Cancer

This article includes a improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (March 2024) ) |

| Cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | five-year survival 66% (USA)[5] |

| Frequency | 24 million annually (2019)[6] |

| Deaths | 10 million annually (2019)[6] |

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.[2][7] These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread.[7] Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bleeding, prolonged cough, unexplained weight loss, and a change in bowel movements.[1] While these symptoms may indicate cancer, they can also have other causes.[1] Over 100 types of cancers affect humans.[7]

These environmental factors act, at least partly, by changing the genes of a cell.[11] Typically, many genetic changes are required before cancer develops.[11] Approximately 5–10% of cancers are due to inherited genetic defects.[12] Cancer can be detected by certain signs and symptoms or screening tests.[2] It is then typically further investigated by medical imaging and confirmed by biopsy.[13]

The risk of developing certain cancers can be reduced by not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol intake, eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, and

In 2015, about 90.5 million people worldwide had cancer.[19] In 2019, annual cancer cases grew by 23.6 million people, and there were 10 million deaths worldwide, representing over the previous decade increases of 26% and 21%, respectively.[6][20]

The most common types of cancer in males are

Etymology and definitions

The word comes from the ancient Greek καρκίνος, meaning 'crab' and 'tumor'. Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen, among others, noted the similarity of crabs to some tumors with swollen veins. The word was introduced in English in the modern medical sense around 1600.[27]

Cancers comprise a large family of diseases that involve abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.[2][7] They form a subset of neoplasms. A neoplasm or tumor is a group of cells that have undergone unregulated growth and will often form a mass or lump, but may be distributed diffusely.[28][29]

All tumor cells show the six hallmarks of cancer. These characteristics are required to produce a malignant tumor. They include:[30]

- Cell growth and division absent the proper signals

- Continuous growth and division even given contrary signals

- Avoidance of programmed cell death

- Limitless number of cell divisions

- Promoting blood vessel construction

- Invasion of tissue and formation of metastases[30]

The progression from normal cells to cells that can form a detectable mass to cancer involves multiple steps known as malignant progression.[30][31]

Signs and symptoms

When cancer begins, it produces no symptoms. Signs and symptoms appear as the mass grows or

People may become anxious or depressed post-diagnosis. The risk of suicide in people with cancer is approximately double.[33]

Local symptoms

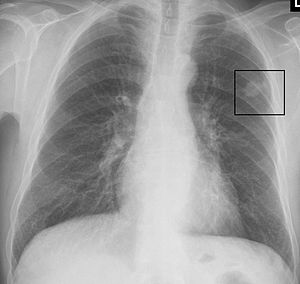

Local symptoms may occur due to the mass of the tumor or its ulceration. For example, mass effects from lung cancer can block the

Systemic symptoms

Systemic symptoms may occur due to the body's response to the cancer. This may include fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or skin changes.[34] Some cancers can cause a systemic inflammatory state that leads to ongoing muscle loss and weakness, known as cachexia.[35]

Some cancers, such as

Shortness of breath, called

Some systemic symptoms of cancer are caused by hormones or other molecules produced by the tumor, known as

Metastasis

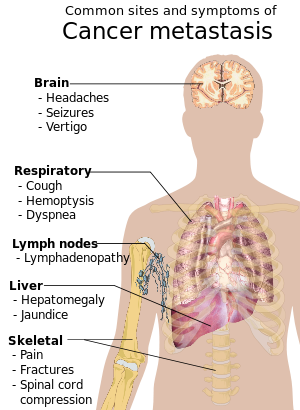

Metastasis is the spread of cancer to other locations in the body. The dispersed tumors are called metastatic tumors, while the original is called the primary tumor. Almost all cancers can metastasize.[39] Most cancer deaths are due to cancer that has metastasized.[40]

Metastasis is common in the late stages of cancer and it can occur via the blood or the lymphatic system or both. The typical steps in metastasis are local invasion, intravasation into the blood or lymph, circulation through the body, extravasation into the new tissue, proliferation and angiogenesis. Different types of cancers tend to metastasize to particular organs, but overall the most common places for metastases to occur are the lungs, liver, brain, and the bones.[39]

While some cancers can be cured if detected early, metastatic cancer is more difficult to treat and control. Nevertheless, some recent treatments are demonstrating encouraging results.[41]

Causes

The majority of cancers, some 90–95% of cases, are due to genetic mutations from environmental and lifestyle factors.

Environmental or lifestyle factors that caused cancer to develop in an individual can be identified by analyzing mutational signatures from genomic sequencing of tumor DNA. For example, this can reveal if lung cancer was caused by tobacco smoke, if skin cancer was caused by UV radiation, or if secondary cancers were caused by previous chemotherapy treatment.[47]

Cancer is generally not a

Chemicals

Exposure to particular substances have been linked to specific types of cancer. These substances are called carcinogens.

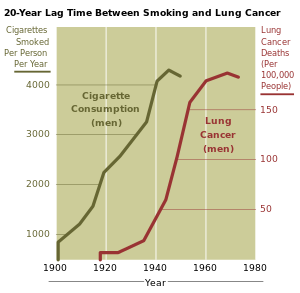

Tobacco smoke, for example, causes 90% of lung cancer.[49] Tobacco use can cause cancer throughout the body including in the mouth and throat, larynx, esophagus, stomach, bladder, kidney, cervix, colon/rectum, liver and pancreas.[50][51] Tobacco smoke contains over fifty known carcinogens, including nitrosamines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[52]

Tobacco is responsible for about one in five cancer deaths worldwide[52] and about one in three in the developed world.[53] Lung cancer death rates in the United States have mirrored smoking patterns, with increases in smoking followed by dramatic increases in lung cancer death rates and, more recently, decreases in smoking rates since the 1950s followed by decreases in lung cancer death rates in men since 1990.[54][55]

In Western Europe, 10% of cancers in males and 3% of cancers in females are attributed to alcohol exposure, especially liver and digestive tract cancers.[56] Cancer from work-related substance exposures may cause between 2 and 20% of cases,[57] causing at least 200,000 deaths.[58] Cancers such as lung cancer and mesothelioma can come from inhaling tobacco smoke or asbestos fibers, or leukemia from exposure to benzene.[58]

Exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), which is predominantly used in the production of Teflon, is known to cause two kinds of cancer.[59][60]

Chemotherapy drugs such as

Diet and exercise

Diet, physical inactivity, and obesity are related to up to 30–35% of cancer deaths.[3][61] In the United States, excess body weight is associated with the development of many types of cancer and is a factor in 14–20% of cancer deaths.[61] A UK study including data on over 5 million people showed higher body mass index to be related to at least 10 types of cancer and responsible for around 12,000 cases each year in that country.[62] Physical inactivity is believed to contribute to cancer risk, not only through its effect on body weight but also through negative effects on the immune system and endocrine system.[61] More than half of the effect from the diet is due to overnutrition (eating too much), rather than from eating too few vegetables or other healthful foods.[citation needed]

Some specific foods are linked to specific cancers. A high-salt diet is linked to

Infection

Worldwide, approximately 18% of cancer deaths are related to

- Human papillomavirus (cervical cancer),

- B-cell lymphoproliferative disease and nasopharyngeal carcinoma),

- Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (Kaposi's sarcomaand primary effusion lymphomas),

- Hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses (hepatocellular carcinoma)

- Human T-cell leukemia virus-1(T-cell leukemias).

- Merkel cell carcinoma)

Bacterial infection may also increase the risk of cancer, as seen in

Parasitic infections associated with cancer include:

- Schistosoma haematobium (squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder)

- The liver flukes, Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis (cholangiocarcinoma).[69]

Radiation

Radiation exposure such as

Ionizing radiation is not a particularly strong mutagen.[73] Residential exposure to radon gas, for example, has similar cancer risks as passive smoking.[73] Radiation is a more potent source of cancer when combined with other cancer-causing agents, such as radon plus tobacco smoke.[73] Radiation can cause cancer in most parts of the body, in all animals and at any age. Children are twice as likely to develop radiation-induced leukemia as adults; radiation exposure before birth has ten times the effect.[73]

Medical use of ionizing radiation is a small but growing source of radiation-induced cancers. Ionizing radiation may be used to treat other cancers, but this may, in some cases, induce a second form of cancer.[73] It is also used in some kinds of medical imaging.[74]

Prolonged exposure to

Non-ionizing

Heredity

The vast majority of cancers are non-hereditary (sporadic).

Statistically for cancers causing most mortality, the

Taller people have an increased risk of cancer because they have more cells than shorter people. Since height is genetically determined to a large extent, taller people have a heritable increase of cancer risk.[85]

Physical agents

Some substances cause cancer primarily through their physical, rather than chemical, effects.

Physical trauma resulting in cancer is relatively rare.[87] Claims that breaking bones resulted in bone cancer, for example, have not been proven.[87] Similarly, physical trauma is not accepted as a cause for cervical cancer, breast cancer or brain cancer.[87] One accepted source is frequent, long-term application of hot objects to the body. It is possible that repeated burns on the same part of the body, such as those produced by kanger and kairo heaters (charcoal hand warmers), may produce skin cancer, especially if carcinogenic chemicals are also present.[87] Frequent consumption of scalding hot tea may produce esophageal cancer.[87] Generally, it is believed that cancer arises, or a pre-existing cancer is encouraged, during the process of healing, rather than directly by the trauma.[87] However, repeated injuries to the same tissues might promote excessive cell proliferation, which could then increase the odds of a cancerous mutation.[citation needed]

Chronic inflammation has been hypothesized to directly cause mutation.[87][88] Inflammation can contribute to proliferation, survival, angiogenesis and migration of cancer cells by influencing the tumor microenvironment.[89][90] Oncogenes build up an inflammatory pro-tumorigenic microenvironment.[91]

Hormones

Hormones also play a role in the development of cancer by promoting cell proliferation.[92] Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins play a key role in cancer cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, suggesting possible involvement in carcinogenesis.[93]

Hormones are important agents in sex-related cancers, such as cancer of the breast,

Other factors are relevant: obese people have higher levels of some hormones associated with cancer and a higher rate of those cancers.

Autoimmune diseases

There is an association between

Pathophysiology

Genetics

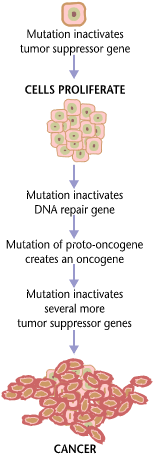

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of tissue growth regulation. For a normal cell to transform into a cancer cell, the genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered.[96]

The affected genes are divided into two broad categories. Oncogenes are genes that promote cell growth and reproduction. Tumor suppressor genes are genes that inhibit cell division and survival. Malignant transformation can occur through the formation of novel oncogenes, the inappropriate over-expression of normal oncogenes, or by the under-expression or disabling of tumor suppressor genes. Typically, changes in multiple genes are required to transform a normal cell into a cancer cell.[97]

Genetic changes can occur at different levels and by different mechanisms. The gain or loss of an entire chromosome can occur through errors in mitosis. More common are mutations, which are changes in the nucleotide sequence of genomic DNA.

Large-scale mutations involve the deletion or gain of a portion of a chromosome. Genomic amplification occurs when a cell gains copies (often 20 or more) of a small chromosomal locus, usually containing one or more oncogenes and adjacent genetic material. Translocation occurs when two separate chromosomal regions become abnormally fused, often at a characteristic location. A well-known example of this is the Philadelphia chromosome, or translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22, which occurs in chronic myelogenous leukemia and results in production of the BCR-abl fusion protein, an oncogenic tyrosine kinase.

Small-scale mutations include point mutations, deletions, and insertions, which may occur in the

Replication of the data contained within the DNA of living cells will probabilistically result in some errors (mutations). Complex error correction and prevention are built into the process and safeguard the cell against cancer. If a significant error occurs, the damaged cell can self-destruct through programmed cell death, termed apoptosis. If the error control processes fail, then the mutations will survive and be passed along to daughter cells.

Some environments make errors more likely to arise and propagate. Such environments can include the presence of disruptive substances called

The errors that cause cancer are self-amplifying and compounding, for example:

- A mutation in the error-correcting machinery of a cell might cause that cell and its children to accumulate errors more rapidly.

- A further mutation in an oncogene might cause the cell to reproduce more rapidly and more frequently than its normal counterparts.

- A further mutation may cause loss of a tumor suppressor gene, disrupting the apoptosis signaling pathway and immortalizing the cell.

- A further mutation in the signaling machinery of the cell might send error-causing signals to nearby cells.

The transformation of a normal cell into cancer is akin to a chain reaction caused by initial errors, which compound into more severe errors, each progressively allowing the cell to escape more controls that limit normal tissue growth. This rebellion-like scenario is an undesirable survival of the fittest, where the driving forces of evolution work against the body's design and enforcement of order. Once cancer has begun to develop, this ongoing process, termed clonal evolution, drives progression towards more invasive stages.[99] Clonal evolution leads to intra-tumour heterogeneity (cancer cells with heterogeneous mutations) that complicates designing effective treatment strategies and requires an evolutionary approach to designing treatment.

Characteristic abilities developed by cancers are divided into categories, specifically evasion of apoptosis, self-sufficiency in growth signals, insensitivity to anti-growth signals, sustained angiogenesis, limitless replicative potential, metastasis, reprogramming of energy metabolism and evasion of immune destruction.[30][31]

Epigenetics

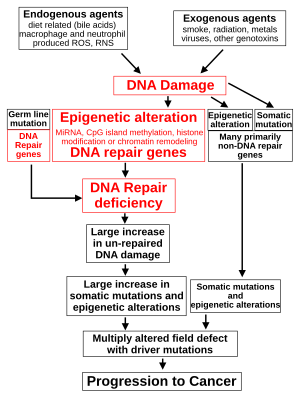

The classical view of cancer is a set of diseases driven by progressive

Epigenetic alterations occur frequently in cancers. As an example, one study listed protein coding genes that were frequently altered in their methylation in association with colon cancer. These included 147 hypermethylated and 27 hypomethylated genes. Of the hypermethylated genes, 10 were hypermethylated in 100% of colon cancers and many others were hypermethylated in more than 50% of colon cancers.[103]

While epigenetic alterations are found in cancers, the epigenetic alterations in DNA repair genes, causing reduced expression of DNA repair proteins, may be of particular importance. Such alterations may occur early in progression to cancer and are a possible cause of the genetic instability characteristic of cancers.[104][105][106]

Reduced expression of DNA repair genes disrupts DNA repair. This is shown in the figure at the 4th level from the top. (In the figure, red wording indicates the central role of DNA damage and defects in DNA repair in progression to cancer.) When DNA repair is deficient DNA damage remains in cells at a higher than usual level (5th level) and causes increased frequencies of mutation and/or epimutation (6th level). Mutation rates increase substantially in cells defective in DNA mismatch repair[107][108] or in homologous recombinational repair (HRR).[109] Chromosomal rearrangements and aneuploidy also increase in HRR defective cells.[110]

Higher levels of DNA damage cause increased mutation (right side of figure) and increased epimutation. During repair of DNA double strand breaks, or repair of other DNA damage, incompletely cleared repair sites can cause epigenetic gene silencing.[111][112]

Deficient expression of DNA repair proteins due to an inherited mutation can increase cancer risks. Individuals with an inherited impairment in any of 34 DNA repair genes (see article DNA repair-deficiency disorder) have increased cancer risk, with some defects ensuring a 100% lifetime chance of cancer (e.g. p53 mutations).[113] Germ line DNA repair mutations are noted on the figure's left side. However, such germline mutations (which cause highly penetrant cancer syndromes) are the cause of only about 1 percent of cancers.[114]

In sporadic cancers, deficiencies in DNA repair are occasionally caused by a mutation in a DNA repair gene but are much more frequently caused by epigenetic alterations that reduce or silence expression of DNA repair genes. This is indicated in the figure at the 3rd level. Many studies of heavy metal-induced carcinogenesis show that such heavy metals cause a reduction in expression of DNA repair enzymes, some through epigenetic mechanisms. DNA repair inhibition is proposed to be a predominant mechanism in heavy metal-induced carcinogenicity. In addition, frequent epigenetic alterations of the DNA sequences code for small RNAs called microRNAs (or miRNAs). miRNAs do not code for proteins, but can "target" protein-coding genes and reduce their expression.

Cancers usually arise from an assemblage of mutations and epimutations that confer a selective advantage leading to clonal expansion (see Field defects in progression to cancer). Mutations, however, may not be as frequent in cancers as epigenetic alterations. An average cancer of the breast or colon can have about 60 to 70 protein-altering mutations, of which about three or four may be "driver" mutations and the remaining ones may be "passenger" mutations.[115]

Metastasis

Metastasis is the spread of cancer to other locations in the body. The dispersed tumors are called metastatic tumors, while the original is called the primary tumor. Almost all cancers can metastasize.[39] Most cancer deaths are due to cancer that has metastasized.[40]

Metastasis is common in the late stages of cancer and it can occur via the blood or the lymphatic system or both. The typical steps in metastasis are local invasion, intravasation into the blood or lymph, circulation through the body, extravasation into the new tissue, proliferation and angiogenesis. Different types of cancers tend to metastasize to particular organs, but overall the most common places for metastases to occur are the lungs, liver, brain and the bones.[39]

Metabolism

Normal cells typically generate only about 30% of energy from glycolysis,[116] whereas most cancers rely on glycolysis for energy production (Warburg effect).[117][118] But a minority of cancer types rely on oxidative phosphorylation as the primary energy source, including lymphoma, leukemia, and endometrial cancer.[119] Even in these cases, however, the use of glycolysis as an energy source rarely exceeds 60%.[116] A few cancers use glutamine as the major energy source, partly because it provides nitrogen required for nucleotide (DNA, RNA) synthesis.[120] Cancer stem cells often use oxidative phosphorylation or glutamine as a primary energy source.[121]

Diagnosis

Most cancers are initially recognized either because of the appearance of signs or symptoms or through screening.[122] Neither of these leads to a definitive diagnosis, which requires the examination of a tissue sample by a pathologist.[123] People with suspected cancer are investigated with medical tests. These commonly include blood tests, X-rays, (contrast) CT scans and endoscopy.

The tissue

Cytogenetics and immunohistochemistry are other types of tissue tests. These tests provide information about molecular changes (such as mutations, fusion genes and numerical chromosome changes) and may thus also indicate the prognosis and best treatment.

Cancer diagnosis can cause psychological distress and psychosocial interventions, such as talking therapy, may help people with this.[124] Some people choose to disclose the diagnosis widely; others prefer to keep the information private, especially shortly after the diagnosis, or to disclose it only partially or to selected people.[125]

Classification

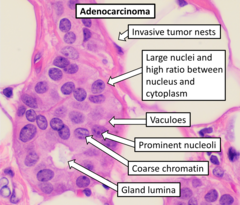

Cancers are classified by the type of cell that the tumor cells resemble and is therefore presumed to be the origin of the tumor. These types include:

- Carcinoma: Cancers derived from epithelial cells. This group includes many of the most common cancers and include nearly all those in the breast, prostate, lung, pancreas and colon. Most of these are of the adenocarcinoma type, which means that the cancer has gland-like differentiation.

- Sarcoma: Cancers arising from connective tissue (i.e. bone, cartilage, fat, nerve), each of which develops from cells originating in mesenchymal cells outside the bone marrow.

- Lymphoma and leukemia: These two classes arise from hematopoietic (blood-forming) cells that leave the marrow and tend to mature in the lymph nodes and blood, respectively.[126]

- , respectively).

- Blastoma: Cancers derived from immature "precursor" cells or embryonic tissue.

Cancers are usually named using -carcinoma, -sarcoma or -blastoma as a suffix, with the Latin or Greek word for the

Benign tumors (which are not cancers) are named using -oma as a suffix with the organ name as the root. For example, a benign tumor of smooth muscle cells is called a leiomyoma (the common name of this frequently occurring benign tumor in the uterus is fibroid). Confusingly, some types of cancer use the -noma suffix, examples including melanoma and seminoma.

Some types of cancer are named for the size and shape of the cells under a microscope, such as giant cell carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma and small-cell carcinoma.

-

An invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast (pale area at the center) surrounded by spikes of whitish scar tissue and yellow fatty tissue

-

An invasivecolorectal carcinoma (top center) in a colectomyspecimen

-

Abronchiin a lung specimen

-

A large invasiveductal carcinoma in a mastectomyspecimen

-

Squamous cell carcinomawith typical histopathology features.

-

Histopathology of small-cell carcinoma, with typical findings.[127]

Prevention

Cancer prevention is defined as active measures to decrease cancer risk.[129] The vast majority of cancer cases are due to environmental risk factors. Many of these environmental factors are controllable lifestyle choices. Thus, cancer is generally preventable.[130] Between 70% and 90% of common cancers are due to environmental factors and therefore potentially preventable.[131]

Greater than 30% of cancer deaths could be prevented by avoiding risk factors including: tobacco,

In 2019, ~44% of all cancer deaths – or ~4.5 M deaths or ~105 million lost disability-adjusted life years – were due to known clearly preventable risk factors, led by smoking, alcohol use and high BMI, according to a GBD systematic analysis.[128]

Dietary

While many dietary recommendations have been proposed to reduce cancer risks, the evidence to support them is not definitive.

Medication

Medications can be used to prevent cancer in a few circumstances.

Vitamin supplementation does not appear to be effective at preventing cancer.[149] While low blood levels of vitamin D are correlated with increased cancer risk,[150][151][152] whether this relationship is causal and vitamin D supplementation is protective is not determined.[153][154] One 2014 review found that supplements had no significant effect on cancer risk.[154] Another 2014 review concluded that vitamin D3 may decrease the risk of death from cancer (one fewer death in 150 people treated over 5 years), but concerns with the quality of the data were noted.[155]

Vaccination

Vaccines have been developed that prevent infection by some carcinogenic viruses.[159] Human papillomavirus vaccine (Gardasil and Cervarix) decrease the risk of developing cervical cancer.[159] The hepatitis B vaccine prevents infection with hepatitis B virus and thus decreases the risk of liver cancer.[159] The administration of human papillomavirus and hepatitis B vaccinations is recommended where resources allow.[160]

Screening

Unlike diagnostic efforts prompted by

- Possible harms from the screening test: for example, X-ray images involve exposure to potentially harmful ionizing radiation

- The likelihood of the test correctly identifying cancer

- The likelihood that cancer is present: Screening is not normally useful for rare cancers.

- Possible harms from follow-up procedures

- Whether suitable treatment is available

- Whether early detection improves treatment outcomes

- Whether cancer will ever need treatment

- Whether the test is acceptable to the people: If a screening test is too burdensome (for example, extremely painful), then people will refuse to participate.[162]

- Cost

Recommendations

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

The

- Strongly recommends

- Recommend that Americans be screened for colorectal cancer via fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy starting at age 50 until age 75.[164]

- Evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against screening for skin cancer,[165] oral cancer,[166] lung cancer,[167] or prostate cancer in men under 75.[168]

- Routine screening is not recommended for bladder cancer,[169] testicular cancer,[170] ovarian cancer,[171] pancreatic cancer,[172] or prostate cancer.[173]

- Recommends Cochrane review concluded that breast cancer screening by mammography had no effect in reducing mortality because of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.[175]

Japan

Screens for

Genetic testing

| Gene | Cancer types |

|---|---|

| BRCA1, BRCA2 | Breast, ovarian, pancreatic |

| HNPCC, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, PMS2 | Colon, uterine, small bowel, stomach, urinary tract |

Genetic testing for individuals at high-risk of certain cancers is recommended by unofficial groups.[160][176] Carriers of these mutations may then undergo enhanced surveillance, chemoprevention, or preventative surgery to reduce their subsequent risk.[176]

Management

Many treatment options for cancer exist. The primary ones include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy and palliative care. Which treatments are used depends on the type, location and grade of the cancer as well as the patient's health and preferences. The treatment intent may or may not be curative.[citation needed]

Chemotherapy

It was found that providing combined cytotoxic drugs is better than a single drug, a process called the combination therapy, which has an advantage in the statistics of survival and response to the tumor and in the progress of the disease.[178] A Cochrane review concluded that combined therapy was more effective to treat metastasized breast cancer. However, generally it is not certain whether combination chemotherapy leads to better health outcomes, when both survival and toxicity are considered.[179]

Targeted therapy is a form of chemotherapy that targets specific molecular differences between cancer and normal cells. The first targeted therapies blocked the estrogen receptor molecule, inhibiting the growth of breast cancer. Another common example is the class of Bcr-Abl inhibitors, which are used to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).[4] Currently, targeted therapies exist for many of the most common cancer types, including bladder cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, leukemia, liver cancer, lung cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, skin cancer, and thyroid cancer as well as other cancer types.[180]

The efficacy of chemotherapy depends on the type of cancer and the stage. In combination with surgery, chemotherapy has proven useful in cancer types including breast cancer, colorectal cancer,

Radiation

Radiation therapy involves the use of ionizing radiation in an attempt to either cure or improve symptoms. It works by damaging the DNA of cancerous tissue, causing mitotic catastrophe resulting in the death of the cancer cells.[186] To spare normal tissues (such as skin or organs, which radiation must pass through to treat the tumor), shaped radiation beams are aimed from multiple exposure angles to intersect at the tumor, providing a much larger dose there than in the surrounding, healthy tissue. As with chemotherapy, cancers vary in their response to radiation therapy.[187][188][189]

Radiation therapy is used in about half of cases. The radiation can be either from internal sources (brachytherapy) or external sources. The radiation is most commonly low energy X-rays for treating skin cancers, while higher energy X-rays are used for cancers within the body.[190] Radiation is typically used in addition to surgery and or chemotherapy. For certain types of cancer, such as early head and neck cancer, it may be used alone.[191] Radiation therapy after surgery for brain metastases has been shown to not improve overall survival in patients compared to surgery alone.[192] For painful bone metastasis, radiation therapy has been found to be effective in about 70% of patients.[191]

Surgery

Surgery is the primary method of treatment for most isolated, solid cancers and may play a role in palliation and prolongation of survival. It is typically an important part of definitive diagnosis and staging of tumors, as biopsies are usually required. In localized cancer, surgery typically attempts to remove the entire mass along with, in certain cases, the lymph nodes in the area. For some types of cancer this is sufficient to eliminate the cancer.[181]

Palliative care

Palliative care is treatment that attempts to help the patient feel better and may be combined with an attempt to treat the cancer. Palliative care includes action to reduce physical, emotional, spiritual and psycho-social distress. Unlike treatment that is aimed at directly killing cancer cells, the primary goal of palliative care is to improve quality of life.

People at all stages of cancer treatment typically receive some kind of palliative care. In some cases,

- display low performance status, implying limited ability to care for themselves[193]

- received no benefit from prior evidence-based treatments[193]

- are not eligible to participate in any appropriate clinical trial[193]

- no strong evidence implies that treatment would be effective[193]

Palliative care may be confused with hospice and therefore only indicated when people approach end of life. Like hospice care, palliative care attempts to help the patient cope with their immediate needs and to increase comfort. Unlike hospice care, palliative care does not require people to stop treatment aimed at the cancer.

Multiple national medical guidelines recommend early palliative care for patients whose cancer has produced distressing symptoms or who need help coping with their illness. In patients first diagnosed with metastatic disease, palliative care may be immediately indicated. Palliative care is indicated for patients with a prognosis of less than 12 months of life even given aggressive treatment.[195][196][197]

Immunotherapy

A variety of therapies using immunotherapy, stimulating or helping the immune system to fight cancer, have come into use since 1997. Approaches include antibodies, checkpoint therapy, and adoptive cell transfer.[198]

Laser therapy

Laser therapy uses high-intensity light to treat cancer by shrinking or destroying tumors or precancerous growths. Lasers are most commonly used to treat superficial cancers that are on the surface of the body or the lining of internal organs. It is used to treat basal cell skin cancer and the very early stages of others like cervical, penile, vaginal, vulvar, and non-small cell lung cancer. It is often combined with other treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy. Laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy (LITT), or interstitial laser photocoagulation, uses lasers to treat some cancers using hyperthermia, which uses heat to shrink tumors by damaging or killing cancer cells. Laser are more precise than surgery and cause less damage, pain, bleeding, swelling, and scarring. A disadvantage is surgeons must have specialized training. It may be more expensive than other treatments.[199]

Alternative medicine

Complementary and alternative cancer treatments are a diverse group of therapies, practices and products that are not part of conventional medicine.[200] "Complementary medicine" refers to methods and substances used along with conventional medicine, while "alternative medicine" refers to compounds used instead of conventional medicine.[201] Most complementary and alternative medicines for cancer have not been studied or tested using conventional techniques such as clinical trials. Some alternative treatments have been investigated and shown to be ineffective but still continue to be marketed and promoted. Cancer researcher Andrew J. Vickers stated, "The label 'unproven' is inappropriate for such therapies; it is time to assert that many alternative cancer therapies have been 'disproven'."[202]

Prognosis

Survival rates vary by cancer type and by the stage at which it is diagnosed, ranging from majority survival to complete mortality five years after diagnosis. Once a cancer has metastasized, prognosis normally becomes much worse. About half of patients receiving treatment for invasive cancer (excluding carcinoma in situ and non-melanoma skin cancers) die from that cancer or its treatment.[25] A majority of cancer deaths are due to metastases of the primary tumor.[204]

Survival is worse in the

Those who survive cancer develop a second primary cancer at about twice the rate of those never diagnosed.[206] The increased risk is believed to be due to the random chance of developing any cancer, the likelihood of surviving the first cancer, the same risk factors that produced the first cancer, unwanted side effects of treating the first cancer (particularly radiation therapy), and better compliance with screening.[206]

Predicting short- or long-term survival depends on many factors. The most important are the cancer type and the patient's age and overall health. Those who are frail with other health problems have lower survival rates than otherwise healthy people. Centenarians are unlikely to survive for five years even if treatment is successful. People who report a higher quality of life tend to survive longer.[207] People with lower quality of life may be affected by depression and other complications and/or disease progression that both impairs quality and quantity of life. Additionally, patients with worse prognoses may be depressed or report poorer quality of life because they perceive that their condition is likely to be fatal.

People with cancer have an increased risk of

Although extremely rare, some forms of cancer, even from an advanced stage, can heal spontaneously. This phenomenon is known as the spontaneous remission.[209]

Epidemiology

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Estimates are that in 2018, 18.1 million new cases of cancer and 9.6 million deaths occur globally.[211] About 20% of males and 17% of females will get cancer at some point in time while 13% of males and 9% of females will die from it.[211]

In 2008, approximately 12.7 million cancers were

Deaths from cancer were 5.8 million in 1990.[212] Deaths have been increasing primarily due to longer lifespans and lifestyle changes in the developing world.[25] The most significant risk factor for developing cancer is age.[213] Although it is possible for cancer to strike at any age, most patients with invasive cancer are over 65.[213] According to cancer researcher Robert A. Weinberg, "If we lived long enough, sooner or later we all would get cancer."[214] Some of the association between aging and cancer is attributed to immunosenescence,[215] errors accumulated in DNA over a lifetime[216] and age-related changes in the endocrine system.[217] Aging's effect on cancer is complicated by factors such as DNA damage and inflammation promoting it and factors such as vascular aging and endocrine changes inhibiting it.[218]

Some slow-growing cancers are particularly common, but often are not fatal. Autopsy studies in Europe and Asia showed that up to 36% of people have undiagnosed and apparently harmless thyroid cancer at the time of their deaths and that 80% of men develop prostate cancer by age 80.[219][220] As these cancers do not cause the patient's death, identifying them would have represented overdiagnosis rather than useful medical care.

The three most common childhood cancers are leukemia (34%), brain tumors (23%) and lymphomas (12%).[221] In the United States cancer affects about 1 in 285 children.[222] Rates of childhood cancer increased by 0.6% per year between 1975 and 2002 in the United States[223] and by 1.1% per year between 1978 and 1997 in Europe.[221] Death from childhood cancer decreased by half between 1975 and 2010 in the United States.[222]

History

Cancer has existed for all of human history.

In the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, it became acceptable for doctors to

The physician John Hill described

Society and culture

Although many diseases (such as heart failure) may have a worse prognosis than most cases of cancer, cancer is the subject of widespread fear and taboos. The euphemism of "a long illness" to describe cancers leading to death is still commonly used in obituaries, rather than naming the disease explicitly, reflecting an apparent stigma.[231] Cancer is also euphemised as "the C-word";[232][233][234] Macmillan Cancer Support uses the term to try to lessen the fear around the disease.[235] In Nigeria, one local name for cancer translates into English as "the disease that cannot be cured".[236] This deep belief that cancer is necessarily a difficult and usually deadly disease is reflected in the systems chosen by society to compile cancer statistics: the most common form of cancer—non-melanoma skin cancers, accounting for about one-third of cancer cases worldwide, but very few deaths[237][238]—are excluded from cancer statistics specifically because they are easily treated and almost always cured, often in a single, short, outpatient procedure.[239]

Western conceptions of patients' rights for people with cancer include a duty to fully disclose the medical situation to the person, and the right to engage in shared decision-making in a way that respects the person's own values. In other cultures, other rights and values are preferred. For example, most African cultures value whole families rather than individualism. In parts of Africa, a diagnosis is commonly made so late that cure is not possible, and treatment, if available at all, would quickly bankrupt the family. As a result of these factors, African healthcare providers tend to let family members decide whether, when and how to disclose the diagnosis, and they tend to do so slowly and circuitously, as the person shows interest and an ability to cope with the grim news.[236] People from Asian and South American countries also tend to prefer a slower, less candid approach to disclosure than is idealized in the United States and Western Europe, and they believe that sometimes it would be preferable not to be told about a cancer diagnosis.[236] In general, disclosure of the diagnosis is more common than it was in the 20th century, but full disclosure of the prognosis is not offered to many patients around the world.[236]

In the United States and some other cultures, cancer is regarded as a disease that must be "fought" to end the "civil insurrection"; a

One idea about why people with cancer are blamed or stigmatized, called the just-world hypothesis, is that blaming cancer on the patient's actions or attitudes allows the blamers to regain a sense of control. This is based upon the blamers' belief that the world is fundamentally just and so any dangerous illness, like cancer, must be a type of punishment for bad choices, because in a just world, bad things would not happen to good people.[244]

Economic effect

The total health care expenditure on cancer in the US was estimated to be $80.2 billion in 2015.[245] Even though cancer-related health care expenditure have increased in absolute terms during recent decades, the share of health expenditure devoted to cancer treatment has remained close to 5% between the 1960s and 2004.[246][247] A similar pattern has been observed in Europe where about 6% of all health care expenditure are spent on cancer treatment.[248][249] In addition to health care expenditure and financial toxicity, cancer causes indirect costs in the form of productivity losses due to sick days, permanent incapacity and disability as well as premature death during working age. Cancer causes also costs for informal care. Indirect costs and informal care costs are typically estimated to exceed or equal the health care costs of cancer.[250][249]

Workplace

In the United States, cancer is included as a protected condition by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), mainly due to the potential for cancer having discriminating effects on workers.[251] Discrimination in the workplace could occur if an employer holds a false belief that a person with cancer is not capable of doing a job properly, and may ask for more sick leave than other employees. Employers may also make hiring or firing decisions based on misconceptions about cancer disabilities, if present. The EEOC provides interview guidelines for employers, as well as lists of possible solutions for assessing and accommodating employees with cancer.[251]

Divorce gender disparity

Women are six times more likely to be separated or

Research

Because cancer is a class of diseases,

Experimental cancer treatments are studied in clinical trials to compare the proposed treatment to the best existing treatment. Treatments that succeeded in one cancer type can be tested against other types.[259] Diagnostic tests are under development to better target the right therapies to the right patients, based on their individual biology.[260]

Cancer research focuses on the following issues:

- Agents (e.g. viruses) and events (e.g. mutations) that cause or facilitate genetic changes in cells destined to become cancer.

- The precise nature of the genetic damage and the genes that are affected by it.

- The consequences of those genetic changes on the biology of the cell, both in generating the defining properties of a cancer cell and in facilitating additional genetic events that lead to further progression of the cancer.

The improved understanding of

Competition for financial resources appears to have suppressed the creativity, cooperation, risk-taking and original thinking required to make fundamental discoveries, unduly favoring low-risk research into small incremental advancements over riskier, more innovative research. Other consequences of competition appear to be many studies with dramatic claims whose results cannot be replicated and perverse incentives that encourage grantee institutions to grow without making sufficient investments in their own faculty and facilities.[263][262][264][265]

Virotherapy, which uses convert viruses, is being studied.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a worry that cancer research and treatment are slowing down.[266][267]

On 2 December 2023 Nano Today published a groundbreaking discovery involving "NK cell-engaging nanodrones" for targeted cancer treatment. The development of "NK cell-engaging nanodrones" represents a significant leap forward in cancer treatment, showcasing how cutting-edge nanotechnology and immunotherapy can be combined to target and eliminate cancer cells with unprecedented precision. These nanodrones are designed to harness the power of natural killer (NK) cells, which play a crucial role in the body's immune response against tumors. By directing these NK cells specifically to the sites of tumors, the nanodrones can effectively concentrate the immune system's attack on the cancer cells, potentially leading to better outcomes for patients.[268]

The key innovation here lies in the use of protein cage nanoparticle-based systems. These systems are engineered to carry signals that attract NK cells directly to the tumor, overcoming one of the major challenges in cancer immunotherapy: ensuring that the immune cells find and attack only the cancer cells without harming healthy tissue. This targeted approach not only increases the efficacy of the treatment but also minimizes side effects, a common concern with broader-acting cancer therapies.[268]

Pregnancy

Cancer affects approximately 1 in 1,000 pregnant women. The most common cancers found during pregnancy are the same as the most common cancers found in non-pregnant women during childbearing ages: breast cancer, cervical cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, ovarian cancer and colorectal cancer.[269]

Diagnosing a new cancer in a pregnant woman is difficult, in part because any symptoms are commonly assumed to be a normal discomfort associated with pregnancy. As a result, cancer is typically discovered at a somewhat later stage than average. Some imaging procedures, such as MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging), CT scans, ultrasounds and mammograms with fetal shielding are considered safe during pregnancy; some others, such as PET scans, are not.[269]

Treatment is generally the same as for non-pregnant women. However, radiation and radioactive drugs are normally avoided during pregnancy, especially if the fetal dose might exceed 100 cGy. In some cases, some or all treatments are postponed until after birth if the cancer is diagnosed late in the pregnancy. Early deliveries are often used to advance the start of treatment. Surgery is generally safe, but pelvic surgeries during the first trimester may cause miscarriage. Some treatments, especially certain chemotherapy drugs given during the

Elective abortions are not required and, for the most common forms and stages of cancer, do not improve the mother's survival. In a few instances, such as advanced uterine cancer, the pregnancy cannot be continued and in others, the patient may end the pregnancy so that she can begin aggressive chemotherapy.[269]

Some treatments can interfere with the mother's ability to give birth vaginally or to breastfeed.[269] Cervical cancer may require birth by Caesarean section. Radiation to the breast reduces the ability of that breast to produce milk and increases the risk of mastitis. Also, when chemotherapy is given after birth, many of the drugs appear in breast milk, which could harm the baby.[269]

Other animals

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Veterinary oncology, concentrating mainly on cats and dogs, is a growing specialty in wealthy countries and the major forms of human treatment such as surgery and radiotherapy may be offered. The most common types of cancer differ, but the cancer burden seems at least as high in pets as in humans. Animals, typically rodents, are often used in cancer research and studies of natural cancers in larger animals may benefit research into human cancer.[270]

Across wild animals, there is still limited data on cancer. Nonetheless, a study published in 2022, explored cancer risk in (non-domesticated) zoo mammals, belonging to 191 species, 110,148 individual, demonstrated that cancer is a ubiquitous disease of mammals and it can emerge anywhere along the mammalian phylogeny.

In non-humans, a few types of

References

- ^ a b c "Cancer – Signs and symptoms". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Cancer". World Health Organization. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ PMID 18626751.

- ^ a b c "Targeted Cancer Therapies". cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: All Cancer Sites". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ PMID 34967848.

- ^ a b c d "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Obesity and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 3 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- PMID 26400678.

- ^ "Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis – The Lancet Global Health".

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the originalon 12 July 2017.

- ^ "Heredity and Cancer". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "How is cancer diagnosed?". American Cancer Society. 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ S2CID 2067308.

- PMID 22158327.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the originalon 12 July 2017.

- PMID 23737396.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the originalon 12 July 2017.

- PMID 27733282.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ PMID 36633525.

- PMID 23369588.

- PMID 23084294.

- ^ S2CID 30500384.

- ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the originalon 12 July 2017.

- ^ "cancer". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022.

- ^ "Cancer Glossary". cancer.org. American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ^ "What is cancer?". cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ S2CID 1478778.

- ^ PMID 21376230.

- ^ a b c Holland Chp. 1

- S2CID 45874503.

- ISBN 978-1-933864-33-4.

- PMID 21296615.

- ^ "Shortness of Breath | Cancer-related Side Effects". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- PMID 33289989.

- PMID 28341725.

- ^ a b c d "Metastatic Cancer: Questions and Answers". National Cancer Institute. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b "What is Metastasized Cancer?". National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "Why is cancer so hard to cure?". The Age. 15 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Share of cancer deaths attributed to tobacco". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-387-78193-8.

The term environment refers not only to air, water, and soil but also to substances and conditions at home and at the workplace, including diet, smoking, alcohol, drugs, exposure to chemicals, sunlight, ionizing radiation, electromagnetic fields, infectious agents, etc. Lifestyle, economic and behavioral factors are all aspects of our environment.

- PMID 29160902.

- ^ PMID 29949726.

the strongest conclusion derived from decades of research on stressors and cancer is that stressful events may be associated with decreased cancer survival but are probably not associated with disease incidence (Chida et al. 2008).

- PMID 23393080.

- ^ PMID 35420163.

- S2CID 34197973.

- S2CID 20891885.

- S2CID 6132726.

- ^ CDC (27 August 2019). "Cancer and Tobacco Use". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ S2CID 9172672.

- PMID 15552776.

- PMID 16998161.

- PMID 18434333.

- PMID 21474525.

- PMID 18055160.

- ^ a b "WHO calls for prevention of cancer through healthy workplaces" (Press release). World Health Organization. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Erin Brockovich Blasts U.S. Regulation of Toxic Chemicals". scientificamerican.com. Scientific American. 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Environmental Pollutant, PFOA, Associated with Increased Risk of Kidney Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 24 September 2020.

- ^ S2CID 19823935.

- PMID 25129328.

- ^ PMID 18990005. Archived from the originalon 4 September 2011.

- PMID 19107449.

- PMID 14278899.

- PMID 21102637.

- PMID 15489139.

- PMID 24559558.

- from the original on 4 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Radiation". National Cancer Institute. 29 April 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ a b c "Sunlight". National Cancer Institute. 29 April 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "Cancer prevention". WHO. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55009-113-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2016.

- S2CID 2760372.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55009-113-7. Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ "IARC classifies radiofrequency electromagnetic fields as possibly carcinogenic to humans" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Electromagnetic Fields and Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "Cell Phones and Cancer Risk – National Cancer Institute". Cancer.gov. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ S2CID 24746283.

- S2CID 25299272.

- PMID 17220324.

- PMID 22436981.

- S2CID 25591527.

- PMID 12677142.

- PMID 21782509.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55009-113-7. Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55009-113-7. Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- PMID 19468060.

- PMID 21914164.

- PMID 20455855.

- PMID 18502035.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55009-113-7. Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- PMID 19142965.

- PMID 26402826.

- PMID 27239106.

- S2CID 8813076.

- S2CID 20201610.

- PMID 15314031.

- S2CID 8040576.

- S2CID 2514545.

- PMID 22082348.

- PMID 12640109./

- PMID 22389639.

- PMID 17412712.

- PMID 21278452.

- PMID 23671730.

- PMID 9096356.

- PMID 16728433.

- PMID 11850397.

- PMID 5770175.

- PMID 18704159.

- PMID 17616978.

- PMID 21779515.

- PMID 9353177.

- PMID 23539594.

- ^ PMID 23226794.

- PMID 20181022.

- PMID 31781842.

- S2CID 222214285.

- PMID 26771115.

- PMID 32670883.

- ^ "Cancer Screening Guidelines | Detecting Cancer Early". American Cancer Society. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ISBN 9781550092134.

- PMID 23152241.

- ^ Pearson, Catherine (10 January 2024). "Why Some People Keep Serious Illnesses Private". The New York Times.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-3276-9.

- ^ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD. Source for findings: Caroline I.M. Underwood, M.D., Carolyn Glass, M.D., Ph.D. "Lung - Small cell carcinoma". Pathology Outlines.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Last author update: 20 September 2022 - ^ PMID 35988567.

- ^ "Cancer prevention: 7 steps to reduce your risk". Mayo Clinic. 27 September 2008. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- S2CID 17354479.

- PMID 26675728.

- ^ "Cancer". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- PMID 23641414.

- ^ PMID 21904992.

- PMID 22202045.

- PMID 21119663.

- PMID 25073782.

- PMID 17484871.

- PMID 19838915.

- PMID 20374790.

- ^ Staff (26 October 2015). "World Health Organization – IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat" (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ Hauser, Christine (26 October 2015). "W.H.O. Report Links Some Cancers With Processed or Red Meat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ Holland Chp.33

- PMID 17339623.

- S2CID 22950940.

- PMID 20594533.

- PMID 19020189.

- PMID 18425978.

- from the original on 25 May 2012.

- PMID 16595781.

- ^ "Vitamin D Has Role in Colon Cancer Prevention". Archived from the original on 4 December 2006. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- PMID 23094923.

- PMID 16595770.

- ^ PMID 24703049.

- S2CID 205189615.

- PMID 21738614.

- PMID 17551129.

- PMID 29376219.

- ^ a b c "Cancer Vaccine Fact Sheet". NCI. 8 June 2006. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ PMID 24176569.

- ^ a b c "Cancer Screening Overview (PDQ®)–Patient Version". National Cancer Institute. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Wilson JMG, Jungner G. (1968) Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: World Health Organization. Public Health Papers, No. 34.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2003. Archived from the originalon 23 December 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008. Archived from the originalon 7 February 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2009. Archived from the originalon 8 January 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2004. Archived from the originalon 24 October 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2004. Archived from the originalon 4 November 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008. Archived from the originalon 31 December 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2004. Archived from the originalon 23 August 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2004. Archived from the originalon 15 May 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2004. Archived from the originalon 23 October 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2004. Archived from the originalon 21 November 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- PMID 21984740.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2009. Archived from the originalon 2 January 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- PMID 23737396.

- ^ S2CID 29630942.

- .

- ^ Emil Frei, I. I. I.; Eder, Joseph Paul (2003). Combination Chemotherapy. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- PMID 24347031.

- ^ "Targeted Cancer Therapies". About Cancer. National Cancer Institute. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b Holland Chp. 40

- PMID 22730604.

- S2CID 35447562.

- PMID 15146036.

- PMID 20171403.

- S2CID 22483746.

- ^ CK Bomford, IH Kunkler, J Walter. Walter and Miller's Textbook of Radiation therapy (6th Ed), p311

- ^ McMorran, Jim; Crowther, Damian; McMorran, Stew; Youngmin, Steve; Wacogne, Ian; Pleat, Jon; Prince, Clive. "tumour radiosensitivity – General Practice Notebook". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Tidy C (23 December 2015). "Radiotherapy". Patient UK. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Last Checked: 23 December 2015

- S2CID 18082594.

- ^ a b Holland Chp. 41

- ^ "Radiation Therapy for Brain Metastases: A Systematic Review". PCORI. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e American Society of Clinical Oncology. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ * The American Society of Clinical Oncology made this recommendation based on various cancers. See American Society of Clinical Oncology. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- for lung cancer, see Azzoli CG, Temin S, Aliff T, Baker S, Brahmer J, Johnson DH, Laskin JL, Masters G, Milton D, Nordquist L, Pao W, Pfister DG, Piantadosi S, Schiller JH, Smith R, Smith TJ, Strawn JR, Trent D, Giaccone G (October 2011). "2011 Focused Update of 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update on Chemotherapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (28): 3825–31. PMID 20679538.

- for breast cancer, see Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, Burstein HJ, Carter WB, Edge SB, et al. (February 2009). "Breast cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 7 (2): 122–92. PMID 19200416.

- for colon cancer, see Engstrom PF, Arnoletti JP, Benson AB, Chen YJ, Choti MA, Cooper HS, Covey A, Dilawari RA, Early DS, Enzinger PC, Fakih MG, Fleshman J, Fuchs C, Grem JL, Kiel K, Knol JA, Leong LA, Lin E, Mulcahy MF, Rao S, Ryan DP, Saltz L, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous C, Thomas J, Venook AP, Willett C (September 2009). "NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: colon cancer". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 7 (8): 778–831. PMID 19755046.

- for other general statements see Smith TJ, Hillner BE (May 2011). "Bending the cost curve in cancer care". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (21): 2060–5. S2CID 40873748.

- for lung cancer, see Azzoli CG, Temin S, Aliff T, Baker S, Brahmer J, Johnson DH, Laskin JL, Masters G, Milton D, Nordquist L, Pao W, Pfister DG, Piantadosi S, Schiller JH, Smith R, Smith TJ, Strawn JR, Trent D, Giaccone G (October 2011). "2011 Focused Update of 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update on Chemotherapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (28): 3825–31.

- ^ "NCCN Guidelines". Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care" (PDF). The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

- S2CID 44343423.

- S2CID 9745527.

- ^ "Lasers in Cancer Treatment". National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- S2CID 6453919.

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- S2CID 35124492.

- ^ "Three measures of cancer mortality". Our World in Data. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- PMID 34164589.

- ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the originalon 12 July 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55009-213-4.

- PMID 20030832.

- ^ PMID 28892556.

- ^ Radha G., Lopus M. (2021) The spontaneous remission of cancer: Current insights and therapeutic significance. Translational Oncology. 14 (9):101166, doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101166

- ^ "Cancer death rates". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Latest global cancer data: Cancer burden rises to 18.1 million new cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths in 2018" (PDF). iarc.fr. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ S2CID 1541253.

- ^ ]

- ^ Johnson G (28 December 2010). "Unearthing Prehistoric Tumors, and Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017.

- PMID 20656212.

- ISBN 978-0-8153-4072-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2016.

A certain irreducible background incidence of cancer is to be expected regardless of circumstances: mutations can never be absolutely avoided, because they are an inescapable consequence of fundamental limitations on the accuracy of DNA replication, as discussed in Chapter 5. If a human could live long enough, it is inevitable that at least one of his or her cells would eventually accumulate a set of mutations sufficient for cancer to develop.

- S2CID 17412298.

- S2CID 5726826.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974797-9.

- ISBN 978-0-323-01970-5.

- ^ PMID 20231056.

- ^ S2CID 34364885.

- S2CID 1579801.

- ^ S2CID 39667103.

- ^ Paul of Aegina, 7th century AD, quoted in Moss, Ralph W. (2004). "Galen on Cancer". CancerDecisions. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Referenced from Michael Shimkin, Contrary to Nature, Washington, DC: Superintendent of Document, DHEW Publication No. (NIH) 79–720, p. 35.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974892-1. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ^ S2CID 28148111.

- ISBN 978-0-679-43459-7.

- S2CID 38892895.

- PMID 12042378.

- ISSN 0017-789X. Archived from the originalon 8 November 2013.

- S2CID 160969212. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Wollaston, Sam (4 May 2015). "The C-Word review – a wonderful testament to a woman who faced cancer with honesty, verve and wit". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "Avoiding the 'C' Word for Low-Risk Thyroid Cancer". Medscape. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "The C word: how we react to cancer today". NHS Networks. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-530107-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ "Skin cancers". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ]

- ISBN 978-0-521-64964-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974993-5.

- ^ OCLC 186453370.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8050-8749-9.

- ^ Huff C (24 September 2013). "A Sick Stigma: Why are cancer patients blamed for their illness?". Slate. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013.

- ^ "Economic Impact of Cancer". American Cancer Society. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- PMID 15337487.

- PMID 21228314.

- PMID 27589247.

- ^ PMID 32120274.

- PMID 24131614.

- ^ a b U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Questions & Answers about Cancer in the Workplace and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)." https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/cancer.cfm

- ^ "Men Leave: Separation and Divorce Far More Common when the Wife is the Patient".

- ^ "Men more likely than women to leave partner with cancer". Reuters. 12 November 2009.

- ^ "What Is Cancer?". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Cancer Fact Sheet". Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. 30 August 2002. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ Wanjek C (16 September 2006). "Exciting New Cancer Treatments Emerge Amid Persistent Myths". Live Science. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- PMID 19360048.

- PMID 20189876.

- S2CID 25267555.

- S2CID 43505621.

- ^ Begley S (16 September 2008). "Rethinking the War on Cancer". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ a b Kolata G (23 April 2009). "Advances Elusive in the Drive to Cure Cancer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- PMID 24733905.

- ^ Kolata G (27 June 2009). "Grant System Leads Cancer Researchers to Play It Safe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- S2CID 4465686.

- ^ "Opinion | I'm an oncologist. My worst fears about Covid and cancer are coming true". NBC News. 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Don't sacrifice cancer care to COVID". New York Daily News. 13 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Revolutionary nanodrones enable targeted cancer treatment". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7637-6357-2.

- (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- S2CID 245425871.

- PMID 16901782.

Further reading

- Bast RC, Croe CM, Hait WN, Hong WK, Kufe DW, Piccart-Gebhart M, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, Yang H, Holland JF (2016). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-93469-2.

- Kleinsmith LJ (2006). Principles of cancer biology. Pearson Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4003-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4391-0795-9. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Pazdur R, Camphausen KA, Wagman LD, Hoskins WJ (2009). Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cmp United Business Media. on 15 May 2009.

- Schwab M (2008). Encyclopedia of Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-36847-2.

- Tannock I (2005). The basic science of oncology. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-138774-3.

![Histopathology of small-cell carcinoma, with typical findings.[127]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Histopathology_of_small_cell_carcinoma%2C_annotated.png/120px-Histopathology_of_small_cell_carcinoma%2C_annotated.png)