Vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson

Portrait by Charles Willson Peale c. 1791 | |

| Vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801 | |

President | |

|---|---|

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Democratic-Republican Party[a] |

| Election | 1796 |

|

| |

The vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson lasted from 1797 to 1801, and was the second

Jefferson was born into the Colony of Virginia's planter class, dependent on slave labor. During the American Revolution, Jefferson represented Virginia in the Second Continental Congress, which unanimously adopted the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson's advocacy for individual rights, including freedom of thought, speech, and religion, helped shape the ideological foundations of the revolution and inspired the Thirteen Colonies in their revolutionary fight for independence, which culminated in the establishment of the United States as a free and sovereign nation.

Jefferson served as the second governor of revolutionary Virginia from 1779 to 1781. In 1785, Congress appointed Jefferson U.S. minister to France, where he served from 1785 to 1789. President Washington then appointed Jefferson the nation's first United States Secretary of State, where he served from 1790 to 1793. In 1792, Jefferson and political ally James Madison organized the Democratic-Republican Party to oppose the Federalist Party during the formation of the nation's First Party System. Jefferson and Federalist John Adams became both personal friends and political rivals.

In the

Election of 1796

With incumbent president George Washington having refused a third term in office, the 1796 election became the first U.S. presidential election in which political parties competed for the presidency. The Federalists coalesced behind Adams and the Democratic-Republicans supported Jefferson, but each party ran multiple candidates. Under the electoral rules in place prior to the Twelfth Amendment, the members of the Electoral College each cast two votes, with no distinction made between electoral votes for president and electoral votes for vice president. The individual with the votes of a majority of electors became president, and the runner-up became vice president. If there was a tie for first place or no person won a majority, the House of Representatives would hold a contingent election. Also, if there were a tie for second place, the vice presidency, the Senate would hold a contingent election to break the tie.

The campaign was a bitter one, with Federalists attempting to identify the Democratic-Republicans with the violence of the French Revolution[1] and the Democratic-Republicans accusing the Federalists of favoring monarchism and aristocracy. Republicans sought to associate Adams with the policies developed by fellow Federalist Alexander Hamilton during the Washington administration, which they declaimed were too much in favor of Great Britain and a centralized national government. In foreign policy, Republicans denounced the Federalists over the Jay Treaty, which had established a temporary peace with Great Britain. Federalists attacked Jefferson's moral character, alleging he was an atheist and that he had been a coward during the American Revolutionary War. Adams supporters also accused Jefferson of being too pro-France; the accusation was underscored when the French ambassador embarrassed the Republicans by publicly backing Jefferson and attacking the Federalists right before the election.[2] Despite the hostility between their respective camps, neither Adams nor Jefferson actively campaigned for the presidency.[3][2]

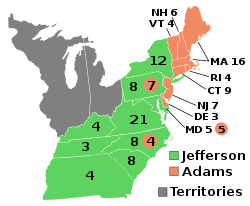

In the presidential campaign of 1796, Jefferson lost the electoral college vote to Federalist John Adams 71–68. He did, however, receive the second-highest number of votes and, under the electoral laws at the time, was elected as vice president. Adams was elected president with 71 electoral votes, one more than was needed for a majority. He won by sweeping the electoral votes of New England and winning votes from several other swing states, especially the states of the Mid-Atlantic region. Jefferson received 68 electoral votes and was elected vice president. Former governor Thomas Pinckney of South Carolina, a Federalist, finished with 59 electoral votes, while Senator Aaron Burr, a Democratic-Republican from New York, won 30 electoral votes. The remaining 48 electoral votes were dispersed among nine other candidates. Several electors cast one vote for a Federalist candidate and one for a Democratic-Republican. The election marked the formation of the First Party System, and established a rivalry between Federalist New England and the Democratic-Republican South, with the middle states holding the balance of power (New York and Maryland were the crucial swing states, and between them only voted for a loser once between 1789 and 1820).[4]

Vice presidency (1797-1801)

As presiding officer of the United States Senate, Jefferson assumed a more passive role than his predecessor, John Adams. He allowed the Senate to freely conduct debates and confined his participation to procedural issues, which he called an "honorable and easy" role.[5] Jefferson previously studied parliamentary law and procedure for 40 years, making him qualified to serve as presiding officer. In 1800, he published his assembled notes on Senate procedure as A Manual of Parliamentary Practice.[6] He cast only three tie-breaking votes in the Senate.

In four confidential talks with French consul Joseph Létombe in the spring of 1797, Jefferson attacked Adams, predicting that his rival would only serve one term. He also encouraged France to invade England, and advised Létombe to stall any American envoys sent to Paris.[7] This toughened the tone that the French government adopted toward the Adams administration. After Adams's initial peace envoys were rebuffed, Jefferson and his supporters lobbied for the release of papers related to the incident, called the XYZ Affair after the letters used to disguise the identities of the French officials involved.[8] But the tactic backfired when it was revealed that French officials had demanded bribes, rallying public support against France. The U.S. began an undeclared naval war with France known as the Quasi-War.[9]

During the Adams presidency, the Federalists rebuilt the military, levied new taxes, and enacted the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson believed these laws were intended to suppress Democratic-Republicans, rather than prosecute enemy aliens, and considered them unconstitutional.[10] To rally opposition, he and James Madison anonymously wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, asserting that the federal government had no right to exercise powers not specifically delegated to it by the states.[11] The resolutions followed the "interposition" approach of Madison, that states may shield their citizens from federal laws that they deem unconstitutional. Jefferson advocated nullification, allowing states to entirely invalidate federal laws.[12][b] He warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold", the Alien and Sedition Acts would "drive these states into revolution and blood".[14]

Biographer Ron Chernow contends that "the theoretical damage of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions was deep and lasting, and was a recipe for disunion", and contributed to the outbreak of the American Civil War and later events.[15] Washington was so appalled by the resolutions that he told Patrick Henry that, if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", the resolutions would "dissolve the union or produce coercion."[16] Jefferson had always admired Washington's leadership skills but felt that his Federalist party was leading the country in the wrong direction. He decided not to attend Washington's funeral in 1799 because of acute differences with him while serving as secretary of state.[17]

List of tie-breaking votes cast

This section needs expansion with: tie breaking votes cast. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

Election of 1800

Jefferson ran for president against John Adams again in 1800. Adams' campaign was weakened by unpopular taxes and vicious Federalist infighting over his actions in the Quasi-War.[18] Democratic-Republicans pointed to the Alien and Sedition Acts and accused the Federalists of being secret pro-Britain monarchists. Federalists, in turn, charged that Jefferson was a godless libertine beholden to the French.[19] UCLA history professor Joyce Appleby described the 1800 presidential election as "one of the most acrimonious in the annals of American history".[20]

The Democratic-Republicans ultimately won more electoral college votes, due in part to the electors that resulted from the addition of three-fifths of the South's slaves to the population calculation under the

The win led to Democratic-Republican celebrations throughout the country.

The transition proceeded smoothly, marking a watershed in American history. Historian Gordon S. Wood writes that, "it was one of the first popular elections in modern history that resulted in the peaceful transfer of power from one 'party' to another."[23]

Presidency

Relationship with vice president Aaron Burr

Following the 1801 electoral deadlock, Jefferson's relationship with his vice president, Aaron Burr, rapidly eroded. Jefferson suspected Burr of seeking the presidency for himself, while Burr was angered by Jefferson's refusal to appoint some of his supporters to federal office. Burr was dropped from the Democratic-Republican ticket in 1804 in favor of charismatic George Clinton.

The same year, Burr was soundly defeated in his bid to be elected New York governor. During the campaign, Alexander Hamilton made publicly callous remarks regarding Burr's moral character.[27] Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, held on July 11, 1804. In the duel, Burr mortally wounded Hamilton, who died the following day. Burr was subsequently indicted for Hamilton's murder, causing him to flee to Georgia, even though he remained president of the U.S. Senate during Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase's impeachment trial.[28] Both indictments quietly died and Burr was not prosecuted.[29]

Jefferson attempted to try former vice president Burr with treason over the Burr conspiracy, but Burr was acquitted in multiple trials.

Legacy

Historical reputation

Jefferson is seen as an icon of individual liberty, democracy, and

Memorials and honors

Jefferson has been memorialized with buildings, sculptures,

The Jefferson Memorial was dedicated in Washington, D.C., in 1943, on the 200th anniversary of Jefferson's birth. The interior of the memorial includes a 19-foot (6 m) statue of Jefferson by Rudulph Evans and engravings of passages from Jefferson's writings. Most prominent among these passages are the words inscribed around the Jefferson Memorial: "I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man", a quote from Jefferson's September 23, 1800, letter to Benjamin Rush.[36]

In October 2021, in response to lobbying, the New York City Public Design Commission voted unanimously to remove the plaster model of the statue of Jefferson that currently stands in the United States Capitol rotunda from the chamber of the New York City Council, where it had been for more than a century, due to him fathering children with people he enslaved.[37] The statue was taken down the next month.[38]

-

Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.

-

Jefferson Memorial statue by Rudulph Evans, 1947

-

Mount Rushmore (Shrine of Democracy) by Gutzon Borglum. From left to right: Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln.

-

Jefferson has been featured on theU.S. two-dollar billfrom 1928 to 1966 and since 1976.

-

Jefferson has been depicted on the U.S. nickel since 1938.

Writings

- A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774)

- Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms (1775)

- Declaration of Independence (1776)

- Memorandums taken on a journey from Paris into the southern parts of France and Northern Italy, in the year 1787

- Notes on the State of Virginia (1781)

- Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States A report submitted to Congress (1790)

- "An Essay Towards Facilitating Instruction in the Anglo-Saxon and Modern Dialects of the English Language" (1796)

- Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States (1801)

- Autobiography (1821)[39]

- Jefferson Bible, or The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth

See also

Notes

- ^ Most commonly referred to as the Republican Party at the time

- ^ Jefferson's Kentucky draft said: "where powers are assumed which have not been delegated, a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy: that every State has a natural right in cases not within the compact, (casus non fœderis) to nullify of their own authority all assumptions of power by others within their limits."[13]

- ^ This electoral process problem was addressed by the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1804, which provided separate votes for presidential and vice-presidential candidates.[23]

Citations

- ^ Presidential Election of 1796, retrieved on November 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "John Adams: Campaigns and Elections—Miller Center". millercenter.org. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ "Inside America's first dirty presidential campaign, 1796 style". Constitution Daily. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey L. Pasley, The First Presidential Contest: 1796 and the Founding of American Democracy (2013)

- ^ Meacham, 2012, p. 305.

- ^ Bernstein, 2003, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Elkins, 1994, p. 566.

- ^ Chernow, 2004, p. 550.

- ^ Meacham, 2012, p. 312.

- ^ Tucker, 1837, v. 2, p. 54.

- ^ Wood, 2010, pp. 269–271.

- ^ Meacham, 2012, p. 318.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, Resolutions Relative to the Alien and Sedition Acts, 1798

- ^ Onuf, 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Chernow, 2004, p. 574.

- ^ Chernow, 2004, p. 587.

- ^ Meacham, 2012, p. 323.

- ^ McCullough, 2001, p. 556; Bernstein, 2003, pp. 126–128.

- ^ McCullough, 2001, pp. 543–544.

- ^ Appleby, 2003, pp. 27–28.

- ^ The Corrupt Bargain, Eric Foner, The London Review of Books, Vol. 42 No. 10, May 21, 2020, accessed November 3, 2020

- ^ Tucker, 1837, v. 2, p. 75; Wood, 2010, p. 278.

- ^ a b c d Wood, 2010, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Meacham, 2012, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Ferling, 2004, p. 208.

- ^ Meacham, 2012, pp. 337–338.

- ^ Chernow, 2004, p. 714.

- ^ Wood, 2010, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Banner 1974, p. 34.

- ^ Peterson, 1960, pp. 5, 67–69, 189–208, 340.

- ^ Appleby, 2003, p. 149.

- ^ Meacham, 2012, p. xix.

- ^ SRI, 2010.

- ^ Brookings, 2015

- ^ NPS: Mt. Rushmore

- ^ Peterson, 1960, p. 378.

- ^ O'Brien, Brendan (October 19, 2021). "Thomas Jefferson Statue to be Removed from New York City Council Chamber". Reuters. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ Luscombe, Richard (November 23, 2021). "New York city hall removes Thomas Jefferson statue". The Guardian. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- )

Works cited

Scholarly studies

- Adams, Herbert Baxter (1888). Thomas Jefferson and the University of Virginia. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Alexander, Leslie (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History (American Ethnic Experience). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851097692.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0684811079.

- Andresen, Julie (2006). Linguistics in America 1769–1924: A Critical History. ISBN 978-1134976119.

- Andrews, Stuart. "Thomas Jefferson and the French Revolution" History Today (May 1968), Vol. 18 Issue 5, pp. 299–306.

- Appleby, Joyce Oldham (2003). Thomas Jefferson: The American Presidents Series: The 3rd President, 1801–1809. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805069242.

- Bailey, Jeremy D. (2007). Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-1139466295.

- Banner, James M. Jr. (1974). C. Vann Woodward (ed.). Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct. Delacorte Press Dell Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 978-0440059233.

- Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian persuasion: evolution of a party ideology (1978) online

- Bassani, Luigi Marco (2010). Liberty, State & Union: The Political Theory of Thomas Jefferson. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0881461862.

- Bear, James Adam (1967). Jefferson at Monticello. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813900223.

- —— (1974). "The Last Few Days in the Life of Thomas Jefferson". Magazine of Albemarle County History. 32: 77.

- ISBN 978-0195181302.

- —— (2004). The Revolution of Ideas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195143683.

- Berry, Trey; Beasley, Pam; Clements, Jeanne (2006). The Forgotten Expedition, 1804–1805: The Louisiana Purchase Journals of Dunbar and Hunter. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0807131657.

- Bober, Natalie (2008). Thomas Jefferson: Draftsman of a Nation. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813927329.

- Boles, John B. (2017). Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty. Basic Books,626 pages. ISBN 978-0465094691.

- Brodie, Fawn (1974). Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393317527.

- Bowers, Claude (1945). The Young Jefferson 1743–1789. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Burstein, Andrew (2006). Jefferson's Secrets: Death and Desire at Monticello. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465008131.

- ——; Isenberg, Nancy (2010). Madison and Jefferson. Random House. ISBN 978-1400067282.

- ISBN 978-1594200090.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1926). Chinard, Gilbert (ed.). The Commonplace Book of Thomas Jefferson: A Repertory of His Ideas on Government, with an Introduction and Notes by Gilbert Chinard, Volume 2. Princeton University Press. )

- Cogliano, Francis D (2008). Thomas Jefferson: Reputation and Legacy. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748624997.

- Cooke, Jacob E. (1970). "The Compromise of 1790". William and Mary Quarterly. 27 (4): 523–545. JSTOR 1919703.

- Cunningham, Vinson (December 28, 2020). "What Thomas Jefferson Could Never Understand About Jesus". newyorker.com. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- Crawford, Alan Pell (2008). Twilight at Monticello: The Final Years of Thomas Jefferson. Random House Digital. ISBN 978-1400060795.

- Davis, David Brion (1999). The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199880836.

- )

- Earle, Edward Mead (1927). "American Interest in the Greek Cause, 1821–1827". The American Historical Review. 33 (1): 44–63. JSTOR 1838110.

- Elkins, Stanley M.; McKitrick, Eric L. (1993). The Age of Federalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195068900.

- ISBN 978-0679444909. online free

- —— (2000). Thomas Jefferson: Genius of Liberty. Viking Studio. ISBN 978-0670889334.

- —— (2003). Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1400077687.

- —— (2008). American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies in the Founding of the Republic. Random House LLC. ISBN 978-0307263698.

- ISBN 978-0195134094.

- —— (2004). Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195167719.

- JSTOR 3123523.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2006). The Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties A-F Index. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1135947040.

- Finkelman, Paul (April 1994). "Thomas Jefferson and Antislavery: The Myth Goes On" (PDF). The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 102, no. 2. Virginia Historical Society. pp. 193–228.

- Foster, Eugene A.; et al. (November 5, 1998). "Jefferson fathered slave's last child". Nature. 396 (6706): 27–28. S2CID 4424562.

- Frawley, William J., ed. (2003). "International Encyclopedia of Linguistics: 4-Volume Set". International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195139778.

- Freehling, William W. (2005). Levinson, Sanford; Sparrow, Bartholomew H. (eds.). The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion, 1803–1898 The Louisiana Purchase and the Coming of the Civil War. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 69–82. ISBN 978-0742549838.

- ISBN 978-0521867313.

- Gish, Dustin, and Daniel Klinghard. Thomas Jefferson and the Science of Republican Government: A Political Biography of Notes on the State of Virginia (Cambridge University Press, 2017) excerpt.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2006). The Wars of the Barbary Pirates: To the Shores of Tripoli – The Rise of the US Navy and Marines. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1846030307.

- Golden, James L.; Golden, Alan L. (2002). Thomas Jefferson and the Rhetoric of Virtue. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742520806.

- ISBN 978-0813916989.

- —— (2008). The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393064773.

- Gordon-Reed, Annette (February 20, 2020). "Thomas Jefferson's Vision of Equality Was Not All-Inclusive. But It Was Transformative". Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- Greider, William (2010). Who Will Tell the People. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1439128749.

- Halliday, E. M. (2009). Understanding Thomas Jefferson. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0060197933.

- Hamelman, Steven (January 1, 2002). "Autobiography and Archive: Franklin, Jefferson, and the Revised Self". Midwest Quarterly.

- Harrison, John Houston (1935). Settlers by the Long Grey Trail: Some Pioneers to Old Augusta County, Virginia, and Their Descendants of the Family of Harrison and Allied Lines. Genealogical Publishing Com. )

- Hart, Charles Henry (1899). Browere's Life Masks of Great Americans. De Vinne Press for Doubleday and McClure Company.

- Hayes, Kevin J. (2008). The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195307580.

- Hellenbrand, Harold (1990). The Unfinished Revolution: Education and Politics in the Thought of Thomas Jefferson. Associated University Presse. ISBN 978-0874133707.

- Helo, Ari (2013). Thomas Jefferson's Ethics and the Politics of Human Progress: The Morality of a Slaveholder. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107435551.

- Hendricks, Nancy (2015). America's First Ladies. ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1610698832.

- Herring, George C. (2008). From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199743773.

- Hogan, Pendleton (1987). The Lawn: A Guide to Jefferson's University. University Press of Virginia. ISBN 978-0813911090.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2009). Making the American Self: Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199740796.

- Hyland, William G (2009). In Defense of Thomas Jefferson: The Sally Hemings Sex Scandal. Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 978-0890890851.

- Jacavone, Jared (2017). The Paid Vote: America's Neutrality During the Greek War for Independence (MA thesis). University of Rhode Island. .

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. (1999). Thomas Jefferson: Westward the Course of Empire. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0842026307.

- Kaufman, Will; Macpherson, Heidi Slettedahl (2005). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- Keyssar, Alexander (2009). The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465010141.

- ISBN 978-0679454922.

- Malone, Dumas, ed. (1933). "Jefferson, Thomas". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 10. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 17–35.

- Malone, Dumas. Jefferson (6 vol. 1948–1981)

- —— (1948). Jefferson, The Virginian.

- —— (1951). Jefferson and the Rights of Man. Jefferson and His Time. Vol. 2. Little Brown.

- —— (1962). Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty. )

- —— (1970). Jefferson the President: First Term, 1801–1805. Jefferson and His Time. Vol. 4. Little Brown.

- —— (1974). Jefferson the President: Second Term, 1805–1809. OCLC 1929523.

- —— (1981). The Sage of Monticello. ISBN 978-0316544788.

- Mapp, Alf J. (1991). Jefferson: Passionate Pilgrim. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0517098882.

- Mayer, David N. (1994). The Constitutional Thought of Thomas Jefferson (Constitutionalism and Democracy). University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813914855.

- McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1471104527.

- McDonald, Robert M. S. (2004). Thomas Jefferson's Military Academy: Founding West Point. Jeffersonian America. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813922980.

- McEwan, Barbara (1991). Thomas Jefferson, Farmer. McFarland. ISBN 978-0899506333.

- ISBN 978-0679645368.

- —— (2013). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (Paperback). Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0812979480.

- Miller, John Chester (1980). The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0452005303.

- Miller, Robert J. (2008). Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, and Manifest Destiny. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803215986.

- Mott, Frank Luther. (1943) Jefferson and the press (LSU Press) online

- Onuf, Peters S. (2000). Jefferson's Empire: The Language of American Nationhood. U of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813922041.

- —— (2007). The Mind of Thomas Jefferson. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813926117.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (1960). The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. University of Virginia Press. )

- —— (1970). Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation; a Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195000542.

- —— (2002). "Thomas Jefferson". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (7th ed.). Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 39–56.

- Phillips, Julieanne (1997). "Northwest Ordinance (1787)". In ISBN 978-0874368857.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1994). Thomas Jefferson: A Life. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0060976170., popular history; weak after 1790.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1996). "Thomas Jefferson Takes A Vacation". American Heritage. Vol. 47, no. 4.

- Rodriguez, Junius (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: a historical and geographical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576071885.

- Stewart, John J. (1997). Thomas Jefferson: Forerunner to the Restoration. Cedar Fort. ISBN 978-0-88290-605-8.

- Sheehan, Bernard (1974). Seeds of Extinction: Jeffersonian Philanthropy and the American Indian. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393007169.

- Scythes, James (2014). Tucker, Spencer C. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Early American Republic, 1783–1812 A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598841565.

- Shuffelton, Frank (1974). "Introduction". In Jefferson, Thomas. (ed.). Notes on the State of Virginia. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140436679.

- Smith, Robert C. (2003). Encyclopedia of African American Politics. Infobase Publishing, 433 pages. ISBN 978-1438130194.

- Tucker, George(1837). The Life of Thomas Jefferson, Third President of the United States; 2 vol. Carey, Lea & Blanchard.

- —— (1990). Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson. Cogliano Press. ISBN 978-0198022763.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., ed. (2006). Biographical Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court: The Lives and Legal Philosophies of the Justices. CQ Press. ISBN 978-1452267289.

- Wiencek, Henry (2012). Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and his slaves. Macmillan.

- ISBN 978-0393058208.

- Wilson, Steven Harmon (2012). The U.S. Justice System: Law and constitution in early America. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598843040.

- ISBN 978-1594200939.

- —— (2010). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195039146.

- —— (2011). The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594202902.

Thomas Jefferson Foundation sources

- "American Philosophical Society". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Coded Messages". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "Embargo of 1807". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "I Rise with the Sun". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "Italy – Language". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "James Madison". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "Jefferson's Antislavery Actions". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Jefferson's Religious Beliefs". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- "Maria Cosway (Engraving)". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "Minority Report of the Monticello Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Monticello construction chronology". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- "Monticello (House) FAQ – Who built the house?". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- "Nailery". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "President Jefferson and the Indian Nations". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "Public Speaking". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Quotations on Slavery and Emancipation". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings – Conclusions". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Sale of Monticello". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- "Slave Dwellings". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- "Slavery at Monticello FAQ – Property". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Slavery at Monticello FAQ – Work". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Spanish Language". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson: A Brief Biography". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson and Slavery". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson's Enlightenment and American Indians". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson's Religious Beliefs". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

Primary sources

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, – the Princeton University Press edition of the correspondence and papers; vol 1 appeared in 1950; vol 41 (covering part of 1803) appeared in 2014.

- Jefferson, Thomas (November 10, 1798). "Thomas Jefferson, Resolutions Relative to the Alien and Sedition Acts". The Founder's Constitution. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- Thomas, Jefferson (1914). Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson 1743–1790. G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- "Thomas Jefferson". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1900). The Life and Writings of Thomas Jefferson. pp. 265–266.

- —— (1853). Notes on the State of Virginia. J.W. Randolph. (Note: This was Jefferson's only book; numerous editions)

- —— (1977). The Portable Thomas Jefferson. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1101127667.

- Yarbrough, Jean M.; Jefferson, Thomas (2006). The Essential Jefferson. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-1603843782.

Web site sources

- "Gathering Voices: Thomas Jefferson and Native America". American Philosophical Society. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson to Horatio G. Spafford, 17 March 1814". U.S. Government: National Archives. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- "American President: A Reference Resource". University of Virginia: Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- Barger, Herbert (October 15, 2008). "The Jefferson-Hemings DNA Study". Jefferson DNA Study Group. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- "Carving History". Mount Rushmore National Memorial. National Park Service. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- De Witte, Melissa (July 1, 2020). "When Thomas Jefferson penned 'all men are created equal,' he did not mean individual equality, says Stanford scholar". StandfordReport. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- Finkelman, Paul (November 30, 2012). "The Monster of Monticello". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- Haimann, Alexander T. (May 16, 2006). "5-cent Jefferson". Arago, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Jefferson's library". Library of Congress. April 24, 2000. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "Jefferson Nickel". U.S. Mint. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Jefferson's Vision of the Academical Village". University of Virginia. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- "Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson". National Archives.

- Roberts, Gary Boyd (April–May 1993). "The Royal Descents of Jane Pierce, Alice and Edith Roosevelt, Helen Taft, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Barbara Bush". American Ancestors. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (February 13, 2015). "Measuring Obama against the great presidents". Brookings Institution. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- "The Jefferson Hemings Controversy – Report of The Scholars Commission: Summary" (PDF). Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society. 2011 [2001]. pp. 8–9, 11, 15–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- "Siena Poll: American Presidents". Siena Research Institute. July 6, 2010. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- "Thomas Jefferson: Biography". National Park Service. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "The Thomas Jefferson Papers Timeline: 1743–1827". Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- "Thomas Jefferson Presidential $1 Coin". U.S. Mint. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "U.S. Currency: $2 Note". U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth". 1820. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- "Bookquick/"The Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, 1743–1790" | Penn Current". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- Konig, David T. "Jefferson Thomas and the Practice of_Law, Three cases". Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- "The Burr Conspiracy". PBS American Experience. 2000. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- Wilson, Douglas L. (1992). "Thomas Jefferson and the Issue of Character". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- "Thomas Jefferson's descendants unite over a troubled past". CBS News. February 14, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings A Brief Account". monticello.org. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Peter, Carlson (September 27, 2017). "The Bible According to Thomas Jefferson". historynet.com. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

External links

- Scholarly coverage of Jefferson at Miller Center, U of Virginia

- United States Congress. "Vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson (id: J000069)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive at the Massachusetts Historical Society

- Thomas Jefferson collection at the University of Virginia Library

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, subset of Founders Online from the National Archives

- Jefferson, Thomas (1774). Summary View of the Rights of British America. Printed by Clementina Rind – via World Digital Library.

- The Thomas Jefferson Hour, a radio show about all things Thomas Jefferson The Thomas Jefferson Hour

- "The Papers of Thomas Jefferson". Avalon Project.

- Works by Vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson at the Internet Archive

- Works by Vice presidency of Thomas Jefferson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts and Letters".

- "Thomas Jefferson's Family: A Genealogical Chart". Jefferson Quotes & Family Letters.