Kafr Saba

Kafr Saba

كفر سابا | |

|---|---|

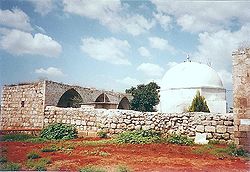

Mausoleum of Nabi Yamin, with riwaq (prayer hall) to the left. | |

| Etymology: the village of Sâba (from Aramaic )[1] | |

A series of historical maps of the area around Kafr Saba (click the buttons) | |

Tulkarm | |

| Date of depopulation | 15 May 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,688 dunams (9.688 km2 or 3.741 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,270[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Hak'ramim,[5] Beit Berl, Kfar Saba, Neve Yamin |

Kafr Saba (

The village was

Much of the village's ruins were built over as the neighboring Israeli town of Kfar Saba expanded in the late 20th century; the location of the built-up area of the village is now the Shikun Kaplan area of Kfar Saba, and part of it is known as the "Kfar Saba Archaeological Garden" or "Tel Kfar Saba".

Two domed maqams remain, located on either side of Route 55 between Kfar Saba and Qalqilya. The larger of the two is called the Tomb of Benjamin and is situated on the east side. About 40 meters (44 yd) away, on the west side of the road, is a much smaller shrine named Nabi Serakha.[13] The Tomb of Benjamin shrine sits on what has historically been considered by Jews to be the biblical character Benjamin[14] and was later taken over by the Breslov sect of Haredi Judaism.

History

The origins of the name are not known – in Hebrew and Aramaic, it means 'grandfather village'. Residents of the village were said to be Hebronites who migrated to the area due to crop failures.[10]

Antiquity

Excavations in Kafr Saba have revealed the remains of a large

In the Byzantine periods the ruins of the bathhouse were first converted into fish pools, and later into some form of industrial installation.[16]

Samaritan author Benyamim Tsedaka names the Baalah family as a Samaritan family who resided in Kafr Saba before their destruction or conversion.[17]

Around the year 985, al-Maqdisi described the place as a large village with a mosque that was situated on the road to Damascus.[9][18] In 1047 Nasir Khusraw described it as a town on the road to Ramla rich in fig and olive trees.[9]

A five-line inscription recording the grave of Sayf al-Din Bari, dated 1299–1300 CE was recorded within the shrine enclosure in 1922. The present location of this inscription is unknown.[19] A sabil or public water fountain is situated on the east side of the main enclosure. An inscription embedded on the right side of the sabil referred to the foundation of a fountain for the public by Tankiz, governor of Damascus in 1311–1312.[20]

Ottoman era

In 1596, Kafr Saba was part of the

In 1730, the Egyptian

In the 1860s, the Ottoman authorities granted the village an agricultural plot of land called Ghabat Kafr Saba in the former confines of the Forest of Arsur (Ar. al-Ghaba) in the coastal plain west of the village.[23][24]

In the 1870s, the village of Kafr Saba was described as a village built of stone and adobe brick and was situated on a low hill. It contained a mosque and was surrounded by sandy ground with olive groves to the north. Its population was estimated to be 800.[25]

In 1870/1871 (1288

Part of the village was sold to the Jewish Colonisation Association during the Ottoman period. Jewish immigrants to Palestine established a moshava on the land and called it Kfar Saba.[27]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census there were 546 villagers, all Muslim,[28] increasing in the 1931 census to a population of 765, still all Muslims, in a total of 169 houses.[29]

The village expanded in the British Mandate period; new houses were built along the highway, and new agricultural land were cultivated to the west of the village.[9] In the 1945 statistics it had population of 1,270 Muslims,[2] while the total land area was 9,688 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[3] Of this, 1,026 dunums were used for citrus and bananas, 4,600 dunums for cereals, while 355 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards, of which 30 dunums were planted with olive trees.[30]

1948 War and aftermath

In the months leading up to the 1948 war, the local militia from Kafr Saba had attacked the neighboring Jewish town of

"The village site has been used for the construction of new residential quarters within an industrial area that is part of the settlement of Kefar Sava. Some of the old village houses have survived destruction and are located today within the settlement; a number of them are used as commercial buildings. The two shrines, the school, and the ruins of the village cemetery remain. The shrines have arched entrances and are surmounted with domes. The land around the site is cultivated by Israelis."[32]

After the war, the shrine near the town was abandoned. After 1967, the ruin was taken over by the

The Jewish town of Kfar Saba, founded in 1903, was situated southwest of the village on the eve of the war. Following the war, it expanded to cover much of the village land. The location of the built-up area of the village is now the Shikun Kaplan area of modern Kfar Saba, and part of it is known as the "Kfar Saba Archaeological Garden" or "Tel Kfar Saba".

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 174

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 21

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 75

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #193, Also gives the cause for depopulation

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xxii: settlement #106, 1949.

- ^ Masalha 2007, p. 69

- ^ Waked, Ali (2005-05-15), "Palestinians mark 'catastrophe'", Ynetnews, ynet, retrieved 2009-08-13

- ^ a b Vilnai, Ze'ev (1976). "Kefar-Sava". Ariel Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Vol. 4. Israel: Am Oved. pp. 3790–96.

- ^ a b c d e Khalidi, 1992, p. 555.

- ^ Geography Research Forum, 5, 1982, p. 64.

- ^ Benvenisti, 2002, p. 273

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, pp. 246-247

- ^ Petersen, 2001, pp. 233, 235

- )

- ^ a b The Origin of the Name Capharsaba Archived 2008-05-23 at the Wayback Machine Kfar Sava Municipal Council

- ^ According to Ayalon, 1982. Cited in Petersen, 2002, p.233

- ISBN 978-3-11-021283-9, retrieved 2024-03-06

- ^ Al-Maqdisi, cited in Le Strange, 1890, p. 471

- ^ Petersen, 2001, p. 235

- ^ Mayer, 1933, pp. 219-220, cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 235

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 140. Quoted in Khalidi, p. 555

- ^ Petersen, 2001, p. 234

- ^ Marom, Roy, "The Contribution of Conder's Tent Work in Palestine for the Understanding of Shifting Geographical, Social and Legal Realities in the Sharon during the Late Ottoman Period", in Gurevich D. and Kidron, A. (eds.), Exploring the Holy Land: 150 Years of the Palestine Exploration Fund, Sheffield, UK, Equinox (2019), pp. 212-231

- ^ Marom, Roy (2022). "The Oak Forest of the Sharon (al-Ghaba) in the Ottoman Period: New Insights from Historical- Geographical Studies, Muse 5". escholarship.org. Retrieved 2023-10-06.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 134. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 555

- ^ Grossman, David (2004). Arab Demography and Early Jewish Settlement in Palestine. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. p. 255.

- ^ Karlinsky and Greenwood, 2009, pp. 158–159

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Tulkarem, p. 28

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 57

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 126. Also cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.555

- ^ Morris, 2008, p.164

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, p.556.

- S2CID 144598350.

- ^ Benvenisti, 2002, p.277

- ^ Benvenisti, 2002, p.276

Bibliography

- Ayalon, E. (1982), "Kefar Sava -Nabi Yamin (Tomb of Benjamin)", ESI (Excavations and Surveys in Israel. (English version of Hadashot Arkheologiyot)), 1 p. 63. (Cited in Petersen, 2001)

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Birman, Galit (2006-06-11). "Kefar Sava (East)" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Buchennino, Aviva (2010-05-23). "Kefar Sava, En-Nabi Gamin" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Gorzalczany, Amir (2005-04-07). "Kefar Saba" (117). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karlinsky, Nahum and Naftali Greenwood. "California dreaming: ideology ...." Google Books. 10 August 2009.

- ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ISBN 978-1-84277-761-9.

- Mayer, L.A. (1933). Saracenic Heraldry: A Survey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ---- (2008), 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War, Yale University Press

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. I. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- al-Qawuqji, F. (1972): Memoirs of al-Qawuqji, Fauzi in Journal of Palestine Studies

- "Memoirs, 1948, Part I" in 1, no. 4 (Sum. 72): 27–58., dpf-file, downloadable

- "Memoirs, 1948, Part II" in 2, no. 1 (Aut. 72): 3–33., dpf-file, downloadable

- Wilson, C.W., ed. (c. 1881). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. Vol. 3. New York: D. Appleton. (p.116)

External links

- Welcome to Kafr Saba Palestine Remembered

- Kafr Saba, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 10: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Kafr Saba, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center