Classical Anatolia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Classical Anatolia is

The

Anatolia came under Roman rule entirely following the Mithridatic Wars of 88–63 BC. Roman control of Anatolia was strengthened by a 'hands off' approach by Rome, allowing local control to govern effectively and providing military protection. In the early 4th century, Constantine the Great established a new administrative centre at Constantinople, and by the end of the 4th century a new eastern empire was established with Constantinople as its capital, referred to by historians as the Byzantine Empire from the original name, Byzantium.

In the subsequent centuries up to including the advent of the

Early antiquity

- "On the refusal of Alyattes to give up his supplicants when Cyaxares sent to demand them of him, war broke out between the Lydians and the Medes, and continued for five years, with various success. In the course of it the Medes gained many victories over the Lydians, and the Lydians also gained many victories over the Medes."

Alyattes issued minted electrum coins, and his successor Croesus, ruling c. 560–546 BC, became known for being the first to issue gold coins.

The southeast of Anatolia was ruled by the

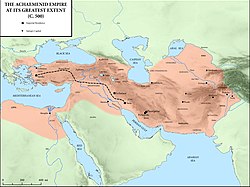

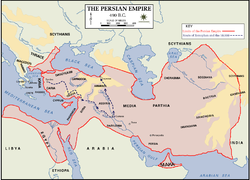

Persian rule

The Medean Empire turned out to be short lived (c. 625 – 549 BC). By 550 BC, the

The Persians, who had scant resources for governing their vast empire, ruled relatively benignly as conquerors, attempting to obtain the cooperation of the local elite in governance. They ruled their vassal states by appointing local rulers, or

Anatolia was carved up under Persian

Within the hierarchical system, Sparda was a Great Satrapy consisting of the Major Satrapies of Sarda (including minor satrapies of Hellespontine Phrygia, Greater Phrygia, Caria, and Thracia) and Cappadocia. Note that Ionia and Aeolis were not considered separate entities by the Persians, while Lycia was included in semi-autonomous Caria, and Sparda included the offshore islands. Greater Phrygia included Lycaonia, Pisidia, and Pamphylia. Cappadocia initially included Cilicia, also known as Cappadocia-beside-the-Taurus, and Paphlagonia.

Assyria was a Main Satrapy of the Great Satrapy of Babylon, and included Cilicia, while Armenia was a Main Satrapy within the Great Satrapy of Media.[3]

Anatolia remained one of the most principal regions of the empire during its entire existence. During the reign of Darius the Great, the Royal Road, which directly linked the city of Susa with the western Anatolian city of Sardis.

The fall of Lydia (546 BC) and the Lydian revolt

By 550 BC Lydia controlled the Greek coastal cities, who paid tribute, and most of Anatolia, except Lycia, Cilicia and Cappadocia. In 547 BC, King Croesus, who had amassed great wealth and military power, but concerned by the growing Persian power and obvious intent, took advantage of the instability of the Persian revolt and besieged and captured the Persian city of Pteria in Cappadocia.[1][2]

Lydia then became the Persian

Mazares was followed by Harpagus (544–530 BC) on his death, and then Oroetus (530–520 BC). Oroetus became the first satrap recorded as demonstrating insubordination with respect to the central power of Persia. When Cambyses (530–522 BC), who succeeded his father Cyrus, died, the Persian Empire was in chaos prior to Darius the Great (522–486 BC) finally securing control. Oroetus defied Darius' orders to assist him, whereupon Bagaeus (520–517 BC) was sent by Darius to arrange his murder.

The subjugation of Ionia and the Ionian Revolt (500–493 BC)

Cyrus had initially unsuccessfully tried to persuade the Aeolian and Ionian cities to rebel against Lydia. At the time of the fall of Sardis, only one city, Miletus, had made terms with Cyrus. According to Herodotus, when Lydia fell to Cyrus, the Greek cities begged him to allow them to exist within the former Lydian territories on similar terms to those they had earlier enjoyed, Cyrus pointed out that they were too late, and they started building defensive structures. They appealed to Sparta for help, but Sparta refused, instead warning Cyrus not to threaten the Greeks. Cyrus was unimpressed, but nevertheless headed east without bothering them further. This account seems somewhat conjectural.[2][5]

Following the defeat of the Lydian revolt, Mazares began to reduce the other cities in the Lydian lands one by one, starting with Priene and Magnesia. However, Mazares died, and was replaced by another Mede, Harpagus (544–530 BC), who completed the subduing of Asia Minor. Some communities, rather than face a siege, chose exile, including Phocaea to Corsica and Teos to Abdera in Thrace. Although our principal source for this period, Herodotus of Halicarnassus, implies this was a swift process, it is more likely that it took four years to subdue the region completely, and the Ionian colonies on the coastal islands remained largely untouched.[2][4]

According to

However, Herodotus, as is so often our only source, had an agenda in his imprecise accounts, which do not fit well with what is known of the period. It is likely that the affair in Naxos represented a democratic revolt against the tyrants.[2]

Other satrapies

Hellespontine Phrygia

Greater Phrygia

Greater Phrygia was a minor satrapy of Sparda, with its capital at Celaenae. It concluded Lycaonia, Pisidia, and Pamphylia.

Semi-autonomous jurisdictions

Cilicia

Cilicia remained a semi-independent minor satrapy under both Croesus of Lydia, and under Persian rule, although paying tribute. Similarly Lycia remained under petty local dynasts, with allegiance to Persia.

Mysia

Mysia was ruled by its own dynasty within the minor satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia.

Caria

Greco-Persian Wars 499–449 BC

The preceding events of the

From the Greek perspective the first war was when Darius assembled a fleet in

Greece was spared further invasions when an unplanned interbellum (490–480 BC) occurred due to an insurrection in

Following these Persian reverses, the Greek cities of Asia Minor again rebelled. The focus of the war now moved to the Aegean islands with the formation of the

Skirmishes continued, and the Greek cities of Asia Minor continued to be pawns in the struggles.

Final years: the invasion of the Macedonians 358–330 BC

The later years of the Empire were beset by internal turmoil.

Advancing on

On reaching

Darius himself was murdered in 330 BC, and shortly afterwards Alexander routed the remaining Persian forces at the Battle of the Persian Gate and the Achaemenid Empire was over.

Hellenistic period

Alexander the Great

Administratively he continued the

Wars of the Diadochi and division of Alexander's empire

In June 323 BC,

Power often lay with the Satraps, usually generals. In Anatolia, this initial division of power at Babylon was as follows;

Western Anatolia: Hellespontine Phrygia by Leonnatus, Lydia by Menander, Caria by Asander

Central Anatolia: Phrygia, Lycia and Pamphylia by Antigonus, Cappadocia and Paphlagonia by Eumenes of Cardia, Cilicia by Philotas

Eastern Anatolia: Armenia by Neoptolemus

However, dissent was endemic, and almost continuous war ensued amongst the Macedonian generals, lasting over 40 years; these wars were referred to as the

The second partitioning did little to quell the continuing scheming and jockeying for power. Antipater's illness in 320 BC led him to appoint Polyperchon as regent, passing over his own son Cassander, who now conspired with Antigonus. The result was civil war (Second War of the Diadochi) with Cassander declaring himself regent in 317 BC and King in 305 BC, having had Alexander IV murdered in 309 BC.

Meanwhile, Antigonus in Phrygia was expanding east forcing

In post-Ipsus Anatolia, Lysimachus held the west and north, Seleucus the east, and Ptolemy the south east. For a while Pleistarchus, Antipater's son and Cassander's brother ruled Cilicia, before being driven out the following year (300 BC) by Demetrius. The other exception was Pontus which under Mithridates I managed to gain independence.

The third partition of 301 BC was no more effective at bringing stability to the region than its predecessors. Demetrius, who eventually became King of Macedon (294 BC – 288 BC), was still at large controlling a significant naval force, raiding Lysimachus' territory in Asia Minor. Nor did the Ipsus alliance between the three kings last.

Lysimachian Empire 301–281 BC

Of the three empires carved out of Alexander's possessions following the battle of Ipsus, the Lysimachian of Thrace, Western (including Lydia, Ionia, Phrygia) and Northern Asia Minor, was the shortest lived. Lysimachus attempted unsuccessfully to extend his possessions in Europe and Greece. Some of Lysimachus' cruelty, such as the murder of his son Agathocles in 284 BC engendered both revulsion and revolt. Distrusting Seleucus, Lysimachus had now allied himself with Ptolemy. Seleucus invaded the Lysimachian lands and in the ensuing Battle of Corupedium, near Sardis in 281 BC, Lysimachus was killed and Seleucus seized control over western Asia Minor.[11][13]

Ptolemaic Empire 301–30 BC

Of all the major satraps appointed on the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC),

Thereafter the Ptolemaic powers declined.

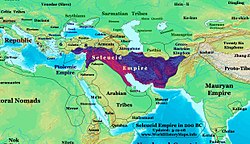

Seleucid Empire 301–64 BC

On the death of

After the death of Seleucus, the vast and unwieldy empire he left faced many trials, both from internal and external forces. His son

Antiochus I Soter was succeeded by his son

Seleucus II oversaw the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC) with Berenice's brother, Ptolemy III Euergetes. In Asia Minor a rebellion by his younger brother Antiochus Hierax led to Seleucus II leaving the lands beyond the Taurus Mountains to him following a defeat at Ancyra in 236 BC, although the latter was eventually driven out of Anatolia by Pergamon in 227 BC.[15] Seleucus' sister Laodice married Mithridates II in 245 BC and brought with her the lands of Phrygia as a dowry.[16] Despite this Mithridates joined Antiochus Hierax against Seleucus.

After the brief reign of Seleucus II's son

While the Seleucids continued to maintain lands in south eastern Anatolia the empire was progressively weakened on all fronts, and became progressively unstable, torn by civil war in the 2nd century BC. After the death of

Independent, semi-independent and client states

Pontus 291–63 BC

The

Pontus was founded by

His grandson,

Mithridates II's grandson,

Mithridates IV was succeeded by his nephew, Mithridates V (c. 150 – 120 BC), son of Pharnaces I. He assisted the Romans in suppressing the revolt by the pretender of Pergamon, Eumenes III. In exchange he received Phrygia from the Romans. He allied himself with Cappadocia by marrying his daughter Laodice to Ariarathes VI of Cappadocia.

His son,

Mithridatic wars 88–63 BC

He next turned his attention to Anatolia where he sought to partition Paphlagonia and Galatia with King Nicomedes III of Bithynia (127 – 94 BC) in 108 BC also acquiring Galatia and Armenia Minor but soon fell out with him over control of Cappadocia and by extension his ally Rome setting the scene for the subsequent series of Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC). Relations between the adjacent states of Pontus, Bithynia, Cappadocia and Armenia were complex. Mithridates' sister, Laodice was queen of Cappadocia, being married to Ariarathes VI (130 – 116 BC). Mithridates had his brother in law Ariarathes murdered, whereupon Laodice married Nicomedes III of Bithynia. Pontus and Bithynia then went to war over Cappadocia, and Mithridates had his nephew and new king, Ariarathes VII (116 – 101 BC) killed. Ariarethes' brother Ariarathes VIII (101 – 96 BC) ruled for a brief period before being replaced by Mithridates with his own son Ariarathes IX (101 – 96 BC). The Roman Senate then had Ariarathes replaced by Ariobarzanes I (95 – c. 63 BC). Mithrodates then dragged his eastern neighbour Armenia into the fray, since Tigranes the Great (95–55 BC) was his son in law.

Nicomedes IV of Bithynia (94 – 74 BC) declared war on Pontus aided by Roman legions in 89 BC launching the First Mithridatic War (89–84 BC). During this period, Mithridates swept through Asia Minor occupying most of it except Cilicia by 88 BC, before Roman retaliation forced his retreat and abandonment of all the occupied territory. Mithridates still controlled his own Pontine lands and a second war by Rome (83–81 BC) was rather inconclusive and failed to dislodge him. In the meantime the Roman presence in Anatolia was steadily growing. As with Pergamon Nicomedes who had no heirs, bequeathed Bithynia to Rome. This provided the opportunity for Mithridates to invade Bithynia and precipitated the Third Mithridatic War (74–63 BC). Mithridates' position was considerably weakened following the fall of Armenia to Rome in 66 BC. Pompey had dislodged Mithridates from Pontus by 65 BC, who now retreated to his northern domains but was defeated by rebellion in his own family and died, possibly by suicide, ending the Pontine Kingdom as it then existed.

Aftermath

The lands were divided with the western part including the capital being absorbed into the Roman province of

Bithynia 326–74 BC

Bithynians were of Thracian origin. There is some evidence that even before the invasion of Alexander the Great, Bithynia enjoyed some independence.

Prusias II (156–154 BC) joined Pergamon in a war against Pharnaces I of Pontus (181–179 BC) but then attacked Pergamon (156–154 BC) with disastrous consequences. His son Nicomedes II (149 – 127 BC) sided with Rome in putting down the revolt by Eumenes III (133–129 BC), the pretender of Pergamon. His son Nicomedes III (127 – 94 BC) became entangled in the complex intermarriages of Pontus and Cappadocia, attempted to annex Paphlagonia and claim Cappadocia. He was succeeded by his son Nicomedes IV (94 – 74 BC) who bequeathed the kingdom to Rome, precipitating the Mithridatic Wars between Rome and Pontus who claimed Bithynia.

Galatia 276–64 BC

The Gauls retained traditional

In 64 BC Galatia became a client state of Rome and a Roman province in 25 BC following the reign of Amyntas (36–25 BC).[18]

Pergamon 281–133 BC

Attalus' son,

The last of the Attalid kings was Attalus III (138–133 BC), son of Eumenes II, who bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman Republic. However, a pretender, calling himself Eumenes III briefly seized the throne until captured by the Romans in 129 BC. The lands occupied by Pergamon were divided up between Cappadocia and Pontus while the rest came directly under Rome. Pergamon had acted as a client state to Rome after Apamea, but after the death of Attalus III became the Roman province of Asia (Asiana).[18]

Cappadocia 323–17 BC

At the time of the conquest by Alexander the Great, the Persian satrap was

Ariarathes III's son,

The Cappadocian monarchy then fell victim to the ambitions of

By this stage Cappadocia was effectively a Roman

Cilicia 323–67 BC

Cilicia had historically been ruled by the

Following the

In the 2nd century BC, Cilicia was notorious for the pirates based along the southern Tracheian coast. After the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes (138–129) the Seleucid Empire had become reduced to Syria and adjacent Cilicia. At one stage the Seleucid Empire was divided with Philip I (95–84 BC) ruling in Cilicia while his twin Antiochus IX ruled in Damascus.[24] With the rise of more independent states in Asia Minor, Cilicia came under the hegemony of various surrounding kingdoms, sometimes partitioned. during the Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC) between Rome and Pontus and their ally Armenia, Tigranes the Great of Armenia (95–55 BC) that state vastly expanded its borders at the expense of the Seleucids, and incorporated Cilicia c. 80 BC, until forced to retreat from the advancing Romans.[25]

Roman influence was being felt in Cilicia as early as 116 BC.[26] In 67 BC Pompey who had suppressed the pirates created the Roman province of

In the 1st century BC Cilicia was tied to Pontus.

Cilicia was a very diverse area, both geographically and demographically and parts of it remained difficult for any occupying power to subdue.[27] During this period, minor dynasts existed within Cilicia such as

Armenia 331–1 BC

Armenia in the 1st century BC formed a mountainous region in eastern Anatolia, bounded to the south by Syria and Mesopotamia and to the east by that part of

A satrapy under the Persians, it was largely ruled by the

However,

The period of greatest Armenian expansion occurred with

Minor kingdoms

Sophene and Commagene were among minor Anatolian states that at times were independent kingdoms and at others were annexed to surrounding territories. Both lay to the west of Armenia proper, adjoining Pontus, Cappadocia and Cilicia, from north to south.

Sophene

Sophene had been a province of ancient Armenia but became independent following the division of

Commagene

Commagene, a country on the west bank of the

Rhodes

The island of

Roman period

Roman Republic 190 – 27 BC

By 282 BC Rome had subdued northern Italy, and as a result of the

Part of Roman foreign policy was the declaration of foreign states as socius et amicus populi romani (ally and friend of the Roman people) by treaty agreements.

Roman intervention in Anatolia 3rd – 1st centuries BC

The rule of Rome in Anatolia was unlike any other part of their empire because of their light hand with regards to government and organization. Controlling unstable elements within the region was made simpler by the bequeathal of both Pergamon and Bithynia to the Romans by their kings.[31]

Punic (264–146 BC) and Macedonian (214–148 BC) wars

In the

Seleucid invasion of Europe and retreat from western Anatolia 196–188 BC

During the period just after Rome's victory, the

A stronger Pergamon suited Roman interests as a buffer state between the Aegean and the Seleucid Empire. However, Rome needed to intervene on a number of occasions to ensure the integrity of the enlarged territory, including wars against

Involvement with central Anatolian politics 190–17 BC

The interior of Anatolia had been relatively stable despite occasional incursions by the Galatians until the rise of the kingdoms of Cappadocia and Pontus in the 2nd century BC.

Bithynia, the other major kingdom in western Anatolia, had varying relations with Rome, and in particular its ally Pergamon. The last monarch, Nicomedes IV (94 – 74 BC) bequeathed his kingdom to Rome, precipitating the Mithridatic Wars between Rome when Pontus claimed Bithynia.[13]

Pontus and the Mithridatic Wars 89–63 BC

Rome, however, noticed once Mithridates turned his eye west in 108 BC, partitioning

By 91 BC Rome was again distracted by war, this time against

First war 89–84 BC

By now both Bithynia and Cappadocia were ruled by Roman protégés and were indebted to Rome who urged them to invade Pontus, a fatal miscalculation. Nicomedes invaded Pontus, Mithridates complained to Rome, boasted of his power and allies and unwisely hinted that Rome was vulnerable. The Roman Commissioners declared a state of war and the First Mithridatic War (89–84 BC) was launched.[34]

The war went well initially for the allies during 89–88 BC, since Rome was still involved in the Social War, taking Phrygia, Mysia, Bithynia, parts of the Aegean Ccoast, Paphlagonia, Caria, Lycea, Lycaonia and Pamphylia. Aquillius was defeated in the first direct engagement with the Romans, in Bithynia although the troops were actually raised locally. The other Roman commander was C. Cassius, governor of Asia, whose seat was at Pergamon, and as Mithridates overran the province, both fled from the mainland. Aquillius was handed back to Mithridates who executed him. Roman rule in Anatolia had been crushed, although a few areas of Asia Minor managed to hold out.

Although Sulla was then appointed to deal with Mithridates, events moved very slowly. However, worse was to come later in 88 BC. the '

Mithridates' problems were further complicated by a 'rogue' Roman army dispatched by Sulla's enemies in Rome, commanded by

Sulla set about re-organising the Roman administration in Western anatolia until 84 BC. Those cities that had resisted Mithridates were rewarded, for instance Rhodes regained the Peraea lost in the Macedonian wars. Those that had collaborated were forced to pay reparations. The combined effects of the war and aftermath were ruinous for the region and piracy abounded. Mithradates himself faced internal problems

Second war 83–81 BC

Given that many Romans thought that Mithridates had got off rather lightly following the first war, provocation was almost inevitable. Sulla left Ephesus in 84 BC to return to Rome and make war on his enemies, where he would eventually become dictator. He left Lucius Licinius Murena to govern the province of Asia. Murena proceeded to intervene in Cappadocia in 83 BC, where Mithrodates was also interfering with the recently restored Ariobarzanes I (95–63 BC). After two further raids with less justifiable pretexts, Mithridates retaliated, pursuing Murena and inflicting a number of defeats on Murena until Sulla (who had less territorial ambition than Murena) intervened and both antagonists withdrew to their former positions.

Murena had refused to recognise the treaty on a technicality and the

Third war 75–63 BC

When

By the time Lucullus arrived in 73 BC, Mithridates was anticipating him. Lucullus was assembling his legions in northern Phrygia, when Mithridates advanced rapidly through Paphlagonia into Bithynia, where he joined his naval forces and defeated the Roman fleet commanded by Cotta at the

Lucullus then resumed his original plan and advanced through Galatia and Paphlagonia to Pontus in 72 BC. By 71 BC he was through the Iris and Lycus valleys and into Pontus where he engaged Mithridates at Cabira. The result was disastrous for the Pontic forces, and Mithridates fled to Armenia. The Romans then set about subduing Pontus and Lesser Armenia while trying to persuade Mithridates, now the guest of Tigranes the Great to surrender. Tigranes spurned the Roman overtures and indicated he was prepared to fight, so Lucullus prepared to invade Armenia in 70 BC. In 69 he marched through Cappadocia to the Euphrates, crossing it at Tomisa and entering Sophene and the lands which Tigranes had recently acquired from the Seleucids and heading for the new imperial capital of Tigranocerta. There Tigranes found him besieging the city, and in the ensuing battle, was routed, fleeing northwards.[12][39]

To proceed further required ensuring the neutrality of the next empire, the Parthians whom Tigranes had also wooed. In 68 BC Lucullus made some advances into northern Armenia but was hampered by the weather and wintered in the south. His strategy had been to dismember Armenia into its former kingdoms. By 67 BC the Roman forces in Pontus were coming increasingly under attack by Mithridates who scored a major victory at Zela. Lucullus' troops were also tiring and becoming dissatisfied. Lucullus withdrew from Armenia but not in time to prevent the defeat at Zela.[40]

The failure of

The piracy strategy initiated by Servilius in 78–75 BC was suspended during the years of fighting Mithridates. Roman naval forces were defeated in 70 BC attempting to deal with the Cretan pirates, and the problem spread to Italy itself. A

Pompey's first move was to persuade the Parthians to harass Tigranes' eastern flank. Following Roman tradition he offered Mithridates terms, but he rejected these. consequently Pompey engaged him at the

Following the subdual of Armenia Pompey moved on to the Caucasus and the extreme end of Anatolia including

Provincialisation of Anatolia 133 BC – 114 AD

The Roman Republic's policy regarding expansion and overseas territory was frequently conflicted. There were those who were satisfied with diplomacy, creating allies on its borders that acted as buffer states against more distant threats. On the other hand, there were those who saw opportunities for glory and riches. central government in rome was often far from civil and military commanders in the field, and local ambitions often dragged Rome into expanding its frontiers. The military exploits of Lucullus and Pompey towards the end of the Mithridatic wars created an eastern expansion far beyond the vision of the Senate.

Policy in Anatolia had consisted of trade, influence and diplomacy with occasional military interventions to maintain the status quo when local kingdoms and empires became expansionist. That influence grew as Rome became the new superpower of the Mediterranean, and repeated interventions reduced many of the kingdoms in Anatolia to client state status. Sometimes Roman rule was forced on the republic by local events such as the bequeathing of kingdoms to Rome. Annexation of territory to form provinces was based on whether there was a trustworthy effective ruler who could rule in the interests of Rome or not.[42]

Formal Roman rule began when

Thus by Pompey's time the Roman provinces covered the west, north and south of Anatolia. In the centre

While much of Pontus ended up in the new province of Bithynia et Pontus, the east was divided into client kingdoms including Pontus, which continued until the last king, Polemon II (38–64 AD) was deposed by the Emperor Nero and Pontus became absorbed into the provincial system.

Cappadocia continued as an independent client, at one point being united with Pontus, until the Emperor Tiberius deposed the last monarch Archelaus (36 BC – 17 AD), creating a province of the same name.

Armenia continued as a client state after the Mithridatic wars, torn between Rome and Parthia, eventually becoming a province under the Emperor Trajan in 114 AD.

Lycia in the extreme southwest remained independent until 43 AD when it became a province, and was then merged with the Pamphylian region of Galatia to form Lycia et Pamphylia.

The Trumvirates and last years of the Republic 61–27 BC

In the year's following Pompey's departure the Roman administration in Anatolia kept a wary and at times fearful eye on Parthia on its eastern borders, while the central government in Rome was focussed on Julius Caesar and the events in Western Europe. There followed two centuries of conflict. In 53 BC Marcus Licinius Crassus led an expedition from Syria into Mesopotamia which proved disastrous, the Parthians inflicting huge losses at the Battle of Carrhae in which he was killed. Sporadic raids by the Parthians against Syria continued, but were repelled and suffered a major reversal in 51 BC. However, Crassus' death unbalanced the First Triumvirate of which he was a member, leading to the progressive difficulties between Pompey and Caesar.

The

Meanwhile, Caesar was planning to return to the east and deal with the Parthians who were once again harassing Syria, and avenge Crassius. Plans that were cut short by his assassination in 44 BC.[47]

With his death, Rome lapsed into yet another war, the

Armenia was granted to Alexander Helios and Syria and Cilicia to Ptolemy Philadelphus, while Antony retained Western Anatolia. Antony was defeated at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and died the following year.

Of the surviving client kingdoms, Cappadocia was the most prominent but was plagued by internal unrest requiring frequent Roman intervention, sometimes for lack of cooperation. At various times it acquired lesser Armenia and parts of Cilicia, and was unified with Pontus.

Roman Empire 27 BC – 4th century

The Empire: The Principate 27 BC – 193 AD

With Antony dead, and Lepidus marginalised, the second triumvirate was effectively dissolved, leaving Octavian as the sole power. Thus the republic came to and end. Octavian's powers progressively increased, he was granted the title Augustus by the Senate and adopted the title princeps senatus in 27 BC although technically a consul, and shortly after Imperator in effect Emperor and the first phase of the Roman Empire, the Principate (27 BC – 284 AD) was born. In exchange for this redistribution of powers, a long history of civil wars came to an end, replaced by the Augustan age (27 BC – 14 AD). The endless wars had been devastating for Asia Minor.[48]

Julio-Claudian dynasty 27 BC – 68 AD

Under Augustus, Galatia became a formal province in 25 BC strengthening direct Roman rule in western Anatolia, while in 27 BC Cilicia had been absorbed into Syria. Meanwhile, Cappadocia and Armenia continued as client states. A truce of sorts was worked out in 1 AD between the Romans and the Parthians. Augustus and his descendants formed the

Armenia continued to be a flashpoint between the Romans and Parthians. War erupted again in 36, and again in 58 under Nero (54–68). After a disastrous battle of Rhandeia in 62. A compromise was worked out with a Parthian on the Armenian throne subject to Roman approval.

The Year of Four Emperors and Flavian dynasty 69–96 AD

The Julio-Claudian dynasty ended with Nero's suicide, resulting in a period of instability in 69 until Vespasian (69–79) ascended, founding the Flavian dynasty. In 72 Vespasian united all the disparate elements of Cilicia into the Roman province, many of which had remained petty dynasties. Vespasian also created a new composite province of Lycia et Pamphylia in 72, out of Claudius' province of Lycia and the Pamphylia region of the province of Galatia.[50]

Nerva-Antonine dynasty 96–192 AD

Following the assassination of

Trajan's successor, Hadrian (117–138), decided not to persist with the eastern provinces, and Armenia continued to be a source of conflict in this period. Marcus Aurelius (161–180) was faced with yet another invasion by Parthia on assuming the Imperial office. The war lasted five years and again the Parthian capital was sacked. A new threat was the Antonine Plague (165–180), which severely affected Asia.

The Year of Five Emperors and Severan Dynasty 193–235 AD

The

In 193, the province of

The Empire: the years of crisis 235–284, Schism 258–274 and Gothic invasion (255)

The assassination of

Persia and the eastern front

During the crisis the eastern provinces felt they were on their own, and were not inclined to help prop up Rome against foreign attacks. The

The capture of Nicomedia and Chalcedon by the Goths forced Valerian (253–260) to move his main troop deployments to Cappadocia, weakening his efforts to contain the Sassanid threat. In the course of these latter campaigns, Valerian became the first Roman emperor to be captured by enemy forces, in 260. The Sassanid forces penetrated as far west as Isauria and Cappadocia. The major part of the Roman response fell to the forces in Syrian outpost, Valerian's successor, Gallienus (260–268), being preoccupied in the west. Asia Minor then experienced the combined attacks of the Danubian Goths in the Balkans pouring into Thrace, while their Black Sea relatives ravaged coastal cities. A later emperor, Carus (282–284), led an expedition east to restore Roman rule in Armenia and reverse earlier losses by taking on the Sassanids, but died on the campaign.[54]

Gothic invasion

A new problem for Anatolia emerged during this period, with the expansion of the

Schism, reunification and division

By 258 the empire was breaking up with the defection of the western

By the time of Carus, the idea of two empires, west and east was emerging. Carus appointed one of his sons, Carinus (282–285) as co-emperor for the western empire, while he and his other son, Numerian (283–284) concerned themselves with the east. Numerian died before returning west leaving Carinus to face a newly proclaimed emperor, Diocletian, who subsequently triumphed.

The Empire: the Dominate 284 – 4th century

The Tetrarchy and first Eastern Empire 284–324

Order and stability was restored when Diocletian (284–305) obtained power following the death of the last Crisis Emperors, Numerian (282–284), and overcoming his brother Carinus, ushering in the next and final phase of the Roman Empire, the Dominate.

Diocletian managed to secure the frontiers and instituted sweeping administrative reforms that affected all the

First Tetrarchy 293–305

This evolved into a tetrachy in 293, the empire being divided into four, but each Caesar reporting to an Augustus. The new co-emperors were Galerius and Constantius, forming the First Tetrarchy (293–305). Thus Diocletian and Maximian were the Augusti (senior emperors) with Galerius and Constantius as Caesares (junior emperors).

There were now four Tetrarchic Capitals, with the east being governed from

In the Diocletian reforms provinces were divided into smaller units, almost doubling the total number soon after 293, replicating the original regions of Asia Minor. Asia was divided into seven smaller provinces, and Bithynia three (Bithynia, Honorias and Paphlagonia). Galatia lost its northern and southern parts to the new provinces of Paphlagonia and Lycaonia, respectively. Lycia et Pamphylia was once again split into its two constituent units. Cappadocia lost its Pontic and Lesser Armenian territories. Another innovation was the establishment of Dioceses, an intermediate administrative structure that combined together several provinces, although Cicero used the term when he was governor of Cilicia (51 BC). Anatolia was restructured into three dioceses, which were eventually grouped under the Praetorian Prefecture of the East (praefectura praetorio Orientis); Asia (Asiana), Pontus (Pontica) and East (Oriens). (see navbox below)[59]

Armenia returned to the Roman sphere in 287 as a vassal state under Tiridates III (287–330) and more formally as protectorate in 299. On the eastern front, Persia renewed hostilities in 296, inflicting losses on Galerius' forces, until Diocletian brought in new troops from further west the following year and clashed with the Persians in lesser Armenia, and pursued them all the way to Ctesiphon in 298, effectively ending the campaign.[60]

Second Tetrarchy 305–308

In 305, both Augusti stepped down, an unprecedented constitutional step, the agreement being that both Caesares would be promoted to Augusti, and new Caesares appointed. This happened but the expected new Caesares were not, as expected, the sons of former emperors,

Constantius died in 306 and Galerius raised Severus to Augustus as expected. However, Constantine, who would have been eligible for the vacant role of Caesar, was elected as Augustus by his troops, in competition with Severus, while Maxentius the other overlooked candidate for Caesar simultaneously challenged Severus and indeed deposed and murdered him, declaring himself Augustus, while his father Maximian also attempted to return to power and take the role of Augustus. This left multiple candidates for the Tetrarchical roles.

Third Tetrarchy and civil war 308–313

In 308 Galerius and Diocletian attempted a diplomatic solution, summoning an Imperial Conference that elected Licinius as Augustus of the West, with Constantine as his Caesar, while the incumbents, Galerius and Maximinus continued in the east, as a Third Tetrarchy. this proved unworkable and both Maxentius and Constantine, originally overlooked as Caesares continued to stake their claims, and by 309 they became full Augusti and the empire dissolved into civil war between 309 and 313.

Relative to the western parts of the empire, the eastern empire was stable. The transition from Diocletian to Galerius proceeded smoothly in 305. Upon assuming the role of Augustus, Galerius assigned Maximinus to Egypt and Syria. On Galerius'death in 311, Maximinus divided the east seizing Asia Minor, with Licinius as western Augustus. When Maximinus fell out with Licinius, he crossed the

Diarchy 313–324

At the end of the wars there remained two empires and two emperors. Constantine had disposed of Maxentius in 312 and agreed to repartition the empire, with Constantine in the west and Licinius in the East. Licinius was immediately engaged in dealing with the Persian situation. By the following year (314) the two emperors were at war, which simmered over a decade. Constantine eventually besieged Licinius in Byzantium in 324, defeated his fleet at the

Constantinian dynasty 324–363

At the end of the 3rd century, the vast empire was beset by administrative and fiscal problems, and much of the power lay in the hands of the military, while there was no clear principle of succession and dynasties were short lived, their fate often determined by force of arms rather than legitimacy. The empire was divided culturally with Latin predominating in the west, and Greek in the east, while eastern ideas, such as

Constantine I 324–337

Constantine considered a number of candidate cities as a new eastern capital, before deciding on

Constantine's major contribution to religion in the empire was to summon the elders of the Christian world to the great

Constantine's administrative reforms included restructuring of the

During his reign, conflict with the Persians over Armenia persisted and he was planning a major campaign at the time of his death.

Constantine's successors

Constantine I's succession was complicated being succeeded by three of his sons simultaneously; Constantine II (337–340), Constantius II (337–361) and Constans (337–350). They immediately set about carving up Constantine's empire, together with their cousin Dalmatius, Anatolia falling to Constantius II. Constantius rarely visited Constantinople being preoccupied with the eastern front, amongst other wars. During Constantius' reign the Praetorian prefecture of the East was established, incorporating the eastern dioceses, with its headquarters in Constantinople,

By 350 both of Constantius II's brothers had died and the empire was reunited under him. Constantius continued the tradition of appointing Caesares, from his cousins. Of those

These were turbulent times, but from the rule of

Jovian and the Valentinians 363–378

Upon Julian's death, a military commander in his army,

Valens was faced with war on two fronts, with the Goths in the Balkans with whom he made a hasty peace in 369, so he could deal with the Persian attacks on Armenia. His problems were compounded by a revolt in

Valens split Cappadocia, already much diminished into two provinces, Cappadocia prima in the north and Cappadocia secunda in the southwest around Tyana.

For a brief time the empire was reunited (378–379) under the western emperor Gratian (375–383), son of Valentinian I and nephew of Valens, before he realised he needed someone to rule in the east separately, dispatching his brother in law, Theodosius I (379–395), to Constantinople. In the west the Valentinians continued in power until the death of Valentinian III (425–455).

Theodosian dynasty 378–455

Since Theodosius I (379–395) was only related to the Valentinians through marriage, he is regarded as the founder of a separate Theodosian dynasty. Like Constantine he is remembered in history as both Great and Saint. He was also the last emperor to rule over both east and west. He continued the tradition of co-rulers, appointing his son Arcadius as co-ruler (383–395).

The situation in the west was extremely complex. On the death of Valentinian I in 375,

Theodosius's major problems were with the Goths and his western frontier, which kept him away from Constantinople. He became notorious for his perpetration of the

Despite all these events he was able to contribute considerably to Anatolian life. The great

During the 4th century, most of the provinces making up the

Theodosius died in

Judaism and Christianity in Anatolia during Roman times

As the Roman Empire grew geographically it became increasingly diverse and the influence of many religions beyond the traditional Roman values was increasingly felt. Slowly a movement for religious tolerance developed.

Judaism

Jewish legend describes

The principal centres were

In the

Christianity

We have very little information regarding the spread of Christianity from the events recorded in

The 1st century

Paul came originally from

Paul noted that "all they which dwelt in Asia heard the word" and verified the existence of a church in

Even other non-Christians started to take notice of the new religion. In 112 the Roman governor in Bithynia writes to the Roman emperor Trajan that so many different people are flocking to Christianity, leaving the temples vacated.[78]

See also

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

- History of Anatolia

- Prehistory of Anatolia

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

- Ancient kingdoms of Anatolia

- Medieval states in Anatolia

References

- ^ ISBN 9781841763583.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57506-031-6

- ^ a b c Encyclopaedia Iranica: Achaemanid Satrapies

- ^ a b Botsford, George Willis (1922). Hellenic History. The Macmillan Company.

- ^ a b Aristodicus of Cyme and the Branchidae. Truesdell S. Brown. The American Journal of Philology Vol. 99, No. 1 (Spring, 1978), pp. 64–78

- ^ "The Works of Herodotus". MIT. 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ISBN 9780521762076.

- ^ a b Bury, John Bagnell (1913). A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great. Macmillan.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Iranica: Alexander the Great

- ^ Briant, P. "Des Achéménides aux rois hellénistiques: continuités et ruptures," Annali della Scuola di Pisa 9/4, 1979, pp. 1375–414)[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Shipley, Graham (2000) The Greek World After Alexander. Routledge History of the Ancient World. (Routledge, New York)

- ^ a b c d e f g Freeman (1999).

- ^ a b c Rawlinson, George (1900). Ancient History: From the Earliest Times to the Fall of the Western Empire. The Colonial Press.

- ^ Bevan, Edwyn Robert (1902). The House of Seleucus. E. Arnold.

- ^ Virtual Religion: Antiochus Hierax

- ^ Jona Lendering. "Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars". Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History online. vol. viii c. x

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-866172-6.

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. vii(i) 426 The Hellenistic World 1984

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. viii Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 B.C. 1989

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 b.c. 1992

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. vi 219 The Fourth Century B.C. 1994

- ^ a b Cambridge Ancient History vol. viii 335

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 259

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 263

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 135

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 266

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. viii 362

- ^ Encyclopédie méthodique: ou par ordre de matières: par une société de gens de lettres, de savans et d'artistes. Volume 2, Panckoucke, 1789 p. 462

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 269

- ^ a b Hornblower(1996).

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 140–2

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 142–3

- ^ H H Scullard, From Grachi to Nero p76

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 143–9

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 156–8

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 161–2

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 229–233

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 233–240

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 240–243

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 243–244, 248–259

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 260

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 266–269

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 269–270

- ^ Mitchell, Stephen (1995). Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor. Oxford University Press. p. 41.

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 265–6

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. ix 438

- ^ a b Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 645

- ^ Smith W (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography Walton and Maberly, London 1854 ii 659

- ^ S. Şahin – M. Adak, Stadiasmus Patarensis. Itinera Romana Provinciae Lyciae. İstanbul 2007; F. Onur, Two Procuratorian Inscriptions from Perge, Gephyra Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine 5 (2008), 53–66.

- ^ Five Good Emperors from UNRV History. Retrieved 2007-3-12.

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. 11 The High Empire, A.D. 70–192

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 28

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 42–46

- ISBN 9780300060621.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1952). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. William Benton. pp. 105–108.

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 54–55

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 58

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 76

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 81–83

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 87–88

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (1933). Byzantine Civilization. Methuen, London

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 90–92

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xii 98

- ^ Mommsen, Theodor (1906). The History of Rome: The Provinces, from Caesar to Diocletian. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Josephus, "Ant." xii. 3, § 4

- ^ a b Ramsay, W. M. (1904). The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia. Hodder & Stoughton. Archived from the original on 2018-04-19. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ Wilson, Michael. Cilicia:The First Christian Churches in Anatolia. Tyndale Bulletin 54.1 (2003) 15–30.

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 851

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 853

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 855

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 857

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 858

- ^ Early Christian Writings: Ignatius – The Epistle to the Magnesians

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. x 853, 858

- ^ Herbermann, Charles George (1913). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Co. pp. 788–789.

Sources

Reference works

- Cambridge Ancient History Online 14 vols. 1970–2000

Note: The original 11 vol.Cambridge Ancient History 1928–36 is now available as free ebooks - Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World. 10 vols.

- Hastings, James. A Dictionary of the Bible: Dealing with Its Language, Literature, and Contents, Including the Biblical Theology. Volume III: (Part I: Kir—Nympha). Minerva 2004 (reprinted from 1898). ISBN 9781410217264

- Hornblower, Simon; Antony Spawforth (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press Archived 2016-03-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- John Lemprière. A classical dictionary, containing a copious account of all the proper names mentioned in antient authors... 1839

- McEvedy, Colin (1967). The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History. Penguin.

- Marek, Christian (2010), Geschichte Kleinasiens in der Antike C. H. Beck, Munich, ).

- Smith W (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography Walton and Maberly, London 1854. 2 vols. Direct Link to Online Version

General

- Duncker, Max (1879). The History of Antiquity, Volume III. Richard Bentley & Son.

- Suthan, Resat (2009–2014). "Travels around Asia Minor 1976–2002. Anatoliaa: Historical". Thracian Ltd.

Classical period

- ISBN 0-19-872194-3.

- Ramsay, W.M. (1904). The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Shipley, Graham (2000) The Greek World After Alexander. Routledge History of the Ancient World. (Routledge, New York)

Hellenistic

- Bevan, Edwyn Robert (1902). The House of Seleucus. E. Arnold.

- Botsford, George Willis (1922). Hellenic History. The Macmillan Company.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1913). A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great. Macmillan.

Persian

- ISBN 978-1-57506-031-6Originally published in French as Histoire de l'Empire perse, Fayard, Paris, 1996

- Encyclopaedia Iranica

- Amélie Kuhrt. The Persian Empire. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0-415-43628-1, 9780415436281

- Philip De Souza. The Greek and Persian Wars 499–386 BC, Volume 36 of Essential histories. Osprey Publishing, 2003, ISBN 9781841763583

Roman

- Mommsen, Theodor (1906). The History of Rome: The Provinces, from Caesar to Diocletian. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Runciman, Steven (1933). Byzantine Civilization. Methuen, London.

External links

Media related to Classical Anatolia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Classical Anatolia at Wikimedia Commons