Hindu–Arabic numeral system

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system (also known as the Indo-Arabic numeral system,

The system was invented between the 1st and 4th centuries by

It is based upon ten glyphs representing the numbers from zero to nine, and allows representing any natural number by a unique sequence of these glyphs. The symbols (glyphs) used to represent the system are in principle independent of the system itself. The glyphs in actual use are descended from Brahmi numerals and have split into various typographical variants since the Middle Ages.

These symbol sets can be divided into three main families:

Origins

Sometime around 600 CE, a change began in the writing of dates in the Brāhmī-derived scripts of India and Southeast Asia, transforming from an additive system with separate numerals for numbers of different magnitudes to a positional place-value system with a single set of glyphs for 1–9 and a dot for zero, gradually displacing additive expressions of numerals over the following several centuries.[5] This Indian numeral system was the first featuring the combination of ciphering, positional notation, zero, and a decimal base.

When this system was adopted and extended by medieval Arabs and Persians, they called it al-ḥisāb al-hindī ("Indian arithmetic"). These numerals were gradually adopted in Europe starting around the 10th century, probably transmitted by Arab merchants;[6] medieval and Renaissance European mathematicians generally recognized them as Indian in origin,[7] however a few influential sources credited them to the Arabs, and they eventually came to be generally known as "Arabic numerals" in Europe.[8] According to some sources, this number system may have originated in Chinese Shang numerals (1200 BC), which was also a decimal positional numeral system.[9]

Positional notation

The Hindu–Arabic system is designed for

Although generally found in text written with the Arabic abjad ("alphabet"), numbers written with these numerals also place the most-significant digit to the left, so they read from left to right (though digits are not always said in order from most to least significant[10]). The requisite changes in reading direction are found in text that mixes left-to-right writing systems with right-to-left systems.

Symbols

Various symbol sets are used to represent numbers in the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, most of which developed from the

The symbols used to represent the system have split into various typographical variants since the Middle Ages, arranged in three main groups:

- The widespread Western "Arabic numerals" used with the Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek alphabets in the table, descended from the "West Arabic numerals" which were developed in al-Andalus and the Maghreb (there are two typographic styles for rendering western Arabic numerals, known as lining figures and text figures).

- The "Arabic–Indic" or "Eastern Arabic numerals" used with Arabic script, developed primarily in what is now Iraq.[citation needed] A variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals is used in Persian and Urdu.

- The Brahmic familyin India and Southeast Asia. Each of the roughly dozen major scripts of India has its own numeral glyphs (as one will note when perusing Unicode character charts).

Glyph comparison

| Symbol | Used with scripts | Numerals | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Arabic, Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek | Arabic numerals |

| ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | Arabic | Eastern Arabic numerals |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Persian / Dari / Pashto | |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Urdu / Shahmukhi | |

| ⠚ | ⠁ | ⠃ | ⠉ | ⠙ | ⠑ | ⠋ | ⠛ | ⠓ | ⠊ | Braille | Braille numerals |

| 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 | Brahmi | Brahmi numerals |

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ | Devanagari | Devanagari numerals |

| ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ | Tamil | Tamil numerals |

| ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | Eastern Nagari | Bengali numerals

|

| 𐴰 | 𐴱 | 𐴲 | 𐴳 | 𐴴 | 𐴵 | 𐴶 | 𐴷 | 𐴸 | 𐴹 | Hanifi Rohingya | Hanifi Rohingya script § Numbers |

| ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | Gurmukhi | Gurmukhi numerals

|

| ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ | Gujarati | Gujarati numerals |

| 𑙐 | 𑙑 | 𑙒 | 𑙓 | 𑙔 | 𑙕 | 𑙖 | 𑙗 | 𑙘 | 𑙙 | Modi | Modi numerals |

| 𑋰 | 𑋱 | 𑋲 | 𑋳 | 𑋴 | 𑋵 | 𑋶 | 𑋷 | 𑋸 | 𑋹 | Khudabadi | Khudabadi script § Numerals |

| ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ | Odia | Odia numerals |

| ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ | Santali | Santali numerals |

| 𑇐 | 𑇑 | 𑇒 | 𑇓 | 𑇔 | 𑇕 | 𑇖 | 𑇗 | 𑇘 | 𑇙 | Sharada | Sharada numerals |

| ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ | Telugu | Telugu script § Numerals |

| ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ | Kannada | Kannada script § Numerals |

| ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ | Malayalam | Malayalam numerals |

| ꯰ | ꯱ | ꯲ | ꯳ | ꯴ | ꯵ | ꯶ | ꯷ | ꯸ | ꯹ | Meitei | Meitei script § Numerals |

| ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ | Sinhala | Sinhala numerals |

| 𑓐 | 𑓑 | 𑓒 | 𑓓 | 𑓔 | 𑓕 | 𑓖 | 𑓗 | 𑓘 | 𑓙 | Tirhuta Mithilakshar | Maithili numerals |

| ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ | Tibetan | Tibetan numerals |

| ᥆ | ᥇ | ᥈ | ᥉ | ᥊ | ᥋ | ᥌ | ᥍ | ᥎ | ᥏ | Limbu | Limbu script § Digits |

| ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ | Burmese |

Burmese numerals |

| ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | Mongolian | Mongolian numerals |

| ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ | Khmer | Khmer numerals |

| ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ | Thai | Thai numerals |

| ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ | Lao | Lao script § Numerals |

| ᧐ | ᧑/᧚ | ᧒ | ᧓ | ᧔ | ᧕ | ᧖ | ᧗ | ᧘ | ᧙ | New Tai Lue |

New Tai Lue script § Digits

|

| ꩐ | ꩑ | ꩒ | ꩓ | ꩔ | ꩕ | ꩖ | ꩗ | ꩘ | ꩙ | Cham | Cham script § Numerals |

| 𑽐 | 𑽑 | 𑽒 | 𑽓 | 𑽔 | 𑽕 | 𑽖 | 𑽗 | 𑽘 | 𑽙 | Kawi | Kawi script § Digits |

| ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ | Javanese | Javanese numerals |

| ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ | Balinese | Balinese numerals |

| ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ | Sundanese | Sundanese numerals |

History

Predecessors

The

The actual numeral system, including positional notation and use of zero, is in principle independent of the glyphs used, and significantly younger than the Brahmi numerals.

Development

The place-value system is used in the

The first dated and undisputed inscription showing the use of a symbol for zero appears on a stone inscription found at the Chaturbhuja Temple at Gwalior in India, dated 876.[14]

Medieval Islamic world

These Indian developments were taken up in

In 10th century

The numeral system came to be known to both the

Adoption in Europe

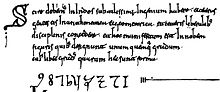

In Christian Europe, the first mention and representation of Hindu–Arabic numerals (from one to nine, without zero), is in the

Leonardo Fibonacci brought this system to Europe. His book Liber Abaci introduced Modus Indorum (the method of the Indians), today known as Hindu–Arabic numeral system or base-10 positional notation, the use of zero, and the decimal place system to the Latin world. The numeral system came to be called "Arabic" by the Europeans. It was used in European mathematics from the 12th century, and entered common use from the 15th century to replace Roman numerals.[20][21]

The familiar shape of the Western Arabic glyphs as now used with the Latin alphabet (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) are the product of the late 15th to early 16th century, when they entered early typesetting. Muslim scientists used the

-

Gregor Reisch, Madame Arithmatica, 1508

-

A calculation table, used for arithmetic using Roman numerals

-

Adam Ries, Rechenung auff der linihen und federn, 1522

-

Two arithmetic books published in 1514 – Köbel (left) using a calculation table and Böschenteyn using numerals

-

Adam Ries, Rechenung auff der linihen und federn (2nd Ed.), 1525

-

Robert Recorde, The ground of artes, 1543

-

Peter Apian, Kaufmanns Rechnung, 1527

-

Adam Ries, Rechenung auff der linihen und federn (2nd Ed.), 1525

Adoption in East Asia

In AD 690, Empress Wu promulgated Zetian characters, one of which was "〇". The word is now used as a synonym for the number zero.

In China, Gautama Siddha introduced Hindu numerals with zero in 718, but Chinese mathematicians did not find them useful, as they had already had the decimal positional counting rods.[22][23]

In Chinese numerals, a circle (〇) is used to write zero in

Chinese and Japanese finally adopted the Hindu–Arabic numerals in the 19th century, abandoning counting rods.

Spread of the Western Arabic variant

The "Western Arabic" numerals as they were in common use in Europe since the

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Audun Holme, Geometry: Our Cultural Heritage, 2000

- ^ William Darrach Halsey, Emanuel Friedman (1983). Collier's Encyclopedia, with bibliography and index.

When the Arabian empire was expanding and contact was made with India, the Hindu numeral system and the early algorithms were adopted by the Arabs

- ISBN 978-1-4042-0513-0

- ISSN 0394-7394.

- ^ Chrisomalis 2010, pp. 194–197.

- ^ Smith & Karpinski 1911, Ch. 7, pp. 99–127.

- ^ Smith & Karpinski 1911, p. 2.

- ^ Of particular note is Johannes de Sacrobosco's 13th century Algorismus, which was extremely popular and influential. See Smith & Karpinski 1911, pp. 134–135.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ^ In German, a number like 21 is said like "one and twenty", as though being read from right to left. In Biblical Hebrew, this is sometimes done even with larger numbers, as in Esther 1:1, which literally says, "Ahasuerus which reigned from India even unto Ethiopia, over seven and twenty and a hundred provinces".

- ^ Flegg 1984, p. 67ff..

- ^ Pearce, Ian (May 2002). "The Bakhshali manuscript". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Ifrah, G. The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer. John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2000. Translated from the French by David Bellos, E.F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk

- Bill Casselman (February 2007). "All for Nought". Feature Column. AMS.

- ^ al-Qifti's Chronology of the scholars (early 13th century):

- ... a person from India presented himself before the Caliph al-Mansurin the year 776 who was well versed in the siddhanta method of calculation related to the movement of the heavenly bodies, and having ways of calculating equations based on the half-chord [essentially the sine] calculated in half-degrees ... Al-Mansur ordered this book to be translated into Arabic, and a work to be written, based on the translation, to give the Arabs a solid base for calculating the movements of the planets ...

- ... a person from India presented himself before the

- ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4939-3780-6.

- ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ^ Martin Levey and Marvin Petruck, Principles of Hindu Reckoning, translation of Kushyar ibn Labban Kitab fi usul hisab al-hind, p. 3, University of Wisconsin Press, 1965

- ^ "Fibonacci Numbers". www.halexandria.org.

- ^ HLeonardo Pisano: "Contributions to number theory". Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2006. p. 3. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

- ^ a b Qian, Baocong (1964), Zhongguo Shuxue Shi (The history of Chinese mathematics), Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe

- ISBN 4-88595-226-3

Bibliography

- Chrisomalis, Stephen (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87818-0.

- Flegg, Graham (1984). Numbers: Their History and Meaning. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-022564-8.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (2001). "The Arabic numeral system". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (2000). "Indian numerals". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- Smith, David Eugene; Karpinski, Louis Charles (1911). The Hindu–Arabic Numerals. Boston: Ginn.

Further reading

- Menninger, Karl W. (1969). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13040-8.

- On the genealogy of modern numerals by Edward Clive Bayley

![A calculation table [de], used for arithmetic using Roman numerals](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/Rechentisch.png/120px-Rechentisch.png)