Listeria

| Listeria | |

|---|---|

| |

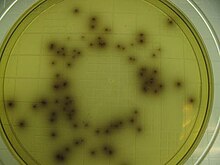

| micrograph of Listeria monocytogenes bacterium in tissue | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Bacillales |

| Family: | Listeriaceae |

| Genus: | Listeria Pirie 1940 |

| Species | |

|

L. aquatica | |

Listeria is a

in others who have been severely infected.Listeriosis is a serious disease for humans; the overt form of the disease has a

Background

In the late 1920s, two groups of researchers independently identified L. monocytogenes from animal outbreaks, naming it Bacterium monocytogenes.

The genus Listeria as of 2024[update] is known to contain 28 species, classified into two groups: sensu stricto and sensu lato.[13][3] Listeria sensu strictu contains L. monocytogenes alongside nine other closely related species: L. cossartiae,[14] L. farberi, L. immobilis,[14] L. innocua, L. ivanovii,[15] L. marthii,[16] L. seeligeri, L. swaminathanii[17] and L. welshimeri. Listeria sensu lato contains the remaining 18 species: L. aquatica,[18] L. booriae,[19] L. cornellensis,[18] L. costaricensis,[20] L. fleischmannii,[21] L. floridensis,[18] L. goaensis,[22] L. grandensis,[18] L. grayi, L. ilorinensis,[23] L. newyorkensis,[19] L. portnoyi,[14] L. riparia,[18] L. rocourtiae,[24] L. rustica,[14] L. thailandensis,[25] L. valentina[26] and L. weihenstephanensis.[27] Listeria dinitrificans, previously thought to be part of the genus Listeria, was reclassified into the new genus Jonesia.[28]

All species within the genus Listeria are

Listeria can be found in soil, which can lead to vegetable contamination. Animals can be carriers. Listeria has been found in uncooked meats, uncooked vegetables, fruits including

Pathogenesis

Listeria uses the cellular machinery to move around inside the host cell. It induces directed polymerization of actin by the ActA transmembrane protein, thus pushing the bacterial cell around.[35]

Listeria monocytogenes, for example, encodes virulence genes that are

The majority of Listeria bacteria are attacked by the immune system before they are able to cause infection. Those that escape the immune system's initial response, however, spread through intracellular mechanisms, which protects them from circulating immune factors (AMI).[33]

To invade, Listeria induces macrophage phagocytic uptake by displaying D-galactose in their teichoic acids that are then bound by the macrophage's polysaccharides. Other important adhesins are the internalins.[34] Listeria uses internalin A and B to bind to cellular receptors. Internalin A binds to E-cadherin, while internalin B binds to the cell's Met receptors. If both of these receptors have a high enough affinity to Listeria's internalin A and B, then it will be able to invade the cell via an indirect zipper mechanism.[citation needed] Once phagocytosed, the bacterium is encapsulated by the host cell's acidic phagolysosome organelle.[32] Listeria, however, escapes the phagolysosome by lysing the vacuole's entire membrane with secreted hemolysin,[36] now characterized as the exotoxin listeriolysin O.[32] The bacteria then replicate inside the host cell's cytoplasm.[33]

Listeria must then navigate to the cell's periphery to spread the infection to other cells. Outside the body, Listeria has

Epidemiology

The

Prevention

Preventing listeriosis as a

Keeping foods in the home refrigerated below 4 °C (39 °F) discourages bacterial growth. Unpasteurized dairy products may pose a risk.[54] Cooking all meats (including beef, pork, poultry, and seafood) to a safe internal temperature, typically 73 °C (165 °F), will kill the food-borne pathogen.[55]

Treatment

Non-invasive listeriosis: bacteria are retained within the digestive tract. Symptoms are mild, lasting only a few days and requiring only supportive care. Muscle pain and fever can be treated with over-the-counter pain relievers; diarrhea and gastroenteritis can be treated with over-the-counter medications.[55]

Invasive listeriosis: bacteria have spread to the bloodstream and central nervous system. Treatment includes intravenous delivery of high-dose

In cases of pregnancy, prompt treatment is critical to prevent bacteria from infecting the

Asymptomatic patients who have been exposed to Listeria typically are not treated, but are informed of the signs and symptoms of the disease and advised to return for treatment if any develop.[55]

Research

Some Listeria species are opportunistic pathogens: L. monocytogenes is most prevalent in the elderly, pregnant mothers, and patients infected with HIV. With improved healthcare leading to a growing elderly population and extended life expectancies for HIV infected patients, physicians are more likely to encounter this otherwise-rare infection (only seven per 1,000,000 healthy people are infected with virulent Listeria each year).[32] Better understanding the cell biology of Listeria infections, including relevant virulence factors, may lead to better treatments for listeriosis and other intracytoplasmic parasite infections.

In oncology, researchers are investigating the use of Listeria as a cancer vaccine, taking advantage of its "ability to induce potent innate and adaptive immunity" by activating gamma delta T cells. [37][59]

See also

- 2008 Canada listeriosis outbreak

- 2011 United States listeriosis outbreak

- 2017–2018 South African listeriosis outbreak

- 2018 Australian rockmelon listeriosis outbreak

- List of foodborne illness outbreaks

References

- ^ Jones, D. 1992. Current classification of the genus Listeria. In: Listeria 1992. Abstracts of ISOPOL XI, Copenhagen, Denmark). p. 7-8. ocourt, J., P. Boerlin, F.Grimont, C. Jacquet, and J-C. Piffaretti. 1992. Assignment of Listeria grayi and Listeria murrayi to a single species, Listeria grayi, with a revised description of Listeria grayi. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:171-174.

- ^ Boerlin et al. 1992. L. ivanovii subsp. londoniensis subsp. novi. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:69-73. Jones, D., and H.P.R. Seeliger. 1986. International committee on systematic bacteriology. Subcommittee the taxonomy of Listeria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 36:117-118.

- ^ PMID 38126771.

- ISBN 0-471-98880-4.

- ^ Christelle Guillet, Olivier Join-Lambert, Alban Le Monnier, Alexandre Leclercq, Frédéric Mechaï, Marie-France Mamzer-Bruneel, Magdalena K. Bielecka, Mariela Scortti, Olivier Disson, Patrick Berche, José Vazquez-Boland, Olivier Lortholary, and Marc Lecuit. "Human Listeriosis Caused by Listeria ivanovii". Emerg Infect Dis. 2010 January; 16(1): 136–138.

- ^ "Listeria". FoodSafety.gov. 12 April 2019.

- ISSN 0368-3494.

- ISSN 0368-3494.

- PMID 1713054.

- ^ Elliot T. Ryser, Elmer H. Marth. Listeria, Listeriosis, and Food Safety. Second edition. Elmer Marth. 1999.

- ISSN 0378-1097.

- ^ Nyfeldt, A (1929). "Etiologie de la mononucleose infectieuse". Comptes Rendus des Séances de la Société de Biologie. 101: 590–591.

- PMID 27129530.

- ^ PMID 33999788.

- ISSN 1466-5034.

- PMID 19667380.

- PMID 35658601.

- ^ PMID 24599893.

- ^ PMID 25342111.

- PMID 29458479.

- PMID 22523164.

- PMID 30156532.

- PMID 35731854.

- PMID 19915117.

- PMID 30457511.

- PMID 33016862.

- PMID 22544790.

- ISSN 0020-7713.

- ^ "Listeria outbreak expected to cause more deaths across US in coming weeks". The Guardian. London. 29 September 2011.

- ^ Times, Los Angeles (16 January 2015). "California plant issues massive apple recall due to listeria". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Controlling Listeria Contamination in Your Meat Processing Plant". Government of Ontario. 27 February 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Southwick, F. S.; D. L. Purich. "More About Listeria". University of Florida Medical School. Archived from the original on 22 February 2001. Retrieved 7 March 2007. [No longer accessible. Archived version available here.]

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology". Listeria monocytogenes and Listeriosis. Kenneth Todar University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Biology. 2003. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- ^ a b "Statistics about Salmonella food poisoning". WrongDiagnosis.com. 27 February 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- PMID 9234509.

- ^ PMID 2507553.

- ^ a b "Listeria". MicrobeWiki.Kenyon.edu. 16 August 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- ^ PMID 9673261.

- S2CID 39441473.

- ^ "Granny Smith, Gala apples recalled due to listeria". abc7news.com. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Center for Science in the Public Interest – Nutrition Action Healthletter – Food Safety Guide – Meet the Bugs Archived 18 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b William Neuman (27 September 2011). "Deaths From Cantaloupe Listeria Rise". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Claughton, David; Kontominas, Bellinda; Logan, Tyne (14 March 2018). "Rockmelon listeria: Rombola Family Farms named as source of outbreak". ABC News Australia. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018.

- ^ Australian Associated Press (3 March 2018). "Third death confirmed in Australia's rockmelon listeria outbreak". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Australian Associated Press (16 March 2018). "Fifth person dies as a result of rockmelon listeria outbreak". SBS News. Special Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Josephine Tovey (16 November 2011). "$236,000 fine for foul flight chicken". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Warning: Prepackaged Caramel Apples Linked To 5 Deaths". Yahoo Health. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "Listeria outbreak from caramel apples has killed four". USA TODAY. 20 December 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Listeria outbreak: Toll rises to six as Sussex patient dies 1 August 2019 bbc.co.uk accessed 2 August 2019

- ^ "Two more deaths brings death toll up to five". BBC News. 14 June 2019.

- ^ "'Smoked salmon' listeria kills two in Australia". 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Three deaths, miscarriage tied to meat supplier in listeria cases". NL Times. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ "Maple Leaf Foods assessing Listeria-killing chemical". ctv.ca. ctvglobemedia. The Canadian Press. 12 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ "Food Safety - Listeria". Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d "CDC - Listeria - Home". cdc.gov/listeria. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ S2CID 11352292.

- ^ "Listeria infection (listeriosis): symptoms and causes". mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- PMID 19173022.

- ^ Greenemeier L (21 May 2008). "Recruiting a Dangerous Foe to Fight Cancer and HIV". Scientific American.

Further reading

- Abrishami S. H.; Tall B. D.; Bruursema T. J.; Epstein P. S.; Shah D. B. (1994). "Bacterial adherence and viability on cutting board surfaces". .

- Zhifa Liu; Changhe Yuan; Stephen B. Pruett (2012). "Machine learning analysis of the relationship between changes in immunological parameters and changes in resistance to Listeria monocytogenes: a new approach for risk assessment and systems immunology". Toxicol. Sci. 129 (1): 1:57–73. PMID 22696237.

- Allerberger F (2003). "Listeria: growth, phenotypic differentiation and molecular microbiology". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 35 (3): 183–189. PMID 12648835.

- Bayles D. O.; Wilkinson B. J. (2000). "Osmoprotectants and cryoprotectants for Listeria monocytogenes". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 30 (1): 23–27. S2CID 29706638.

- Bredholt S.; Maukonen J.; Kujanpaa K.; Alanko T.; Olofson U.; Husmark U.; Sjoberg A. M.; Wirtanen G. (1999). "Microbial methods for assessment of cleaning and disinfection of food-processing surfaces cleaned in a low-pressure system". European Food Research and Technology. 209 (2): 145–152. S2CID 96177510.

- Chae M. S.; Schraft H. (2000). "Comparative evaluation of adhesion and biofilm formation of different Listeria monocytogenes strains". PMID 11139010.

- Chen Y. H.; Jackson K. M.; Chea F. P.; Schaffner D. W. (2001). "Quantification and variability analysis of bacterial cross-contamination rates in common food service tasks". Journal of Food Protection. 64 (1): 72–80. PMID 11198444.

- Davidson C. A.; Griffith C. J.; Peters A. C.; Fieding L. M. (1999). "Evaluation of two methods for monitoring surface cleanliness ñ ATP bioluminescence and traditional hygiene swabbing". Luminescence. 14 (1): 33–38. PMID 10398558.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2005. "Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook: The ìBad Bug Book" Food and Drug Administration, College Park, MD. Accessed: 1 March 2006.

- Foschino R.; Picozzi C.; Civardi A.; Bandini M.; Faroldi P. (2003). "Comparison of surface sampling methods and cleanability assessment of stainless steel surfaces subjected or not to shot peening". .

- Frank, J. F. 2001. "Microbial attachment to food and food contact surfaces". In: Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Vol. 43. ed. Taylor, S. L. San Diego, CA. Academic Press., Inc. 320–370.

- Gasanov U.; Hughes D.; Hansbro P. M. (2005). "Methods for the isolation and identification of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes: a review". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 29 (5): 851–875. PMID 16219509.

- Gombas D. E.; Chen Y.; Clavero R. S.; Scott V. N. (2003). "Survey of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods". Journal of Food Protection. 66 (4): 559–569. PMID 12696677.

- Helke D. M.; Somers E. B.; Wong A. C. L. (1993). "Attachment of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella typhimurium to stainless steel and Buna-N-rubber surfaces in the presence of milk and individual milk components". Journal of Food Protection. 56 (6): 479–484. PMID 31084181.

- Kalmokoff M. L.; Austin J. W.; Wan X. D.; Sanders G.; Banerjee S.; Farber J. M. (2001). "Adsorption, attachment and biofilm formation among isolates of Listeria monocytogenes using model condit ions". PMID 11576310.

- Kusumaningrum H. D.; Riboldi G.; Hazeleger W. C.; Beumer R. R. (2003). "Survival of foodborne pathogens on stainless steel surfaces and cross-contamination to foods". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 85 (3): 227–236. PMID 12878381.

- Lin C.; Takeuchi K.; Zhang L.; Dohm C. B.; Meyer J. D.; Hall P. A.; Doyle M. P. (2006). "Cross-contamination between processing equipment and deli meats by Listeria monocytogenes". Journal of Food Protection. 69 (1): 559–569. PMID 16416903.

- Low J. C.; Donachie W. (1997). "A review of Listeria monocytogenes and listeriosis". PMID 9125353.

- Nikolova, M., Todorova, T. T., Tsankova, G., & Ermenlieva, N. (2016). А possible case of а newborn premature baby with Listeria monocytogenes infection. Scripta Scientifica Medica, 48(2).

- MacNeill S.; Walters D. M.; Dey A.; Glaros A. G.; Cobb C. M. (1998). "Sonic and mechanical toothbrushes". PMID 9869348.

- Maxcy R. B. (1975). "Fate of bacteria exposed to washing and drying on stainless steel". Journal of Milk and Food Technology. 38 (4): 192–194. .

- McInnes C.; Engel D.; Martin R. W. (1993). "Fimbriae damage and removal of adherent bacteria after exposure to acoustic energy". Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 8 (5): 277–282. PMID 7903443.

- McLauchlin J. (1996). "The relationship between Listeria and listeriosis". Food Control. 7 (45): 187–193. .

- Montville R.; Chen Y. H.; Schaffner D. W. (2001). "Glove barriers to bacterial cross contamination between hands to food". Journal of Food Protection. 64 (6): 845–849. PMID 11403136.

- Moore G.; Griffith C.; Fielding L. (2001). "A comparison of traditional and recently developed methods for monitoring surface hygiene within the food industry: a laboratory study". Dairy, Food, and Environmental Sanitation. 21: 478–488.

- Moore G.; Griffith C. (2002a). "Factors influencing recovery of microorganisms from surfaces by use of traditional hygiene swabbing". Dairy, Food, and Environmental Sanitation. 22: 410–421.

- Parini M. R.; Pitt W. G. (2005). "Removal of oral biofilms by bubbles". PMID 16383051.

- Pfaff, N. F., & Tillett, J. (2016). Listeriosis and Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy: Essentials for Healthcare Providers. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing, 30(2), 131.

- Rocourt J. (1996). "Risk factors for listeriosis". Food Control. 7 (4/5): 195–202. .

- Ross, H. (2015). Food Hygiene: Rare Burgers. Eur. Food & Feed L. Rev., 382.

- Salo S.; Laine A.; Alanko T.; Sjoberg A. M.; Wirtanen G. (2000). "Validation of the microbiological methods Hygicult dipsilde, contact plate, and swabbing in surface hygiene control: a Nordic collaborative study". Journal of AOAC International. 83 (6): 1357–1365. PMID 11128138.

- Schlech W. F. (1996). "Overview of listeriosis". Food Control. 7 (4/5): 183–186. .

- Seymour I. J.; Burfoot D.; Smith R. L.; Cox L. A.; Lockwood A. (2002). "Ultrasound decontamination of minimally processed fruits and vegetables". International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 37 (5): 547–557. .

- Stanford C. M.; Srikantha R.; Wu C. D. (1997). "Efficacy of the Sonicare toothbrush fluid dynamic action on removal of supragingival plaque". Journal of Clinical Dentistry. 8 (1): 10–14.

- USDA-FSIS. (United States Department of Agriculture – Food Safety and Inspection Service) 2003. "FSIS Rule Designed To Reduce Listeria monocytogenes In Ready-To-Eat Meat And Poultry Products" Archived 28 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service, Washington, DC. Accessed: 1 March 2006

- Vorst K. L.; Todd E. C. D.; Ryser E. T. (2004). "Improved quantitative recovery of Listeria monocytogenes from stainless steel surfaces using a one-ply composite tissue". Journal of Food Protection. 67 (10): 2212–2217. PMID 15508632.

- Whyte W.; Carson W.; Hambraeus A. (1989). "Methods for calculating the efficiency of bacterial surface sampling techniques". Journal of Hospital Infection. 13 (1): 33–41. PMID 2564016.

- Wu-Yuan C. D.; Anderson R. D. (1994). "Ability of the SonicareÆ electronic toothbrush to generate dynamic fluid activity that removes bacteria". The Journal of Clinical Dentistry. 5 (3): 89–93.

- Zhao P.; Zhao T.; Doyle M. P.; Rubino J. R.; Meng J. (1998). "Development of a model for evaluation of microbial cross-contamination in the kitchen". Journal of Food Protection. 61 (8): 960–963. PMID 9713754.

- Zottola E. A., Sasahara K. C.; Sasahara (1994). "Microbial biofilms in the food processing industry ñ should they be a concern?". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 23 (2): 125–148. PMID 7848776.

External links

- Listeriosis at Curlie

- Listeria genomes and related data at PATRIC, funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- Listeria at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase