Diplomatic history of World War II

| Timelines of World War II |

|---|

| Chronological |

| By topic |

|

| By theatre |

The diplomatic history of World War II includes the major

High-level diplomacy began as soon as the war started in 1939. British Prime Minister

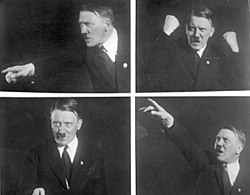

For the Axis powers diplomacy was a minor factor. The alliance of Germany, Italy, and Japan was always informal, with minimal assistance or coordination. Hitler had full control of German diplomatic policies and imposed his will on his allies in Eastern Europe, and with the puppet regime in northern Italy after 1943. Japan's diplomats had a minor role in the war, as the military was in full control. A dramatic failure was the inability of Tokyo to obtain the formulas for synthetic oil from Germany until it was too late to overcome the fatal shortage of fuel for the Japanese war machine. Practically all the neutral countries broke with Germany before the end of the war and thereby were enabled to join the new United Nations.

The military history of the war is covered at World War II. The prewar diplomacy is covered in Causes of World War II and International relations (1919–1939). After the war, diplomacy revolved around the Cold War.

Allies

The

The First Inter-Allied Conference took place in London in early June 1941 between the United Kingdom, the four co-belligerent British Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa), the eight governments in exile (Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia) and Free France.

The

| World War II |

|---|

| Navigation |

|

|

The Grand Alliance

The United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union formed the "Big Three" Allied powers.[2] They were in frequent contact through ambassadors, top generals, foreign ministers and special emissaries such as the American Harry Hopkins. Relations between the three resulted in the major decisions that shaped the war effort and planned for the postwar world.[3] Cooperation between the United Kingdom and the United States was especially close and included forming a Combined Chiefs of Staff. There were numerous high-level conferences; Churchill attended 14 meetings, Roosevelt 12, and Stalin 5. Most visible were the three summit conferences that brought together the three top leaders.[4][5] The Allied policy toward Germany and Japan evolved and developed at these three conferences.[6]

Europe first

At the December 1941

The

Tehran Conference

Following preparation at the Moscow Conference in October–November 1943, the first meeting of the Big Three, Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill, came at the Tehran Conference in Iran from 28 November to 1 December 1943. It agreed on an invasion of France in 1944 (the "Second Front") and dealt with Turkey, Iran, the provisional Yugoslavia, and the war against Japan as well as the postwar settlement.[14]

Yalta Conference

The

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held from 17 July to 2 August 1945, at Potsdam, Germany, near Berlin. Stalin met with the new US President Harry S. Truman and two British prime ministers in succession—Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee. It demanded "unconditional surrender" from Japan, and finalized arrangements for Germany to be occupied and controlled by the Allied Control Commission. The status of other occupied countries was discussed in line with the basic agreements made earlier at Yalta.[16]

The United Nations

The Declaration by United Nations formalized the Allies in January 1942. The Big Four (the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China) were joined by numerous other Allied countries who had signed the Declaration and declared war on the Axis powers. Under Roosevelt's leadership, this "United Nations" alliance in 1945 became a new organization to replace the defunct League of Nations.[17]

Four Policemen

The Four Policemen was a council with the Big Four that U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed as a guarantor of world peace. Their members were called the Four Powers during World War II and were the four major Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the Republic of China. Roosevelt repeatedly used the term "Four Policemen" starting in 1942.[18] As a compromise with internationalist critics, the Big Four nations became the

Moscow Conference of 1943

The October 1943 Moscow Conference resulted in the Moscow Declarations, including the Four Power Declaration on General Security. This declaration was signed by the Allied Big Four—the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and China—and aimed for the creation "at the earliest possible date of a general international organization". This was the first public announcement that a new international organization was being contemplated to replace the League of Nations.

Dumbarton Oaks Conference

At the Dumbarton Oaks Conference or, more formally, the Washington Conversations on International Peace and Security Organization, delegations from the United States and the United Kingdom met first with the delegation from the Soviet Union and then with the delegation from the Republic of China. They deliberated over proposals for the establishment of an organization to maintain peace and security in the world to replace the ineffective League of Nations. The conference was held at Dumbarton Oaks from 21 August 1944 to 7 October 1944. Delegates from other nations participated in the consideration and formulation of these principles.[21]

San Francisco Conference

The San Francisco Conference was a convention of delegates from 50

Anglo-American Relations

Though most Americans favored Britain in the war, there was widespread opposition to American military intervention in European affairs. President Roosevelt's policy of cash-and-carry still allowed Britain and France to purchase munitions from the United States and carry them home.

Churchill, who had long warned against Germany, and demanded rearmament, became prime minister after Chamberlain's policy of appeasement had collapsed and Britain was unable to reverse the

Beginning in March 1941, the United States enacted Lend-Lease sending tanks, warplanes, munitions, ammunition, food, and medical supplies. Britain received $31.4 billion out of a total of $50.1 billion of supplies sent to the Allies. In sharp contrast to the First World War, these were not loans, and no repayment was involved.[25]

Millions of American servicemen were based in Britain during the war, which led to a certain amount of friction with British men and intermarriage with British women. This animosity was explored in art and film, most particularly A Matter of Life and Death and A Canterbury Tale.[26] In 1945 Churchill sent the British Pacific Fleet to help the United States attack and invade Japan.

Casablanca Conference

From January 14–24, 1943 Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Combined Staff met in Casablanca, Morocco. They decided on the major Allied strategy for 1943 in Europe. The main decisions made were to invade Sicily and Italy before Europe, launch strategic bombing against Germany, and approve a U.S. Navy plan to advance on Japan through the Pacific Islands. The invasion of Sicily was an important decision that Churchill pushed for, hoping to defer the Americans' determination to open a second front in France in 1943 to avoid severe Allied casualties. They agreed on a policy of "unconditional surrender". This policy uplifted Allied morale, but it also stiffened the Nazis' resolve to fight to the bitter end.[27]

British Empire

Having signed the

After the French defeat in June 1940, Britain and its empire stood alone in combat against Germany, until June 1941. The United States gave strong diplomatic, financial, and material support, starting in 1940, especially through Lend-Lease, which began in 1941. In August 1941, Churchill and Roosevelt met and agreed on the Atlantic Charter, which proclaimed "the rights of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live" should be respected. This wording was ambiguous and would be interpreted differently by the British, Americans, and nationalist movements.

Starting in December 1941, Japan overran British possessions in Asia, including Hong Kong, Malaya, and especially the key base at Singapore, and marched into Burma, headed toward India. Churchill's reaction to the entry of the United States into the war was that Britain was now assured of victory and the future of the empire was safe, but the rapid defeats irreversibly harmed Britain's standing and prestige as an imperial power. The realisation that Britain could not defend them pushed Australia and New Zealand into permanent close ties with the United States.[28]

Plans for intervention in the Winter War against USSR

The USSR launched the Winter War against Finland in November 1939. The Finns made a remarkable defense against the much larger Soviet forces. The unprovoked invasion excited widespread outrage at popular and elite levels in support of Finland not only in wartime Britain and France but also in the neutral United States.[29] The League of Nations declared the USSR was the aggressor and expelled it. "American opinion makers treated the attack on Finland as dastardly aggression worthy of daily headlines, which thereafter exacerbated attitudes toward Russia."[30] Elite opinion in Britain and France swung in favor of military intervention. Winston Churchill, as head of the Royal Navy, and French Premier Paul Reynaud were the chief advocates. It came when there was a military stalemate on the continent called the "Phoney War". Months of planning at the highest civilian, military, and diplomatic levels in London and Paris, saw multiple reversals and deep divisions.[31] Finally the British and French agreed on a plan that involved uninvited invasions of neutral Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and Denmark's Faroe Islands, with the goals chiefly of damaging the German war economy and also assisting Finland in its war with the Soviet Union. An allied war against the Soviet Union was part of the plan.[32]

The actual Allied goal was not to help Finland but to engage in economic warfare against Germany by cutting off

German invasion 1940

When Germany began its attack on France in May 1940, British troops and French troops again fought side by side, but defeat came quickly. The Royal Navy evacuated 198,000 British and 140,000 French soldiers in the Dunkirk evacuation in late May/early June 1940. Tens of thousands of tanks, trucks, and artillery guns were left behind, as well as countless radios, machine guns, rifles, tents, spare parts, and other gear. The new British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, pledged that the United Kingdom would continue to fight for France's freedom—even if it must do so without France.[35] After Mers el Kebir, Britain recognized Free France as both its ally and the only legitimate French government.

In contrast, the United States formally recognized and established diplomatic relations with Vichy France (until late 1942) and avoided formal relations with the exiled government of de Gaulle and its claim to be the only legitimate government of France. Churchill, caught between the US and de Gaulle, tried to find a compromise.[36][37]

Britain and the Soviet Union

The Anglo-Soviet Agreement was signed in July 1941 allying with the two countries. This was broadened to a political alliance with the Anglo-Soviet Treaty of 1942.

In October 1944 Churchill and his Foreign Minister Anthony Eden met in Moscow with Stalin and his foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. They planned who would control what in postwar Eastern Europe. They agreed to give 90% of the influence in Greece to Britain and 90% in Romania to the USSR. USSR gained an 80%/20% division in Bulgaria and Hungary. There was a 50/50 division in Yugoslavia and no Soviet share in Italy.[38][39]

Middle East

Iraq

Iraq was an independent country in 1939, with a strong British presence, especially in the oil fields. Iraq broke relations with Germany but there was a strong pro-Italian element. The regime of Regent

Iran (Persia)

In 1939 the ruler of

At the

India

Serious tension erupted over American demands that India be given independence, a proposition Churchill vehemently rejected. For years Roosevelt had encouraged Britain's disengagement from India. The American position was based on principled opposition to colonialism, practical concern for the outcome of the war, and the expectation of a large American role in a post-colonial era. However, in 1942 when the Congress Party launched a Quit India Movement, the British authorities immediately arrested tens of thousands of activists, including Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, and imprisoned them until 1945. Meanwhile, India became the main American staging base for aid to China. Churchill threatened to resign if Roosevelt pushed too hard regarding independence, so Roosevelt backed down.[42][43]

British Commonwealth

As the

Britain generally handled the diplomatic relations of the Commonwealth nations. Canada hosted top-level meetings between Britain and the US (the First and Second Quebec Conference), although Canadian representatives only participated in limited bilateral discussions during those summits.[47] As opposed to World War I, the British government, and the governments in the dominions did not form an Imperial War Cabinet, although the establishment of one was proposed by the Australian government in 1941.[47] The proposal was rejected by both Churchill, and Mackenzie King; the former was unwilling to share powers with the dominions, and the latter wanted to maintain the appearance that the dominions have an autonomous foreign policy.[47] Mackenzie King also viewed the formal establishment of an Imperial War Cabinet as unnecessary, believing that contemporary methods of communication and the appointment of high commissioners to the other realms, had already provided the governments with an "invisible imperial cabinet".[47]

Australia

During the war, Australia felt abandoned by London and moved to a close relationship with the US, playing a support role in the American war against Japan. Australian Prime Minister John Curtin stated, "I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom."[48] US President Roosevelt ordered General Douglas MacArthur to move the American base from the Philippines to Brisbane, Australia. By September 1943, more than 120,000 American soldiers were in Australia. The Americans were warmly welcomed but there were some tensions, including the so-called Battle of Brisbane. MacArthur worked very closely with the Australian government and took command of its combat operations.

Fighting continued throughout Southeast Asia for the next two years. MacArthur promoted a policy of "

The Canberra Pact of 1944 between Australia and New Zealand was criticized in the United States.

Canada

Canada's declaration of war drew criticism from some

The need to develop necessary facilities in

As opposed to the United Kingdom, and the other dominions of the British Empire, Canada maintained relations with Vichy France until November 1942.[47] Relations were maintained with Vichy France as the British wanted to maintain an open channel of communication with its government.[47] The Canadian government was involved in a brief diplomatic incident between the Free French, and the United States after Charles de Gaulle captured Saint Pierre and Miquelon from the local Vichy regime.[47] As the territory was nearby Newfoundland, the American government demanded that Canada remove the Free French from the islands, although the Canadians made no efforts to do so.[47] However, the Canadian government did not formally recognize Free France as the legitimate French government until October 1944, during de Gaulle's visit to Montreal.[47]

New Zealand

The Labour Government had been critical of the fascist powers, voicing opposition to the second Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935. During the war, New Zealand assumed responsibility for the defense of some British colonies in the Pacific on behalf of Britain.

The Canberra Pact of 1944 between Australia and New Zealand was criticized in the United States.

South Africa

Italy was poorly prepared for war and increasingly fell under Nazi dictation.[131] After initial success in British Somaliland, Egypt, the Balkans (despite the initial defeat against Greece), and eastern fronts, Italian military efforts failed in North and East Africa,[132] and Germany had to intervene to rescue its neighbor. After the Allies invaded and took Sicily and southern Italy in 1943, the regime collapsed. Mussolini was arrested and the King appointed General Pietro Badoglio as new Prime Minister. They later signed the armistice of Cassibile and banned the Fascist Party. However Germany moved in, with the Fascists' help, occupying Italy north of Naples. German paratroopers rescued Mussolini and Hitler set him up as head of a puppet government the Italian Social Republic, often called the Salò Republic; a civil war resulted. The Germans gave way slowly, for mountainous Italy offered many defensive opportunities.[133]

Britain by 1944 feared that Italy would become a communist state under Soviet influence. It abandoned its original concept of British hegemony in Italy and substituted for it a policy of support for an independent Italy with a high degree of American influence.[134]

Balkans

Hitler, preparing to invade the Soviet Union, diverted attention to make sure the southern or Balkan flank was secure. Romania was under heavy pressure, and had to cede 40,000 square miles of territory with 4 million people to the USSR, Hungary and Bulgaria; German troops came in to protect the vital oil fields (Germany's only source of oil besides the USSR). Romania signed the Axis Pact and became a German ally (November 1940).[135] So too did Hungary (November 1940) and Bulgaria (March, 1941).[136][137]

Greece

In spring 1939, Italy occupied and annexed Albania. Britain tried to deter an invasion by guaranteeing Greece's frontiers. Greece, under the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas, to support the Allies' interests rejected Italian demands. Italy invaded Greece on 28 October 1940, but Greeks repelled the invaders after a bitter struggle (see Greco-Italian War). By mid-December, 1940, the Greeks occupied nearly a quarter of Albania, tying down 530,000 Italian troops. Metaxas tended to favor Germany but after he died in January 1941 Greece accepted British troops and supplies. In March 1941, a major Italian counterattack failed, humiliating Italian military pretensions.[138]

Germany needed to secure its strategic southern flank in preparation for an invasion of the USSR, Hitler reluctantly launched the

Wartime conditions were severe for civilians; famine was rampant as grain production plunged and Germany seized food supplies for its own needs.

Yugoslavia and Croatia

Yugoslavia signed on as a German ally in March 1941, but within days an anti-Nazi coup, led by Serbians with British help, overthrew the prince regent, repudiated the Nazis, and installed the 17-year-old heir as King Peter II.[140]

Germany immediately bombarded the capital

What was left of Yugoslavia became the new

Two major anti-German anti-fascist guerrilla movements emerged, the first in Europe self-organised anti-fascist movement (started in Croatia) partisans led by a Croat Josip Broz Tito had the initial support from the Kremlin. The Chetniks led by the Serbian chetnik Colonel Draža Mihailović was loyal to the royal government in exile based in London. Tito's movement won out in 1945, executed its enemies, and reunited Yugoslavia.[145]

Japan

Japan had conquered all of Manchuria and most of China by 1939 in the

Imperial conquests

Japan launched its own blitzkriegs in East Asia. In 1937, the Japanese Army invaded and captured most of the coastal Chinese cities such as Shanghai. Japan took over French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia), British Malaya (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore) as well as the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Thailand managed to stay independent by becoming a satellite state of Japan. In December 1941 to May 1942, Japan sank major elements of the American, British and Dutch fleets, captured Hong Kong,[149] Singapore, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, and reached the borders of India and began bombing Australia. Japan suddenly had achieved its goal of ruling the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Imperial rule

The ideology of Japan's colonial empire, as it expanded dramatically during the war, contained two contradictory impulses. On the one hand, it preached the unity of the

The Japanese government established puppet regimes in Manchuria ("Manchukuo") and China proper; they vanished at the end of the war. The Japanese Army operated ruthless governments in most of the conquered areas, but paid more favorable attention to the Dutch East Indies. The main goal was to obtain oil, but Japan sponsored an Indonesian nationalist movement under Sukarno.[153] Sukarno finally came to power in the late 1940s after several years of battling the Dutch.[154] The Dutch destroyed their oil wells but the Japanese reopened them. However most of the tankers taking oil to Japan were sunk by American submarines, so Japan's oil shortage became increasingly acute.[155]

Puppet states in China

Japan set up puppet regimes in Manchuria ("Manchukuo") and China proper; they vanished at the end of the war.[156]

Manchuria, the historic homeland of the

When Japan seized control of China proper in 1937–38, the Japanese

Military defeats

The attack on Pearl Harbor initially appeared to be a major success that knocked out the American battle fleet—but it missed the aircraft carriers that were at sea and ignored vital shore facilities whose destruction could have crippled US Pacific operations. Ultimately, the attack proved a long-term strategic disaster that actually inflicted relatively little significant long-term damage while provoking the United States to seek revenge in an all-out total war in which no terms short of unconditional surrender would be entertained.

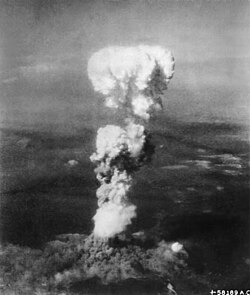

However, as Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto warned, Japan's six-month window of military advantage following Pearl Harbor ended with the Imperial Japanese Navy's offensive ability being crippled at the hands of the American Navy in the Battle of Midway. As the war became one of mass production and logistics, the US built a far stronger navy with more numerous warplanes, and a superior communications and logistics system. The Japanese had stretched too far and were unable to supply their forward bases—many soldiers died of starvation. Japan built warplanes in large quantity but the quality plunged, and the performance of poorly trained pilots spiraled downward.[160] The Imperial Navy lost a series of major battles, from Midway (1942) to the Philippine Sea (1944) and Leyte Gulf (1945), which put American long-range B-29 bombers in range. A series of massive raids burned out much of Tokyo and 64 major industrial cities beginning in March 1945 while Operation Starvation seriously disrupted the nation's vital internal shipping lanes. Regardless of how the war was becoming hopeless, the circle around the Emperor held fast and refused to open negotiations. Finally in August, two atomic bombs and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria demonstrated the cause was futile, and Hirohito authorized a surrender whereby he kept his throne.[161]

Deaths

Total Japanese military fatalities between 1937 and 1945 were 2.1 million; most came in the last year of the war. Starvation or malnutrition-related illness accounted for roughly 80 percent of Japanese military deaths in the Philippines, and 50 percent of military fatalities in China. The aerial bombing of a total of 65 Japanese cities appears to have taken a minimum of 400,000 and possibly closer to 600,000 civilian lives (over 100,000 in Tokyo alone, over 200,000 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and 80,000–150,000 civilian deaths in the battle of Okinawa). Civilian death among settlers who died attempting to return to Japan from Manchuria in the winter of 1945 were probably around 100,000.[162]

Finland

Finland

The August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union contained a secret protocol dividing much of eastern Europe and assigning Finland to the Soviet sphere of influence. Finland before 1918 had been a Grand Duchy [165] of Russia, and many Finnish speakers lived in neighboring parts of the Soviet Union. After unsuccessfully attempting to force territorial and other concessions on the Finns, the Soviet Union invaded Finland in November 1939 starting the Winter War. Finland won very wide popular support in Britain and the United States.[166]

Soviet success in Finland would threaten Germany's iron-ore supplies and offered the prospect of Allied interference in the region. The Soviets overwhelmed the Finnish resistance in the

Following the Winter War, Finland sought protection and support from Britain and Sweden without success. Finland drew closer to Germany, first with the intent of enlisting German support as a counterweight to thwart continuing Soviet pressure, and later to help regain lost territories. Finland declared war against the Soviet Union on 25 June 1941 in what is called the "Continuation War" in Finnish historiography.[168] To meet Stalin's demands, Britain reluctantly declared war on Finland on 6 December 1941, although no other military operations followed. War was never declared between Finland and the United States, though relations were severed between the two countries in 1944 as a result of the Ryti–Ribbentrop Agreement. The arms-length collaboration with Germany stemmed from a precarious balance struck by the Finns in order to avoid antagonizing Britain and the United States. In the end Britain declared war to satisfy the needs of its Soviet policy, but did not engage in combat against Finland. Finland concluded armistice negotiations with the USSR under strong German pressure to continue the war, while British and American acted in accord with their own alliances with the Soviets.[169]

Finland maintained command of its armed forces and pursued war objectives independently of Germany. Germans and Finns did work closely together during

After Soviet offensives were fought to a standstill, in 1944 Ryti's successor as president, Marshall Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, opened negotiations with the Soviets, which resulted in the Moscow Armistice on 19 September 1944. Under its terms Finland was obliged to remove or intern any remaining German troops on Finnish territory past September 15. This resulted in a military campaign to expel German forces in Lapland in the final months of 1944. Finland signed a peace treaty with the Allied powers in 1947.

Hungary

Hungary was a reluctant ally of Germany in the war.

While waging war against the

Romania

Following the start of the war on 1 September 1939, the

In summer 1940 a series of territorial disputes were diplomatically resolved unfavorably to Romania, resulting in the loss of most of the territory gained in the wake of World War I. This caused the popularity of Romania's government to plummet, further reinforcing the fascist and military factions, who eventually staged a coup that turned the country into a dictatorship under

After the tide of war turned against Germany Romania was

Neutrals

The main neutrals were Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey.[179]

The Soviet Union was officially neutral until June 1941 in Europe, and until August 1945 in Asia, when it attacked Japan in cooperation with the US.

Latin America

The US believed, falsely, that Germany had a master plan to subvert and take control of the economy of much of South America. Washington made anti-Nazi activity a high priority in the region. By July 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt authorized the creation of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) in response to perceived propaganda efforts in Latin America by Germany and Italy. Through the use of news, film and radio broadcast media in the United States, Roosevelt sought to enhance his Good Neighbor policy, promote Pan-Americanism and forestall military hostility in Latin America through the use of cultural diplomacy.[180][181] Three countries actively joined the war effort, while others passively broke relations or nominally declared war.[182] Cuba declared war in December 1941 and actively helped in the defence of the Panama Canal. It did not send forces to Europe. Mexico declared war on Germany in 1942 after U-boats sank Mexican tankers carrying crude oil to the United States. It sent a 300-man fighter squadron to the war against Japan in 1945.[183] Brazil declared war against Germany and Italy on 22 August 1942 and sent a 25,700-man infantry force that fought mainly on the Italian Front, from September 1944 to May 1945. Its Navy and Air Force acted in the Atlantic Ocean.[184]

Argentina

The Argentine government remained neutral until the last days of the war but quietly tolerated entry of Nazi leaders fleeing Germany, Belgium and Vichy France in 1945. Indeed, a conspiracy theory grew up after the war that greatly exaggerated the Nazi numbers and amount of gold they brought. Historians have shown there was little gold and probably not many Nazis, but the myths live on.[187][188]

Baltic states

Despite declaring neutrality the Baltic states were secretly assigned to the

Ireland

Ireland tried to be strictly neutral during the war, and refused to allow Britain to use bases. However it had large sales of exports to Britain, and tens of thousands joined the British armed forces.[189]

Portugal

Portugal controlled strategically vital

Spain

Nazi leaders spent much of the war attempting to persuade the

Spain was neutral and traded as well with the Allies. Germany had an interest in seizing the key fortress of Gibraltar, but Franco stationed his army at the French border to dissuade Germany from occupying the Iberian Peninsula. Franco displayed pragmatism and his determination to act principally in Spanish interests, in the face of Allied economic pressure, Axis military demands, and Spain's geographic isolation. As the war progressed he became more hard-line toward Germany and more accommodating to the Allies.[196]

Sweden

At the outbreak of war between Germany and Poland, Britain and France in September 1939, Sweden declared neutrality. At outbreak of war in November between Finland and the Soviet Union, Sweden declared "Non-belligerent" to make it possible to support Finland with arms and volunteers in the Winter War. From 13 December to the end of the war, a national unity government under Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson and Foreign Minister Christian Günther was formed that included all major parties in the Riksdag.

From April 1940 Sweden and Finland was encircled between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and subject to both British and German

As a free country, Sweden took in refugees from Finland, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic states. During the last part of the war, it was possible to save some victims from German concentration camps.

Switzerland

Switzerland was neutral and did business with both sides. It mobilized its army to defend itself against any invasion. The

Swiss banks paid Germany 1.3 billion Swiss Francs for gold; Germany used the Francs to buy supplies on the world market. However much of the gold was looted and the Allies warned Switzerland during the war. In 1947 Switzerland paid 250 million francs in exchange for the dropping of claims relating to the Swiss role in the gold transactions.[201]

Switzerland took in 48,000 refugees during the war, of whom 20,000 were Jewish. They also turned away about 40,000 applicants for refugee status.[202][203]

Switzerland's role regarding Nazi Germany became highly controversial in the 1990s.[204] Wylie says, "Switzerland has been widely condemned for its part in the war. It has been accused of abetting genocide, by refusing to offer sanctuary to Hitler's victims, bankrolling the Nazi war economy, and callously profiting from Hitler's murderous actions by seizing the assets of those who perished in the death camps."[205][206] On the other hand, Churchill told his foreign minister in late 1944:

Of all the neutrals, Switzerland has the great right to distinction. She has been the sole international force linking the hideous-sundered nations and ourselves. What does it matter whether she has been able to give us the commercial advantages we desire or has given too many to the German, to keep herself alive? She has been a democratic state, standing for freedom in self defence among her mountains, and in thought, despite of race, largely on our side.[207]

Turkey

Turkey was neutral in the war, but signed a treaty with Britain and France in October 1939 that said the Allies would defend Turkey if Germany attacked it. The deal was enhanced with loans of £41 million. An invasion was threatened in 1941 but did not happen and Ankara refused German requests to allow troops to cross its borders into Syria or into the USSR. Germany had been its largest trading partner before the war, and Turkey continued to do business with both sides. It purchased arms from both sides. The Allies tried to stop German purchases of chrome (used in making better steel). Starting in 1942 the Allies provided military aid and pressed for a declaration of war. Turkey's president conferred with Roosevelt and Churchill at the Cairo Conference in November, 1943, and promised to enter the war when it was fully armed. By August 1944, with Germany nearing defeat, Turkey broke off relations. In February 1945, it declared war on Germany and Japan, a symbolic move that allowed Turkey to join the future United Nations. Meanwhile, relations with Moscow worsened, setting stage for the Truman Doctrine of 1947 and the start of the Cold War.[208]

Governments in exile

Britain welcomed governments in exile to set up their headquarters in London[209] whilst others were set up in neutral or other allied territory. Recognition for these bodies would vary and change over time.

Poland: in exile and underground

When the Polish forces were demolished by Germany in the first three weeks of September 1939, the government vanished and most Polish leaders

The

Since the start of the war the body protested on the international stage against the German occupation of their territory and the treatment of their civilian population. In 1940 the Polish Ministry of Information produced a list of those it believed had been murdered by the Nazis. On 10 December 1942, the Polish government-in-exile published a 16-page report addressed to the Allied governments, titled The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland.[note 1] The report contained eight pages of Raczyński's Note, which was sent to foreign ministers of 26 governments who signed the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942.[213]

Norway

After Germany swept to control in April 1940, the government in exile, including the royal family, was based in London. Politics were suspended and the government coordinated action with the Allies, retained control of a worldwide diplomatic and consular service, and operated the huge Norwegian merchant marine. It organized and supervised the resistance within Norway. One long-term impact was the abandonment of a traditional Scandinavian policy of neutrality; Norway became a founding member of NATO in 1949.[214] Norway at the start of the war had the world's fourth largest merchant fleet, at 4.8 million tons, including a fifth of the world's oil tankers. The Germans captured about 20% of the fleet but the remainder, about 1000 ships, were taken over by the government. Although half the ships were sunk, the earnings paid the expenses of the government.[215][216]

Netherlands

The government in 1940 fled to London, where it had command of some colonies as well as the Dutch navy and merchant marine.

Czechoslovakia

The

Belgium

The German invasion lasted only 18 days in 1940 before the Belgian army surrendered. The king remained behind, but the government escaped to France and then to England in 1940. Belgium was liberated in late 1944.[221]

Belgium had two holdings in Africa, the very large colony of the

Yugoslavia in exile

Yugoslavia had a weak government in exile based in London that included

Korea

Based in the Chinese city of

List of all war declarations and other outbreaks of hostilities

Regarding type of war outbreak (fourth column):

- A : Attack without a declaration of war

- U : State of war emerged through ultimatum

- WD : State of war emerged after formal declaration of war

- D : Diplomatic breakdown leading to a state of war. In some cases a diplomatic breakdown later led to a state of war. Such cases are mentioned in the comments.

| Date | Attacking Nation(s) | Attacked Nation(s) | Type | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939-09-01 | Germany | Poland | A | |

| 1939-09-03 | United Kingdom, France | Germany | U | See British declaration of war on Germany (1939), French declaration of war on Germany (1939) |

| 1939-09-03 | Australia, New Zealand | Germany | WD | |

| 1939-09-06 | South Africa | Germany | WD | |

| 1939-09-10 | Canada | Germany | WD | |

| 1939-09-17 | Soviet Union | Poland | A | |

| 1939-11-30 | Soviet Union | Finland | A | Diplomatic breakdown day before |

| 1940-04-09 | Germany | Denmark, Norway | A | |

| 1940-05-15 | Germany | Belgium, Netherlands | WD | The German offensive in western Europe |

| 1940-06-10 | Italy | France, United Kingdom | WD | At a time when France already was about to fall |

| 1940-06-10 | Canada | Italy | WD | |

| 1940-06-11 | South Africa, Australia, New Zealand | Italy | WD | |

| 1940-06-12 | Egypt | Italy | D | |

| 1940-07-04 | United Kingdom | France* | A | Vichy France Navy and colonies were attacked by UK, but no war was declared |

| 1940-10-28 | Italy | Greece | U | |

| 1941-04-06 | Germany | Greece | WD | |

| 1941-04-06 | Germany, Bulgaria | Yugoslavia | A | |

| 1941-04-06 | Italy | Yugoslavia | WD | |

| 1941-04-23 | Greece | Bulgaria | D | |

| 1941-06-22 | Germany*, Italy, Romania | Soviet Union | WD | *The German declaration of war was given at the time of the attack[225] |

| 1941-06-24 | Denmark | Soviet Union | D | Denmark was occupied by Germany |

| 1941-06-25 | Finland | Soviet Union | A | Second war between these nations |

| 1941-06-27 | Hungary | Soviet Union | D | Diplomatic breakdown 1941-06-24 |

| 1941-06-30 | France | Soviet Union | D | |

| 1941-12-07 | United Kingdom | Romania, Hungary, Finland | U | Diplomatic breakdowns 1941-02-11,1941-04-07 and 1941-08-01 |

| 1941-12-07 | Japan | Thailand, British Empire, United States | A | WD came the day after |

| 1941-12-08 | Japan | United States, British Empire | WD | See Japanese declaration of war on the United States and the British Empire |

| 1941-12-08 | United Kingdom | Japan | WD | See United Kingdom declaration of war on Japan

|

| 1941-12-08 | United States | Japan | WD | See United States declaration of war on Japan |

| 1941-12-08 | Canada, the Netherlands, South Africa | Japan | WD | |

| 1941-12-09 | China | Germany*, Italy*, Japan | WD | *Diplomatic breakdown 1941-07-02 |

| 1941-12-09 | Australia, New Zealand | Japan | WD | |

| 1941-12-11 | Germany, Italy | United States | WD | See German declaration of war against the United States and Italian declaration of war on the United States |

| 1941-12-11 | United States | Germany, Italy | WD | See United States declaration of war upon Germany and United States declaration of war on Italy |

| 1941-12-12 | Romania | United States | WD | |

| 1941-12-13 | Bulgaria | United Kingdom, United States | WD | |

| 1941-12-15 | Hungary | United States | WD | |

| 1942-01-24 | United States | Denmark | D | |

| 1942-05-28 | Mexico | Germany, Italy, Japan | WD | See Mexican declaration of war on Germany, Italy, and Japan Diplomatic breakdowns in all three cases 1941 |

| 1942-08-22 | Brazil | Germany, Italy | WD | Diplomatic breakdowns 1942-01-20 and 1942-01-28 |

| 1942-11-09 | France | United States | D | |

| 1943-01-20 | Chile | Germany, Japan, Italy | D | |

| 1943-09-09 | Iran | Germany | WD | Diplomatic breakdown in 1941 |

| 1943-10-13 | Italy | Germany | WD | After the fall of Mussolini, Italy changed side |

| 1944-01-10 | Argentina | Germany, Japan | D | |

| 1944-06-30 | United States | Finland | D | |

| 1944-08-04 | Turkey | Germany | D | Turkey declared war on Germany on 23 Feb. 1945; a state of war against Germany existed from this date |

| 1944-08-23 | Romania | Germany | WD | Like Italy, Romania also changed side. |

| 1944-09-05 | Soviet Union | Bulgaria | WD | |

| 1944-09-07 | Bulgaria | Germany | D | |

| 1945-02-24 | Egypt | Germany*, Japan | WD | *Diplomatic breakdown already 1939 |

| 1945 | Argentina, Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela, Uruguay, Syria, and Saudi Arabia | Germany | WD | Needed a declaration to be eligible to join United Nations |

| 1945-04-03 | Finland | Germany | WD | Diplomatic breakdown in 1944, last outbreak in Europe |

| 1945-07-06 | Brazil | Japan | WD | |

| 1945-07-17 | Italy | Japan | WD | |

| 1945-08-08 | Soviet Union | Japan | WD | Last outbreak of war during the Second World War |

Main source: Swedish encyklopedia "Bonniers Lexikon" 15 volumes from the 1960s, article "Andra Världskriget" ("The Second World War"), volume 1 of 15, table in columns 461–462. (Each page are in two columns, numbering of columns only)

See also

- Causes of World War II

- Cold War

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- European foreign policy of the Chamberlain ministry

- Foreign policy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration

- Germany–Soviet Union relations, 1918–1941

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Military production during World War II

Notes

- ^ See: Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (10 December 1942), The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland, note to the governments of the United Nations.

References

- Citations

- ISBN 978-1-61787-205-1.

the most important of the Allied leaders during the first half of World War II

- ^ "The Big Three". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ Sainsbury, Keith (1986). The Turning Point: Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-Shek, 1943: The Moscow, Cairo, and Teheran Conferences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Herbert Feis, Churchill Roosevelt Stalin: The War They Waged and the Peace They Sought: A Diplomatic History of World War II (1957)

- ^ William Hardy McNeill, America, Britain and Russia: their co-operation and conflict, 1941–1946 (1953)

- ISBN 978-94-011-9199-9, archived from the original on 2021-07-23, retrieved 2020-11-22)

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help - ^ John F. Shortal, Code Name Arcadia: The First Wartime Conference of Churchill and Roosevelt (Texas A&M University Press, 2021).

- ^ Stoler, Mark A. "George C. Marshall and the "Europe-First" Strategy, 1939–1951: A Study in Diplomatic as well as Military History" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1317864714. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ISBN 9780824070298. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ISBN 978-0385353069. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-07-02.

- ^ ISBN 9781135071028. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ^ Gray, Anthony W. Jr. (1997). "Chapter 6: Joint Logistics in the Pacific Theater". In Alan Gropman (ed.). The Big 'L' — American Logistics in World War II. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. Archived from the original on 2010-04-14. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- S2CID 153563648.

- ^ Fraser J. Harbutt, Yalta 1945: Europe and America at the Crossroads (2010).

- ^ Herbert Feis, Between War and Peace: The Potsdam Conference (1960).

- ^ Townsend Hoopes, and Douglas Brinkley, FDR and the Creation of the UN (Yale UP, 1997).

- ^ Richard W. Van Alstyne, "The United States and Russia in World War II: Part I" Current History 19#111 (1950), pp. 257-260 online

- ^ Gaddis 1972, p. 27.

- ^ 1946-47 Part 1: The United Nations. Section 1: Origin and Evolution.Chapter E: The Dumbarton Oaks Conversations. The Yearbook of the United Nations. United Nations. p. 6. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "1944–1945: Dumbarton Oaks and Yalta". www.un.org. 2015-08-26. Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. "The United States and the Founding of the United Nations, August 1941 – October 1945". 2001-2009.state.gov. Archived from the original on 2005-10-23. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ "1945: The San Francisco Conference". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ W.K. Hancock and M. M. Gowing, British War Economy (1949) p. 227 online Archived 2012-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leo T. Crowley, "Lend Lease" in Walter Yust, ed. 10 Eventful Years (1947)1:520, 2, pp. 858–60. There had been loans before the Lend lease was enacted; these were repaid.

- ^ John Reynolds, Rich Relations: The American Occupation of Britain, 1942–45 (Random House, 1995)

- JSTOR 1985768.

- ISBN 9781852855970. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Gordon F. Sander, The Hundred Day Winter War (2013) pp 4–5.

- ISBN 9781469640143. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ Bernard Kelly, "Drifting Towards War: The British Chiefs of Staff, the USSR and the Winter War, November 1939 – March 1940", Contemporary British History 23.3 (2009): 267–291.

- ^ J. R. M. Butler, History of Second World War: Grand strategy, volume 2: September 1939 – June 1941 (1957) pp 91–150. online free

- ^ Butler, p 97

- ^ Erin Redihan, "Neville Chamberlain and Norway: The Trouble with 'A Man of Peace' in a Time of War", New England Journal of History (2013) 69#1/2 pp 1–18.

- ^ Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (1994) pp 130–31, 142–161

- ^ a b Milton Viorst, Hostile allies: FDR and Charles de Gaulle (1967)

- ^ a b David G. Haglund, "Roosevelt as 'Friend of France'—But Which One?", Diplomatic History (2007) 31#5 pp: 883–908.

- JSTOR 1862322.

- ^ Klaus Larres, A companion to Europe since 1945 (2009) p. 9

- ISBN 9781841769912. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-20. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- JSTOR 3018096.

- ^ Eric S. Rubin, "America, Britain, and Swaraj: Anglo-American Relations and Indian Independence, 1939–1945", India Review (2011) 10#1 pp 40–80

- ISBN 9780553804638. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-01-11. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ "South Africa: World War II". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2019. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ "Mackenzie King addresses Canadians as Britain declares war on Germany". CBC Archives. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2018. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780199271641. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-21. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "1939–1945: The World at War". Canada and the World: A History. Global Affairs Canada. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780199589937. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-04. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ISBN 9781107470880. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-13. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ ISBN 0-7425-0785-8.

- ISBN 978-1-5548-8992-1.

- ^ Fehrenbach, T. R. (1967). F. D. R.'s Undeclared War, 1939-1941. D. McKay Co. p. 103.

- LCCN 59-60001. Archived from the originalon 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Andrew Stewart, "The British Government and the South African Neutrality Crisis, 1938–39", The English Historical Review (2008) 23# 503, pp 947–972

- ISBN 9780465054763. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ISBN 9780801462573. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Robert Dallek, Franklin D. Roosevelt and American foreign policy, 1932–1945 (1995) pp 232, 319, 373

- ISBN 9780719040580. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Woolner, David B.; et al., eds. (2008), FDR's world: war, peace, and legacies, p. 77

- ^ James MacGregor Burns, Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom (1970) pp 180–85

- ^ David M. Gordon, "The China–Japan War, 1931–1945", The Journal of Military History (2006) v 70#1, pp 137–82. online Archived 2020-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Schaller, U.S. Crusade in China, 1938–1945 (1979)

- ^ Martha Byrd, Chennault: Giving Wings to the Tiger (2003)

- ^ The official Army history notes that 23 July 1941 Roosevelt "approved a Joint Board paper which recommended that the United States equip, man, and maintain the 500-plane Chinese Air Force proposed by Currie. The paper suggested that this force embark on a vigorous program to be climaxed by the bombing of Japan in November 1941." Lauchlin Currie was the White House official dealing with China. Charles F. Romanus and Riley Sunderland, U.S. Army in World War II: China-Burma-India Theater: Stillwell's Mission to China (1953) p. 23 online Archived 2013-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- JSTOR 2712474.

- ^ Alan Armstrong, Preemptive Strike: The Secret Plan That Would Have Prevented the Attack on Pearl Harbor (2006) is a popular version

- ^ Romanus and Sunderland. Stilwell's Mission to China (1953), chapter 1 online edition Archived 2013-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Romanus and Sunderland. Stilwell's Mission to China p. 20 online Archived 2013-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See Laura Tyson Li, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek: China's Eternal First Lady (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006).

- ISBN 9780307595881.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

- ^ Odd Arne Westad, Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950 (2003)

- ^ Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004)

- ^ Geoffrey Roberts, Molotov: Stalin's Cold Warrior (2012)

- ISBN 9781136339523. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala et al. eds. Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment (Yale University Press, 2008).

- ^ B. Farnborough, "Marxists in the Second World War", Labour Review, Vol. 4 No. 1, April–May 1959, pp. 25–28 Archived 2015-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 159466422.

- ^ William Hardy McNeill, America, Britain, and Russia: their co-operation and conflict, 1941–1946 (1953)

- ^ Richard J. Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia (2004)

- ^ Joel Blatt (ed), The French Defeat of 1940 (Oxford, 1998)

- ^ Marc Olivier Baruch, "Charisma and Hybrid Legitimacy in Pétain's État français (1940‐44)", Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 7.2 (2006): 215–224.

- ^ William L. Langer, Our Vichy Gamble (1947) pp 89–98.

- S2CID 162269165.

- ISBN 978-0415321679

- ^ William Langer, Our Vichy gamble (1947)

- ISBN 9781107031265. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- S2CID 159589846.

- ^ Martin Thomas, "The Discarded Leader: General Henri Giraud and the Foundation of the French Committee of National Liberation", French History (1996) 10#12 pp 86–111

- ISBN 978-0-00-711622-5.

- ^ Martin Thomas, "Deferring to Vichy in the Western Hemisphere: The St. Pierre and Miquelon Affair of 1941", International History Review (1997) 19#4 pp 809–835.online Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jean Lacouture, DeGaulle: The Rebel, 1890–1944 (1990) pp 515–27

- ^ Carl Boyd, Hitler's Japanese Confidant: General Oshima Hiroshi and Magic Intelligence, 1941–1945 (2002)

- ^ Mark Mazower, Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe (2009) ch 9

- ^ Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (2005) p 414

- ISBN 9781845450472. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Richard L. DiNardo, "The dysfunctional coalition: The axis powers and the eastern front in World War II", The Journal of Military History (1996) 60#4 pp 711–730

- ^ Richard L. DiNardo, Germany and the Axis Powers: From Coalition to Collapse (2005)

- ^ Facts on File World News Digest (August 31, 1943)

- ^ Mark Mazower, Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe (2008) ch 9

- ^ Ulrich Herbert, Hitler's Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labour in Germany Under the Third Reich (1997)

- S2CID 159846665.

- ^ Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction (2007) pp. 476–85, 538–49.

- ISBN 9781611456479. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ A Ridiculous Hundred Million Slavs: Concerning Adolf Hitler's World-View, Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History Polish Academy of Sciences, Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza page 49, Warsaw 2017

- ^ A Ridiculous Hundred Million Slavs: Concerning Adolf Hitler's World-View, Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History Polish Academy of Sciences, Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza pages 91–92, Warsaw 2017

- ^ Stutthof: hitlerowski obóz koncentracyjny Konrad Ciechanowski Wydawnictwo Interpress 1988, page 13"

- ^ T. Snyder, Bloodlands, Europe between Hitler and Stalin, Vintage, (2011). p. 65

- JSTOR 41549951.

- ^ John Lukacs, The Last European War: September 1939 – December 1941 p. 31

- ISBN 9780191613555. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ a b "Avalon Project: The French Yellow Book: No. 113 – M. Coulondre, French Ambassador in Berlin, to M. Georges Bonnet, Minister for Foreign Affairs. Berlin, April 30, 1939". Archived from the original on August 20, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-521-52938-9. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2009-06-16 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 9780393322521. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ A Ridiculous Hundred Million Slavs: Concerning Adolf Hitler's World-View, Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History Polish Academy of Sciences, Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza page 111, Warsaw 2017

- ^ Zara Steiner, The Triumph of the Dark: European International History, 1933–1939 (2011) pp 690–92, 738–41

- ISBN 9780434842162. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Richard Overy, The Road to War: the Origins of World War II (1989) pp 1–20

- ^ Kochanski, The Eagle Unbowed (2012) p 52

- ^ Martin Gilbert, The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust (2004).

- ^ Simone Gigliotti, and Hilary Earl, eds. A Companion to the Holocaust (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

- ^ Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War (1985).

- ^ Tony Kushner, "'Pissing in the Wind'? The Search for Nuance in the Study of Holocaust 'Bystanders'", Journal of Holocaust Education 9.2 (2000): 57–76.

- ^ Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman, FDR and the Jews (2013) p. 318–319. The authors also argue: "Roosevelt played no apparent role in the decision not to bomb Auschwitz. Even if the matter had reached his desk, however, he would not likely have contravened his military. Every major American Jewish leader and organization that he respected remained silent on the matter, as did all influential members of Congress and opinion-makers in the mainstream media." p. 321.

- ^ Bengt Jangfeldt, The Hero of Budapest: The Triumph and Tragedy of Raoul Wallenberg (2014) excerpt Archived 2021-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Béla Bodó, "Caught between Independence and Irredentism: The 'Jewish Question' in the Foreign Policy of the Kállay Government, 1942–1944", Hungarian Studies Review 43.1–2 (2016): 83–126.

- JSTOR 23922991.

- ^ "Selahattin Ülkümen — Turkey". Yad Vashem.

- ^ Philip Morgan, The Fall of Mussolini: Italy, the Italians, and the Second World War (2007)

- ^ Langer and Gleason, Challenge to Isolation, 1:460-66, 502–8

- ^ MacGregor Knox, Common Destiny: Dictatorship, Foreign Policy, and War in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany (2000)

- ^ H. James Burgwyn, Empire on the Adriatic: Mussolini's Conquest of Yugoslavia, 1941–1943 (2005)

- ^ D. Mack Smith, Modern Italy: A Political History (1997)

- ^ Moshe Gat, "The Soviet Factor in British Policy towards Italy, 1943–1945", Historian (1988) 50#4 pp 535–557

- ^ Dennis Deletant, Hitler's Forgotten Ally: Ion Antonescu and his Regime, Romania, 1940–1944 (2006)

- ^ Joseph Held, ed. The Columbia History of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century (1992)

- S2CID 144699901.

- S2CID 159955930.

- ^ Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44 (2001).

- ^ John R. Lampe, Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country (2nd ed. 2000) pp 201–232.

- ^ Steven Pavlowitch, Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia (2008) excerpt and text search Archived 2017-01-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tomislav Dulić, "Mass killing in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945: a case for comparative research", Journal of Genocide Research 8.3 (2006): 255–281.

- ^ "Croatia" (PDF). Shoah Resource Center – Yad Vashem. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Paul Bookbinder, "A Bloody Tradition: Ethnic Cleansing in World War II Yugoslavia", New England Journal of Public Policy 19#2 (2005): 8+ online Archived 2018-03-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Walter R. Roberts, Tito, Mihailović, and the allies, 1941–1945 (1987).

- ^ Herbert Feis, China Tangle: The American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission (1953) contents[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dorothy Borg, The United States and the Far Eastern crisis of 1933–1938 (1964) ch 2

- ^ Haruo Tohmatsu and H. P. Willmott, A Gathering Darkness: The Coming of War to the Far East and the Pacific (2004)

- ^ Oliver Lindsay, The Battle for Hong Kong, 1941–1945: Hostage to Fortune (2009)

- ^ Jon Davidann, "Citadels of Civilization: U.S. and Japanese Visions of World Order in the Interwar Period", in Richard Jensen, et al. eds., Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century (2003) pp 21–43

- Ronald Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan (1985) pp 42, 62–64

- ^ Aaron Moore, Constructing East Asia: Technology, Ideology, and Empire in Japan's Wartime Era, 1931–1945 (2013) pp 226–27

- ^ Laszlo Sluimers, "The Japanese military and Indonesian independence", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (1996) 27#1 pp 19–36

- ^ Bob Hering, Soekarno: Founding Father of Indonesia, 1901–1945 (2003)

- ISBN 9781603587433. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote, Japanese-Sponsored Governments in China, 1937–1945 (1954)

- ^ Prasenjit Duara, Sovereignty and Authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian Modern (2004)

- ^ Gerald E. Bunker, Peace Conspiracy: Wang Ching-wei and the China War, 1937–41 (1972)

- ^ David P. Barrett and Larry N. Shyu, eds. Chinese Collaboration with Japan, 1932–1945: The Limits of Accommodation (2001)

- ^ Eric M Bergerud, Fire In The Sky: The Air War In The South Pacific (2001)

- ^ Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the making of modern Japan (2001) pp. 487–32

- ^ John Dower "Lessons from Iwo Jima". Perspectives (2007). 45 (6): 54–56. online Archived 2011-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vehviläinen, Olli (2002). Finland in the Second World War. Palgrave-Macmillan.

- ^ Henrik O. Lunde, Finland's War of Choice: The Troubled German-Finnish Alliance in World War II (2011)

- ^ "Frontpage – Finland abroad". Greece. Archived from the original on 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ Kent Forster, "Finland's Foreign Policy 1940–1941: An Ongoing Historiographic Controversy", Scandinavian Studies (1979) 51#2 pp 109–123

- ^ Max Jakobson, The Diplomacy of the Winter War: An Account of the Russo-Finnish War, 1939–1940 (1961)

- ^ Mauno Jokipii. "Finland's Entrance into the Continuation War", Revue Internationale d'Histoire Militaire (1982), Issue 53, pp 85–103.

- ^ Tuomo Polvinen, "The Great Powers and Finland 1941–1944", Revue Internationale d'Histoire Militaire (1985), Issue 62, pp 133–152.

- ISBN 9780312311001. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-13. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Stephen D. Kertesz, Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary Between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia (U of Notre Dame Press, 1953).

- ^ Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine John F. Montgomery, Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite. Devin-Adair Company, New York, 1947. Reprint: Simon Publications, 2002.

- S2CID 143248398.

- JSTOR 42555310.

- JSTOR 42554767.

- ^ U.S. government Country study: Romania Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, c. 1990.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Mark Axworthy, Cornel Scafeş and Cristian Crăciunoiu, Third Axis Fourth Ally: Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941–1945, page 9

- ^ Liliana Saiu, Great Powers & Rumania, 1944–1946: A Study of the Early Cold War Era (HIA Book Collection, 1992).

- ^ Neville Wylie, European Neutrals and Non-Belligerents During the Second World War (2002).

- (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-11-08.

- ^ Errol D. Jones, "World War II and Latin America", in Loyd Lee, ed. World War II in Europe, Africa, and the Americas, with General Sources: A Handbook of Literature and Research (1997) pp 415–37

- ^ Thomas M. Leonard, and John F. Bratzel, eds. Latin America During World War II (2007)

- Frank D. McCann, "Brazil, the United States, and World War II", Diplomatic History (1979) 3#1 pp 59–76.

- ^ Jürgen Müller, Nationalsozialismus in Lateinamerika: Die Auslandsorganisation der NSDAP in Argentinien, Brasilien, Chile und Mexiko, 1931–1945 (1997) 567pp.

- JSTOR 174890.

- ^ Ronald C. Newton, The "Nazi Menace" in Argentina, 1931–1947 (Stanford U.P., 1992)

- ^ Daniel Stahl, "Odessa und das 'Nazigold' in Südamerika: Mythen und ihre Bedeutungen' ["Odessa and "Nazi Gold" in South America: Myths and Their Meanings"] Jahrbuch fuer Geschichte Lateinamerikas (2011), Vol. 48, pp 333–360.

- ^ Robert Fisk, In Time of War: Ireland, Ulster and the Price of Neutrality 1939–1945 (1996)

- ^ William Gervase Clarence-Smith, "The Portuguese Empire and the 'Battle for Rubber' in the Second World War", Portuguese Studies Review (2011), 19#1 pp 177–196

- ^ Douglas L. Wheeler, "The Price of Neutrality: Portugal, the Wolfram Question, and World War II", Luso-Brazilian Review (1986) 23#1 pp 107–127 and 23#2 pp 97–111

- ^ Donald G. Stevens, "World War II Economic Warfare: The United States, Britain, and Portuguese Wolfram", Historian 61.3 (1999): 539–556.

- ^ Sonny B. Davis, "Salazar, Timor, and Portuguese Neutrality in World War II", Portuguese Studies Review (2005) 13#1 pp 449–476.

- ^ William Howard Wriggins, Picking up the Pieces from Portugal to Palestine: Quaker Refugee Relief in World War II (2004).

- ^ Michael Mazower, Hitler's Empire, Nazi rule in Occupied Europe (2009) pp. 114–5, 320

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany, and World War II (2009) excerpt and text search Archived 2016-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Gilmour, Sweden, the Swastika, and Stalin: The Swedish Experience in the Second World War (2011) pp 270–71

- ^ Klaus Urner, Let's Swallow Switzerland: Hitler's Plans against the Swiss Confederation (2001)

- S2CID 159802339.

- ^ Stephen Halbrook, Swiss and the Nazis: How the Alpine Republic Survived in the Shadow of the Third Reich (2010) ch 12

- ISBN 9780788145360. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-13. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ISBN 9781136756702. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-02. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Halbrook, Swiss and the Nazis ch 9

- ^ Angelo M. Codevilla, Between the Alps and a Hard Place: Switzerland in World War II and the Rewriting of History, (2013) excerpt and text search Archived 2013-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9780198206903. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-06-09. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ A recent example of the expose literature is Adam LeBor, Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World (2013)

- ISBN 9780719050695. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- JSTOR 3017044.

- ISBN 9781571815033. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-11. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Bernadeta Tendyra, The Polish Government in Exile, 1939–45 (2013)

- ^ Halik Kochanski, The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War (2014), ch .11–14.

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland (2006) pp. 264–265.

- ^ Engel (2014)

- ^ Erik J. Friis, "The Norwegian Government-In-Exile, 1940–45" in Scandinavian Studies. Essays Presented to Dr. Henry Goddard Leach on the Occasion of his Eighty-fifth Birthday (1965), p422-444.

- ^ Dear and Foot, Oxford Companion (1995) pp 818–21

- ^ Johs Andenaes, Norway and the Second World War (1966)

- ^ John H. Woodruff, Relations between the Netherlands Government-in-Exile and occupied Holland during World War II (1964)

- ^ van Panhuys, HF (1978) International Law in the Netherlands, Volume 1, T.M.C. Asser Instituut P99

- ^ "World War II Timeline". Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- ^ Crampton, R. J. Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century — and after. Routledge. 1997.

- ^ Eliezer Yapou, Governments in Exile, 1939–1945: Leadership from London and Resistance at Home (1998) ch 4 online Archived 2018-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9780874136531. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Winston Churchill, Closing the Ring (vol. 5 of The Second World War) (1952) ch 26

- ^ Walter R. Roberts, Tito, Mihailović, and the Allies, 1941–1945 (1987).

- ^ Willian L Shirer, "Rise and Fall of the third Reich"

Further reading

- Bosworth, Richard, and Joseph Maiolo, eds. The Cambridge History of the Second World War: Volume 2, Politics and Ideology (Cambridge University Press, 2015) summary of Alliwed diplomacy on pp 301–323.

- Craig, Gordon A. "Diplomats and Diplomacy During the Second World War", in The Diplomats, 1939–1979 (Princeton University Press, 2019) pp. 11–37.

- Dear, Ian C. B. and Michael Foot, eds. The Oxford Companion to World War II (2005); encyclopedic coverage by experts. excerpt; also published as The Oxford Companion to the Second World War

- Overy, Richard J. The Origins of the Second World War (3rd ed. 2008)

- Overy, Richard J. Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War, 1931–1945 (2022), a standard one-volume history of all aspects of WWII excerpt

- Polmar, Norman and Thomas B. Allen. World War II: The Encyclopedia of the War Years, 1941–1945 (1996; reprints have slightly different titles.)

- Rothwell, Victor. War Aims in the Second World War: The War Aims of the Key Belligerents 1939–1945 (2006)

- Steiner, Zara. The Triumph of the Dark: European International History 1933–1939 (Oxford History of Modern Europe) (2011) 1248pp; comprehensive coverage of Europe heading to war excerpt and text search

- Watt, Donald Cameron. How War Came: The Immediate Origins of the Second World War 1938–1939 (1990) highly detailed coverage; online

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (1994) comprehensive coverage of the war with emphasis on diplomacy excerpt and text search also complete text online

- Wheeler-Bennett, John. The Semblance Of Peace: The Political Settlement After The Second World War (1972) thorough diplomatic coverage 1939–1952

- Woodward, Llewelyn. "The Diplomatic History of the Second World War" in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898–1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online free pp 798–818.

The Allies

- Barker, Elisabeth. Churchill & Eden at War (1979) 346p

- Beitzell, Robert. The uneasy alliance; America, Britain, and Russia, 1941–1943 (1972) online

- Beschloss, Michael. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman, and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945 (2002). online

- Burns, James. Roosevelt: the Soldier of Freedom (1970). online

- Butler, Susan. Roosevelt and Stalin: Portrait of a Partnership (2015) online

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War (6 vol 1948)

- Charmley, John. Churchill's Grand Alliance: The Anglo-American Special Relationship 1940–57 (1996)

- Dallek, Robert. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945 (1995). online

- Dutton, David. Anthony Eden: A Life and Reputation (1997) Online free

- Feis, Herbert. Churchill Roosevelt Stalin: The War They Waged and the Peace They Sought: A Diplomatic History of World War II (1957), online by a senior official of the U.S. State Department

- Feis, Herbert. China Tangle: American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission (1953) online

- Fenby, Jonathan. Alliance: The Inside Story of How Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill Won One War and Began Another (2015) excerpt

- Fenby, Jonathan. Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost (2005). online

- Gibson, Robert. Best of Enemies (2nd ed. 2011). Britain and France

- Glantz, Mary E. FDR and the Soviet Union: The President's Battles over Foreign Policy (2005)

- Langer, William and S. Everett Gleason. The Challenge to Isolation, 1937–1940 (1952); and The Undeclared War, 1940–1941 (1953) highly influential, wide-ranging two-volume semi-official American diplomatic history online

- Louis, William Roger; Imperialism at Bay: The United States and the Decolonization of the British Empire, 1941–1945 (1978)

- McNeill, William Hardy. America, Britain, & Russia: Their Co-Operation and Conflict, 1941–1946 (1953), 820pp; comprehensive overview

- May, Ernest R. Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France (2000).

- Nasaw, David. The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy (2012), US ambassador to Britain, 1937–40; pp 281–486

- Rasor, Eugene L. Winston S. Churchill, 1874–1965: A Comprehensive Historiography and Annotated Bibliography (2000) 712 pp.

- Reynolds, David. "The diplomacy of the Grand Alliance" in The Cambridge History of the Second World War: vol. 2 (2015) pp 276–300,

- Reynolds, David, ed. Allies at War: the Soviet, American and British Experience 1939–1945 (1994)

- Reynolds, David. From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the International History of the 1940s (2007)

- Roberts, Geoffrey. Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953 (2006).

- Sainsbury, Keith. Turning Point: Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill & Chiang-Kai-Shek, 1943: The Moscow, Cairo & Teheran Conferences (1985) 373pp online

- Smith, Bradley F. The War's Long Shadow: The Second World War and Its Aftermath: China, Russia, Britain, America (1986) online

- Smith, Gaddis. American Diplomacy During the Second World War, 1941–1945 (1965) online

- Taylor, Jay. The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China (2009).

- de Ven, Hans van, Diana Lary, Stephen MacKinnon, eds. Negotiating China's Destiny in World War II (Stanford University Press, 2014) 336 pp. online review

- Woods, Randall Bennett. Changing of the Guard: Anglo-American Relations, 1941–1946 (1990)

- Woodward, Llewellyn. British Foreign Policy in the Second World War (1962); online free; this is a summary of his 5-volume highly detailed history--online 5 volumes

Primary sources

- Maisky, Ivan. The Maisky Diaries: The Wartime Revelations of Stalin's Ambassador in London edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky, (Yale UP, 2016); highly revealing commentary 1934–43; excerpts; abridged from 3 volume Yale edition; online review

- Reynolds, David, and Vladimir Pechatnov, eds. The Kremlin Letters: Stalin's Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (2019)

- Stalin's Correspondence With Churchill Attlee Roosevelt and Truman 1941–45 (1958)

Governments in exile

- Auty, Phyllis and Richard Clogg, eds. British Policy towards Wartime Resistance in Yugoslavia and Greece (1975).

- Engel, David (2014). In the Shadow of Auschwitz: The Polish Government-in-exile and the Jews, 1939–1942. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469619576.

- Glees, Anthony. Exile Politics During the Second World War (1982)

- Lanicek, Jan, et al. Governments-in-Exile and the Jews during the Second World War (2013) excerpt and text search

- McGilvray, Evan. A Military Government in Exile: The Polish Government in Exile 1939–1945, A Study of Discontent (2012)

- Pabico, Rufino C. The Exiled Government: The Philippine Commonwealth in the United States During the Second World War (2006)

- Tendyra, Bernadeta. The Polish Government in Exile, 1939–45 (2013)

- Toynbee, Arnold, ed. Survey Of International Affairs: Hitler's Europe 1939–1946 (1954) online

- Yapou, Eliezer. Governments in Exile, 1939–1945: Leadership from London and Resistance at Home (2004) online, comprehensive coverage

Axis

- Bix, Herbert P. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (2001) excerpt and text search

- DiNardo, Richard L. "The dysfunctional coalition: The Axis Powers and the Eastern Front in World War II", The Journal of Military History (1996) 60#4 pp 711–730

- DiNardo, Richard L. Germany and the Axis Powers: From Coalition to Collapse (2005) excerpt and text search

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich at War (2010), a comprehensive history excerpt and text search

- Feis, Herbert. The Road to Pearl Harbor: The Coming of the War Between the United States and Japan (1950). classic history by senior American official. online

- Gigliotti, Simone. and Hilary Earl, eds. A Companion to the Holocaust (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

- Gilbert, Martin. The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust (3rd ed. 2004). online

- Gilbert, Martin. The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War (1985) online

- Goda, Norman J. W. "The diplomacy of the Axis, 1940–1945" in The Cambridge History of The Second World War: vol. 2 (2015) pp 275– 300.

- Kertesz, Stephen D. Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary Between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia (U of Notre Dame Press, 1953).

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: 1936–1945 Nemesis (2001), 1168pp; excerpt and text search

- Knox, MacGregor. Hitler's Italian Allies: Royal Armed Forces, Fascist Regime, and the War of 1940–1943 (2000) online

- Leitz, Christian. Nazi Foreign Policy, 1933–1941: The Road to Global War (2004) 201pp

- Mallett, Robert. Mussolini and the Origins of the Second World War, 1933–1940 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Martin, Bernd. Japan and Germany in the Modern World (1995)

- Mazower, Mark. Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe (2009) excerpt and text search

- Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44 (2001).

- Nekrich, Aleksandr Moiseevich. Pariahs, Partners, Predators: German-Soviet relations, 1922–1941 (Columbia University Press, 1997).

- Noakes, Jeremy and Geoffrey Pridham, eds. Nazism 1919–1945, vol. 3: Foreign Policy, War and Racial Extermination (1991), primary sources

- Sipos, Péter et al. "The Policy of the United States towards Hungary during the Second World War" Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum (1983) 29#1 pp 79–110 online.

- Thorne, Christopher G. The Issue of War: States, Societies, and the Coming of the Far Eastern Conflict of 1941–1945 (1985) sophisticated analysis of each major power facing Japan

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (2008), 848pp excerpt and text search

- Toynbee, Arnold, ed. Survey Of International Affairs: Hitler's Europe 1939–1946 (1954) online; 760pp; Highly detailed coverage of Germany, Italy and conquered territories.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933–1939: The Road to World War II (2005)

- Wright, Jonathan. Germany and the Origins of the Second World War (2007) 223pp

Espionage

- Andrew, Christopher M. Defend the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009).

- Breuer, William B. The Secret War with Germany: Deception, Espionage, and Dirty Tricks, 1939–1945 (Presidio Press, 1988).

- Crowdy, Terry. Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II (Osprey, 2008).

- De Jong, Louis. The German Fifth Column in the Second World War (1953) covers activities in all major countries. online

- Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's ULTRA: Codebreaking and the War against Japan, 1942–1945 (1992).

- Haufler, Hervie. Codebreakers' Victory: How the Allied Cryptographers Won World War II (2014).

- Hinsley, F. H., et al. British Intelligence in the Second World War (6 vol. 1979).

- Jörgensen, Christer. Spying for the Fuhrer: Hitler's Espionage Machine (2014).