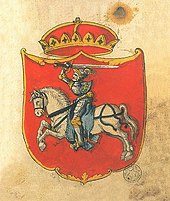

Coat of arms of Lithuania

| Coat of arms of Lithuania Lietuvos herbas Vytis (Pogonia, Pahonia) | ||

|---|---|---|

Shield Gules, an armoured knight armed cap-à-pie mounted on a horse salient holding in his dexter hand a sword Argent above his head. A shield Azure hangs on the sinister shoulder charged with a double cross (Cross of Lorraine) Or. The horse saddles, straps, and belts Azure. The hilt of the sword and the fastening of the sheath, the stirrups, the curb bits of the bridle, the horseshoes, as well as the decoration of the harness, all Or. | | |

| Earlier version(s) | see below | |

The coat of arms of Lithuania is a

The once powerful and vast Lithuanian state,

The ruling

Blazoning

The

| Variants employed by institutions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| President | Seimas | Ministry of Agriculture | Ministry of the Interior | Police | Ministry of National Defence |

Names of the coat of arms

In early heraldry, a knight on horseback is usually depicted as ready to defend himself and is not yet called Vytis.[2] It is unknown for certain what Lithuania's coat of arms was initially called.[26][27]

Lithuanian language

The origins of the Lithuanian proper noun Vytis are also unclear. At the dawn of the Lithuanian National Revival, Simonas Daukantas employed the term vytis, referring not to the Lithuanian coat of arms, but to the knight, for the first time in his historical piece Budą Senowęs Lietuwiû kalneniu ir Żemaitiû, published in 1846.[28][29] The etymology of this particular word is not universally accepted; it is either a direct translation of the Polish Pogoń, a common noun constructed from the Lithuanian verb vyti ("to chase"), or, less likely, a derivative from the East Slavic vityaz. In western South Slavic languages (Slovenian, Croatian/Serbian/Montenegrin and Macedonian) and Hungarian, vitez denotes the lowest feudal rank, a knight.[30] According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, vitez is derived from the Old High German word Witing.[31]

The first presumption, raised by the linguist Pranas Skardžius in 1937, is challenged by some, as Pogoń does not mean "chasing (knight)".[32] In support of the second proposal, the Lithuanian language has words with the stem -vyt in personal names like Vytenis; furthermore, vytis has a structure common to words derived from verbs.[33] According to professor Leszek Bednarczuk, there existed a derivative word vỹtis, vỹčio in the Old Lithuanian language, which translates to English as pursuit (from persekiojimas), chase (from vijimasis).[32]

For the 13th century the Old Prussian word vitingas is attested, meaning "knight" or "nobleman".[34] In today's Lithuania, it can be found in place names, personal names and action verbs.[34] So it is possible that in the Old Lithuanian language there was a similar word describing act of chasing an enemy or an armed horseman chasing an enemy.[34] Another possibility is that Grand Duke Vytenis name is derived from the Old Prussian word vitingas.[6] Therefore, Vytenis' reign (1295–1316) is also associated with the word Vytis as the Ruthenian Hypatian Codex[35] mentions that after beginning to rule the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 13th century, he came up with a seal with an armored horseman and a sword raised above his head (in the Codex's original Old Church Slavonic it is written that Vytenis named it Pogonia[6]).[36][37][38][39][4]

Several historical sources mention place names which names are probably derived from the Vytis word.[6]

A Teutonic source, probably dating from the late 14th century

In the 17th century in his Polish-Latin-Lithuanian dictionary Konstantinas Sirvydas translated the Polish word Pogonia in the sense of the person doing the chasing into Lithuanian as Waykitoias, and in the sense of the act of chasing as Waykimas. Today Waykimas (Vaikymas in the modern Lithuanian orthography) is considered to be the earliest known Lithuanian language name for the coat of arms of Lithuania.[2][46][47][48] Waykimas was also used into the 19th century,[47] together with another Lithuanian name – Pagaunia.[citation needed]

In 1884,

Slavic languages

The words pogoń and pogonia have been known in Polish since the 14th century in the sense of "pursuit"[51] or the legal obligation to chase fleeing opponent.[52] It was not until the 16th century that the use of the word appeared to describe an armed horseman.[53][54]

The word came into heraldic use in 1434, when King Władysław II granted a coat of arms with this name (Pogonya) to Mikołaj, the mayor of Lelów. The coat of arms depicted a hand wielding a sword emerging from a cloud. The resemblance to the Lithuanian coat of arms of the king is obvious, so it is possible that it was an abatement of the ruler's coat of arms.[51] The word pogonia to describe the Lithuanian coat of arms in the Polish language for the first time appears in Marcin Bielski's chronicle, published in 1551. However, Bielski makes a mistake, and speaking about the Lithuanian coat of arms he describes Polish noble coat of arms: "From this custom Lithuanian principality uses Pogonia as its coat of arms, that is an armed hand passes a bare sword".[55][56] The term gradually became established with the spread of the Polish language and culture.[2][8][29][54] Pogonia is also found in Prince Roman Sanguszko's documents from 1558 and 1564.[54]

The emblem was described a century earlier, in a document of Supreme Duke

Possible early beginnings

The leader of

Lithuanian mythologists believe that the bright rider on the

, a god of war, which is commonly depicted as a horserider.Emblems of Lithuania's rulers (before 1400)

The old Lithuanian heraldry of the

The second redaction of the Lithuanian Chronicles, compiled in the 1520s at the court of Albertas Goštautas mentions that semi-legendary Grand Duke Narimantas (late 13th century) was the first Grand Duke to adopt knight on horseback as his and the Grand Duchy's coat of arms. It describes it as an armed man on a white horse, on the red field, with a naked sword over his head as if he was chasing someone, as the author explains that is why it is called "погоня" (pohonia).[21][71] A slightly later edition of the chronicle, so-called Bychowiec Chronicle, tells a similar story, without mentioning coat of arms name: "when Narimantas took the throne of the Grand Duke of Lithuania, he handed his Centaur coat of arms to his brothers and made a coat of arms of a rider with a sword for himself. This coat of arms indicates a mature ruler capable of defending his homeland with a sword".[4][72]

The legend of the adoption of the Lithuanian coat of arms at the time of Narimantas in the version of Bychowiec Chronicle is repeated by later authors: Augustinus Rotundus, Maciej Stryjkowski, Bartosz Paprocki and later historians and heraldists of the 17th and 18th centuries.[73]

Symbols of Mindaugas

We do not know the symbols used by the first rulers of Lithuania. One of the few relics that have survived to our times is the

In 1263, following the assassination of King Mindaugas and his family members by Daumantas and Treniota, Lithuania suffered internal disorder as three of his successors: Treniota, his son-in-law Švarnas, and his son Vaišvilkas were assassinated during the next seven years. Stability returned with Traidenis' reign, designated Grand Duke c. 1270.[77] At a similar time, the ancient Lithuanian capital Kernavė was first mentioned in 1279 in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle by noting that the Livonian Order's army devastated an area in King Traidenis' lands, which was their main objective (part of early military clashes prior to the Lithuanian Crusade).[78] The coat of arms, seals or symbols of Traidenis are unknown.[79] However, archaeological findings in the 13th and 14th century necropolis in Kernavė offer an astounding variety of symbols and ornaments, of which plants, herbs, palmettes motifs, and suns (swastikas) are one of the most distinct symbols, depicted on the discovered headbands and rings, dating to the pagan period before the Christianization of Lithuania.[79]

Symbols of Gediminas

Grand Duke Gediminas's authentic symbols did not survive to this day. On 18 July 1323 in Lübeck imperial scribe John of Bremen made a copy of three letters sent by Gediminas on 26 May to the recipients in Saxony.[80] According to the notary's transcript, the oval seal of Gediminas had a twelve corners edging, at the middle of the edging was an image of a man with long hairs, who sat on a throne and held a crown (or a wreath) in his right hand and a sceptre in his left hand, moreover, a cross was engraved around the man along with a Gediminas' title in Latin.[81][82][83]

Symbols on coins of Vytautas and Jogaila

The Lithuanian dukes and

The Treasure of Verkiai, discovered in 1941, has 1983 coins of Vytautas the Great which resembles the Pečat-type coins, however, they likely have a crossbow bolt (instead of an arrowhead or a spearhead) and a cross on one side and the Columns of Gediminas on the other side, thus they presumably have been minted later than the Pečat-type coins.[96][97] Quite a lot of such coins of Vytautas the Great were also found in other places of Lithuania (mostly in the southeastern and central part, but also in Samogitia), Ukraine (especially in Volhynia), and Belarus.[98] In comparison, coins attributed to Jogaila, which have a similar appearance to the Pečat'-type coins, has a spearhead and a cross on one side and the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians (Polish: Bojcza) in a shield on the other side.[96]

Following the Christianization of Lithuania, in circa 1388, Grand Duke Jogaila minted new coins: with a fish rolled into a ring (Christian sign of the fish) and inscription КНѦЗЬ ЮГА (Duke Jogaila) on the obverse and with a Double Cross of the Jagiellonians in a shield on the reverse.[93] It is believed that such coins were minted to commemorate the Christianization of Lithuania and the Christian sign of the fish could have been chosen when Pope Urban VI officially recognized Lithuania as a Catholic state (such recognition occurred on 17 April 1388).[93] Nevertheless, a fish–blossom symbol, depicted on the coins, can also be associated with an earlier date of 11 March 1388 when Pope Urban VI recognized the Roman Catholic Diocese of Vilnius, which was established by Grand Duke Jogaila.[93] In any case, the main purpose of this symbol was to showcase the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a Catholic state, recognized and under the auspices of the Pope.[93] Lithuania was the last state in Europe to be Christianized.[99]

Knight on horseback

The

The establishment of the sword in the heraldry of the Lithuanian rulers is related to the ideological changes of the ruling

-

Seal of duke Lengvenis, 1379

-

LithuanianDenarof Jogaila with horseman, minted in the 14th century

-

Seal of Jogaila, 1386

-

Seal of Kaributas, 1386

-

Seal of Skirgaila, 1387

-

Seal of Vytautas the Great, 1385

-

Seal of Vytautas the Great, 1390 (1842)

-

Lithuanian Vytis (Waykimas) on Tenebrat Bell (which was possibly funded by Jogaila in circa 1388) of St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków[108]

-

Lithuanian Groschen of Jogaila with the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians and Lithuanian Vytis (Waykimas), minted between 1392 and 1434

-

The equestrian image of Jogaila in the Chapel of the Holy Trinity, Lublin Castle, painted in ~1407

Columns of Gediminas

The Columns of Gediminas are one of the earliest surviving

In heraldry, the Columns of Gediminas were usually pictured in gold or yellow on a red field, while they were occasionally portrayed in silver or white since the second half of the 16th century.

Compared to the Double Cross of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the Columns of the Gediminids had been used more predominantly in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[23] The Columns of the Gediminids were featured on the Lithuanian coins of the 14th and subsequent centuries; the banners of the regiments led by Grand Duke Vytautas at the Battle of Grunwald; the 15th and 16th century church paraphernalia given to Vilnius Cathedral; the 15th century seals of the Lithuanian Franciscans and major state seals in 1581–1795; book graphics; and the pieces of work by Vilnius' goldsmiths.[23][112][113] Combined with the knight on horseback, the Columns of Gediminas were also embedded on the Lithuanian cannon barrels in the 16th and 17th centuries.[23] The symbol also decorated horse bridles and landmarks of the dominions of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania.[23] In 1572, after the death of the last male Gediminid descendant, Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus, the Columns of Gedimimas remained in the insignias of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as the secondary (alongside the knight on horseback) coat of arms of the state.[109] In later years, the Columns of Gediminas were called simply as the Columns (it is known from the early 16th century sources).[109]

Official coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

15th century

- Coats of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the time of Kęstutaičiai rule

-

Seal of Vytautas the Great with the Lithuanian coat of arms, featuring horseman, in his left hand, circa 14th–15th centuries

-

Seal of Vytautas the Great with Vytis (Waykimas), which features the Columns of Gediminas on the shield, 1404

-

Seal of Vytautas the Great with Vytis and coats of arms of his ruled lands, 1404 (1841)

-

One of the earliest surviving depictions of Vytis (Waykimas) in a flag of Vytautas the Great. Painted in 1416 by a Portuguese herald, who attended the Council of Constance.[114]

-

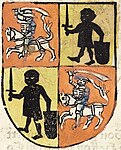

Coat of arms of Vytautas the Great, which features the standing knight of Kęstutaičiai and Vytis (Waykimas), used during the Council of Constance. Painted by Ulrich of Richenthal, 15th century.

-

Duke Sigismund Korybut and his troops flying the Lithuanian banner of arms in Prague, 15th century

-

Seal of Sigismund Kęstutaitis with Vytis (Waykimas) in his left hand, 15th century

-

Vytis with Columns of Gediminas from the 15th-century Codex Bergshammar. Attributed to Grand Duke Sigismund Kęstutaitis.

The meaning of the Lithuanian ruler's coat of arms and the coat of arms of the Lithuanian state was given to the horseman not by Jogaila, but by his cousin, the Grand Duke Vytautas the Great.[2] Firstly, around 1382, he changed the infantry on his coat of arms, inherited from his father Grand Duke Kęstutis, to a horseman, then made the portrait heraldic – in Vytautas' majestic seal (early 15th century), he is surrounded by the coat of arms of lands belonging to him, in one hand he holds a sword, which represents the power of the Grand Duke of Lithuania, in the other hand – a raised shield (on which a horseman is depicted), which, like an apple of royal power, symbolizes the Lithuanian state ruled by him.[2][66] Furthermore, Vytautas the Great minted coins with the horseman on one side and the Columns of Gediminas on the other side.[84]

In the 15th century,

The history between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Lithuanian

At the end of the 14th century, the knight on horseback appeared on the first Lithuanian coins, however, this figure had not yet fully formed, therefore in some coins, the knight is depicted as riding to the left, in others – to the right.[3] In some he holds a spear while others depict a sword; the horse can either be standing in place or galloping.[3] The Double Cross was used in isolation on the Lithuanian coins of the late 14th century and on the banner of the royal court referred to in the Lithuanian language as Gončia (English: The Chaser).[24]

During Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon's reign in Lithuania from 1492 to 1506, the depiction of the knight's direction was established – the horse was always galloping to the left (in the heraldic sense – to the right).[3] Also, the knight was for the first time depicted with a scabbard, while the horse – with a horse harness, however, the knight does not yet have on his shoulder a shield with the double-cross of the Jagiellonian dynasty.[3] Moreover, Alexander's coins also depict an eagle as the symbol of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania's dynastic claim to the Polish throne.[3] During the reign of Grand Duke Sigismund I the Old, who ruled Lithuania from 1506 to 1544, the image of the horseman was moved to the other side of the coins – the reverse, thus marking that it was the coin of Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[3] The knight was also for the first time depicted with a shield with the Double-Cross of the Jagiellonian dynasty.[3] In heraldry, such an image of the horseman is only associated with the Lithuanian state.[3] In the 15th century, the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians became an integral part of the Lithuanian coat of arms and was started to be depicted on the horseman's shield.[121]

At the beginning of the 15th century, the colors and composition of the seal became uniform: on a red field a white (silver) charging knight with a sword raised above his head, with a blue shield with a Double Golden Cross to his left shoulder (during the reign of Kęstutaičiai dynasty – red shield with the golden Columns of Gediminas[122]); horse bridles, leather belts and a short girdle – colored in blue.[2][49][123] Metals (gold and silver) and the two most important colors of medieval coats of arms were used for the Lithuanian coat of arms – Gules (red) then meant material, or earthly (life, courage, blood), Azure (blue) – spiritual, or heavenly (heaven, divine wisdom, mind) values.[2][49]

- Lithuanian coats of arms during the rest of the 15th century

-

Royal Seal of Jogaila which features Vytis (Waykimas)

-

Flag of Jogaila with the Polish Eagle and Vytis (Waykimas), used during the Council of Constance in 1416

-

Vytis (Waykimas) on the tomb monument of Jogaila in the Wawel Cathedral

-

Lithuanian coat of arms, dating to 1475, which, judging from its archaic look, was likely redrawn from an even earlier painting[114]

-

Lithuanian Denar of Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon with horseman and the Columns of Gediminas, 15th century

-

Columns of Gediminas from the 15th-century Codex Bergshammar

-

Half-Groschen of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon with Vytis (Waykimas) from the late 15th century or early 16th century

16th century

Only in the 16th century a distinction between the ruler (Grand Duke) and state emerged (it was the same entity previously), from which time one also finds mention of a state flag.[115] In 1578, Alexander Guagnini was the first to describe such a state flag, according to him the state flag of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was made of red silk and had four tails, its principal side, to the right of the flag staff, was charged with a white mounted knight underneath the ducal crown; the other side bore an image of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[115] The highly revered Blessed Virgin Mary was considered the patron saint of the state of Lithuania, and even the most prominent state dignitaries favoured her image on their flags, thus the saying: "Lithuania – land of Mary".[115] Later only the knight is mentioned embroidered on both sides of the state flag.[115]

After the

In 1572, following the death of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus, the last male descendant of the Jagiellonian dynasty as he did not leave any male heir to the throne, the Double Cross remained as a symbol in the national coat of arms and was started to be referred to as simply the Cross of Vytis (Waykimas) after losing the connection with the dynasty.[24]

- 16th-century depictions of the Lithuanian coats of arms

-

Coat of arms of Lithuania Vytis (Waykimas), depicted in the Coat of arms of Grand Duke Aleksandras Jogailaitis, 1501.

-

A 1506 depiction of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon in the Polish Senate, surrounded by Lithuanian and Polish coat of arms, one of them are the golden Columns of Gediminas

-

The Great Seal of Lithuania with Vytis (Waykimas) in the centre, belonging to Sigismund I the Old, 1529

-

The first page of the Latin copy of Laurentius (1531) of the First Statute of Lithuania. Vytis (Waykimas) is drawn on a damasked shield.

-

A 1568 Lithuanian coin of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus with Gediminas' Cap, horseman and Columns of Gediminas

-

Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with Vytis (Waykimas), decorated with the Columns of Gediminas, used during the reign of Grand Duke Stephen Báthory

-

Vytis (Pogonia) on the Sigismund III Vasa Tower (1595) of theJagiellonians

17th century to 1795

- 17th-century coats of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

-

Authentic Vytis (Waykimas) depicted on the Gate of Dawn, which survived annexations

-

Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the reign of the Vasa dynasty

-

Authentic Vytis (Waykimas) depicted on the outer wall of the Chapel of Saint Casimir

-

Coin of 15 golden Ducats of Grand Duke Sigismund III Vasa with Vytis (Waykimas), 1617

-

The Great Seal of Lithuania with Vytis (Waykimas) and Columns of Gediminas, belonging to Władysław IV Vasa

-

Coin of Grand Duke John III Sobieski with Vytis (Waykimas) and the Polish Eagle, 1684

The Renaissance introduced minor stylistic changes and variations: long feathers waving from the tip of the knight's helm, a long saddle-cloth, the horsetail turned upwards and shaped as nosegay. With these changes, the red flag with its white knight survived until the end of the 18th century and Grand Duke Stanislaus II Augustus was the last Grand Duke of Lithuania to employ it.[115] His flag was colored in crimson, had two tails, and was decorated with the knight on one side and the ruler's monogram – SAR (Stanislaus Augustus Rex) on the other side.[115] SAR monogram was also inscribed on the flagpole finial.[115] In 1795, after the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Grand Duchy of Lithuania was annexed to the Russian Empire, with a smaller part going to the Kingdom of Prussia, and traditional coat of arms of Lithuania, which represented the state for more than four centuries, was abolished and the Russification of Lithuania was imposed.[2]

- 18th-century Lithuanian coats of arms

-

Thaler of Grand Duke Augustus II the Strong with Vytis (Waykimas), 1702

-

Coin of 10 golden Ducats of Grand Duke Augustus III with Vytis (Waykimas), 1756

-

Seal of theTreasuryof Lithuania, 18th century

-

Coat of arms of the Vilnius University, 1707

-

Coats of arms on the Dresden Cathedral in Dresden, 18th century

-

Authentic Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth on the Dominican Church of the Holy Spirit in Vilnius

-

Wall fragment with the Polish–Lithuanian coat of arms in the New Grodno Castle, built in the early 18th century

-

The 1st Lithuanian National Cavalry Brigade's Grand Seal (late 18th century)

-

Coat of arms in the Warsaw Royal Castle, 18th century

-

Handle of the ceremonial sword of Stanislaus II August Poniatowski, 18th century

-

Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, used during the reign of Stanislaus II Augustus, 1764–1795

-

Lithuanian coat of arms with the Jagiellonian Double Cross, depicted by Franz Johann Joseph von Reilly in 1793

1795–1918

At first, the charging knight was interpreted as the country's ruler. As time passed, he became a knight who is chasing intruders out of his native country. Such an interpretation was especially popular in the 19th century, and the first half of the 20th century, when Lithuania was part of the Russian Empire and sought its independence.[2] During the Lithuanian National Revival in the 19th century, Lithuanian intellectuals Teodor Narbutt and Simonas Daukantas claimed that the reviving Lithuanian nation is the inheritor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania heritage, including the Lithuanian coat of arms Vytis (Waykimas), which was widely used in their organized events.[126]

19th-century anti-Russian uprisings

Uprisings to restore the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth like the 1830–31

- Lithuanian coats of arms during the Uprisings of 1830–1831 and 1863–1864

-

Coat of arms of the November Uprising, 1830–31

-

Banner with emblem of the November Uprising, 1830—31

-

The Provisional Government in Warsaw reintroduced Vytis (Pogonia) and Eagle on the coins and banknotes during the 1830–31 November Uprising

-

Painting commemorating Polish–Lithuanian union; ca. 1861. The motto reads "Eternal union".

-

Emblem of the January Uprising, 1863–64

-

Cartouche with the coat of arms of the January Uprising, 19th century

The 1863–64 January Uprising spread especially wide in the

In the Russian Empire (1795–1915)

Following the partition of the

- Use of the Lithuanian coats of arms in the Russian Empire

-

Coats of arms with Vytis, which incorporated (near the top) into the Greater Coat of Arms of the Russian Empire, 19th century

-

The White Columns of Vilnius (1818–1840) with Vytis (Pogonia), which were later replaced with the double-headed eagles

-

Insignia of the Life-Guards Lithuanian Regiment

-

Mosaics featuring the coats of arms with Vytis on the Church of the Savior on Blood in Saint Petersburg, completed in 1907

-

Seals of the Vilnius University, mid-19th century

-

Hand rail decorations with Vytis on the Pilies (Castle) Bridge in Vilnius

-

Column with Vytis in Trakai, 1910

However, in 1845 Tsar Nicholas I confirmed a coat of arms for the Vilna Governorate that closely resembled the historical one.[2] A notable change was the replacement of the Double-Cross of the Jagiellonians with the Patriarchal cross on the knight's shield.[2][141]

- Coats of arms of Imperial Russian Governorates and cities, which were based on the Lithuanian coats of arms

-

Coat of arms of Cherikov from 1781

-

Coat of arms of Gorodok from 1781

-

Coat of arms of Lutsin from 1781

-

Coat of arms of Mogilev from 1781

-

Coat of arms ofRezhitsafrom 1781

-

Coat of arms ofSurazhfrom 1781

-

Coat of arms ofDrissafrom 1781

-

Coat of arms of Vitebsk from 1781

-

Coat of arms of Grodno Governorate, 1802

-

Coat of arms of Belostok Oblast, 1809

-

Coat of arms ofDünaburg, 1843

-

Coat of arms of Vilna Governorate, 1845

-

Coat of arms of Lida, 1845

-

Coat of arms of Trakai, 1846

-

Coat of arms of Vitebsk Governorate, 1856

-

Orthodox cross, 1859

-

Coat of arms of Vilna Governorate, 1878

In 1905, the

is depicted in between the flags.1915–1918

The discussions on the national flag resumed during

For the first time, according to Petras Klimas, a specific question of the national flag and national colors was raised at the Lithuanian intelligentsia Consortium Meeting of 6 June 1917 in the premises of the Lithuanian Scientific Society (the so-called Consortium Meeting united Lithuanian intellectuals in Vilnius, such as, Jonas Basanavičius, Povilas Dogelis, Petras Klimas, Jurgis Šaulys, Antanas Smetona, Mykolas Biržiška, Augustinas Janulaitis, Steponas Kairys, Aleksandras Stulginskis, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius).[143] During this Consortium Meeting, Jonas Basanavičius read a report in which he proved that in the past the color of the Lithuanian flag was red and that on the red bottom was depicted a rider with a raised sword on a dapple-grey horse.[143] Jonas Basanavičius suggested continuing this tradition and choosing this option as the flag of the reborn Lithuanian state.[143] There was nobody who opposed it, however considerations began that such variant of the national flag does not solve the issue of the national colors, especially because a red flag without Vytis (Pogonia) could not be used.[143]

As a result, new colors had to be chosen that could form a simple, everyday, easily sewn flag, which would be used alongside the historical flag of Vytis (Waykimas).

During the preparation of the Vilnius Conference, which met in Vilnius and set out the guidelines for the On 16 February 1918, the Council of Lithuania declared the Independence of Lithuania and adopted Vytis as its coat of arms with the first drafts of the coat of arms being designed by Tadas Daugirdas and Antanas Žmuidzinavičius.[49][144] On 19 April 1918, the commission accepted a Lithuanian flag project which consisted of three equal width horizontal lines of yellow, green, and red colors.[143] On 25 April 1918, the Council of Lithuania unanimously approved this flag project as the Flag of the State of Lithuania.[143] At the meeting of the same day, it was proposed to raise the tricolor flag of the Lithuanian state above the Tower of the Gediminas' Castle, which was done in the middle of 1918 after difficult negotiations with the German authorities.[143]

Following the occupation of Vilnius by

Republic of Lithuania in the interwar period

"What is the ideal of our nation? It is inscribed on the symbol of our state, inherited from the ancient times. Other nations have lions, Ares, or other symbols of power in their flags. It is beautiful, it is majestic! We have Vytis, an armored horseman on a horse with a sword in his hand, rushing with gallops. It is beautiful, it is noble! He, as published in the ancient writings, was chanted by the Vaidilas [ a clergymen in the Baltic religion ], sung by the singers. That symbol is the pride of our nation: a symbol of chivalrous justice. Let us never forget him, either in our relations with our minorities or with other states. Until we are faithful to him, no one will defeat us. The knight is righteous, but he is equipped with armors and has a sword in his hand. When necessary, he pulls out the sword and stands up for justice against those who despise it. To depict justice in this way is to feel and act not only statesmanlike, but also nationally."

— Antanas Smetona, the first and last President of interbellum Lithuania (1919–1920, 1926–1940) about the coat of arms of Lithuania.[145][146]

When Lithuania restored its independence in 1918–1920, several artists produced updated versions of the coat of arms. Almost all included a scabbard, which is not found in its earliest historical versions. A romanticized version by Antanas Žemaitis became the most popular.[2] The horse appeared to be flying through the air (courant). The gear was very ornate. For example, the saddle blanket was very long and divided into three parts.[2] There was no uniform or official version of the coat of arms. To address popular complaints, in 1929 a special commission was set up to analyze the best 16th-century specimens of Vytis to design an official state emblem.[49] Mstislav Dobuzhinsky was the chief artist.[49] The commission worked for 5 years, but its version was never officially confirmed.[49] Meanwhile, a design by Juozas Zikaras was introduced for official use on Lithuanian coins.[2]

The Columns of the Gediminids and the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians were particularly widely used in the first half of the 20th century following the restoration of the independent state of Lithuania on 16 February 1918.[23][24] These symbols, as a distinctive sign, were adopted by the Lithuanian Land Forces, Lithuanian Air Force, and other public authorities.[23][24] It was used to decorate Lithuanian coins, banknotes orders, medals, and insignias and became an attribute of numerous public societies and organizations.[23][24] To commemorate the 500th anniversary of the death of Grand Duke Vytautas the Great, flags decorated with the Columns of the Gediminids were hoisted in Lithuanian cities and towns in 1930.[23] Moreover, in his honor, a Lithuanian state award was instituted in the same year – Order of Vytautas the Great, which was awarded for distinguished services to the State of Lithuania and since 1991 is still conferred nowadays.[147]

In 1919, the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians was named the Cross for Homeland and was featured on one of the highest-ranking Lithuanian state decorations – Order of the Cross of Vytis, which was awarded for acts of bravery performed in defending the freedom and independence of Lithuania (the order was abolished following the occupations of Lithuania, but was re-established in 1991).[24][148] According to a presidential decree of 3 February 1920, issued by the President of Lithuania Antanas Smetona, the Cross for Homeland was renamed to the Cross of Vytis.[24] In 1928, the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas was instituted and was awarded to the citizens of Lithuania for outstanding performance in civil and public offices (it was also abolished following the occupations of Lithuania, but was re-established in 1991).[149]

Vytis was the state emblem of the Republic of Lithuania until 1940 when the Republic was occupied by the Soviet Union and national symbols were suppressed, those who still displayed them received severe punishments.[23] With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Vytis, together with the Columns of Gediminas and the national flag, became symbols of the independence movement in Lithuania.[23][150] In 1988, Lithuania's Soviet authorities legalized the public display of Vytis (Waykimas).[151]

- Coats of arms of the Republic of Lithuania in the interwar period

-

An unknown version of the First Lithuanian Republic coat-of-arms, probably its greater coat of arms

-

Swiss postcard with Vytis (Waykimas) and presumed territory of Lithuania, 1920.

-

Coat of arms of the Republic of Lithuania in 1921

-

Juozas Zikaras' design (1925), widely used on the interwar independent Lithuania coins

-

A banknote of 10Columns of the Gediminids(1927)

-

A banknote of 5 Lithuanian litas withVytautas the Greatand Vytis, 1929

-

A foreign passport of the Republic of Lithuania with Vytis, used until the 1940 annexation

-

A fireplace of a sitting-room of Vytautas the Great at the Kaunas Garrison Officers' Club Building

-

Transitional prize with Vytis (Waykimas) of the commander of the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union team for shooting from automatic pistols.

-

Tilsit, decorated with Vytis in 1937

-

Ministry of Finance of Lithuania Building in Kaunas, decorated with portraits of Antanas Smetona, Vytautas the Great, Vytis and the Columns of Gediminas, 1930

-

Commander of theLithuanian Army Stasys Raštikisholds the Lithuanian Army flag with Vytis on obverse side, while a Lithuanian soldier swears his loyalty by kneeling in front of it

-

A Lithuanian bomber-reconnaissance monoplane ANBO VIII with the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians, constructed by the Lithuanian aeronautical engineer Antanas Gustaitis, in 1939

-

LithuanianVickers Light Tanks M1936 with the Columns of the Gediminids, heading to the Lithuanian capital Vilniusin 1939

-

Session of the Provisional Government of Lithuania, which attempted to restore the statehood of the interwar Republic during the June Uprising in Lithuania, in 1941

-

The Lithuanian partisans fought with the occupants in 1944–1953, wearing the interwar Lithuanian uniforms and insignia

Republic of Lithuania in the post-Cold War era

On March 11, 1990, Lithuania

On September 4, 1991, a new design by

The coats of arms of Lithuania are widely used by the Lithuanian Armed Forces on uniforms, badges, and flags.[155]

In 2004, Lithuania's Seimas confirmed a new variant of the Vytis on the historical flag of Lithuania, the final design was approved on 17 June 2010.[115][156] It is depicted on a rectangular red fabric, recalling the old battle flags of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[115] The flag does not replace the yellow-green-red tri-color national flag of Lithuania and it is used on special occasions, anniversaries, and buildings of historical significance (e.g. Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, Trakai Island Castle, Medininkai Castle).[115]

It is currently proposed that a greater version of the coat of arms be adopted. It would feature a line from "Tautiška giesmė", the national anthem of Lithuania, "Vienybė težydi" ("May unity blossom"). The Seimas already uses a larger version of the coat of arms with this phrase as its motto, along with two supporters: the dexter one a griffin argent beaked and membered or, langued gules, and the sinister one a unicorn argent, armed and unguled or, langued gules, and the ducal hat on top of the shield.

The President of Lithuania uses the circular seal and document forms with the coat of arms of Lithuania, the seal has a text "Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidentas".[157]

Lithuania joined the Eurozone by adopting the euro on 1 January 2015.[158] The designs of Lithuanian euro coins share a similar national side for all denominations, featuring the Vytis and the country's name in Lithuanian – Lietuva.[154] The design was announced on 11 November 2004 following a public opinion poll conducted by the Bank of Lithuania.[159] The horse is again leaping forward, as in more traditional versions.[154]

The

Gintautas Genys released a three-tomes historical adventure novel book Pagaunės medžioklė (English: The Hunt for Pagaunė), which analyzes different periods of the history of Lithuania: the first tome, released in 2012, is about the last decade of the 18th century (close to the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth),[160] the second tome, released in 2014, presents the vision of the restoration of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the sticky web of intrigues and conflicts of the monarchs of France, Russia, and Prussia,[161] while the third tome, released in 2019, presents the course of the history of Russia, Poland, and Lithuania from the 1810s to 1860s, consistently and vividly reveals the terrible drama of mutual relations between them.[162]

In 2023, Lithuanian vehicle registration plates design was modified to include Vytis.[163]

- Coats of arms of the Republic of Lithuania in the Post-Cold War era

-

AnColumns of the Gediminidsare hanging above the stage.

-

The presidential version of the coat of arms, as depicted on the Presidential Palace, and the flag of the president of Lithuania

-

Main gates of the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania with the front portal featuring Vytis in Vilnius

-

Modern Lithuanian state flag flying at Trakai

-

The current passport of the Republic of Lithuania design

-

Litas commemorative coinfeaturing a historical Vytis

-

A banknote of 500 Lithuanian litas with Vytis, 2000

-

A coin of 1 Lithuanian Euro with Vytis, used since 1 January 2015

-

Flag of the Lithuanian Armed Forces with Vytis

-

The Lithuanian soldiers with the Columns of Gediminas during the Battle of Grunwald reconstruction

-

An armoured fighting vehicle Vilkas (Lithuanian variant of Boxer) with the Columns of the Gediminids

-

Jagielloniansin 2016

-

Jotvingis (N42) of the Lithuanian Naval Force flying the state flag at jackstaff

-

Boundary marker of the Lithuanian Republic

Related and similar coats of arms

Lithuania

Recently adopted coats of arms of Vilnius and Panevėžys counties use different color schemes and add additional details to the basic image of the knight.[164] Several towns in Lithuania use motifs similar to Vytis. For example, the coat of arms of Liudvinavas is parted per pale. One half depicts the Vytis and the other, Lady Justice.[165]

- Coats of arms of the Lithuanian counties, cities, and towns and other which features a horseman

-

Ethnographic region Aukštaitija coat of arms

-

Vilnius University coat of arms

-

Vilnius County coat of arms

-

Liudvinavas coat of arms

-

Panevėžys County coat of arms

-

Veiviržėnai coat of arms

-

Josvainiai coat of arms

-

Marijampolė coat of arms

-

Daugailiai coat of arms

-

Adutiškis coat of arms

Poland

As Lithuania and Poland were closely related for centuries, especially during the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth period, the Lithuanian coat of arms was also depicted in Poland.[130]

- Usage of Vytis (Pogonia) in Poland

-

Malbork Castle, Malbork, 1590s

-

Vytis (Pogonia) as depicted on the façade of the Collegium Novum of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków

-

Illustration with coat of arms of John I Albert (after 1492)

-

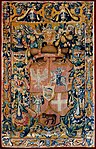

Above-door tapestry with the coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the background of a landscape with a hyena and a monkey, circa 1560, Wawel Castle

-

Choir balcony with arms of Sigismund III Vasa in the St. John's Archcathedral in Warsaw

-

Guardhouse, Poznań, 1780s

-

Podlaskie Voivodeship coat of arms

-

Brańsk coat of arms

-

Biała County (Lublin Voivodeship) coat of arms

-

Siemiatycze County coat of arms

-

Puławy County coat of arms

-

Byalistokcoat of arms

-

Siedlce coat of arms (also see: MKP Pogoń Siedlce logo)

Belarus

The Belarusian lands had been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania since the Middle Ages, so the Lithuanian coat of arms grew into the local heraldic tradition and was used in the coats of arms of Belarusian towns and administrative districts, even during Russian rule.[166] Thus, Belarusian nationalists who claimed that the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was part of a Belarusian statehood tradition adopted Lithuania's coat of arms as the Belarusian national emblem during the period of national revival in 1918.[167][168] Pahonia (Пагоня, lit. 'the chase') is the Belarusian version of the coat of arms of Lithuania, also depicting an armed white horseman on a red background.[169] However, in the Belarusian version, the two-barred cross depicted on the horseman's shild has uneven bars, the saddle blanket is in the Renaissance style, the horse's tail points down instead of up, and azure is absent from it altogether.[170]

Pahonia was chosen by the founders of the short-lived Belarusian People's Republic as the state emblem.[171] During 1918 to 1923, it was used by the military units of the Belarusian People's Republic, as well as those formed within the Lithuanian and Polish armies. Subsequently, it was used in this role by Belarusians residing in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and other countries in the interwar period.

During the Second World War, under German occupation Belarusians displayed Pahonia, it was used by collaborationist organisation, such as Belarusian People's Self-Help (BNS). They were also used by the Belarusian Central Council.[172] During the Soviet period, the Pahonia coat of arms was banned and its possession was punishable by imprisonment. Soviet propaganda defamed Belarusian national symbols as being used by "Nazi collaborators". However, the coat of arms was used freely by Belarusian organisations in the West.[173]

The white–red–white flag and Pahonia were yet again adopted upon proclaiming of Belarus' independence in 1991.

- Usage of Vytis (Pahonia) in Belarus

-

The Pahonia as used in theBelarusian People's Republicin 1918

-

Passport of the Belarusian People's Republic, 1918–1919

-

Seal of theByelorussian Central Council in 1943–1944 (during the period of the Nazi occupation)

-

Marshal's insignia of theByelorussian Home Defence, 1944–1945

-

Coat of arms of Belarus from 1991 to 1995

-

Coat of arms ofVitsebsk Region

-

Coat of arms of Lyepyel

-

Coat of arms ofVierchniadzvinsk

-

Coat of arms of Rechytsa

-

Coat of arms ofMahilyow

-

Coat of arms of Lipnishki

-

Belarusian opposition supporters holding flags with Pahonia during the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests

-

Belarusian opposition supporters holding Pahonia signs during the protests against the Russian invasion of Ukraine

Ukraine

The horseman was featured on the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, on the Seal of King Yuri II Boleslav with the Ruthenian lion on the coat of arms, on the Mykhailo Hrushevsky's proposal of the coat of arms of the Ukrainian People's Republic, and other Ukrainian coats of arms.

- Coats of arms in Ukraine which features a horseman

-

Coats of arms of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, 1313

-

Seal of King Yuri II Boleslav denoting a horseman with lion on the coat of arms (14th century)

-

King Yuri II Boleslav's coin of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia (14th century)

-

Coat of arms with Vytis (Waykimas) of Švitrigaila, circa 1440, who at the time ruled Ruthenian territories in Ukraine[178]

-

Coat of arms of Iziaslav, Ukraine, since 1754[179]

-

Watch tower ofVytautas the Great in Kherson Oblastwith the historical state flag of Lithuania

-

The coat of arms of Dukes Czartoryski with Vytis above the portal of the former Dominican Church in Chernelytsia

-

Mykhailo Hrushevskyi's proposal for the coat of arms of the Ukrainian People's Republic

-

Coat of arms ofKolkyunder Polish rule

-

Coat of arms of Zhytomyr Oblast

-

Coat of arms of Staryi Chortoryisk

-

Coat of arms of Nemenka

-

Coat of arms of Lytovezh

-

Coat of arms of Starokostiantyniv Raion in 2004–2020

-

Coat of arms of Vitovka Raion in 2017–2020

-

Collar of the president of Ukraine, one of whose medallions contains Vytis (Pohonia)

Russia

Due to historical connections with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (and later Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth), some Russian regions adopted Lithuanian coat of arms from the Russian Empire period. After the dissolution of the USSR, such coats of arms were restored.

- Usage of Vytis (Pogonya) in Russia

-

Coat of arms of Sebezh

-

Coat of arms of Nevel

-

Coat of arms of Velizh

-

The Lithuanian coat of arms on display at the Smolensk Historical museum

Noble families

| Pogoń Litewska | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name(s) | Pogoń Litewska Książęca |

| Families | 57 names Aczkiewicz, Algiminowicz, Algminowicz, Alkimowicz, Trubecki, Wandza, Worotyniec , Zasławski

|

| Cities | Chowanski,[182] Trubetskoy[183] and Golitsyn.[184] In Polish heraldry, those coat of arms are called Pogoń Litewska.[185]

Other locationsAustria

France

Latvia

Sweden

Germany

United States

See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to National coats of arms of Lithuania. References

Bibliography

Articles

Books

|

![Lithuanian Vytis (Waykimas) on Tenebrat Bell (which was possibly funded by Jogaila in circa 1388) of St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków[108]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Coat_of_arms_of_Lithuania_Vytis_%28Waykimas%29%2C_depicted_on_Tenebrat_Bell_%28which_was_possibly_funded_by_Jogaila_and_Jadwiga_in_circa_1388%29_of_St._Mary%27s_Basilica_in_Krak%C3%B3w%2C_Poland.jpg/132px-thumbnail.jpg)

![One of the earliest surviving depictions of Vytis (Waykimas) in a flag of Vytautas the Great. Painted in 1416 by a Portuguese herald, who attended the Council of Constance.[114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Flag_of_Vytautas_the_Great_with_a_standing_knight_of_K%C4%99stutai%C4%8Diai_and_Lithuanian_Vytis_%28Waikymas%29%2C_used_during_the_Council_of_Constance_in_1416.jpg/50px-Flag_of_Vytautas_the_Great_with_a_standing_knight_of_K%C4%99stutai%C4%8Diai_and_Lithuanian_Vytis_%28Waikymas%29%2C_used_during_the_Council_of_Constance_in_1416.jpg)

![Lithuanian coat of arms, dating to 1475, which, judging from its archaic look, was likely redrawn from an even earlier painting[114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ae/Lithuanian_Vytis_%28Waykimas%29_from_the_Bavarian_State_Library_%281475%29.jpg/86px-Lithuanian_Vytis_%28Waykimas%29_from_the_Bavarian_State_Library_%281475%29.jpg)

![Insignia of the Life-Guards Lithuanian Regiment [ru]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Insignia_of_the_Lithuanian_Regiment_of_the_Imperial_Guard_of_the_Russian_Empire_with_Vytis_%28Waykimas%29%2C_1910.jpg/150px-Insignia_of_the_Lithuanian_Regiment_of_the_Imperial_Guard_of_the_Russian_Empire_with_Vytis_%28Waykimas%29%2C_1910.jpg)

![Coat of arms of Lipnishki [be]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/BIA_Lipniszki_COA.png/123px-BIA_Lipniszki_COA.png)

![Coat of arms with Vytis (Waykimas) of Švitrigaila, circa 1440, who at the time ruled Ruthenian territories in Ukraine[178]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Pahonia._%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%8F_%281440%29.jpg/92px-Pahonia._%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%8F_%281440%29.jpg)

![Coat of arms of Iziaslav, Ukraine, since 1754[179]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/Coat_of_arms_of_Iziaslav.png/125px-Coat_of_arms_of_Iziaslav.png)

![Coat of arms of Nemenka [uk]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2f/Coat_of_arms_of_Nemenka_%28Vinnytsia_Raion%29.svg/110px-Coat_of_arms_of_Nemenka_%28Vinnytsia_Raion%29.svg.png)