Sabalan, Safad

Sabalan

سبلان | ||

|---|---|---|

Village | ||

| Etymology: Neby Sebelan; the prophet Sebelan[1] | ||

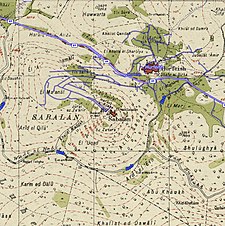

A series of historical maps of the area around Sabalan, Safad (click the buttons) | ||

Geopolitical entity Mandatory Palestine | | |

| Subdistrict | Safad | |

| Date of depopulation | October 30, 1948[3] | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 1,798 dunams (1.798 km2 or 444 acres) | |

| Population (1945) | ||

| • Total | 70[2] | |

| Current Localities | None | |

Sabalan (

History

According to Muhammad Fahour, a former resident of Sabalan, the village was founded during the French campaign in Syria (1798–1801) when Suleiman al-Bahiri, an Egyptian officer from Egyptian, decided to escape to Palestine after Napoleon declared war on Egypt. Following a recurrent dream he had, he decided to settle on Mount Sabalan.[5]

In 1881, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described 'Neby Sebelan' as "a village, built of stone, surrounding the tomb of the Neby Sebalan; containing about 100 Moslems; on top of high hill, with figs, olives, and arable land. There are four good springs to the east, besides cisterns."[6][7] Some believe Sabalan is supposed to be Zebulun, the son of Jacob, while others claim he was a da'i ("missionary") who joined the Druze religion and helped promote it in the region.[8] Archaeological artifacts, namely rock-cut tombs are located near the tomb.[9] A population list from about 1887 showed 'Nebi Abu Sebalan' to have about 75 inhabitants; all Muslims.[10]

British Mandate era

In the British Mandate period, it had a circular plan with most of its houses being closely clustered together. Because of the steep slopes that surrounded Sabalan, the village was only able to expand on its northwestern end.[7] Although the tomb of Nabi Sabalan was sacred to the Druze,[9] at the centre of the village stood a mosque.[7]

In the 1922 census of Palestine Sabalan had a population of 68; all Muslims,[11] increasing in the 1931 census, to 94 Muslims, living in 18 houses.[12]

By 1945 the population was 70 Muslims,[2] and the village consisted of 1,798 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey.[4] Of this, a total of 421 dunams were used for cereals; 144 dunams were irrigated or used for plantations,[13] while a 14 dunams were built-up (urban) areas.[14]

1948, aftermath

On October 30, 1948, during the

Today, the lands of the village, including the holy shrine, were annexed to the Druze town of Hurfeish. A neighborhood for released soldiers was built there.

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 92

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 10

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xvii, village #62. Also gives cause of depopulation as "?"

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 71

- ^ "Remembering Sabalan". Zochrot.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 199

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p.489.

- ^ a b Swayd, 2006, p.140.

- ^ a b c d Khalidi, 1992, p. 490

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 191

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Safad, p. 41

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 110

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 120

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 170

- ^ Firro, 1999, p.182.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Firro, Kais (1999). The Druzes in the Jewish state: a brief history. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11251-0.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Swayd, Sami S. (2006). Historical dictionary of the Druzes. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8108-5332-9.

External links

- Welcome To Sabalan

- Sabalan, Zochrot

- Saabalan, Villages of Palestine

- Sabalan, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- The story of Sabalan, 24/10/2008, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4: IAA, Wikimedia commons