Bayt Nattif: Difference between revisions

81,070 edits again, remove material which do not mention this place. Keep "proposed 1947 UN Partition Plan" |

Extended confirmed users 54,591 edits |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===Early history=== |

|||

In a Judeo-historic context, the land whereon lies Bayt Nattif and the adjacent cities of [[Adullam]], [[Socho]], Yarmuth, [[Azekah]] (now ruins) and [[Zanoah|Zenoah]] fell to the tribe of Judah in ''circa'' 1258 BCE, when the country's borders were delineated and divided by lot to the 12 tribes of Israel, excluding the tribe of Levi.<ref>[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/8907-joshua-book-of Jewish Encyclopedia: Joshua: Book of]; Joshua 15: 33–36; year of conquest based on ''[[Seder Olam Rabbah]]'' (ed. M.D. Yerushalmi), chapter 11, Jerusalem 1971, pp. 39–40</ref> Subsequently, during the post-[[Canaan|Canaanite]] era, the region was settled by families of the [[Tribe of Judah]], who then took possession of the cities and rebuilt them.<ref>Younger, p. 183</ref> Such was the condition until the Israelite tribes were expelled from the land under Nebuchadnezzar's army in the 5th century BCE. |

|||

Bayt Nattif was known under the [[Roman Empire|Romans]] as ''Bayt Letepha''.<ref name=Khalidi211/> According to [[Josephus]], the city was sacked under Vespasian and Titus, during the first Jewish uprising against Rome.<ref>Josephus, ''De Bello Judaico'' (Wars of the Jews) iv.viii.1.</ref> |

Bayt Nattif was known under the [[Roman Empire|Romans]] as ''Bayt Letepha''.<ref name=Khalidi211/> According to [[Josephus]], the city was sacked under Vespasian and Titus, during the first Jewish uprising against Rome.<ref>Josephus, ''De Bello Judaico'' (Wars of the Jews) iv.viii.1.</ref> |

||

| Line 62: | Line 65: | ||

The Israeli Air Force bombed the area of Bayt Nattif on October 19, 1948, which started panic flights from Bayt Nattif and [[Bayt Jibrin]].<ref>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA468 468], note #32 in Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA494 494]</ref> Bayt Nattif was depopulated during the [[1948 Arab-Israeli War]] on October 21, 1948 under ''[[Operation Ha-Har]]'', by the Fourth Battalion of the [[Har'el Brigade]].<ref name=Khalidi211/><ref name=Morris2008p329>Morris, 2008, p. 329</ref><ref>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA462 462]</ref> There are conflicting reports about its conquest, one [[Palmah]] report says that the villagers "fled for their lives",<ref name=Morris466>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA466 466] note #14, in Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA493 493]. "Book of the Palmah, II" pp. 646, 652</ref> while a Haganah report says that the village was occupied "after some light resistance."<ref name=Khalidi211/> |

The Israeli Air Force bombed the area of Bayt Nattif on October 19, 1948, which started panic flights from Bayt Nattif and [[Bayt Jibrin]].<ref>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA468 468], note #32 in Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA494 494]</ref> Bayt Nattif was depopulated during the [[1948 Arab-Israeli War]] on October 21, 1948 under ''[[Operation Ha-Har]]'', by the Fourth Battalion of the [[Har'el Brigade]].<ref name=Khalidi211/><ref name=Morris2008p329>Morris, 2008, p. 329</ref><ref>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA462 462]</ref> There are conflicting reports about its conquest, one [[Palmah]] report says that the villagers "fled for their lives",<ref name=Morris466>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA466 466] note #14, in Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA493 493]. "Book of the Palmah, II" pp. 646, 652</ref> while a Haganah report says that the village was occupied "after some light resistance."<ref name=Khalidi211/> |

||

During late 1948, the [[Israel Defense Forces|IDF]] continued to destroy |

During late 1948, the [[Israel Defense Forces|IDF]] continued to destroy abandoned Arab villages, in order to block the villagers return.<ref name=Morris400/> Benny Marshak, the 'Education Officer' of the [[Palmah]], frequently spoke in favour of the destruction of (usually hostile) clusters of abandoned villages, including those in the Jerusalem Corridor.<ref>Benny Morris, ''The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited'', Cambridge University Press 2004, [https://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA355&hl=en#v=onepage&q&f=false p. 356]; ''ibid''., footnote # 98 on [https://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA355&hl=en#v=onepage&q&f=false p.400].</ref> Among these destroyed villages was Bayt Nattif. There are also conflicting reports about which other villages were destroyed with it; one report says that [[Dayr Aban]] was destroyed with it,<ref name =Morris400>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA355 355], footnote #85, on Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA400 400]: Harel Brigade HQ, "Daily report for 22 October", 23 Oct. 1948, IDFA 4775\49\3, for the destruction of Bait Nattiv and [[Deir Aban]]</ref> while another report says that [[Dayr al-Hawa]] was destroyed with it.<ref name=Morris466/> |

||

On 5 November, Harel Brigade raided the area south of Bayt Nattif, driving out any Palestinian refugee they could find.<ref>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA518 518]</ref> |

On 5 November, Harel Brigade raided the area south of Bayt Nattif, driving out any Palestinian refugee they could find.<ref>Morris, 2004, p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=uM_kFX6edX8C&pg=PA518 518]</ref> |

||

| Line 103: | Line 106: | ||

*{{cite book|last1=Robinson|first1=Edward|authorlink1=Edward Robinson (scholar)|last2=Smith|first2=Eli|authorlink2=Eli Smith|year=1841|url=http://archive.org/details/biblicalresearch03robiuoft |title=Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838| location=Boston|publisher=[[Crocker & Brewster]]|volume=3}} |

*{{cite book|last1=Robinson|first1=Edward|authorlink1=Edward Robinson (scholar)|last2=Smith|first2=Eli|authorlink2=Eli Smith|year=1841|url=http://archive.org/details/biblicalresearch03robiuoft |title=Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838| location=Boston|publisher=[[Crocker & Brewster]]|volume=3}} |

||

*{{cite book|title=Palestine in Transformation, 1856-1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development|url=http://books.google.com/?id=cMVtAAAAMAAJ|first1=Alexander|last1=Schölch|year=1993|publisher=[[Institute for Palestine Studies]]|isbn=0-88728-234-2}} |

*{{cite book|title=Palestine in Transformation, 1856-1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development|url=http://books.google.com/?id=cMVtAAAAMAAJ|first1=Alexander|last1=Schölch|year=1993|publisher=[[Institute for Palestine Studies]]|isbn=0-88728-234-2}} |

||

*{{cite journal|last=Toledano |first=E. |title=The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population |url=http://alkindi.ideo-cairo.org/manifestation/61348|journal =Archivum Ottomanicum|volume=9|pages=279–319 |date=1984}} |

*{{cite journal|last=Toledano |first=E. |title=The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population |url=http://alkindi.ideo-cairo.org/manifestation/61348|journal =Archivum Ottomanicum|volume=9|pages=279–319 |date=1984}} |

||

*{{Cite book|last=Younger|first=K. Lawson Jr|chapter=Joshua|url=http://books.google.com.au/books?id=2Vo-11umIZQC&pg=PA174&lpg=PA174&dq=Joshua+K+Lawson+Younger#v=onepage&q=Joshua%20K%20Lawson%20Younger&f=false |

|||

|editor=James D. G. Dunn and John William Rogerson|title=Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible|publisher=Eerdmans|year=2003|isbn=9780802837110}} |

|||

*{{cite journal | last1 = Zissu |first1=Boaz | last2 = Klein|first2=Eitan| title = A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills|url= http://lisa.biu.ac.il/files/lisa/shared/Zissu-Klein-IEJ_61-2011.pdf | journal = [[Israel Exploration Journal]] | volume = 61 (2) | year = 2011 | pages = 196–216}} |

*{{cite journal | last1 = Zissu |first1=Boaz | last2 = Klein|first2=Eitan| title = A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills|url= http://lisa.biu.ac.il/files/lisa/shared/Zissu-Klein-IEJ_61-2011.pdf | journal = [[Israel Exploration Journal]] | volume = 61 (2) | year = 2011 | pages = 196–216}} |

||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

Revision as of 02:02, 7 October 2015

Template:Infobox former Arab villages in Palestine

Bayt Nattif (

In 1945 it had a population of 2,150. Bayt Nattif contained several shrines, including a notable one dedicated to al-Shaykh Ibrahim. In a Judeo-historic context, the land whereon lies Bayt Nattif and the adjacent cities of History

Early history

Bayt Nattif was known under the Romans as Bayt Letepha.[2] According to Josephus, the city was sacked under Vespasian and Titus, during the first Jewish uprising against Rome.[5]

The city had been assigned the status of toparchy, one of eleven toparchies or prefectures in Judaea given certain administrative responsibilities.[6]

During the 12th year of the reign of Nero, when the Roman army had suffered a great defeat under Cestius, with more than five-thousand foot soldiers killed, the people of the surrounding countryside feared reprisals from the Roman army and made haste to appoint generals and to fortify their cities. Generals were at that time appointed for Idumea, namely, over the entire region immediately south and south-west of Jerusalem, and which incorporated within it the towns of Bethletephon, Betaris, Kefar Tobah,

Based upon archaeological finds that were discovered in Bayt Nattif, the city was still an important site in the Late Roman period. The place was now inhabited by Roman citizens and veterans, who settled the region as part of the Romanisation process that took place in the rural areas of Judaea after the Bar Kokhba war.[8]

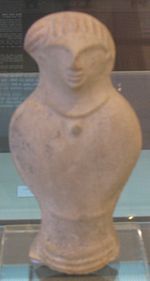

The Bayt Nattif lamp[9] is named for a type of ceramic oil lamp found during the archaeological excavation of two cisterns at Bayt Nattif in southern Judaea.[10] Bayt Nattif was located 20 kilometers southwest of Jerusalem, midway between Beit Guvrin and Jerusalem. Based on the discovery of unused oil lamps and molds, it is believed that in ancient times the village manufactured late Roman or Byzantine pottery, possibly selling its wares in Jerusalem and Beit Guvrin.[11]

Ottoman period (1517 – 1917)

In 1596, Bayt Nattif was listed among villages belonging to the

In 1838

In 1863

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Bayt Nattif as being "a village of fair size, standing high on a flat-topped ridge between two broad valleys. On the south, about 400 feet below, is a spring (`Ain el Kezbeh), and on the north a rock-cut tomb was found. There are fine olive-groves round the place, and the open valleys are very fertile in corn."[23]

British Mandate (1917 – 1948)

For all practical purposes, the British inherited from their Turkish counterparts the existing laws in regard to land tenures as defined in the

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Bayt Nattif had a population of 1,112, all Muslims,[27] increasing in the 1931 census to 1,649, still all Muslim, in a total of 329 houses (which figure includes houses built in the nearby ruin, Khirbet Umm al-Ra’us).[28]

In 1934, Dimitri Baramki of the Mandate Department of Antiquities directed the excavation of two cisterns in the village of Bayt Nattif which produced mostly ceramic ware dating from between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE.[2]

By 1945, the population had increased to 2,150.

1948 war, and depopulation

In the proposed 1947

The official Jewish account (The "History of

The Israeli Air Force bombed the area of Bayt Nattif on October 19, 1948, which started panic flights from Bayt Nattif and

During late 1948, the

On 5 November, Harel Brigade raided the area south of Bayt Nattif, driving out any Palestinian refugee they could find.[41]

Israeli rule (1948 – ff.)

Netiv HaLamed-Heh was built on village land in 1949, while Aviezer and Neve Michael were built on village land in 1958.[33]

Today, the land whereon was once built Bayt Nattif comprises what is now called Halamed He Forest (Template:Lang-he-n) and is maintained by the Jewish National Fund.

Gallery

-

Razed structure at Bayt Nattif

-

Mouth of cistern near Bayt Nattif

-

General view of Bayt Nattif, looking south toward theElah Valley

-

Carob tree on the ascent to Bayt Nattif

References

- ^ In an interview with Muhammad Abu Halawa (born 1929), he disclosed unto his interviewer, Rakan Mahmoud, in 2009, that the original name of the village was Bayt Lettif, but since it was phonetically easier for the tongue to say Bayt Nattif, so did the name change. See Palestine Oral History: Interview with Muhammad Halawa #1, Bayt Nattif-Hebron, Arabic (In video: 2:48 – 2:56)

- ^ a b c d e f g Khalidi, 1992, p. 211 Cite error: The named reference "Khalidi211" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Joshua: Book of; Joshua 15: 33–36; year of conquest based on Seder Olam Rabbah (ed. M.D. Yerushalmi), chapter 11, Jerusalem 1971, pp. 39–40

- ^ Younger, p. 183

- ^ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) iv.viii.1.

- Joppa. These all answered to Jerusalem.Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), iii.iii.4

- ^ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), ii.xx.3-4

- ^ Zissu and Klein, 2011, A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills

- ^ Judean Beit Nattif Oil Lamp

- ^ New light on daily life at Beth Shean

- ^ Jerusalem Ceramic Chronology: Circa 200-800 CE, Jodi Magness

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 114

- ^ Toledano, 1984, p. 290, gives the position of 34°59′20″E 31°41′45″N

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 341-347

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 16

- ^ Schölch, 1993, p. 229

- ^ Benvenisti, 2002, in a chapter named "The Convenience of the Crusades", p. 301

- ^ Schölch, 1993, p. 231

- ^ Schölch, 1993, p. 232

- ^ Finn, 1878, vol 2, pp. 194-210

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pt. 2, pp. 374-377

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pt. 3, pp. 329-330

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 24

- ^ A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), chapter 8, section 5, British Mandate Government of Palestine: Jerusalem 1946, p. 255

- ^ A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), chapter 8, section 4, British Mandate Government of Palestine: Jerusalem 1946, p. 246

- ^ A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), chapter 8, section 4, British Mandate Government of Palestine: Jerusalem 1946, pp. 246 – 247

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Hebron, p. 10

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 28

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 50

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 93

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 143

- ^ "Map of UN Partition Plan". United Nations. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Khalidi212was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Morris, 2004, p. 74

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 468, note #32 in Morris, 2004, p. 494

- ^ Morris, 2008, p. 329

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 462

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. 466 note #14, in Morris, 2004, p. 493. "Book of the Palmah, II" pp. 646, 652

- ^ Deir Aban

- ^ Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press 2004, p. 356; ibid., footnote # 98 on p.400.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 518

Bibliography

- Baramki, D.C. (1934). "Recent Discoveries of Byzantine Remains in Palestine. A Mosaic Pavement at Beit Nattif". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 4: 119–121.

- Baramki, D.C. (1936). "Two Roman Cisterns at Beit Nattif". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 5: 3–10.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922 (PDF). Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 978-0-520-23422-2.

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, Herbert H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p. 52)

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4. (p. 918)

- Finn, James (1878). Elizabeth A. Finn (ed.). Stirring Times, or, Records from Jerusalem Consular Chronicles of 1853 to 1856. Edited and Compiled by His Widow E. A. Finn. With a Preface by the Viscountess Strangford. Vol. 2. London: C.K. Paul & co.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, Sami (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas (PDF). Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ISBN 1-902210-67-0.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schölch, Alexander (1993). Palestine in Transformation, 1856-1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development. ISBN 0-88728-234-2.

- Toledano, E. (1984). "The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population". Archivum Ottomanicum. 9: 279–319.

- Younger, K. Lawson Jr (2003). "Joshua". In James D. G. Dunn and John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Zissu, Boaz; Klein, Eitan (2011). "A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 61 (2): 196–216.

External links

- Welcome To Bayt Nattif

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Bayt Nattif, Palestine Family.net