in concentration camps, including a woman and her three children.[36] In 2005 prime minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen officially apologized for these policies.[37]

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, German authorities demanded the arrest of Danish communists. The Danish government complied, directing the police to arrest 339 communists listed on secret registers. Of these, 246, including the three communist members of the Danish parliament, were imprisoned in the Horserød camp, in violation of the Danish constitution. On 22 August 1941, the Danish parliament passed the Communist Law, outlawing the Communist Party of Denmark and also communist activities, in another violation of the Danish constitution. In 1943, about half of the imprisoned communists were transferred to Stutthof concentration camp, where 22 of them died.

Industrial production and trade were, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected towards Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark[38] and feared that higher unemployment and poverty could lead to civil unrest, resulting in a crackdown by the Germans.[39] Unemployment benefits could be denied if jobs were available in Germany, so an average of 20,000 Danes worked in German factories through the five years of the war.[40]

The Danish cabinet, however, rejected German demands for legislation discriminating against Denmark's Jewish minority. Demands for a death penalty were likewise rebuffed and so were demands to give German military courts jurisdiction over Danish citizens and for the transfer of Danish army units to the German military.[citation needed]

France

Vichy France

Pierre Laval and other Vichy ministers initially prioritized saving French lives and repatriating French prisoners of war.[43] The illusion of autonomy was important to Vichy, which wanted at costs to avoid direct rule by the German military government.

German authorities implicitly threatened to replace the Vichy administration with unreservedly pro-Nazi leaders such as Marcel Déat, Joseph Darnand and Jacques Doriot, who were permitted to operate, publish and criticise Vichy for insufficiently cooperation with Nazi Germany.

Collaborationist movements

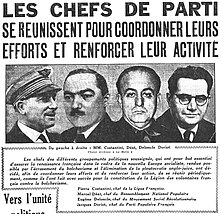

The four main political factions which emerged as leading proponents of radical collaborationism in France were Marcel Déat's

Uniformed collaboration

The collaboration of the French police was decisive for the implementation of the Holocaust in occupied France. Germany used French police to maintain order and repress the resistance. The French police were responsible for the census of Jews, their arrest and their assembly in camps from where they were sent abroad to extermination camps. To do this the police requisitioned buses and used the rail network of SNCF trains.[48] In January 1943, Laval established the Milice, a paramilitary police force led by Joseph Darnand that assisted the Gestapo in fighting the Resistance and persecuting Jews, it counted 30,000 members both male and female.[47]

In July 1941, the collaborationist parties cooperated in organising and recruiting the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (LVF), to fight alongside German forces on the Eastern Front. From July 1941, a total of 5,800 French volunteers served with the LVF until its disbanding in November 1944. In February 1945, French volunteers, either from the LVF or the Milice, were incorporated into the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne, which had a strength of 7,340 men at the time of its deployment in eastern Europe and Berlin.[49] According to French historian Pierre Giolitto about 30,000 Frenchmen served in German military units (including non-combatants), during the course of the war.[47]

Communist party

Until the German invasion of Russia on 21 June 1941, the national leadership of the French Communist Party (PCF) remained close to the line defined by the Comintern and the Soviet Union, claiming that “the only legitimate struggle is the revolutionary struggle and not the pseudo-resistance of the Gaullists, pawns of British capitalism".[50][51] Following this logic, relations with the occupier were ambiguous. Ronald Tiersky has described the actions of the French communists during that period as "actively collaborating in certain respects".[52]

During the early days of the

Following the Wehrmacht invasion of Russia a year later, the PCF completely changed its stance and became one of the key players of the French Resistance.[58][59]

French workers for Germany

Vichy initially agreed, for every repatriated French prisoner-of-war, to send three French volunteers to work in German factories. When this program (known as la relève) didn't draw enough workers to please the Reich, Vichy began in February 1943 to conscript young Frenchmen, ages 18—20 into the Service du travail obligatoire (STO; English: compulsory labour service), a compulsory two-year labour draft that resulted in the deportation to German labor camps of 800,000 Frenchmen.[60]

Very unpopular, the STO provoked growing hostility towards the policy of collaboration and led to a great number of young men joining the French Resistance rather than report for it. People began to disappear into forests and mountain wildernesses to join the maquis (rural Resistance).[61][62]

Vichy collaboration in the Holocaust

Long before the Occupation, France had had a history of native anti-Semitism and

Pierre Laval was an important decision-maker in the extermination of Jews, the

In 1995, President Jacques Chirac officially recognized the responsibility of the French state for the deportation of Jews during the war, in particular, the more than 13,000 victims, of whom only 2,500 survived, of the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942, in which Laval decided, of his own volition, to deport children along with their parents.[65] Bousquet also organized the French police to work with the Gestapo in the massive Marseille roundup (rafle) that decimated a whole neighbourhood in the Old Port.

Estimates of how many of France's Jews (about 300,000 at the start of the Occupation) died in the Holocaust range from about 60,000 (≅ 20%) to about 130,000 (≅ 43%).[66] According to Serge Klarsfeld’s study of the records kept at the Drancy internment camp, out of the 75,721 jews deported from France to death camps in Poland, only 2,567 survived.[47]

Aftermath

As the

As a formal legal order returned to France, the informal purges were replaced by l'Épuration légale (legal purge). The most notable, and most demanded, convictions were those of Pierre Laval, tried and executed in October 1945, and Marshal Philippe Pétain, whose 1945 death sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment on the Bréton Yeu, where he died in 1951.

Several decades later, a few surviving ex-collaborators such as Paul Touvier were tried for crimes against humanity. René Bousquet was rehabilitated and regained some influence in French politics, finance and journalism, but was nonetheless investigated in 1991 for deporting Jews. He was assassinated in 1993 just before his trial would have begun. Maurice Papon served as prefect of the Paris police under President de Gaulle (thus bearing ultimate responsibility for the Paris massacre of 1961) and, 20 years later, as Budget Minister under President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, before Papon's 1998 conviction and imprisonment for crimes against humanity in organizing the deportation of 1,560 Jews from the Bordeaux region to the French internment camp at Drancy.

Other collaborators such as Émile Dewoitine also managed to have important roles after the war. Dewoitine was eventually named head of Aérospatiale, which created the Concorde airplane.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg was invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940 and remained under German occupation until early 1945. Initially, the country was governed as a distinct region as the Germans prepared to assimilate its Germanic population into Germany itself. The Volksdeutsche Bewegung (VdB) was founded in Luxembourg in 1941 under the leadership of Damian Kratzenberg, a German teacher at the Athénée de Luxembourg.[68] It aimed to encourage the population towards a pro-German position, prior to outright annexation, using the slogan Heim ins Reich. In August 1942, Luxembourg was annexed into Nazi Germany, and Luxembourgish men were drafted into the German military.

Monaco

During the Nazi occupation of Monaco, the police arrested and turned over 42 Central European Jewish refugees to the Nazis while also protecting Monaco's own Jews.[69]

Netherlands

The Germans re-organized the pre-war Dutch police and established a new Communal Police, which helped Germans fight the country's resistance and to deport Jews. The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB) had militia units, whose members were transferred to other paramilitaries like the Netherlands Landstorm or the Control Commando. A small number of people greatly assisted the German in their hunt for Jews, including some policemen and the Henneicke Column. Many of them were members of the NSB.[70] The column alone was responsible for the arrest of about 900 Jews.[71][72]

Norway

In Norway, the

About 45,000 Norwegian collaborators joined the fascist party

Nasjonal Samling had very little support among the population at large[75] and Norway was one of few countries where resistance during World War II was widespread before the turning point of the war in 1942–43.[citation needed]

After the war, Quisling was executed by firing squad.

Collaboration in Eastern Europe

Albania

After the Italian invasion of Albania, the Royal Albanian Army, police and gendarmerie were amalgamated into the Italian armed forces in the newly created Italian protectorate of Albania.

The

Baltic states

The three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, first invaded by the Soviet Union, were later occupied by Germany and than again invaded by the Soviets and incorporated, together with the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic of the U.S.S.R. (Belarus, see below), into Reichskommissariat Ostland.[81]

Estonia

Resistance groups were organised by Germans in August 1941 into the

The Germans formed a puppet government, the

Immediately after entering Estonia, the Germans began forming volunteer Estonian units the size of a battalion. By January 1942, six Security Groups (battalions No. 181-186, about 4,000 men) had been formed and were subordinate to the Wehrmacht 18th Army.[94] After the one-year contract expired, some volunteers transferred to the Waffen-SS or returned to civilian life, and three Eastern Battalions (No. 658-660) were formed from those who remained.[94] They fought until early 1944, after which their members transferred to the 20th Waffen-SS Division.[94]

Beginning in September 1941, the SS and police command created four Infantry Defence Battalions (No. 37-40) and a reserve and sapper battalion (No. 41-42), which were operationally subordinate to the Wehrmacht. From 1943 they were called Police Battalions, with 3,000 serving in them.[94] In 1944 they were transformed into two infantry battalions and evacuated to Germany in the fall of 1944, where they were incorporated into the 20th Waffen-SS Division.[94]

In the fall of 1941, the Germans also formed eight police battalions (No. 29-36), of which only Battalion No. 36 had a typically military purpose. However, due to shortages, most of them were sent to the front near Leningrad,[95] and were mostly disbanded in 1943. That same year, the SS and police command created five new Security and Defense Battalions (they inherited No. 29-33 and had more than 2,600 men).[96] In the spring of 1943, five Defence Battalions (No. 286-290) were established as compulsory military service units. The 290th Battalion consisted of Estonian Russians. Battalions No. 286, 288 and 289 were used to fight partisans in Belarus.[97]

On Aug. 28, 1942, the Germans formed the volunteer Estonian Waffen-SS Legion. Of the approximately 1,000 volunteers, 800 were incorporated into Battalion Narva and sent to Ukraine in the spring of 1943.[98] Due to the shrinking number of volunteers, in February 1943 the Germans introduced compulsory conscription in Estonia. Born between 1919 and 1924 faced the choice of going to work in Germany, joining the Waffen-SS or Estonian auxiliary battalions. 5,000 joined the Estonian Waffen-SS Legion, which was reorganized into the 3rd Estonian Waffen-SS Brigade.[97]

As the Red Army advanced, a general mobilization was announced, officially supported by Estonia's last Prime Minister Jüri Uluots. By April 1944, 38,000 Estonians had been drafted. Some went into the 3rd Waffen-SS Brigade, which was enlarged to division size (20th Waffen-SS Division: 10 battalions, more than 15,000 men in the summer of 1944) and also incorporated most of the already existing Estonian units (mostly Eastern Battalions).[99] Younger men were conscripted into other Waffen-SS units. From the rest, six Border Defense Regiments and four Police Fusilier Battalions (Nos. 286, 288, 291, and 292).[100]

The Estonian Security Police and SD,[101] the 286th, 287th and 288th Estonian Auxiliary Police battalions, and 2.5–3% of the Estonian Omakaitse (Home Guard) militia units (between 1,000 and 1,200 men) took part in rounding up, guarding or killing of 400–1,000 Roma and 6,000 Jews in concentration camps in the Pskov region of Russia and the Jägala, Vaivara, Klooga and Lagedi concentration camps in Estonia.

Guarded by these units, 15,000 Soviet POWs died in Estonia: some through neglect and mistreatment and some by execution.[102]

Latvia

Deportations and murders of Latvians by the Soviet

The next day, 2 July, Stahlecker instructed Arājs to have the Arājs Kommandos unleash

The activities of the Einsatzkommando were constrained after the full establishment of the German occupation authority, after which the SS made use of select units of native recruits.[104] German General Wilhelm Ullersperger and Voldemārs Veiss, a well known Latvian nationalist, appealed to the population in a radio address to attack "internal enemies". During the next few months, the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police primarily focused on killing Jews, Communists and Red Army stragglers in Latvia and in neighbouring Byelorussia.[105]

In February–March 1943, eight Latvian battalions took part in the punitive anti-partisan

The creation of the Arājs Kommando was "one of the most significant inventions of the early Holocaust",

Lithuania

Prior to the German invasion, some leaders in Lithuania and in exile believed Germany would grant the country autonomy, as they had the Slovak Republic. The German intelligence service Abwehr believed that it controlled the Lithuanian Activist Front, a pro-German organization based at the Lithuanian embassy in Berlin.[113] Lithuanians formed the Provisional Government of Lithuania on their own initiative, but Germany did not recognize it diplomatically, or allow Lithuanian ambassador Kazys Škirpa to become prime minister, instead actively thwarting his activities. The provisional government disbanded, since it had no power and it had become clear that the Germans came as occupiers not liberators from Soviet occupation, as initially thought. By 1943, the German opinion of Lithuanians was that they had failed to show allegiance to them.[114] When the Germans called-up Lithuanians for military service in spring 1943, Lithuanians protested against it by making the call-up produce dismally low numbers, which angered the German occupiers.[114]

Units under

In 1941, the

In March 1942, in Poland, the

The participation of the local populace was a key factor in the

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was interested in acquiring

Czecho-Slovakia

Sudetenland

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (the Czech lands)

When the Germans annexed Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939, they created the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from the Czech part of pre-war Czechoslovakia[140] It had its own military forces, including a 12-battalion 'government army', police and gendarmerie. Most members of the 'government army' were sent to Northern Italy in 1944 as labourers and guards.[141][unreliable source?] Whether or not the government army was a collaborationist force has been debated. Its commanding officer, Jaroslav Eminger, was tried and acquitted on charges of collaboration following World War II.[142] Some members of the force engaged in active resistance operations while in the army, and, in the waning days of the conflict, elements of the army joined in the Prague uprising.[143]

Slovak Republic

The Slovak Republic (Slovenská Republika) was a quasi-independent ethnic Slovak state which existed from 14 March 1939 to 8 May 1945 as an ally and client state of Nazi Germany. The Slovak Republic existed on roughly the same territory as present-day Slovakia (except for the southern and eastern parts). It bordered Germany, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, German-occupied Poland, and Hungary.

Greece

Germany put a Nazi government in place in Greece. Prime ministers Georgios Tsolakoglou, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos and Ioannis Rallis[144] all cooperated with Axis authorities. Greece exported agricultural products, especially tobacco, to Germany, and Greek "volunteers" worked in German factories.[145]

The collaboration government created armed paramilitary forces such as the

Greek National-Socialist parties like

During the Axis occupation, a number of

An Aromanian political and paramilitary force, the Roman Legion, led by Aromanian nationalists Alcibiades Diamandi and Nicolaos Matussis, also collaborated with Italian forces.[citation needed]

Hungary

In April 1941, in order to regain territory and under German pressure, Hungary allowed the Wehrmacht across its territory in the

Hungary joined the war on April 11, after the proclamation of the Independent State of Croatia.[citation needed]

It is not clear whether the 10,000–20,000 Jewish refugees (from Poland and elsewhere) were counted in the January 1941 census. They, and about 20,000 people who could not prove legal residency since 1850, were deported to southern Poland. According to Nazi German reports, a total of 23,600 Jews were murdered, including 16,000 who had earlier been expelled from Hungary[154] between July 15 and August 12, 1941, and either abandoned there or handed over to the Germans. In practice, the Hungarians deported many people whose families had lived in the area for generations. In some cases, applications for residency permits were allowed to pile up without action by Hungarian officials until after the deportations had been carried out. The vast majority (16,000) of those deported were massacred in the Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre at the end of August.[155][a]

In the massacres in Újvidék (Novi Sad) and nearby villages, 2,550–2,850 Serbs, 700–1,250 Jews and 60–130 others were murdered by the Hungarian Army and "Csendőrség" (gendarmerie) in January 1942. Those responsible, Ferenc Feketehalmy-Czeydner, Márton Zöldy [hu], József Grassy, László Deák and others, were later tried in Budapest in December 1943 and were sentenced, but some escaped to Germany.[citation needed]

During the war, Jews were called up to serve in unarmed "

Following the

Poland

Unlike some other German-occupied European countries,

Shortly after the German

Some of the collaborators – szmalcowniks – blackmailed Jews and their Polish rescuers and acted as informers, turning in Jews and Poles who hid them, and reporting on the Polish resistance.[176] Many prewar Polish citizens of German descent voluntarily declared themselves Volksdeutsche ("ethnic Germans"), and some of them committed atrocities against the Polish population and organized large-scale looting of property.[177][178]

The Germans set up Jewish-run governing bodies in Jewish communities and

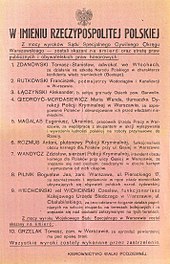

The Polish Underground State's wartime underground courts investigated 17,000 Poles who collaborated with the Germans; about 3,500 were sentenced to death.[180][181]

Romania

- See also Porajmos#Persecution in other Axis countries.

According to an international commission report released by the Romanian government in 2004, between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews died on Romanian soil, in the war zones of Bessarabia, Bukovina, and in territories formerly occupied by Soviets that came under Romanian control (Transnistria Governorate). Of the 25,000 Romani deported to concentration camps in Transnistria, 11,000 died.[182]

Though much of the killing was committed in the war zone by Romanian and German troops, in the

Half of the estimated 270,000 to 320,000 Jews living in Bessarabia, Bukovina, and

Romanian soldiers and gendarmes also worked with the Einsatzkommandos, German killing squads, tasked with massacring Jews and Roma in conquered territories, the local Ukrainian militia, and the SS squads of local Ukrainian Germans (Sonderkommando Russland and Selbstschutz). Romanian troops were in large part responsible for the 1941 Odessa massacre, in which from October 18, 1941, to mid-March 1942 Romanian soldiers, gendarmes and police, killed up to 25,000 Jews and deported more than 35,000.[182]

The lowest respectable mortality estimates run to about 250,000 Jews and 11,000 Roma in these eastern regions.[citation needed]

Nonetheless, half of the Jews living within the pre-Barbarossa borders survived the war, although they were subject to a wide range of harsh conditions, including forced labor, financial penalties, and discriminatory laws. All Jewish property was nationalized.

A report commissioned and accepted by the Romanian government in 2004 on the Holocaust concluded:[182]

Of all the allies of Nazi Germany, Romania bears responsibility for the deaths of more Jews than any country other than Germany itself. The murders committed in Iasi, Odessa, Bogdanovka, Domanovka, and Peciora, for example, were among the most hideous murders committed against Jews anywhere during the Holocaust. Romania committed genocide against the Jews. The survival of Jews in some parts of the country does not alter this reality.

Yugoslavia

On 25 March 1941, under considerable pressure, the Yugoslav government agreed to the signing of the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany, guaranteeing Yugoslavia's neutrality. The agreement was extremely unpopular in Serbia and led to massive street demonstrations.[186] Two days later, on 27 March, Serb military officers led by general Dušan Simović overthrew the regency and placed 17-year-old King Peter on the throne.[187] Furious at the temerity of the Serbs, Hitler ordered the invasion of Yugoslavia.[188] On 6 April 1941, without a declaration of war, combined German and Italian military armies invaded. Eleven days later Yugoslavia capitulated and was subsequently partitioned among the Axis states.[189]

The

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia

Under German military occupation Serbia was at first directly administered by Nazis, then by a

Serbian units

Serbian collaborationist organizations the Serbian State Guard (SDS) and the Serbian Border Guard (SGS) reached a combined 21,000 men at their peak. The Serbian Volunteers Corps (SDK), the party militia of the fascist Yugoslav National Movement led by Dimitrije Ljotić, reached 9,886 men; its members helped guard and run concentration camps and fought the Yugoslav Partisans and the Chetniks alongside the Germans. In October 1941, the Serbian Volunteer Corps participated in the Kragujevac massacre, arresting and delivering hostages to the Wehrmacht.[195] The members of the Serbian Volunteer Corps had to take an oath stating that they would fight to death against both Communists and Chetniks.[193]

Collaborationist Belgrade Special Police helped German units round up Jewish citizens for deportation to concentration camps. By the summer of 1942, most Serbian Jews had been exterminated.[196] By the end of 1942 the Special Police had 240 agents and 878 police guards under the command of the Gestapo.[194] After the liberation of the country in October 1944, the collaborationist forces retreated with the German army and were later absorbed into the Waffen-SS.[197]

Almost from the start, two rival guerrilla movements, the Chetniks and the Partisans, engaged in a bloody civil war with each other, in addition to fighting against the occupying forces. Some Chetniks

In August 1941 Kosta Pećanac put himself and his Chetniks at the disposal of Milan Nedić's government, becoming the occupation regime's ‘legal Chetniks'.[202] At the peak of their strength in mid-May 1942, the two legal Chetnik auxiliary forces numbered 13,400 men; these detachments were dissolved by the end of 1942.[193] Pećanac was captured and executed by forces loyal to his Chetnik rival Draža Mihailović in 1944. As no single Chetnik organization existed,[202] other Chetnik units engaged independently in marginal[203] resistance activities and avoided accommodations with the enemy.[198][204] Over a period of time, and in different parts of the country, some Chetnik groups were drawn progressively[203][205] into opportunist agreements: first with the Nedić forces in Serbia, then with the Italians in occupied Dalmatia and Montenegro, with some of the Ustaše forces in northern Bosnia, and after the Italian capitulation, also with the Germans directly.[206] In some regions Chetniks collaborated "extensively and systematically", which they called "using the enemy".[206][207][208]

Ethnic Russian units

The Auxiliary Police Troop and the Russian Protective Corps were paramilitary units raised in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, composed exclusively of anti-communist White émigrés or Volksdeutsche from Russia, under the command of General Mikhail Skorodumov (around 400 and 7,500 men respectively by December 1942).[209] The force reached a peak size of 11,197 by September 1944.[210] Unlike the Serbian units, the Russian Protective Corps was part of the German armed forces and its members took the Hitler Oath.[193]

Banat

Between April 1941 and October 1944, the Serbian half of the

According to German sources, as of 28 December 1943, the Volksdeutsche minority of the Banat had contributed 21,516 men to the Waffen SS, the auxiliary police, and the Banat police.[189]

The 700,000 Volksdeutsche who lived in Yugoslavia[212] were the basis for the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen, which towards the war's end included other ethnicities. The division's soldiers brutally punished civilians accused of working with partisans in both occupied Serbia and the Independent State of Croatia, going so far as to raze entire villages.[213][failed verification]

Montenegro

The Italian governorate of Montenegro was established as an Italian protectorate with the support of Montenegrin separatists known as Greens. The Lovćen Brigade, the militia of the Greens, collaborated with the Italians. Other collaborationist units included local Chetniks, police, gendarmerie and Sandžak Muslim militia.[214]

Kosovo

Most of Kosovo and the western part of southern Serbia (Juzna Srbija, included in

The Balli Kombëtar militias, or Ballistas, were volunteer Albanian nationalistic groups that started as a resistance movement, then collaborated with the Axis Powers in hopes of seeing Greater Albania created.[218] Military units were formed within the militias, among them the Kosovo Regiment, raised in Kosovska Mitrovica as a Nazi auxiliary military unit after Italian capitulation.[219][page needed] According to German reports, in early 1944 some 20,000 Albanian guerrillas led by Xhafer Deva fought the Partisans alongside the Wehrmacht in Albania and Kosovo.[189]

Macedonia

In Bulgaria-annexed Vardar Macedonia, the occupation authority organized the Ohrana into auxiliary security forces. On 11 March 1943, Skopje's entire Jewish population was deported to the gas chambers of Treblinka concentration camp.[220]

Slovene Lands

The Axis powers divided the Slovene Lands into three zones. Germany occupied the largest, northern part. Italy annexed the southern part, and Hungary annexed the northeast part, Prekmurje.[221] As in the rest of Yugoslavia, the Nazis used the Slovene Volksdeutsche to further their aims, in groups like the Deutsche Jugend (German Youth) which was used as an auxiliary military force for guard duty and fighting the partisans, and the Slovenian National Defense Corps.[221]

The

The Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia (MVAC), was under Italian authority. One of the biggest components of the MVAC was the Civic Guards (Vaške Straže [sl]),[222] a Slovene volunteer military organization formed by the Italian Fascist authorities to fight the partisans, as well as some collaborationist Chetniks units. The Legion of Death (Legija Smrti), was another Slovene anti-partisan armed unit formed after the Blue Guard joined the MVAC.[221]

Independent State of Croatia

On 10 April 1941, a few days before Yugoslavia's capitulation, Ante Pavelić's Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established as an Axis-affiliated state, with Zagreb as capital.[224] Between 1941 and 1945, the fascist Ustaše regime collaborated with Nazi Germany, and engaged in independent persecution. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, this resulted in the deaths of approximately 30,000 Jews, between 25,000 and 30,000 Roma, and between 320,000 and 340,000 ethnic Serbs from Croatia and Bosnia,[225] in camps like the infamous Jasenovac concentration camp.[226][227]

The 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Handschar (1st Croatian), created in February 1943, and the 23rd Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Kama (2nd Croatian), created in January 1944, were manned by Croats and Bosniaks as well as local Germans. Earlier in the war, Pavelić formed a Croatian Legion for the Eastern Front and attached it to the Wehrmacht. Volunteer pilots joined the Luftwaffe as Pavelić did not want to get his army directly involved for both propaganda reasons (Domobrans/Home Guards were a "chieftain of Croatian values, never attacking and only defending") and due to a safeguarding need for political flexibility with the Soviet Union.

Pavelić proclaimed that Croats were the descendants of Goths, to eliminate the leadership's inferiority complex and be better viewed by the Germans. The Poglavnik stated that "Croats are not Slavs, but Germanic by blood and race".[228] Nazi German leadership was indifferent to this claim.[citation needed]

Bosnia

In 1941 Bosnia became an integral part of the Independent State of Croatia. Bosnian Muslims were considered Croats of Islamic confession.[229]

Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941 and, by November 1942, Nazi Germany had occupied around 750,000 sq mi (1,900,000 km2) of the Soviet Union.[230] By November 1944, the German forces had been forced out of the pre-World War II Soviet territory.[230]

According to the American historian Jeffrey Burds, out of the three million armed collaborators with Nazi Germany in Europe, as many as 2.5 million originated from the Soviet Union, and by 1945, every eighth German soldier had previously been a pre-war Soviet citizen.

Toward's the war's end, the

According to Antony Beevor, those serving under the Germans were "often extraordinarily naïve and ill-informed."[232] Many viewed their service under the Germans as just serving in another military service and a way to ensure food for themselves, which they preferred to being maltreated and starved in a prisoner-of-war camp.[232]

The Waffen-SS recruited from many nationalities living in the Soviet Union, and the German government attempted to enroll Soviet citizens voluntarily for the Ostarbeiter program. Originally this effort worked well, but the news of the terrible conditions faced by workers dried up the flow of new volunteers and the program became forcible.[235]

Hiwis

Already from the very first days, individual deserters and prisoners from the Red Army were offering their help to the Germans in auxiliary duties such as, but not limited to, cooking, driving, and medical assistance.[233] There were also Soviet civilians that joined supply units and construction battalions.[230] Both military and civilian auxiliaries were called Hiwis (German abbreviation for auxiliary volunteer) with the former Soviets soldiers frequently wearing their Red Army uniforms without any Soviet insignia.[230] After two months service, they were permitted to wear German uniforms with insignia and ranks, which made veteran Hiwis almost indistinguishable from the regular German soldiers, although their promotion up the ranks was very limited.[230]

Hitler reluctantly gave permission in September 1941 to recruit people from the Soviet Union as unarmed voluntary assistants, but in practice this was frequently ignored and many of them served in frontline units. The failure of the Axis powers to immediately defeat the Soviet Union in late 1941 led the Wehrmacht to resort to new sources of manpower necessary for a protracted war.

Between early 1942 and late 1943, the Kommando der Ostlegionen in Polen formed a total of 54 battalions, but this was not the only place where such units were being created:[238]

In Russia proper, ethnic Russians governed the semi-autonomous Lokot Autonomy in Nazi-occupied Russia.[239] On 22 June 1943, a parade of the Wehrmacht and Russian collaborationist forces was welcomed and positively received in Pskov. The entry of Germans into Pskov was labelled "Liberation day" by occupying authorities, and the old Russian tricolor flag was included in the parade.[240]

The Eastern Legions

Ethnic groups from the USSR

Estimates of people that served in the Wehrmacht

~70,000[234]

Azerbaijanis

<40,000[234]

<30,000[234]

Georgians

25,000[234]

Armenians

20,000[234]

Volga Tatars

12,500[234]

Crimean Tatars

10,000[234]

Kalmyks

7,000[234]

Cossacks

70,000[234]

Total

280,000[234]

Legion

No. of battalions formed

Turkestan

15

Armenian

9

Georgian

8

Azerbaijani

8

Idel-Ural (Volga Tartars)

7

North Caucasian

7

Total

54

Russia

Kalmykians

Belarus

In

Many Belarusian collaborators retreated with German forces in the wake of the Red Army advance. In January 1945, the

Transcaucasia

Ethnic Armenian, Georgian, Turkic and Caucasian forces deployed by the Germans consisted primarily of Soviet Red Army POWs assembled into ill-trained legions.[citation needed] Among these battalions were 18,000 Armenians, 13,000 Azerbaijanis, 14,000 Georgians, and 10,000 men from the "North Caucasus."[243] American historian Alexander Dallin notes that the Armenian and Georgian Legions were sent to the Netherlands as a result of Hitler's distrust of them, and many later deserted.[244] Author Christopher Ailsby called the Turkic and Caucasian forces formed by the Germans "poorly armed, trained and motivated", and "unreliable and next to useless".[243]

The

Collaboration beyond Europe with the European Axis powers

Egypt and the Palestine mandate

The well-publicized

In the 1940s the situation worsened. Sporadic pogroms began in 1942.[undue weight? – discuss][citation needed]

French colonial empire

France retained its colonial empire, and the terms of the armistice shifted the balance of power of France's reduced military resources away from metropolitan France and towards its overseas possessions, especially French North Africa. Although in 1940, most French colonies except for the French Equatorial Africa had rallied to Vichy France, this changed during the war. By 1943, all French colonies, except for Japanese-controlled French Indochina, were under the control of the Free French.[249] French Equatorial Africa in particular played a key role.[250]

French North Africa

Concerned that the French fleet might fall into German hands, the British Royal Navy sank or disabled most of it in the July 1940 attack on the Algerian naval port at Mers-el-Kébir, which poisoned Anglo-French relations and led to Vichy reprisals.[251] When Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa, began on 8 November 1942 with landings in Morocco and Algeria, Vichy forces initially resisted, killing 479 and wounding 720. Admiral François Darlan appointed himself High Commissioner of France (head of civil government) for North and West Africa, then ordered Vichy forces there to stop resisting and co-operate with the Allies, which they did.[252][253][page needed]

Most Vichy figures were arrested, including Darlan and General Alphonse Juin,[254] chief commander in North Africa. Both were released, and US General Dwight D. Eisenhower accepted Darlan's self-appointment. This infuriated de Gaulle, who refused to recognise Darlan. Darlan was assassinated on Christmas Eve 1942 by a French monarchist. German Wehrmacht forces in North Africa established the Kommando Deutsch-Arabische Truppen, composed of two battalions of Arab volunteers of Tunisian origin, an Algerian battalion and a Moroccan battalion.[255] The four units had total of 3,000 men; with German cadres.[256]

Morocco

In 1940, Résident Général Charles Noguès implemented antisemitic decrees coming from Vichy excluding Moroccan Jews from working as doctors, lawyers or teachers.[257][258] [259] All Jews living elsewhere were required to move to the Jewish quarters, called mellahs,[257] Vichy anti-semitic propaganda encouraged boycotting Jews,[257] and pamphlets were pinned to Jewish shops.[257] These laws put Moroccan Jews in an uncomfortable position "between an indifferent Muslim majority and an antisemitic settler class."[258] Sultan Mohammed V reportedly refused to sign off on "Vichy's plan to ghettoize and deport Morocco's quarter of a million Jews to the killing factories of Europe," and, in an act of defiance, insisted on inviting all the rabbis of Morocco to the 1941 throne celebrations.[260]

Tunisia

Many Tunisians took satisfaction in France's defeat by Germany in June 1940,

French Equatorial Africa

The federation of colonies in

Syria and the Lebanon (League of Nations mandates)

The Vichy government's Armée du Levant (

The

After the Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre, on 14 July 1941, 37,736 Vichy French prisoners of war survived, who mostly chose to be repatriated rather than join the Free French.

Foreign volunteers

French military volunteers

French volunteers formed the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (LVF), Légion impériale, SS-Sturmbrigade Frankreich and finally in 1945 the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French), which was among the final defenders of Berlin.[268][269][270]

Volunteers from British India

The Indian Legion (Legion Freies Indien, Indische Freiwilligen Infanterie Regiment 950 or Indische Freiwilligen-Legion der Waffen-SS) was created in August 1942, recruiting chiefly from disaffected British Indian Army prisoners of war captured by Axis forces in the North African campaign. Most were supporters of the exiled nationalist and former president of the Indian National Congress Subhas Chandra Bose. The Royal Italian Army formed a similar unit of Indian prisoners of war, the Battaglione Azad Hindoustan. (A Japanese-supported puppet state, Azad Hind, was also established in far-eastern India with the Indian National Army as its military force.)[271][272]

Non-German units of the Waffen-SS

By the end of World War II, 60% of the Waffen-SS was made up of non-German volunteers from occupied countries.[

The

Business collaboration

A number of international companies have been accused of having collaborated with Nazi Germany before their home countries' entry into World War II, though it has been debated whether the term "collaboration" is applicable to business dealings outside the context of overt war.[276][who?]

American companies that had dealings with Nazi Germany included Ford Motor Company,[277] Coca-Cola,[278][279] and IBM.[280][unreliable source?][281][282]

Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. acted for German tycoon Fritz Thyssen, who helped finance Hitler's rise to power.[283] The Associated Press (AP) supplied images for a propaganda book called The Jews in the USA, and another titled The Subhuman.[284]

In December 1941, when the United States entered the war against Germany, 250 American firms owned more than $450 million of German assets.[285] Major American companies with investments in Germany included General Motors, Standard Oil, IT&T, Singer, International Harvester, Eastman Kodak, Gillette, Coca-Cola, Kraft, Westinghouse, and United Fruit.[285] Many major Hollywood studios have also been accused of collaboration, in making or adjusting films to Nazi tastes prior to the U.S. entry into the war.[276]

German financial operations worldwide were facilitated by banks such as the Bank for International Settlements, Chase and Morgan, and Union Banking Corporation.[285]

"as the US entered the war, it found that some technologies or resources could not be procured, because they were forfeited by American companies as part of business deals with their German counterparts."[286]

After the war, some of those companies reabsorbed their temporarily detached German subsidiaries, and even received compensation for war damages from the Allied governments.[285]

See also

- Blue Division

- Collaboration in wartime

- Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China

- Finland in World War II

- German-occupied Europe

- Italian Civil War

- International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania

- List of Allied traitors during World War II

- Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

- Pursuit of Nazi collaborators

- Resistance during World War II

- Responsibility for the Holocaust

Notes

- ^ "A few thousand of the deportees were simply abandoned by their captors in the areas surrounding Kaminets-Podolsk. Most subsequently perished with Jewish residents of the area as a result of transports or aktions in the many ghettos, but a handful survived.[156] The killings were conducted on August 27 and August 28, 1941, in the Soviet city of Kamianets-Podilskyi (now Ukraine), occupied by German troops in the previous month on July 11, 1941.[157] The number of people deported over the Carpathians was 19,426, according to a document found in 2012[158]

References

- ^ Darcy 2019, p. 75.

- S2CID 144309794.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-1263-9.

- S2CID 144135929.

- ^ German Invasion of Western Europe, May 1940, Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ^ B. De Wever, Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (VNV) at Belgium-WWII, ("Au sein de la direction du parti, on retrouve deux tendances: une aile fasciste et une aile modérée.")

- ISBN 978-0-7524-6393-3"by June the plum jobs in the Belgian administration had been grabbed by VNV men"

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-929131-1.

- ISBN 978-90-334-8039-3.

- ISBN 978-2-87495-001-8.

- ^ a b Dumoulin & Witte 2006, pp. 20–26.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-87495-001-8.

- ISBN 2-87386-485-0.

- ISBN 2-87027-940-X.

- ^ Ministerie van Justitie. Commissariaat-generaal van de gerechtelijke politie / Ministère de la Justice. Commissariat-général de la police judiciaire, European Holocaust Research Infrastructure

- ISBN 978-2-87495-001-8.

- ISBN 90-5867-498-3.

- ^ ISBN 1-85973-274-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-969434-1.

- ^ Laporte, Christian (10 August 1994). "Un Oradour flamand à Meensel-Kiezegen". Le Soir. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Bunting, Madeleine (1995), The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940–1945, London: Harper Collins Publisher, pp. 51, 316

- ^ Hansard (Commons), vol. 430, col. 138

- ISBN 0-19-285087-3

- ^ War Profits Levy (Jersey) Law 1945

- ^ War Profits (Guernsey) Law 1945

- ^ Occupation Diary, Leslie Sinel, Jersey 1945

- ^ Jørgen Hæstrup, Secret Alliance: A Study of the Danish Resistance Movement 1940–45. Odense, 1976. p. 9.

- ^ Phil Giltner, "The Success of Collaboration: Denmark's Self-Assessment of its Economic Position after Five Years of Nazi Occupation," Journal of Contemporary History 36:3 (2001) p. 486.

- ^ Henning Poulsen, "Hvad mente Danskerne?" Historie 2 (2000) p. 320.

- ISBN 978-0429769603.

- ^ a b RESCUE, EXPULSION, AND COLLABORATION: DENMARK'S DIFFICULTIES WITH ITS WORLD WAR II PAST, Vilhjálmur Örn Vilhjálmsson and Bent Blüdnikow, Jewish Political Studies Review Vol. 18, No. 3/4 (Fall 2006), pp. 3–29 (27 pages) Published By: Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, retrieved February 14, 2023

- ^ Voorhis 1972, p. 174.

- ^ "Statsminister Vilhelm Buhls Antisabotagetale 2 September 1942" (in Danish). Aarhus University. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "Samarbejdspolitikken under besættelsen 1940–45" (in Danish). Aarhus University. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Frisch, Hartvig (1945). Danmark besat og befriet – Bind II. Forlaget Fremad. p. 390.

- ^ "Danmark og de jødiske flygtninge 1938–1945: Flygtningestop" (in Danish). Dansk Institut for Internationale Studier. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ Weiss, Jakob (5 May 2005). "Anders Fogh siger undskyld" [Anders Fogh apologizes]. Berlingske (in Danish). Archived from the original on 2 August 2021.

- ^ Voorhis 1972, p. 175.

- ^ Poulsen, Historie, 320.

- ISBN 978-87-557-2201-9.

- ^ Why did France lose to Germany in 1940?, Stéphanie Trouillard, France24, May 16, 2020

- ISBN 0-14-024159-0

- ISBN 978-1-107-04746-4.

- ^ Davey 1971, p. 29.

- ISBN 978-0-19-162288-5.

- ISBN 978-1-350-00654-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-230-50392-2.

- ^ ["Berlière, Jean-Marc"] (27 April 2007). "L'impossible pérennité de la police républicaine sous l'Occupation". Centre de ressources et d’ingénierie documentaires de l'INSP (in French).

- ^ Littlejohn, D. (1981). Foreign Legions of the Third Reich: Norway, Denmark, France. R.J. Bender. pp. 170–172.

- ISBN 978-2-7540-5365-5.

- ISBN 978-2-7154-0508-0.

- ISBN 978-0-231-51609-9.

- ISBN 978-2-262-07989-5.

- ^ ISBN 979-10-210-2264-5.

- S2CID 161622751.

- ISBN 978-0-520-30489-5.

- ^ Pesnot, Patrick; Denantes, Rebecca; Kern, Christine; Billoud, Michèle; Fauquet, Marie-Hélène (4 April 2021). "Juin 1940 : les négociations entre le PCF et les Allemands". France Inter (in French).

- ISBN 978-1-134-97423-8.

- ISBN 978-1-84737-759-3.

- ISBN 978-0-935216-64-6.

- ISBN 978-0-00-752081-7.

- ^ "STO" (in French). Larousse.

- ^ Chronology of Repression and Persecution in Occupied France, 1940–44, Fontaine Thomas Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network, Sciences Po, 19 November 2007. ("Laval was running the risk of having the French State sanction and participate in the success of an exclusively Nazi program, simply in order to maintain the illusion of French sovereignty")

- ^ France Confronts the Holocaust, Jean-Marc Dreyfus, Brookings Institution, December 1, 2001.

- ^ Was Vichy France a Puppet Government or a Willing Nazi Collaborator? Lorraine Boissoneault, Smithsonian Magazine, November 9, 2017, accessed February 18, 2023.

- ISBN 0-8052-0972-7, Table 918, p. 1208.

- ^ For example, Alfred Cobban, A History of Modern France: Volume 3: 1871–1962, Penguin Books, 1965, page 200: "The official figure of some three or four thousand is a gross understatement which must be multiplied by at least ten."

- ^ "Heim ins Reich: La 2e guerre mondiale au Luxembourg – quelques points de repère". Centre national de l'audiovisuel. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007.

- ]

- ^ "Dutch Jew-hunters who massively helped the Nazis". Arutz Sheva. 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Archive to reveal new details on WWII Jews' arrests". NBC News. 12 April 2011.

- ^ Siegal, Nina (25 April 2023). "Dutch to Make Public the Files on Accused Nazi Collaborators". The New York Times.

- ^ Norway profile – Leaders, BBC, 17 April 2012

- ^ "He didn't mean to harm any good Norwegian" – the acquittal of Knut Rød, one of the organisers of the Norwegian Jew's deportation to Auschwitz, Seventh European Social Science History conference 26 February – 1 March 2008 Archived 19 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 10 March 2008

- ^ Myklebost, Tor (1943). Front cover image for They came as friends They came as friends. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co. p. 43.

- ^ "Justice – I". Time Magazine. 5 November 1945. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ The Norwegian TV series that's enraged the Kremlin: And why you should watch it, James Kirchick, Politico, March 20, 2016

- ISBN 978-86-7179-052-9. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

In this new satellite Fascist-type state, the Italian Government set up an Albanian voluntary militia numbering 5,000 men — the Vulnetari — to help the Italian forces maintain order as well as to independently conduct surprise attacks on the Serb population.

- ISBN 978-1-85065-278-6. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

the activities of numerous Albanian nationalist movements, and life consequently became increasingly difficult for Kosovo's Serb population, whose homesteads were routinely sacked by the Vulnetari.

- ^ Božović 1991, p. 85

Вулнетари су на Косову и Метохији, али и у суседним крајевима, спалили стотине српских и црногорских села, убили мноштво људи и извршили безброј пљачки.

- ISBN 978-0-14-311610-3)

- ^ Birn 2001, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Wnuk 2018, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Wnuk 2018, p. 58.

- ^ a b Wnuk 2018, p. 65.

- ^ a b Wnuk 2018, p. 66.

- ^ Birn 2001, p. 183.

- ^ a b Wnuk 2018, p. 95.

- ^ a b Birn 2001, p. 184.

- ^ Birn 2001, pp. 184–85.

- ^ Birn 2001, pp. 191–97.

- ^ Birn 2001, p. 187–88.

- ^ Birn 2001, pp. 190–91.

- ^ a b c d e Hiio 2011, p. 268.

- ^ Hiio 2011, p. 268-269.

- ^ Hiio 2011, pp. 269–70.

- ^ a b Hiio 2011, p. 270.

- ^ Hiio 2011, p. 269.

- ^ Hiio 2011, pp. 271–72.

- ^ Hiio 2011, p. 271.

- ^ Birn 2001, pp. 181–198.

- ^ "Conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Phase II – The German Occupation of Estonia, 1941–1944" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Angrick & Klein 2009, pp. 65–70.

- ^ a b Breitman 1991.

- ^ a b c Birn 1997.

- ^ a b c d Haberer 2001.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 194.

- ISBN 978-5-9990-0020-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-9984-9054-3-3, pp. 182–89

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987

- ^ a b Valdis O. Lumans. Book Review: Symposium of the Commission of the Historians of Latvia, The Hidden and Forbidden History of Latvia under Soviet and Nazi Occupations, 1940–1991: Selected Research of the Commission of the Historians of Latvia, Vol. 14, Institute of the History of Latvia Publications:European History Quarterly 2009 39: 184

- OCLC 66394978.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-820873-0.

- ^ "Arūnas Bubnys. Lietuvių saugumo policija ir holokaustas (1941–1944) | Lithuanian Security Police and the Holocaust (1941–1944)". genocid.lt. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Oshry, Ephraim, Annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry, Judaica Press, Inc., New York, 1995

- ^ Niwiński, Piotr (2011). Ponary: miejsce ludzkiej rzeźni (PDF). Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu; Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, Departament Współpracy z Polonią. pp. 25–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2012.

- ^ Sužiedėlis 2004, p. 339.

- ^ Sužiedėlis 2004, pp. 346, 348.

- ^ Sužiedėlis, Saulius (2001). "The Burden of 1941". Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences. 47 (4). Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Krapauskas, Virgil (2010). "Book Reviews". Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences. 56 (3). Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ Saulius Sužiedėlis: „Holokaustas – centrinis moderniosios Lietuvos istorijos įvykis“ (Saulius Suziedėlis: "The Holocaust is the central event of modern Lithuanian history"), Zigma Vitkus, bernardinai, December 28, 2010

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7864-0371-4. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ Peter Gessner (29 July 1942). "Life and Death in the German-established Warsaw Ghetto". Info-poland.buffalo.edu. Archived from the original on 18 August 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Хлокост на юге Украины (1941–1944): (Запорожская область) [The Holocaust in the south of Ukraine (1941–1944): (Zaporizhia region)]. holocaust.kiev.ua (in Russian). 2003. Archived from the original on 27 August 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-4969-5. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ a b Michael MacQueen, The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, pp. 27–48, 1998, [1] Archived 21 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Browning & Matthäus 2007, pp. 244–294.

- ^ Konrad Kwiet, Rehearsing for Murder: The Beginning of the Final Solution in Lithuania in June 1941, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, pp. 3–26, 1998, [2] Archived 12 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Salonikaand western Macedonia, which were under German and Italian control, and established propaganda centres to secure the allegiance of the approximately 80,000 Slavs in these regions. The Bulgarian plan was to organize these Slavs militarily in the hope that Bulgaria would eventually assume the administration there. The appearance of the Greek left wing resistance in western Macedonia persuaded the Italian and German and authorities to allow the formation of Slav security battalions (Ohrana) led by Bulgarian officers.

- ISBN 0-8108-5565-8, pp. 162–163.

- S2CID 159537859.

- JSTOR 20028917.

- ^ Kárný 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Cornwall 2011, p. 221.

- Hitler: Volume I: Ascent 1889–1939. pp. 752–53.

- ^ "Vladimír Měřínský (1934–2022)". www.memoryofnations.eu. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Ecce Homo – Jaroslav Eminger, Český rozhlas, July 14, 2004 (in Czech)

- ^ "The Tragic Destiny of Romeo Reisinger: Death a Few Hours before Liberation". vhu.cz (in Czech). Army Museum. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler's Greece. The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44(Greek translation), Athens: Αλεξάνδρεια, 1994(1993),125.

- ^ Juan Carmona Zabala sheds light on tobacco trade in modern Greece and Germany, Joanie Blackwell, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, June 29, 2017

- ^ Chimbos, Peter D. (1999), "Greek Resistance 1941–45 : Organization, Achievements and Contributions to Allied War Efforts Against the Axis Powers", International Journal of Comparative Sociology, Brill

- ^ Hondros 1983, p. 81.

- ^ Mazower 1995, p. 324.

- ^ Markos Vallianatos, The untold history of Greek collaboration with Nazi Germany (1941–1944)

- ^ Russell King, Nicola Mai, and Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers. The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press, 2005

- ISBN 978-3-86153-447-1. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ ], accessed 18 Feb. 2023

- ^ Kursietis, Andris J., and Antonio J. Munoz. The Hungarian Army and Its Military Leadership in World War II. Bayside, NY: Axis Europa & Magazines, 1999. Print.

- ISBN 0-8143-2691-9.

- ^ "degob.org". degob.org. 28 August 1941. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- ^ Martin Davis. "Kamyanets-Podilskyy" (PDF). pp. 11–14 / 24 in PDF – via direct download. Also in: Martin Davis (2010). "The Nazi Invasion of Kamenets". JewishGen.

- ^ Betekintő. "A few thousand of the deportees ..." Betekinto.hu. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 408.

- ^ Weinberg 2005, pp. 48–121.

- ISBN 978-1-4616-4308-1.

During the war, while in most European countries the Germans found collaborators that set up puppet governments, Poland had no such collaborationist governments. The Germans arrested masses of Polish intellectuals, whom they perceived as a threat. As a result, thousands of Poles lost their lives during that occupation.

- ISBN 978-0-7391-7459-3.

the Polish government had never surrendered

- ISBN 978-0-230-51137-8.

- ISBN 978-1-78096-241-2.

- ISBN 978-1-78200-447-9.

After suffering a devastating defeat in 1939 at the hands of the Germans, many Polish troops escaped to Hungary and Romania and subsequently to France

- ISBN 978-1-107-67148-5.

At the start of October 1939, the German occupiers divided in two the area of Poland they had occupied... annexing to Germany the western territories and designating central Poland a colonial territory which they labeled the 'General Government...

- ^ Hempel, Adam (1987). Policja granatowa w okupacyjnym systemie administracyjnym Generalnego Gubernatorstwa: 1939–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw: Instytut Wydawniczy Związków Zawodowych. p. 83.

- ^ Grabowski 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Higher SS- and Police Leader (HSSPF) for the Generalgouvernement Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger (October 30, 1939). Aufruf/Odezwa (Appeal).

- ISBN 978-0-253-01074-2.

- ^ Grabowski 2016, pp. 7–11.

- ^ Grabowski 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Grabowski 2016, p. 8.

- ISBN 978-0-415-27509-5.

- ISBN 978-83-01-09291-7.

- ^ Marci Shore. "Gunnar S. Paulsson Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw 1940–1945". The American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8

- ^ Browning & Matthäus 2007, p. 32.

- ISBN 978-1-78625-716-1. Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- JSTOR 3649910.

- JSTOR 3649912.

- ^ a b c International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania (11 November 2004). "Executive Summary: Historical Findings and Recommendations" (PDF). Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Yad Vashem (The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority). Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Revisited: Romania's Iași pogrom, one of the worst massacres of Jews during World War II, Nadia Bletry, Thierry Trelluyer, Ruth Michaelson. France24, March 23, 2022

- ISSN 1528-4808Editors Alex J. Kay, Jeff Rutherford, David Stahel Publisher University Rochester Press, 2012ISBN 978-1-58046-407-9

- ^ The JUST Act Report: Moldova, US Department of State

- ISBN 978-0-09-471260-7.

- ISBN 978-0-598-52382-2.

- ISBN 978-0-300-17883-8.

- ^ a b c Tomasevich 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Tomasevich 2002, p. 612.

- ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- ^ McDonald, G.C.; United States. Department of the Army (1973). Area Handbook for Yugoslavia. Area handbook series. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Tomasevich 2002, p. 189.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89096-760-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8101-2862-0.

- ISBN 978-0-9753432-0-3.

- ISBN 978-2-916713-00-7.

- ^ a b Ramet 2006, p. 147

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 223–25

- ^ MacDonald 2002, pp. 140–142

- ^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 65–67

- ^ a b Glenny 2000, p. 489.

- ^ a b Milazzo 1975, p. 182

- ^ Milazzo 1975, p. 21

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. [page needed]

- ^ a b Tomasevich 1975, p. 169

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 246

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 145 "Both the Chetniks' political program and the extent of their collaboration have been amply, even voluminously, documented; it is more than a bit disappointing, thus, that people can still be found who believe that the Chetniks were doing anything besides attempting to realize a vision of an ethnically homogeneous Greater Serbian state, which they intended to advance, in the short run, by a policy of collaboration with the Axis forces. The Chetniks collaborated extensively and systematically with the Italian occupation forces until the Italian capitulation in September 1943, and beginning in 1944, portions of the Chetnik movement of Draža Mihailović collaborated openly with the Germans and Ustaša forces in Serbia and Croatia."

- ^ Tomasevich 2002, p. 192.

- ISBN 978-0-89096-760-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-316-77306-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4985-2941-9.

- ^ Glišić, Venceslav (1970). ""TEROR" I "ZLOČINI" NACISTIČKE NEMAČKE U SRBIJI 1941–1945". znaci.net. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019.

- ^ War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941–1945 Archived 15 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Jozo Tomasevich. Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0-912138-29-9.

- ISBN 978-1-908273-99-4.

- ^ World Jewish Congress (2008). The Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. Israel Council on Foreign Relations.

- ISBN 978-1-904687-37-5.

- ISBN 978-0-88033-375-7.

- ISBN 978-1-56171-081-2.

- ^ a b c Tomasevich 2002, p. 83.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85065-428-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-1330-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8229-7793-3.

- ^ "Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia". Holocaust Encyclopedia. 11 March 1943.

- ^ "Jasenovac". The Holocaust Encyclopedia. 10 April 1941.

- ^ "List of Individual Victims of Jasenovac Concentration Camp". Official website of the Jasenovac Memorial Site. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Беляков 2009, p. 146.

- ISBN 978-0-932885-12-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4728-0687-1.

- S2CID 159523593.

- ^ a b c d Beevor, Antony. The Fall of Berlin 1945. pp. 113–114.

- ^ ISBN 0-85045-524-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Drobyazko, S.; Karashchuk, A. (2001). Восточные легионы и казачьи части в Вермахте [Eastern legions and Cossack units in the Wehrmacht] (in Russian). Moscow. pp. 3–4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Andrew Gregorovich. "InfoUkes: Ukrainian History – World War II in Ukraine". infoukes.com. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820873-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8179-9183-8.

- ^ ISBN 0-85045-524-3.

- ISBN 978-90-04-46184-0.

- S2CID 158890368.

- ISBN 978-0-313-30921-2.

- Journal of Genocide Research Volume 2, 2000 – Issue 2

- ^ a b Ailsby 2004, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Dallin, Alexander. German Rule in Russia: 1941–1945. Octagon Books: 1990.

- ^ Auron 2003, p. 238.

- ^ Christopher J. Walker's "Armenia —The Survival of a Nation," page 357

- ^ Joel Beinin, Introduction

- ^ JSTOR 25834622– via Jstor.

- ^ Thomas 2007.

- ^ Jennings 2015.

- ^ See, for example, Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, Volume 2: Their Finest Hour, London & New York, 1949, Book One, chapter 11, "Admiral Darlan and the French Fleet: Oran"

- S2CID 159589846.

- ^ Funk 1974.

- ^ Alphonse Juin (1888–1967), Chemins de mémoire, Ministère des Armées (Ministry of Armies), Republic of France

- ISBN 978-1-78438-231-5.

- ISBN 978-84-414-3173-7.

- ^ ISSN 1362-9387

- ^ a b Miller 2013, p. 45.

- ^ "Le Petit Marocain". Gallica. 24 June 1945. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Moroccan Jews pay homage to 'protector' – Haaretz Daily Newspaper | Israel News. Haaretz.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-04.

- ^ Perkins 2004, p. 105.

- ^ a b Perkins 1986, p. 180.

- ^ a b Mollo 1981, p. 144.

- ^ Playfair 2004, pp. 200, 206.

- ^ Long 1953, pp. 333–334, 36.

- ^ a b Sutherland & Canwell (2011), p. 43.

- ^ Shores & Ehrengardt (1987), p. 30.

- ^ Felton 2014, pp. 145, 152, 154.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 407.

- ^ Hamilton 2020, pp. 349, 386.

- ISBN 978-1-4766-3337-4.

Imperial Japan in 1943 had established a puppet state known as the Provisional Government of Free India

- ISBN 0-472-08342-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8117-3581-0.

- ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.

- Nuremberg Trial Proceedings, Volume 22, September 1946 Archived 21 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Mark Thomas discovers Coca-Cola's Nazi links". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Coca-Cola collaborated with the Nazis in the 1930s, and Fanta is the proof". Timeline. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Black, Edwin (27 February 2012). "IBM's Role in the Holocaust – What the New Documents Reveal". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Black, Edwin. "How IBM Technology Jump Started the Holocaust". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Black, Edwin (19 May 2002). "The business of making the trains to Auschwitz run on time". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (25 September 2004). "How Bush's grandfather helped Hitler's rise to power". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "What the AP's Collaboration With the Nazis Should Teach Us About Reporting the News". Tablet Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Stone & Kuznick 2013, p. 82.

- ISBN 978-0-313-38503-2.

Bibliography

- Ailsby, Christopher (2004). Hitler's renegades: foreign nationals in the service of the Third Reich (1st ed.). Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's, Inch. ISBN 9781574888386.

- Angrick, Andrej; Klein, Peter (2009). The "Final Solution" in Riga: Exploitation and Annihilation, 1941–1944. Studies on War and Genocide. Vol. 14. ISBN 978-1-84545-608-5.

- Auron, Yair (2003). The Banality of Denial. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1784-4. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Beinin, Joel. The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry: Culture, Politics, and the Formation of a Modern Diaspora. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry

- Беляков, С.С. (2009). Усташи между фашизмом и этническим на опалимом [Ustaše: between fascism and ethnic nationalism]. Екатеринбург: Гуманитарный ун-т.

- Božović, Branislav (1991). Surova vremena na Kosovu i Metohiji: kvislinzi i kolaboracija u drugom svetskom ratu. Institut za savremenu istoriju. ISBN 978-86-7403-040-0.

- Birn, Ruth Bettina (March 1997). "Revising the Holocaust". The Historical Journal. 40 (1): 195–215. S2CID 162951971.

- S2CID 143520561.

- Breitman, Richard (September 1991). "Himmler and the 'Terrible Secret' among the Executioners". Journal of Contemporary History. 26 (3/4). Sage Publications: 431–451. S2CID 159733077.

- Browning, Christopher R.; Matthäus, Jürgen (2007). The origins of the final solution: the evolution of Nazi Jewish policy, September 1939 - March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press [u.a.] ISBN 978-0803259799.

- Cornwall, Mark (2011). "The Czechoslovak Spinx: 'Moderate and Reasonable' Konrad Henlein". In Rebecca Haynes; Martyn Rady (eds.). In the Shadow of Hitler: Personalities of the Right in Central and Eastern Europe. London: I.B.Tauris. pp. 206–227. ISBN 978-1780768083.

- Darcy, Shane (2019). "Coming to Terms with Wartime Collaboration: Post-Conflict Processes & Legal Challenges". Brooklyn Journal of International Law. 45 (1): 75–135.

- Davey, Owen Anthony (1971). "The Origins of the Légion des volontaires français contre le Bolchévisme". Journal of Contemporary History. 6 (4): 29–45. S2CID 153579631.

- Dumoulin, Michel; Witte, Els (2006). Nouvelle histoire de Belgique (in French). Brussels: Editions Complexe. ISBN 2-8048-0078-4.

- ISBN 978-1-78159-305-9.

- Funk, Arthur Layton (1974). The Politics of Torch: The Allied Landings and the Algiers Putsch, 1942. ISBN 978-0-7006-0123-3.

- Glenny, M. (2000). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. A Penguin book. History. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-85338-0.

- Grabowski, Jan (17 November 2016), The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust (PDF), Ina Levine Annual Lecture, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, retrieved 1 March 2023

- Haberer, Eric (December 2001). "Intention and feasibility: Reflections on collaboration and the final solution". East European Jewish Affairs. 31 (2): 64–81. S2CID 143574047.

- Hiio, Toomas (2011). "Estonian Units in the Wehrmacht, SS and Police System, as well as the Waffen-SS, during World War II". Eesti Sõjaajaloo Aastaraamat / Estonian Yearbook of Military History. 1.

- Hamilton, A. Stephan (2020) [2008]. Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault on Berlin, April 1945. Helion & Co. ISBN 978-1-912866-13-7.

- Hondros, John Louis (1983). Occupation & Resistance. The Greek Agony 1941–44. New York: Pella Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-918618-24-5.

- Hamilton, A. Stephan (2020) [2008]. Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault on Berlin, April 1945. Helion & Co. ISBN 978-1-912866-13-7

- Jennings, Eric (2015). Free French Africa in World War II: The African Resistance. ISBN 978-1-107-69697-6.

- Kárný, Miroslav (1999). "Fragen zum 8. März 1944" [Questions about 8 March 1944]. Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente (in German) (6). Translated by Liebl, Petr: 9–42.

- Kárný, Miroslav (1994). "Terezínský rodinný tábor v konečném řešení" [Theresienstadt family camp in the Final Solution]. In Brod, Toman; Kárný, Miroslav; Kárná, Margita (eds.). Terezínský rodinný tábor v Osvětimi-Birkenau: sborník z mezinárodní konference, Praha 7.-8. brězna 1994 [Theresienstadt family camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau: proceedings of the international conference, Prague 7–8 March 1994] (in Czech). Prague: Melantrich. ISBN 978-8070231937

- Long, Gavin (1953). "Chapters 16 to 26". Greece, Crete and Syria. Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1, Army. Vol. II (1st online ed.). Canberra: OCLC 3134080.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-6467-8.

- Miller, Susan Gilson (February 2013). "Facing the Challenges of Reform (1860–1894)". A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-04583-4.

- Milazzo, Matteo J. (1975). The Chetnik Movement & the Yugoslav Resistance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1589-8.

- Mazower, Mark (1995). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. United States: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08923-6.

- Mollo, Andrew (1981). The Armed Forces of World War II. London: Crown. ISBN 978-0-517-54478-5.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2007). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.

- Perkins, Kenneth J. (2004). A History of Modern Tunisia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81124-4.

- Perkins, Kenneth J. (1986). Tunisia. Crossroads of the Islamic and European World. Westview Press. ISBN 0-7099-4050-5.

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; et al. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1956]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Germans Come to the Help of their Ally (1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-066-5.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Sužiedėlis, Saulius (2004). Gaunt, David; Levine, Paul A.; Palosuo, Laura (eds.). Collaboration and Resistance During the Holocaust: Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania. Frankfurt am Main, Bern, New York: Peter Lang, and Oxford.

- Stone, Oliver; Kuznick, Peter (2013). The Untold History of the United States. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-1352-0.

- Thomas, Martin (2007). The French Empire at War, 1940–1945. Manchester University Press.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.