Al-Birwa

Al-Birwa

البروة Al-Birweh | ||

|---|---|---|

The former school in al-Birwa, 2019 | ||

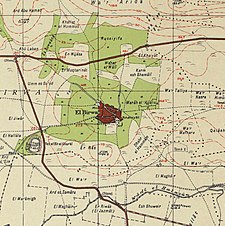

A series of historical maps of the area around Al-Birwa (click the buttons) | ||

Geopolitical entity Mandatory Palestine | | |

| Subdistrict | Acre | |

| Date of depopulation | 11 June 1948[2] or mid-July[3] | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 13,542 dunams (13.5 km2 or 5.2 sq mi) | |

| Population (1945) | ||

| • Total | 1,460[1] | |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces | |

| Current localities | Ahihud,[3] Yas'ur[3][4] | |

Al-Birwa (

The settlement at Al-Birwa was started in the

During

Geography

Al-Birwa stood on a rocky hill overlooking the plain of Acre, with an average elevation of 60 meters above sea level. It was situated at the intersection of two highways—one led to Acre and the other towards

Al-Birwa's total land area consisted of 13,542 dunams (13.42 hectares), of which 59 dunams were built-up areas.[8][9] Cultivable land accounted for 77% of the total land area. Orchards were planted on 1,548 dunams of which 1,500 were used for olive groves, and 8,457 dunams were allotted to grains.[6] The residents of the town sold 536 dunams to Jews, and most of the rest was Arab-owned.[10]

Archaeology

Several excavation has been conducted at the site of al-Birwa after year 2000. Finds included a large building, numerous potsherds from the Late Roman period, a bronze coin from the 1st or 2nd century CE, remains of an ancient olive press, glass vessels such as a wine goblet and bottles dated to the Late Byzantine and Umayyad periods (7th and first half of 8th centuries CE) and an underground water reservoir. A few potsherds from the Crusader and Mamluk periods were also found.[11]

In 2008, the remains of a large olive oil refinery dating from the Byzantine era was uncovered, together with items belonging to a church. The excavators believed that the olive press could be situated inside a Byzantine monastery.[12]

History

Antiquity

The more ancient site, Tel Birwa (variant: Tel Berweh), lies about one mile southwest of the Arab village by the same name, and is said to be a mound measuring 600 paces in circumference at the top, and 75 feet high. The mound abounds with Graeco-Roman potsherds, showing that it was occupied down to Roman times when it was abandoned, as no distinctively Arab pottery could be found there.

Middle Ages

Al-Birwa was mentioned in 1047 CE, during

Ottoman Empire

Al-Birwa came under

In the late 19th century, al-Birwa grew to be a large village, with a well in its southern area.

A population list from about 1887 showed that al-Birwa had about 755 inhabitant, of whom 650 were Muslims and 105 were Christians.[26] In 1888, the Ottomans built an elementary school for boys.[6]

British Mandate

In 1917, during World War I, British forces drove out the Ottomans from Palestine and in 1920, the British Mandate of Palestine was established. In the 1922 British census, al-Birwa had a population of 807, consisting of 735 Muslims and 72 Christians.[27] The Christians were mostly Orthodox with five Anglicans.[28] By the 1931 census, the population had increased to 996, of which 884 were Muslims and 92 were Christians, living in a total of 224 houses.[29] Cement roofs became widely used in al-Birwa in the 1930s, during a time of significant expansion in the village.[6]

A number of al-Birwa's inhabitants participated in the

In the 1945 statistics, al-Birwa's population was 1,460,[8] of which 130 were Christians.[6][1][31] Prominent families and landowners in the village included the Saad, Darwish, Abdullah, Kayyal, Sakkas, al-Wakid, al-Joudi, Najm, al-Dabdoub, Khalid, Akawi, Hissian, Hawash and al-Sheikha families. Socio-economic status in the village was largely determined by land ownership.[32] About 140 residents of the village were tenant farmers who worked for the major landowning Moughrabi, al-Zayyat and Adlabi families.[10] According to intelligence gathered by the Haganah (a Jewish paramilitary organization in Palestine), the traditional, local power brokers of the central Galilee were residents of al-Birwa, who "resolved all conflicts in the nearby villages".[10] Haganah intelligence also reported that al-Birwa's inhabitants were "long-lived, the majority reaching an age of over 100 years".[10]

By the 1940s, al-Birwa had three olive oil presses, a mosque, a church,[6] and approximately 300 houses.[10] In addition to the Ottoman-era boys' school, an elementary school for girls was established in 1943.[6] By this time, many of the inhabitants lost all or part of their lands due to debts, and concurrently, men and women from al-Birwa increasingly worked in public projects, such as road construction and the Haifa oil refinery, or in British military installations, to compensate for lost income.[33] However, the main source of income remained agriculture, and the village's principal crops were olives, wheat, barley, corn, sesame, and watermelons.[6] In 1944–45, residents of the village owned a total of 600 cattle, 3,000 goats and 1,000 chickens.[10] Women, particularly young women from smaller landowning families, participated alongside the men of their family in working the land, while many women from landless families drew income as seasonal workers on other village residents' lands.[34] There were general, gender-based divisions of labor, with women collecting well water, raising livestock, curdling milk, transporting goods to markets in Acre and collecting herbs; men typically plowed and sowed seeds, and both men and women picked olives and harvested crops.[34]

Israel

The Israelis announced that they had battled ALA units in the area, inflicting 100 casualties on 25 June. The New York Times reported that there was fighting in the village for two days and that United Nations (UN) observers were there investigating truce violations. It added that "a small Israeli garrison held al-Birwa prior to the [first] truce", but it fell to ALA troops based in Nazareth who launched a surprise attack. Some residents camped in the outskirts of the village and occasionally managed to enter and gather personal belongings. After the end of the first truce in mid-July, al-Birwa was captured by Israel during Operation Dekel. The ALA fought the Israelis to recapture al-Birwa, but by 18 July, the village was firmly behind Israeli lines.[3]

On 20 August 1948, the Jewish National Fund called for building a settlement on some of al-Birwa's lands, and on 6 January 1949, Yas'ur, a kibbutz, was established there. In 1950, the moshav of Ahihud was inaugurated on the village's western lands. According to Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, one of al-Birwa's schools, two shrines for local sages, and three houses remained standing as of 1982. One of the shrines was domed and built of stone. Most of the structures stood amid cacti, weeds, olive and fig groves, and mulberry trees.[3] Most of al-Birwa's inhabitants fled to nearby Arab towns and villages, including Tamra, Kabul,[36] Jadeidi, Kafr Yasif,[37] and other localities.[36] In Jadeidi the refugees of al-Birwa mostly resided in a neighborhood called al-Barawneh after their village of origin or alternatively al-Kayyali after the Kayyal family, many of whom lived in the neighborhood and one of whom, Afif Kayyal, was elected mayor in the 1990s and in 2003.[38] Some fled to Lebanon, and ended up in the Shatila refugee camp, in the outskirts of Beirut, where Palestinian historian Nafez Nazzal interviewed them in 1973.[39] Among the refugees of al-Birwa was Mahmoud Darwish, who was born in the village in 1941 and lived part of his childhood there.[40]

In 1950,

Al-Birwa is among the Palestinian villages for which commemorative Marches of Return have taken place, typically as part of Nakba Day, such as the demonstrations organized by the Association for the Defence of the Rights of the Internally Displaced.[44]

See also

- Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 4

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xvii, village #89. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- ^ a b c d e Khalidi 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xxi, settlement #47, January 1949

- ^ Abu Raya, 2020, Ahihud (East)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Khalidi 1992, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Meari 2010, p. 122.

- ^ a b Hadawi 1970, p. 40.

- ^ Hadawi 1970, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e f g Benvenisti 2000, p. 317.

- ^ Porat, 2010, Ahihud

- ^ An ancient complex for Producing Oil was discovered

- ^ Albright (1921/1922), p. 27

- .

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War (2.18.9). As pointed out by Simchoni, Jacob N. (1968). The History of the War of the Jews with the Romans (in Hebrew). Ramat-Gan: Masada. p. 565., the translators of The Jewish War in 2.18.9 and in 3.3.1. have, in both cases, transcribed the Greek word Cabul (Gr. Χαβουλών), used there for this city in the original text, as Zabulon.

- ^ Le Strange 1890, p. 423.

- ^ Delaville Le Roulx 1883, p. 184; cited in Clermont-Ganneau, 1888, pp. 309–310; cited in Röhricht 1893, RRH, p. 319, No. 1210.

- ^ Barag, Dan (1979). "A new source concerning the ultimate borders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem". Israel Exploration Journal. 29: 197–217.

- ^ Holt 1986, p. 103.

- ^ a b Hütteroth and Abdulfattah 1977, p. 190, quoted in Khalidi 1992, p. 9.

- ^ Karmon 1960, p. 162 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Conder & Kitchener 1881, p. 270.

- ^ van de Velde 1858, p.223.

- ^ Robinson 1856, p. 630.

- ^ Guérin 1880, pp. 432–433.

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 176

- ^ Barron 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Acre, p. 37.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 50.

- ^ Mills 1932, p. 100.

- ^ Meari 2010, p. 132.

- ^ "Non-Jewish Population within the Boundaries Held by the Israel Defence Army on 1:5:49 in Accordance with the Palestine Government Village Statistics, April 1945" (PDF). United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine. 1949. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2012.

- ^ Meari 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Meari 2010, p. 125.

- ^ a b Meari 2010, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Nazzal 1978, pp.65–70, quoted in Khalidi 1992, p. 10.

- ^ a b Bokae'e, Nihad (February 2003). "Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures" (PDF). Badil. Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights.

- ^ Meari 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Boqa'i 2005, pp. 80, 85.

- ^ Nazzal 1978, pp. 65–70

- ^ Torstrick 2004, p. 64.

- .

- ^ Kacowicz & Lutomski 2007, p. 139.

- .

- ^ Charif, Maher. "Meanings of the Nakba". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

Sources

- Abu Raya, Rafeh (28 May 2020). "Ahihud (East)" (132). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Albright, W.F. (1922). "Contribution to the Historical Geography of Palestine". Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 2–3: 1–46.

- Barag, Dan (1979). "A new source concerning the ultimate borders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem". JSTOR 27925726.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 978-0-520-21154-4.

- Boqa'i, Nihad (2005). "Patterns of Internal Displacement, Social Adjustment and the Challenge of Return". In Masalha, Nur (ed.). Catastrophe Remembered: Palestine, Israel and the Internal Refugees. New York: Zed Books. pp. 73–112. ISBN 1-84277-622-3.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1888). Recueil d'archéologie orientale (in French). Vol. 1. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Delaville Le Roulx, Joseph (1883). Les archives, la bibliothèque et le trésor de l'Ordre de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem à Malte (in French and Latin). Paris: E. Leroux.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm (1986). The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 151. ISBN 9781317871521.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-920405-41-4.

- Josephus (1961). The Jewish War. Vol. 2. Translated by H. St. J. Thackeray. London: Loeb Classical Library (Books I-III).

- Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel (2007). Population Resettlement in International Conflicts: A Comparative Study. Lanham, Maryland: ISBN 978-0-7391-1607-4.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3–4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-88728-224-9.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E. Editor (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas (PDF). Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Meari, Lena (2010). Kanaaneh, Rhoda Ann; Nusair, Isis (eds.). The Roles of Palestinian Peasant Women: The Case of al-Birweh Village, 1930–1960. ISBN 978-1-4384-3271-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Nazzal, Nafez (1978). The Palestinian Exodus from Galilee 1948. Beirut: The Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 9780887281280.

- Porat, Leea; Getzov, Nimrod (7 February 2010). "Ahihud". Israel Antiquities Authority.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 9780837002514.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Torstrick, Rebecca L. (30 June 2004). Culture and Customs of Israel (1 ed.). Westport, Conn: ISBN 978-0313320910.

- Velde, van de, C.W.M. (1858). Memoir to Accompany the Map of the Holy Land. Gotha: Justus Perthes.

External links

- Welcome To al-Birwa

- al-Birwa, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 5: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Fifth Procession of Return by ADRID in al-Birweh, 2002

- Fifth Procession of Return by ADRID in al-Birweh[usurped], Yosefa Mekaitun, 2002, Zochrot

- Inside a Palestinian refugee camp, Martin Asser BBC, 14 May 2008. Interview with Muhammad Diab from al-Birwa, now refugee in the Shatila refugee camp, Lebanon.