User:Irtapil/Phoenician alphabet

Phoenician alphabet

pre-deletion version of Phoenician alphabet

intro

| Phoenician alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Script type | ||

Time period | c. 1200–150 BC Unicode range U+10900–U+1091F | |

| History of the alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

The Phoenician alphabet, called by convention the Proto-Canaanite alphabet for inscriptions older than around 1050 BC, is the oldest verified

The Phoenician alphabet, which the Phoenicians adapted from the early West Semitic alphabet,

As the letters were originally incised with a

Phoenician was usually written right to left, though some texts alternate directions (boustrophedon).

History

Origin

The earliest known alphabetic (or "proto-alphabetic") inscriptions are the so-called

The Phoenician alphabet is a direct continuation of the "Proto-Canaanite" script of the

Spread of the alphabet and its social effects

Beginning in the 9th century BC, adaptations of the Phoenician alphabet thrived, including

Another reason for its success was the

The alphabet had long-term effects on the social structures of the civilizations that came in contact with it. Its simplicity not only allowed its easy adaptation to multiple languages, but it also allowed the common people to learn how to write. This upset the long-standing status of literacy as an exclusive achievement of royal and religious elites,

Modern rediscovery

The Phoenician alphabet was first uncovered in the 17th century, but up to the 19th century its origin was unknown. It was at first believed that the script was a direct variation of

The Phoenician alphabet was known by the

Development

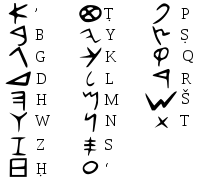

The Phoenician letter forms shown here are idealized: actual Phoenician writing was cruder and less uniform, with significant variations by era and region.

When alphabetic writing began in

The chart shows the graphical evolution of Phoenician letter forms into other alphabets. The sound values also changed significantly, both at the initial creation of new alphabets and from gradual pronunciation changes which did not immediately lead to spelling changes.[18]

| Letter | Name[19] | Possible Meaning | Phoneme | Origin | Corresponding letter in | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Aramaic | Syriac/ Assyrian | Hebrew | Arabic | Maledivan Thaana | South Arabian

|

Ethiopian Ge'ez

|

Greek | Egyptian Coptic

|

Anatolian Lydian | Old Italic

|

Germanic Runes | Latin | Slavic Cyrillic | Georgian | Armenian

|

Old Turkic

|

Mongolian | Tibetan

|

Indic Devanagari | Bengali | Burmese | Sinhala | Khmer

|

Thai

|

Lao

|

Javanese | ||||

| 𐤀 | ʾalp | ox | ʾ [ʔ] | 𓃾 | 𐡀 | ܐ | א | ﺍ | އ | 𐩱 | አ | Α α

|

Ⲁⲁ | 𐤠 | 𐌀 | ᚨ | Aa | А а

|

ა/ⴀ/Ⴀ | Ա/ա | 𐰀 | ཨ | अ , आ, ओ, औ, अं, अः, ॲ, ऑ

|

অ, আ, ও, ঔ | အ | ꦨ, ආ, ඇ, ඈ | អ | อ | ອ | ꦄ | ||

| 𐤁 | bēt | house, cow | b [b] | 𓉐 | 𐡁 | ܒ | ב | ﺏ | ބ | 𐩨 | በ | Β β

|

Ⲃⲃ | 𐤡 | 𐌁 | ᛒ | Bb | В в

|

ბ/ⴁ/Ⴁ | Բ/բ | 𐰉 | བ, མ | ब , भ

|

ব, ভ | ဗ, ဘ | බ, භ | ប, ផ | บ | ບ | ꦧ, ꦨ | ||

| 𐤂 | gimel | throwing stick, camel, calf, drink | g [ɡ] | 𓌙 | 𐡂 | ܓ | ג | ﺝ | ޖ ,ޗ | 𐩴 | ገ | Γ γ

|

Ⲅⲅ | 𐤢 | 𐌂 | ᚷ, ᛃ | Cc, Gg | Ґ ґ

|

გ/ⴂ/Ⴂ | Գ/գ | 𐰍 | ག | ग | গ | ဂ | ග | គ | ค, ฅ | ຄ | ꦒ | ||

| 𐤃 | dalt | door, udder, bucket | d [ d ]

|

𓇯 | 𐡃 | ܕ | ד | د, ذ | ޑ, ޛ | 𐩵 | ደ | Δ δ

|

Ⲇⲇ | 𐤣 | 𐌃 | ᛞ | Dd | Д д

|

დ/ⴃ/Ⴃ | Դ/դ | 𐰑 | – | ད | ध | গ | ဒ | ධ | ឌ | ฎ | ດ | ꦣ | |

| 𐤄 | hē | window, feather, pen | h [h] | 𓀠 | 𐡄 | ܗ | ה | ه | ހ | 𐩠 | ሀ | Ε ε

|

Ⲉⲉ | 𐤤 | 𐌄 | ᛖ | Ee | Э э

|

ე/ⴄ/Ⴄ | Ե/ե, Է/է, Ը/ը | – | – | – | ह | এ | ဧ | එ | ហ | ห | ຫ | ꦌ, ꦍ | |

| 𐤅 | wāw | hook, hoe | w [w] | 𓏲 | 𐡅 | ܘ | ו | ﻭ | ވ, ޥ | 𐩥 | ወ | ( Υ υ

|

Ⲩⲩ | 𐤥,𐤱,𐤰 | 𐌅, 𐌖 | ᚹ | Ff, Uu, Vv, Yy, Ww | ( Ў ў

|

ვ/ⴅ/Ⴅ | Վ/վ | – | ཝ | ह | ব | ဝ | ව | វ | ว | ວ | ꦮ | ||

| 𐤆 | zēn | weapon, plough, grain-wagon | z [d͡z] | 𓏭 | 𐡆 | ܙ | ז | ﺯ | ޒ, ޜ | 𐩹 | ዘ | Ζ ζ

|

Ⲍⲍ | – | 𐌆 | ᛉ | Zz | З з

|

ზ/ⴆ/Ⴆ | Զ/զ | 𐰔 | ཇ, ཛ, ཛྷ | ज, झ | জ, ঝ | ဇ, ဈ | ජ, ඣ | ជ | ช, ซ | ຊ | ꦗ, ꦙ | ||

| 𐤇 | ḥēt | wall, courtyard | ḥ [x] | 𓉗 or 𓈈 | 𐡇 | ܚ | ח | ح, خ | ޙ, ޚ | 𐩢, 𐩭 | ኀ

|

Η η

|

Ⲏⲏ | – | 𐌇 | ᚺ/ᚻ | Hh | Й й

|

ი /ⴈ/Ⴈ

|

Ի/ի, Խ/խ | – | གྷ | घ | ঘ | ဃ | ඝ | ឃ | ฆ | – | ꦓ | ||

| 𐤈 | ṭēt | wheel | ṭ [ t ]

|

𓄤 | 𐡈 | ܛ | ט | ط, ظ | ޘ, ދ | 𐩷 | ጠ | Θ θ

|

Ⲑⲑ | – | 𐌈 | ᚦ | Þþ [citation needed] | ( Ѳ ѳ)

|

თ/ⴇ/Ⴇ | Թ/թ | 𐰦 | – | ཐ | थ, ठ, ट | ট | ဈ | ඣ | ដ | ฏ | – | ꦛ | |

| 𐤉 | yad | hand, shovel, handle | y [j] | 𓂝 | 𐡉 | ܝ | י | ي | ޔ | 𐩺 | የ | Ι ι

|

Ⲓⲓ | 𐤦 | 𐌉 | ᛁ | Ii, Jj | Ј ј

|

ჲ | Յ/յ | 𐰖 | ཡ | य | য | ယ, ရ | ය | យ | ย | ຢ | ꦪ | ||

| 𐤊 | kap | palm of a hand, dustpan | k [k] | 𓂧 | 𐡊 | ܟ | כך | ﻙ | ކ | 𐩫 | ከ | Κ κ

|

Ⲕⲕ | 𐤨 | 𐌊 | ᚲ | Kk | К к

|

კ/ⴉ/Ⴉ | Կ/կ | 𐰚 | ཀ | क | ক | က | ක | ក | ก | ກ | ꦏ | ||

| 𐤋 | lamed | goad | l [ l ]

|

𓌅 | 𐡋 | ܠ | ל | ﻝ | ލ, ޅ | 𐩡 | ለ | Λ λ

|

Ⲗⲗ | 𐤩 | 𐌋 | ᛚ | Ll | Л л

|

ლ/ⴊ/Ⴊ | Լ/լ | 𐰞 | ལ | ल | ল | လ, ဠ | ළ | ល | ล | ລ | ꦭ | ||

| 𐤌 | mēm | water | m [m] | 𓈖 | 𐡌 | ܡ | מם | ﻡ | މ | 𐩣 | መ | Μ μ

|

Ⲙⲙ | 𐤪 | 𐌌 | ᛗ | Mm | М м

|

მ/ⴋ/Ⴋ | Մ/մ | 𐰢 | མ | म | ম | မ | ම | ម | ม | ມ | ꦩ | ||

| 𐤍 | nūn | fish, serpent | n [ n ]

|

𓆓 | 𐡍 | ܢ | נן | ﻥ | ނ, ޏ | 𐩬 | ነ | Ν ν

|

Ⲛⲛ | 𐤫 | 𐌍 | ᚾ | Nn | Н н

|

ნ/ⴌ/Ⴌ | Ն/ն | 𐰣 | ང, ཉ, ན | न, ण, ञ, ङ | ঙ, ঞ, ণ, ন | င, ဉ, ည, ဏ, န | ඞ, ඤ, ණ, න | ង, ញ, ណ | ง, ณ, น | ງ, ຍ, ນ | ꦔ, ꦚ, ꦟ, ꦤ | ||

| 𐤎 | sāmek | fishbone, fish, djed | s [s] | 𓊽 | 𐡎 | ܣ, ܤ | ס | س | — | 𐩪 | ሰ | Χ χ

|

Ⲝⲝ, Ⲭⲭ | – | 𐌎, 𐌗 | ᛊ,ᛋ

|

Xx | ( Х х

|

ს/ⴑ/Ⴑ | Ս/ս | 𐰽 | – | ས | ष, स | ষ, স | သ | ස | ស, ឞ | ส, ษ | ສ, ຊ | ꦯ, ꦰ | |

| 𐤏 | ʿēn | eye, water-spring | ʿ [ʕ] | 𓁹 | 𐡏 | ܥ | ע | غ

|

ޣ

|

𐩲 | ዐ | Ω ω

|

Ⲟⲟ, Ⲱⲱ | 𐤬 | 𐌏 | ᛟ

|

Oo | О о

|

ო/ⴍ/Ⴍ | Օ/օ | 𐰆 | – | ए, ऐ | এ,ঐ | ဩ, ဪ | ඔ | អុ | – | – | ꦎ, ꦎꦴ | ||

| 𐤐 | pē | mouth, well | p [p] | 𓂋 | 𐡐 | ܦ | פף | ف | ފ, ޕ | 𐩰 | ፐ, ፈ | Ππ | Ⲡⲡ | – | 𐌐 | ᛈ | Pp | П п

|

პ/ⴎ/Ⴎ | Պ/պ | 𐰯 | – | པ, ཕ | प, फ | প, ফ | ပ, ဖ | ප, ඵ | ព, ភ | ป | ປ, ຜ | ꦥ, ꦦ | |

| 𐤑 | ṣade | plant/sapling, fishnet, fishing hook | ṣ [t͡s] | 𓇑 | 𐡑 | ܨ | צץ | ص, ض | ޞ, ޟ | 𐩮 | ጸ, ጰ, ፀ | ( Ϻ ϻ)

|

– | — | 𐌑 | — | – | Џ џ

|

ც/ⴚ/Ⴚ | Ց/ց | – | ཅ, ཆ, ཙ, ཚ | च, छ | চ, ছ | စ, ဆ | ච, ඡ | ច, ឆ | จ, ฉ | ຈ | ꦕ, ꦖ | ||

| 𐤒 | qūp | needle eye | q [q] | 𓃻 | 𐡒 | ܩ | ק | ﻕ | ޤ, ގ | 𐩤 | ቀ | ( Ψ ψ

|

Ϥϥ, Ⲫⲫ, Ⲯⲯ | – | 𐌒, 𐌘, 𐌙 | – | ( Ф ф)

|

ქ/ⴕ/Ⴕ | Ք/ք, Փ/փ, Ֆ/ֆ | 𐰴 | – | ཁ | ख

|

খ | ခ | ඛ | ខ | ข, ฃ | ຂ | ꦑ | ||

| 𐤓 | rūš | head, harpoon | r [ r ]

|

𓁶 | 𐡓 | ܪ | ר | ﺭ | ރ | 𐩧 | ረ | Ρ ρ

|

Ⲣⲣ | 𐤭 | 𐌓 | ᚱ | Rr | Р р

|

რ/ⴐ/Ⴐ | Ր/ր | 𐰺 | ར | र | র | – | ර | រ | ร | ຣ | ꦫ | ||

| 𐤔 | šīn | tooth, toothed knife | š [ʃ] | 𓌓 | 𐡔 | ܫ | ש | ش, س | ޝ, ސ | 𐩦 | ሠ | Σσς | Ⲋⲋ, Ⲥⲥ, Ϣϣ | 𐤮 | 𐌔 | ᛊ/ᛋ

|

Ss | Щ щ

|

შ/ⴘ/Ⴘ | Շ/շ | 𐱁 | ཤ | श | শ | – | – | ឝ | ศ | – | ꦯ | ||

| 𐤕 | tāw | mark | t [θ] | 𓏴 | 𐡕 | ܬ | ת | ت, ث | ތ, ޘ | 𐩩 | ተ | Τ τ

|

Ⲋⲋ, Ⲧⲧ | 𐤯 | 𐌕 | ᛏ | Tt | Т т

|

ტ/ⴒ/ | Տ/տ | 𐱃 | ཏ | त | ত | တ | ත | ត | ต, ด | ຕ | ꦠ | ||

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain | Emphatic | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | k | q | ʔ | ||||

| Voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||||||

| Affricate | Voiceless | t͡s | ||||||||

| Voiced | d͡z | |||||||||

| Fricative | Voiceless | θ | s | ʃ | x | h | ||||

| Voiced | ʕ | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||

Letter names

Phoenician used a system of acrophony to name letters: a word was chosen with each initial consonant sound, and became the name of the letter for that sound. These names were not arbitrary: each Phoenician letter was based on an Egyptian hieroglyph representing an Egyptian word; this word was translated into Phoenician (or a closely related Semitic language), then the initial sound of the translated word became the letter's Phoenician value.[20] For example, the second letter of the Phoenician alphabet was based on the Egyptian hieroglyph for "house" (a sketch of a house); the Semitic word for "house" was bet; hence the Phoenician letter was called bet and had the sound value b.

According to a 1904 theory by Theodor Nöldeke, some of the letter names were changed in Phoenician from the Proto-Canaanite script.[dubious ] This includes:

- gaml "throwing stick" to gimel "camel"

- digg "fish" to dalet "door"

- hll "jubilation" to he "window"

- ziqq "manacle" to zayin "weapon"

- naḥš "snake" to nun "fish"

- piʾt "corner" to pe "mouth"

- šimš "sun" to šin "tooth"

Yigael Yadin (1963) went to great lengths to prove that there was actual battle equipment similar to some of the original letter forms.[21]

Numerals

The Phoenician numeral system consisted of separate symbols for 1, 10, 20, and 100. The sign for 1 was a simple vertical stroke (𐤖). Other numbers up to 9 were formed by adding the appropriate number of such strokes, arranged in groups of three. The symbol for 10 was a horizontal line or tack (𐤗). The sign for 20 (𐤘) could come in different glyph variants, one of them being a combination of two 10-tacks, approximately Z-shaped. Larger multiples of ten were formed by grouping the appropriate number of 20s and 10s. There existed several glyph variants for 100 (𐤙). The 100 symbol could be multiplied by a preceding numeral, e.g. the combination of "4" and "100" yielded 400.

Unicode

| Phoenician | |

|---|---|

| Range | U+10900..U+1091F (32 code points) |

| Plane | SMP |

| Scripts | Phoenician |

| Assigned | 29 code points |

| Unused | 3 reserved code points |

| Unicode version history | |

| 5.0 (2006) | 27 (+27) |

| 5.2 (2009) | 29 (+2) |

| Unicode documentation | |

| Code chart ∣ Web page | |

| Note: [24][25] | |

The Phoenician alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in July 2006 with the release of version 5.0. An alternative proposal to handle it as a font variation of Hebrew was turned down. (See PDF summary.)

The Unicode block for Phoenician is U+10900–U+1091F. It is intended for the representation of text in Palaeo-Hebrew, Archaic Phoenician, Phoenician, Early Aramaic, Late Phoenician cursive, Phoenician papyri, Siloam Hebrew, Hebrew seals, Ammonite, Moabite, and Punic.

The letters are encoded U+10900 𐤀 aleph through to U+10915 𐤕 taw, U+10916 𐤖, U+10917 𐤗, U+10918 𐤘 and U+10919 𐤙 encode the numerals 1, 10, 20 and 100 respectively and U+1091F 𐤟 is the word separator.

Block

| Phoenician[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1090x | 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 |

| U+1091x | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | 𐤖 | 𐤗 | 𐤘 | 𐤙 | 𐤚 | 𐤛 | 𐤟 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

History

The following Unicode-related documents record the purpose and process of defining specific characters in the Phoenician block:

| Version | Final code points[a] | Count | L2 ID | WG2 ID | Document |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | U+10900..10919, 1091F | 27 | N1579 | Everson, Michael (1997-05-27), Proposal for encoding the Phoenician script | |

| L2/97-288 | N1603 | Umamaheswaran, V. S. (1997-10-24), "8.24.1", Unconfirmed Meeting Minutes, WG 2 Meeting # 33, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 20 June – 4 July 1997 | |||

| L2/99-013 | N1932 | Everson, Michael (1998-11-23), Revised proposal for encoding the Phoenician script in the UCS | |||

| L2/99-224 | N2097, N2025-2 | Röllig, W. (1999-07-23), Comments on proposals for the Universal Multiple-Octed Coded Character Set | |||

| N2133 | Response to comments on the question of encoding Old Semitic scripts in the UCS (N2097), 1999-10-04 | ||||

| L2/00-010 | N2103 | Umamaheswaran, V. S. (2000-01-05), "10.4", Minutes of WG 2 meeting 37, Copenhagen, Denmark: 1999-09-13—16 | |||

| L2/04-149 | Kass, James; Anderson, Deborah W.; Snyder, Dean; Lehmann, Reinhard G.; Cowie, Paul James; Kirk, Peter; Cowan, John; Khalaf, S. George; Richmond, Bob (2004-05-25), Miscellaneous Input on Phoenician Encoding Proposal | ||||

| L2/04-141R2 | N2746R2 | Everson, Michael (2004-05-29), Final proposal for encoding the Phoenician script in the UCS | |||

| L2/04-177 | Anderson, Deborah (2004-05-31), Expert Feedback on Phoenician | ||||

| L2/04-178 | N2772 | Anderson, Deborah (2004-06-04), Additional Support for Phoenician | |||

| L2/04-181 | Keown, Elaine (2004-06-04), REBUTTAL to “Final proposal for encoding the Phoenician script in the UCS” | ||||

| L2/04-190 | N2787 | Everson, Michael (2004-06-06), Additional examples of the Phoenician script in use | |||

| L2/04-187 | McGowan, Rick (2004-06-07), Phoenician Recommendation | ||||

| L2/04-206 | N2793 | Kirk, Peter (2004-06-07), Response to the revised "Final proposal for encoding the Phoenician script" (L2/04-141R2) | |||

| L2/04-213 | Rosenne, Jony (2004-06-07), Responses to Several Hebrew Related Items | ||||

| L2/04-217R | Keown, Elaine (2004-06-07), Proposal to add Archaic Mediterranean Script block to ISO 10646 | ||||

| L2/04-226 | Durusau, Patrick (2004-06-07), Statement of the Society of Biblical Literature on WG2 N2746R2 | ||||

| L2/04-218 | N2792 | Snyder, Dean (2004-06-08), Response to the Proposal to Encode Phoenician in Unicode | |||

| L2/05-009 | N2909 | Anderson, Deborah (2005-01-19), Letters in support of Phoenician | |||

| 5.2 | U+1091A..1091B | 2 | N3353 (pdf, doc) | Umamaheswaran, V. S. (2007-10-10), "M51.14", Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 51 Hanzhou, China; 2007-04-24/27 | |

| L2/07-206 | N3284 | Everson, Michael (2007-07-25), Proposal to add two numbers for the Phoenician script | |||

| L2/07-225 | Moore, Lisa (2007-08-21), "Phoenician", UTC #112 Minutes | ||||

| |||||

Derived alphabets

Middle Eastern descendants

The

The Aramaic alphabet, used to write

The

The Arabic script is a descendant of Phoenician via Aramaic.

The

Derived European scripts

According to Herodotus,[26] the Phoenician prince Cadmus was accredited with the introduction of the Phoenician alphabet—phoinikeia grammata, "Phoenician letters"—to the Greeks, who adapted it to form their Greek alphabet, which was later introduced to the rest of Europe. Herodotus estimates that Cadmus lived sixteen hundred years before his time, or around 2000 BC, and claims that the Greeks did not know of the Phoenician alphabet before Cadmus.[27]

Modern historians agree that

The

Brahmic scripts

Many Western scholars believe that the

However, due to an indigenous-origin hypothesis of Brahmic scripts, no definitive scholarly consensus exists.

Surviving examples

- Ahiram sarcophagus

- Bodashtart

- Çineköy inscription

- Cippi of Melqart

- Eshmunazar

- Karatepe

- Kilamuwa Stela

- Nora Stone

- Pyrgi Tablets

- Temple of Eshmun

See also

- Arabic alphabet

- Aramaic alphabet

- Armenian alphabet

- Avestan alphabet

- Greek alphabet

- Hebrew alphabet

- Old Turkic script

- Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

- Paleo-Hebrew Leviticus scroll

- Tanakh at Qumran

- Tifinagh

- Ugaritic alphabet

References

- Bronze Age collapse period, classical form from about 1050 BC; gradually died out during the Hellenistic period as its evolved forms replaced it; obsolete with the destruction of Carthagein 149 BC.

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- ^ Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). A history of writing. Reaktion Books. p. 90.

- ^ "Phoenicia". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

- ^ Beyond Babel: A Handbook for Biblical Hebrew and Related Languages, article by Charles R. Krahmalkov (ed. John Kaltner, Steven L. McKenzie, 2002). "This alphabet was not, as often mistakenly asserted, invented by the Phoenicians but, rather, was an adaptation of the early West Semitic alphabet to the needs of their own language".

- ^ Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies. P. 23.

- ISBN 978-0-19-104448-9.

[...] scribes wrote in Paleo-Hebrew, a local variant of the Phoenician alphabetic script [...]

- ^ Coulmas (1989) p. 141.

- ^ Markoe (2000) p. 111

- ^ Hock and Joseph (1996) p. 85.

- ^ Daniels (1996) p. 94-95.

- ^ "Discovery of Egyptian Inscriptions Indicates an Earlier Date for Origin of the Alphabet". Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Fischer (2003) p. 68-69.

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 256.

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 256-258.

- Zevahim 62a; Sanhedrin22a, et al.)

- ^ "Charts" (PDF). unicode.org.

- OCLC 237631007.

- ^ after Fischer, Steven R. (2001). A History of Writing. London: Reaction Books. p. 126.

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 262-263.

- ^ Yigael Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands. McGraw-Hill, 1963. The Samech – a quick war ladder, later to become the '$' dollar sign drawing the three internal lines quickly. The 'Z' shaped Zayin – an ancient boomerang used for hunting. The 'H' shaped Het – mammoth tuffs.

- ^ "Phoenician numerals in Unicode], [http://www.dma.ens.fr/culturemath/histoire%20des%20maths/htm/Verdan/Verdan.htm Systèmes numéraux" (PDF). Retrieved 20 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Number Systems". Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ "Unicode character database". The Unicode Standard. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- ^ "Enumerated Versions of The Unicode Standard". The Unicode Standard. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, Book V, 58.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, Book II, 145

- ^ ISBN 9780313327636. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Spurkland, Terje (2005): Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions, translated by Betsy van der Hoek, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, pp. 3–4

- ^ Richard Salomon, "Brahmi and Kharoshthi", in The World's Writing Systems

- ISBN 9781594777943.

Sources

- ISBN 2-914266-04-9

- Maria Eugenia Aubet, The Phoenicians and the West Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, London, 2001.

- Daniels, Peter T., et al. eds. The World's Writing Systems Oxford. (1996).

- Jensen, Hans, Sign, Symbol, and Script, G.P. Putman's Sons, New York, 1969.

- Coulmas, Florian, Writing Systems of the World, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 1989.

- Hock, Hans H. and Joseph, Brian D., Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship, Mouton de Gruyter, New York, 1996.

- Fischer, Steven R., A History of Writing, Reaktion Books, 1999.

- Markoe, Glenn E., Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22613-5(2000) (hardback)

- Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic on Coins, reading and transliterating Proto-Hebrew, online edition. (Judaea Coin Archive)

External links

- Ancient Scripts.com (Phoenician)

- Omniglot.com (Phoenician alphabet)

- official Unicode standards document for Phoenician (PDF file)

- [1] Free-Libre GPL2 Licensed Unicode Phoenician Font

- GNU FreeFont Unicode font family with Phoenician range in its serif face.

- [2] Phönizisch TTF-Font.