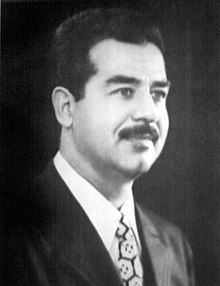

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein | |

|---|---|

صدام حسين | |

Mohammad Bahr al-Ulloum (as Acting President of the Governing Council of Iraq) | |

| In office 16 July 1979 – 23 March 1991 | |

| President | Himself |

| Preceded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Succeeded by | Sa'dun Hammadi |

| Secretary General of the National Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party | |

| In office January 1992 – 30 December 2006 | |

| Preceded by | Michel Aflaq |

| Succeeded by | Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri |

| Regional Secretary of the Regional Command of the Iraqi Regional Branch | |

| In office 16 July 1979 – 30 December 2006 | |

| National Secretary |

|

| Preceded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Succeeded by | Izzat Ibrahim ad-Douri |

| In office February 1964 – October 1966 | |

| Preceded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Vice President of Iraq | |

| In office 17 July 1968 – 16 July 1979 | |

| President | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Preceded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Succeeded by | Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri |

| Member of the Regional Command of the Iraqi Regional Branch | |

| In office February 1964 – 9 April 2003 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 April 1937[a] Al-Awja, Saladin Governorate, Kingdom of Iraq |

| Died | 30 December 2006 (aged 69) Camp Justice, Kadhimiya, Baghdad, Iraq |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | Al-Awja |

| Political party |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Iraqi Armed Forces |

| Rank | Marshal |

| Battles/wars | |

Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti.

Saddam was born in the village of

Upon taking office, Saddam instituted the

In 2003, the United States and

Saddam has been accused of running a repressive

Early life and education

Saddam Hussein was born in

Later in his life, relatives from his native city became some of his closest advisors and supporters. Under the guidance of his uncle, he attended a nationalistic high school in Baghdad. After secondary school, Saddam studied at an

Revolutionary sentiment was characteristic of the era in Iraq and throughout the Middle East. In Iraq,

In 1958, a year after Saddam had joined the Ba'ath party, army officers led by General

Rise to power

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

|

The Ba'ath Party was originally represented in Qasim's cabinet; however, Qasim—reluctant to join Nasser's newly formed

At the time of the attack, the Ba'ath Party had fewer than 1,000 members,[30] however the failed assassination attempt led to widespread exposure for Saddam and the Ba'ath within Iraq, where both had previously languished in obscurity, and later became a crucial part of Saddam's public image during his tenure as president of Iraq.[28][31] Kanan Makiya recounts:

The man and the myth merge in this episode. His biography—and Iraqi television, which stages the story ad nauseam—tells of his familiarity with guns from the age of ten; his fearlessness and loyalty to the party during the 1959 operation; his bravery in saving his comrades by commandeering a car at gunpoint; the bullet that was gouged out of his flesh under his direction in hiding; the iron discipline that led him to draw a gun on weaker comrades who would have dropped off a seriously wounded member of the hit team at a hospital; the calculating shrewdness that helped him save himself minutes before the police broke in leaving his wounded comrades behind; and finally the long trek of a wounded man from house to house, city to town, across the desert to refuge in Syria.[32]

Army officers with ties to the Ba'ath Party overthrew Qasim in the Ramadan Revolution coup of February 1963; long suspected to be supported by the CIA,[39][40] however pertinent contemporary documents relating to the CIA's operations in Iraq have remained classified by the U.S. government,[41][42] although the Ba'athists are documented to have maintained supportive relationships with U.S. officials before, during, and after the coup.[43][44] Ba'athist leaders were appointed to the cabinet and Abdul Salam Arif became president. Arif dismissed and arrested the Ba'athist leaders later that year in the November 1963 Iraqi coup d'état. Being exiled in Egypt at the time, Saddam played no role in the 1963 coup or the brutal anti-communist purge that followed; although he returned to Iraq after the coup, becoming a key organizer within the Ba'ath Party's civilian wing upon his return.[45] Unlike during the Qasim years, Saddam remained in Iraq following Arif's anti-Ba'athist purge in November 1963, and became involved in planning to assassinate Arif. In marked contrast to Qasim, Saddam knew that he faced no death penalty from Arif's government and knowingly accepted the risk of being arrested rather than fleeing to Syria again. Saddam was arrested in October 1964 and served approximately two years in prison before escaping in 1966.[46] In 1966, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr appointed him Deputy Secretary of the Regional Command. Saddam, who would prove to be a skilled organizer, revitalized the party.[47] He was elected to the Regional Command, as the story goes, with help from Michel Aflaq—the founder of Ba'athist thought.[48] In September 1966, Saddam initiated an extraordinary challenge to Syrian domination of the Ba'ath Party in response to the Marxist takeover of the Syrian Ba'ath earlier that year, resulting in the Party's formalized split into two separate factions.[49] Saddam then created a Ba'athist security service, which he alone controlled.[50]

1979 Ba'ath Party Purge

Saddam convened an assembly of Ba'ath party leaders on 22 July 1979. During the assembly, which he ordered videotaped,[51] Saddam claimed to have found a fifth column within the Ba'ath Party and directed Muhyi Abdel-Hussein to read out a confession and the names of 68 alleged co-conspirators. These members were labelled "disloyal" and were removed from the room one by one and taken into custody. After the list was read, Saddam congratulated those still seated in the room for their past and future loyalty. The 68 people arrested at the meeting were subsequently tried together and found guilty of treason; 22 were sentenced to execution. Other high-ranking members of the party formed the firing squad. By 1 August 1979, hundreds of high-ranking Ba'ath party members had been executed.[52][53]

Paramilitary and police organizations

"There is a feeling that at least three million Iraqis are watching the eleven million others."

—"A European diplomat", quoted in The New York Times, April 3, 1984.[54]

Iraqi society fissures along lines of language, religion and ethnicity. The Ba'ath Party, secular by nature, adopted Pan-Arab ideologies which in turn were problematic for significant parts of the population. Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Iraq faced the prospect of régime change from two Shi'ite factions (Dawa and SCIRI) which aspired to model Iraq on its neighbour Iran as a Shia theocracy. A separate threat to Iraq came from parts of the ethnic Kurdish population of northern Iraq which opposed being part of an Iraqi state and favored independence (an ongoing ideology which had preceded Ba'ath Party rule). To alleviate the threat of revolution, Saddam afforded certain benefits to the potentially hostile population. Membership in the Ba'ath Party remained open to all Iraqi citizens regardless of background, and repressive measures were taken against its opponents.[55]

The major instruments for accomplishing this control were the paramilitary and police organizations. Beginning in 1974, Taha Yassin Ramadan (himself a Kurdish Ba'athist), a close associate of Saddam, commanded the People's Army, which had responsibility for internal security. As the Ba'ath Party's paramilitary, the People's Army acted as a counterweight against any coup attempts by the regular armed forces. In addition to the People's Army, the Department of General Intelligence was the most notorious arm of the state-security system, feared for its use of torture and assassination. Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti, Saddam's younger half-brother, commanded Mukhabarat. Foreign observers believed that from 1982 this department operated both at home and abroad in its mission to seek out and eliminate Saddam's perceived opponents.[55][56]

Saddam was notable for using terror against his own people. The Economist described Saddam as "one of the last of the 20th century's great dictators, but not the least in terms of egotism, or cruelty, or morbid will to power."[57] Saddam's regime brought about the deaths of at least 250,000 Iraqis[58] and committed war crimes in Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International issued regular reports of widespread imprisonment and torture. Conversely, Saddam used Iraq's oil wealth to develop an extensive patronage system for the regime's supporters.[59]

Although Saddam is often described as a totalitarian leader, Joseph Sassoon notes that there are important differences between Saddam's repression and the totalitarianism practiced by Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, particularly with regard to freedom of movement and freedom of religion.[59]

Vice Presidency (1968–1979)

In July 1968, Saddam participated in a

Succession

In 1976, Saddam rose to the position of general in the Iraqi armed forces, and rapidly became the

In 1979, al-Bakr started to make treaties with Syria, also under Ba'athist leadership, that would lead to unification between the two countries. Syrian President

Political program

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as vice chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council, formally al-Bakr's second-in-command, Saddam built a reputation as a progressive, effective politician.[63] At this time, Saddam moved up the ranks in the new government by aiding attempts to strengthen and unify the Ba'ath party and taking a leading role in addressing the country's major domestic problems and expanding the party's following.

After the Ba'athists took power in 1968, Saddam focused on attaining stability in a nation riddled with profound tensions. Long before Saddam, Iraq had been split along social, ethnic, religious, and economic fault lines: Sunni versus Shi'ite, Arab versus Kurd, tribal chief versus urban merchant, nomad versus peasant.[64] The desire for stable rule in a country rife with factionalism led Saddam to pursue both massive repression and the improvement of living standards.[64]

Saddam actively fostered the modernization of the Iraqi economy along with the creation of a strong security apparatus to prevent coups within the power structure and insurrections apart from it. Ever concerned with broadening his base of support among the diverse elements of Iraqi society and mobilizing mass support, he closely followed the administration of state welfare and development programs.[citation needed]

At the center of this strategy was Iraq's oil. On 1 June 1972, Saddam oversaw the seizure of international oil interests, which, at the time, dominated the country's oil sector. A year later, world oil prices rose dramatically as a result of the

Within just a few years, Iraq was providing social services that were unprecedented among Middle Eastern countries. Saddam established and controlled the "National Campaign for the Eradication of Illiteracy" and the campaign for "Compulsory Free Education in Iraq", and largely under his auspices, the government established universal free schooling up to the highest education levels; hundreds of thousands learned to read in the years following the initiation of the program. The government also supported families of soldiers, granted free hospitalization to everyone, and gave subsidies to farmers. Iraq created one of the most modernized public-health systems in the Middle East, earning Saddam an award from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[65][66]

With the help of increasing oil revenues, Saddam diversified the largely oil-based Iraqi economy. Saddam implemented a national infrastructure campaign that made great progress in building roads, promoting mining, and developing other industries. The campaign helped Iraq's energy industries. Electricity was brought to nearly every city in Iraq, and many outlying areas. Before the 1970s, most of Iraq's people lived in the countryside and roughly two-thirds were peasants. This number would decrease quickly during the 1970s as global oil prices helped revenues to rise from less than a half billion dollars to tens of billions of dollars and the country invested into industrial expansion. He nationalised independent banks, eventually leaving the banking system insolvent due to inflation and bad loans.[67]

The oil revenue benefited Saddam politically.[57] According to The Economist, "Much as Adolf Hitler won early praise for galvanizing German industry, ending mass unemployment and building autobahns, Saddam earned admiration abroad for his deeds. He had a good instinct for what the "Arab street" demanded, following the decline in Egyptian leadership brought about by the trauma of Israel's six-day victory in the 1967 war, the death of the pan-Arabist hero, Gamal Abdul Nasser, in 1970, and the "traitorous" drive by his successor, Anwar Sadat, to sue for peace with the Jewish state. Saddam's self-aggrandizing propaganda, with himself posing as the defender of Arabism against Zionist or Persian intruders, was heavy-handed, but consistent as a drumbeat. It helped, of course, that his mukhabarat (secret police) put dozens of Arab news editors, writers and artists on the payroll."[57]

In 1972, Saddam signed a 15-year Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. According to historian Charles R. H. Tripp, the treaty upset "the US-sponsored security system established as part of the Cold War in the Middle East. It appeared that any enemy of the Baghdad regime was a potential ally of the United States."[68] In response, the US covertly financed Kurdish rebels led by Mustafa Barzani during the Second Iraqi–Kurdish War; the Kurds were defeated in 1975, leading to the forcible relocation of hundreds of thousands of Kurdish civilians.[68]

Saddam focused on fostering loyalty to the Ba'athists in the rural areas. After nationalizing foreign oil interests, Saddam supervised the modernization of the countryside, mechanizing agriculture on a large scale, and distributing land to peasant farmers.[69] The Ba'athists established farm cooperatives and the government also doubled expenditures for agricultural development in 1974–1975. Saddam's welfare programs were part of a combination of "carrot and stick" tactics to enhance support for Saddam. The state-owned banks were put under his thumb. Lending was based on cronyism.[67]

Peace treaty with Iran

A peace treaty, which aimed to address the Shatt al-Arab dispute, was signed in 1975.

The Algiers Agreement was based on the principles of territorial integrity, respect for sovereignty, non-interference in internal affairs, and the peaceful resolution of disputes.[70] The agreement established a new border line along the Shatt al-Arab, dividing the waterway equally between Iran and Iraq up to the midpoint.[70] Iran made significant concessions in the agreement, including relinquishing its claims on the eastern bank of the Shatt al-Arab, which had been under Iranian control.[70] Saddam Hussein aimed to secure Iraq's territorial claims, particularly regarding the Shatt al-Arab waterway, which had been a longstanding source of contention between Iran and Iraq.[70]

Both parties recognized each other's sovereignty and territorial integrity, affirming the principle of non-aggression.[70] The Algiers Agreement called for the restoration of full diplomatic relations between Iran and Iraq, including the exchange of ambassadors.[70] The agreement emphasized the importance of economic cooperation between the two countries, particularly in areas such as trade, transport, and joint development projects.[70] The signing of the Algiers Agreement occurred during a period of relative stability in Iraq, with Saddam Hussein gradually consolidating power within the ruling Ba'ath Party.[70] As Vice President, Saddam Hussein played a pivotal role in the negotiations leading up to the Algiers Agreement, representing Iraq's interests.[70] Saddam Hussein's growing influence within the Iraqi government allowed him to shape Iraq's approach and stance during the negotiation process.[70] Following the agreement, Iraq and Iran restored full diplomatic relations and exchanged ambassadors, representing a significant diplomatic breakthrough.[70] The Algiers Agreement emphasized the importance of economic cooperation between Iraq and Iran, particularly in areas like trade and joint development projects.[70] This agreement, while ultimately unable to prevent future hostilities, remained a notable diplomatic achievement for Iraq during Saddam Hussein's early political career.[70]

Presidency (1979–2003)

Domestic policy

Kurdish autonomy

Although it has been debated his position on Kurdish Politics, Saddam Hussein has allowed autonomy for the Kurds to an extent,[71] with Kurds being allowed to speak Kurdish in schools, on television, and even in newspapers, with textbooks being translated for the Kurdish regions. With Kurds in Iraq being able to elect a Kurdish representative to go to Baghdad.[72] Saddam Hussein had already signed a deal in 1970 to grant the Kurds autonomy, but Mustafa Barazani eventually disagreed with the deal, which incited the Second Iraqi–Kurdish War.

Education and literacy reforms

Under Saddam Hussein's regime, substantial reforms in education and literacy took place, with Saddam Hussein introducing mandatory reading groups for adults, with punishments for not attending consisting of heavy fines, and even jail time. UNESCO awarded Iraq for having "Most effective literacy campaign in the world.",[73] with estimates being that in 1979 alone, over 2 million Iraqi adults were studying in more than 28,735 literacy schools, with over 75,000 teachers.[74] Saddam Hussein's regime also mandated education for primary to high school, with Saddam's regime also mandating free tuition for university students.

Economic reforms

Nationalization of oil was implemented, which aimed to achieve economic independence.[75] By the late 1970s, Iraq experienced significant economic growth, with a budget reserve surpassing US$35 billion. The value of 1 Iraqi dinar was worth more than 3 dollars, making it one of the most notable economic expansions in the region. Saddam Hussein's regime aimed to diversify the Iraqi economy beyond oil. The government invested in various industries, including petrochemicals, fertilizer production, and textile manufacturing, to reduce dependence on oil revenues and promote economic self-sufficiency.[76] By the 1970s, women employment rate also increased.

Following invasion of Kuwait and initiating the Gulf War, Iraq was

Social reforms

Saddam Hussein also took steps to promote women's rights within Iraq. By the late 1970s, women in Iraq held significant roles in society, representing 46% of all teachers, 29% of all doctors, 46% of all dentist and 70% of all pharmacists. These advancements signaled progress in women's participation in various professional fields.[citation needed] Women also saw drastic increase in rights in other-aspects of life, with women being given equal-rights in marriage, divorce, inheritance, and custody.[79] Women in Iraq also had the ability to pass their citizenship down to their children even if they married a non-Iraqi, which Iraqi women no longer have the ability to do. Women's education no longer was a luxury, with women having the same opportunities as men in higher education.[79]

Saddam Hussein also introduced social security programs, with the notable parts of the program consisting of disability benefits, with disabled people in Iraq becoming eligible for financial assistance.[80] It also introduced healthcare coverage, ensuring Iraqi citizens had access to healthcare and medication when needed,[81] Although during the 90's Iraqi-healthcare decreased in its effectiveness with the sanctions restricting basic-medical equiptment and supplies from getting into Iraq.[82]

Freedom of religion

Iraq under Saddam Hussein was known for religious tolerance, as different religious minorities coexisted peacefully. During his tenure, more than 1.2 million Christians lived in Iraq, highlighting the country's diverse religious landscape. Tariq Aziz, who was a Chaldean, held various political positions in the Ba'athist government and was a close advisor to Saddam Hussein. Due to close relations with Chaldeans, Saddam donated heavy amount to Chaldean churches and institutions across the United States, despite having hostile relations.[citation needed]

During Saddam Hussein's rule, the

Saddam Hussein was recognized for safeguarding the Mandaean minority in Iraq.[87] with Mandaeans being given state protection under Saddam Hussein, Saddams personnal Jeweller was a Mandaean. However, after his regime's downfall, Mandaeans faced severe persecution, and constant kidnappings, and often expressed that they were better under Saddam's rule.[88]

Foreign policy

Foreign affairs

Saddam developed a reputation for liking expensive goods, such as his diamond-coated Rolex wristwatch, and sent copies of them to his friends around the world. To his ally Kenneth Kaunda Saddam once sent a Boeing 747 full of presents—rugs, televisions, ornaments.[citation needed] Saddam enjoyed a close relationship with Russian intelligence agent Yevgeny Primakov that dated back to the 1960s; Primakov may have helped Saddam to stay in power in 1991.[89]

Saddam visited only two Western countries. The first visit took place in December 1974, when the Caudillo of Spain, Francisco Franco, invited him to Madrid and he visited Granada, Córdoba and Toledo.[90] In September 1975 he met with Prime Minister Jacques Chirac in Paris, France.[91]

Several Iraqi leaders, Lebanese arms merchant Sarkis Soghanalian and others have claimed that Saddam financed Chirac's party. In 1991 Saddam threatened to expose those who had taken largesse from him: "From Mr. Chirac to Mr. Chevènement, politicians and economic leaders were in open competition to spend time with us and flatter us. We have now grasped the reality of the situation. If the trickery continues, we will be forced to unmask them, all of them, before the French public."[91] France armed Saddam and it was Iraq's largest trade partner throughout Saddam's —rule. Seized documents show how French officials and businessmen close to Chirac, including Charles Pasqua, his former interior minister, personally benefitted from the deals with Saddam.[91]

Because Saddam Hussein rarely left Iraq, Tariq Aziz, one of Saddam's aides, traveled abroad extensively and represented Iraq at many diplomatic meetings.[92] In foreign affairs, Saddam sought to have Iraq play a leading role in the Middle East. Iraq signed an aid pact with the Soviet Union in 1972, and arms were sent along with several thousand advisers. The 1978 crackdown on Iraqi Communists and a shift of trade toward the West strained Iraqi relations with the Soviet Union; Iraq then took on a more Western orientation until the Gulf War in 1991.[93]

After the

Palestine is Arab and must be liberated from the river to the sea and all the Zionists who emigrated to the land of Palestine must leave.

— Saddam Hussein

Nearly from its founding as a modern state in 1920, Iraq has had to deal with Kurdish separatists in the northern part of the country.[96] Saddam did negotiate an agreement in 1970 with separatist Kurdish leaders, giving them autonomy, but the agreement broke down. The result was brutal fighting between the government and Kurdish groups and Iraqi bombing of Kurdish villages in Iran, which caused Iraqi relations with Iran to deteriorate. After Saddam negotiated the 1975 treaty with Iran, the Shah withdrew support for the Kurds, who were defeated.

Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988)

In early 1979, Iran's Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Pahlavi dynasty were overthrown by the Islamic Revolution, thus giving way to an Islamic republic led by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.[98] The influence of revolutionary Shi'ite Islam grew apace in the region, particularly in countries with large Shi'ite populations, especially Iraq.[98] Saddam feared that radical Islamic ideas—hostile to his secular rule—were rapidly spreading inside his country among the majority Shi'ite population.[98] Despite Saddam's fears of massive unrest, Iran's attempts to export its Islamic Revolution were largely unsuccessful in rallying support from Shi'ites in Iraq and the Gulf states. Most Iraqi Shi'ites, who comprised the majority of the Iraqi Armed Forces, chose their own country over their Shi'ite Iranian coreligionists during the Iran–Iraq War that ensued.[99]

There had also been bitter enmity between Saddam and Khomeini since the 1970s.[98] Khomeini, having been exiled from Iran in 1964, took up residence in Iraq, at the Shi'ite holy city of Najaf.[98] There he involved himself with Iraqi Shi'ites and developed a strong religious and political following against the Iranian Government, which Saddam tolerated.[98] When Khomeini began to urge the Shi'ites there to overthrow Saddam and under pressure from the Shah, who had agreed to a rapprochement between Iraq and Iran in 1975, Saddam agreed to expel Khomeini in 1978 to France.[98] Here, Khomeini gained media connections and collaborated with a much larger Iranian community, to his advantage.[98]

After Khomeini gained power, skirmishes between Iraq and revolutionary Iran occurred for ten months over the sovereignty of the disputed Shatt al-Arab waterway, which divides the two countries.[98] During this period, Saddam Hussein publicly maintained that it was in Iraq's interest not to engage with Iran, and that it was in the interests of both nations to maintain peaceful relations.[98] In a private meeting with Salah Omar al-Ali, Iraq's permanent ambassador to the United Nations, he revealed that he intended to invade and occupy a large part of Iran within months.[98]

In the first days of the war, there was heavy ground fighting around strategic ports as Iraq launched an attack on Khuzestan. After making some initial gains, Iraq's troops began to suffer losses from human wave attacks by Iran. By 1982, Iraq was on the defensive and looking for ways to end the war.[98]

At this point, Saddam asked his ministers for candid advice.[98] Health Minister Dr. Riyadh Ibrahim suggested that Saddam temporarily step down to promote peace negotiations.[98] Initially, Saddam Hussein appeared to take in this opinion as part of his cabinet democracy. A few weeks later, Dr. Ibrahim was sacked when held responsible for a fatal incident in an Iraqi hospital where a patient died from intravenous administration of the wrong concentration of potassium supplement. Dr. Ibrahim was arrested a few days after his removal from the cabinet. He was known to have publicly declared before that arrest that he was "glad that he got away alive." Pieces of Ibrahim's dismembered body were delivered to his wife the next day.[101]

Iraq quickly found itself bogged down in one of the longest and most destructive wars of attrition of the 20th century.[98] During the war, Iraq used chemical weapons against Iranian forces fighting on the southern front and Kurdish separatists who were attempting to open up a northern front in Iraq with the help of Iran.[98] Iraqi Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz later acknowledged Iraq's use of chemical weapons against Iran, but said that Iran had used them against Iraq first.[102] These chemical weapons were developed by Iraq from materials and technology supplied primarily by West German companies as well as using dual-use technology imported following the Reagan administration's lifting of export restrictions.[103] The US government also supplied Iraq with "satellite photos showing Iranian deployments.",[104] which were later deemed to be misleading intelligence information designed to prolong the war with Iran and increase US influence in the region, contributing to the Iraqi defeat in the First Battle of al-Faw in February 1986.[105] In a US bid to open full diplomatic relations with Iraq, the country was removed from the US list of State Sponsors of Terrorism in February 1982.[106] Ostensibly, this was because of improvement in the regime's record, although former US Assistant Secretary of Defense Noel Koch later stated, "No one had any doubts about [the Iraqis'] continued involvement in terrorism ... The real reason was to help them succeed in the war against Iran."[107] The Soviet Union, France, and China together accounted for over 90% of the value of Iraq's arms imports between 1980 and 1988.[108] While the United States supplied Iraq with arms, dual-use technology and economic aid, it was also involved in a covert and illegal arms deal, providing sanctioned Iran with weaponry. This political scandal became known as the Iran–Contra affair.[109]

Saddam reached out to other Arab governments for cash and political support during the war, particularly after Iraq's oil industry severely suffered at the hands of the

The bloody eight-year war ended in a stalemate. Encyclopædia Britannica states: "Estimates of total casualties range from 1,000,000 to twice that number. The number killed on both sides was perhaps 500,000, with Iran suffering the greatest losses."[110] Neither side had achieved what they had originally desired and the borders were left nearly unchanged.[98] The southern, oil rich and prosperous Khuzestan and Basra area (the main focus of the war, and the primary source of their economies) were almost completely destroyed and were left at the pre-1979 border, while Iran managed to make some small gains on its borders in the Northern Kurdish area. Both economies, previously healthy and expanding, were left in ruins.[98]

Saddam borrowed tens of billions of dollars from other Arab states and a few billions from elsewhere during the 1980s to fight Iran, mainly to prevent the expansion of Shi'a radicalism.[98] This backfired on Iraq and the Arab states, for Khomeini was widely perceived as a hero for managing to defend Iran and maintain the war with little foreign support against the heavily backed Iraq and only managed to boost Islamic radicalism not only within the Arab states, but within Iraq itself, creating new tensions between the Sunni Ba'ath Party and the majority Shi'a population.[98] Faced with rebuilding Iraq's infrastructure and internal resistance, Saddam desperately re-sought cash, this time for postwar reconstruction.[98]

Anfal campaign

The

On 16 March 1988, the Kurdish town of Halabja was attacked with a mix of mustard gas and nerve agents during the Halabja massacre, killing between 3,200 and 5,000 people, and injuring 7,000 to 10,000 more, mostly civilians.[115][116][117] The attack occurred in conjunction with the Anfal campaign designed to reassert central control of the mostly Kurdish population of areas of northern Iraq and defeat the Kurdish peshmerga rebel forces. Following the incident, The U.S. State Department took the official position that Iran was partly to blame for the Halabja massacre.[118] A study by the Defense Intelligence Agency held Iran responsible for the attack. This assessment was subsequently used by the Central Intelligence Agency for much of the early 1990s.[119] Despite this, few observers today doubt that it was Iraq that executed the Halabja massacre.[120]

Tensions with Kuwait

The end of the war with Iran served to deepen latent tensions between Iraq and its wealthy neighbor Kuwait. Saddam urged the Kuwaitis to waive the Iraqi debt accumulated in the war, some $30 billion, but they refused.[122] Saddam pushed oil-exporting countries to raise oil prices by cutting back production; Kuwait refused, then led the opposition in OPEC to the cuts that Saddam had requested. Kuwait was pumping large amounts of oil, and thus keeping prices low, when Iraq needed to sell high-priced oil from its wells to pay off its huge debt.[122]

Saddam had consistently argued that Kuwait had historically been an integral part of Iraq, and had only come into being as a result of interference from the British government; echoing a belief that Iraqi nationalists had supported for the past fifty years. This belief was one of the few articles of faith uniting the political scene in a nation rife with sharp social, ethnic, religious, and ideological divides.[122] The extent of Kuwaiti oil reserves also intensified tensions in the region. The oil reserves of Kuwait (with a population of 2 million next to Iraq's 25) were roughly equal to those of Iraq. Taken together, Iraq and Kuwait sat on top of some 20 percent of the world's known oil reserves; Saudi Arabia held another 25 percent. Saddam still had an experienced and well-equipped army, which he used to influence regional affairs. He later ordered troops to the Iraq–Kuwait border.[122]

As Iraq–Kuwait relations rapidly deteriorated, Saddam was receiving conflicting information about how the US would respond to the prospects of an invasion. For one, Washington had been taking measures to cultivate a constructive relationship with Iraq for roughly a decade. The Reagan administration gave Iraq roughly $4 billion in agricultural credits to bolster it against Iran.[123] Saddam's Iraq became "the third-largest recipient of US assistance."[124]

Reacting to Western criticism in April 1990, Saddam threatened to destroy half of Israel with chemical weapons if it moved against Iraq.[125] In May 1990 he criticized US support for Israel warning that "the US cannot maintain such a policy while professing friendship towards the Arabs."[126] In July 1990 he threatened force against Kuwait and the UAE saying "The policies of some Arab rulers are American ... They are inspired by America to undermine Arab interests and security."[127] The US sent warplanes and combat ships to the Persian Gulf in response to these threats.[128]

The US ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, met with Saddam in an emergency meeting on 25 July 1990, where the Iraqi leader attacked American policy with regards to Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates (UAE):[129]

So what can it mean when America says it will now protect its friends? It can only mean prejudice against Iraq. This stance plus maneuvers and statements which have been made has encouraged the UAE and Kuwait to disregard Iraqi rights. If you use pressure, we will deploy pressure and force. We know that you can harm us although we do not threaten you. But we too can harm you. Everyone can cause harm according to their ability and their size. We cannot come all the way to you in the US, but individual Arabs may reach you. We do not place America among the enemies. We place it where we want our friends to be and we try to be friends. But repeated American statements last year made it apparent that America did not regard us as friends.

Glaspie replied:[129]

I know you need funds. We understand that and our opinion is that you should have the opportunity to rebuild your country. But we have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. ... Frankly, we can only see that you have deployed massive troops in the south. Normally that would not be any of our business. But when this happens in the context of what you said on your national day, then when we read the details in the two letters of the Foreign Minister, then when we see the Iraqi point of view that the measures taken by the UAE and Kuwait is, in the final analysis, parallel to military aggression against Iraq, then it would be reasonable for me to be concerned.

Saddam stated that he would attempt last-ditch negotiations with the Kuwaitis but Iraq "would not accept death."[129] US officials attempted to maintain a conciliatory line with Iraq, indicating that while George H. W. Bush and James Baker did not want force used, they would not take any position on the Iraq–Kuwait boundary dispute and did not want to become involved.[130] Later, Iraq and Kuwait met for a final negotiation session, which failed. Saddam then sent his troops into Kuwait. As tensions between Washington and Saddam began to escalate, the Soviet Union, under Mikhail Gorbachev, strengthened its military relationship with the Iraqi leader, providing him military advisers, arms and aid.[131]

Gulf War

On 2 August 1990, Saddam invaded Kuwait, initially claiming assistance to "Kuwaiti revolutionaries", thus sparking an international crisis. On 4 August an Iraqi-backed "Provisional Government of Free Kuwait" was proclaimed, but a total lack of legitimacy and support for it led to an 8 August announcement of a "merger" of the two countries. On 28 August Kuwait formally became the 19th Governorate of Iraq. Just two years after the 1988 Iraq and Iran truce, "Saddam Hussein did what his Gulf patrons had earlier paid him to prevent." Having removed the threat of Iranian fundamentalism he "overran Kuwait and confronted his Gulf neighbors in the name of Arab nationalism and Islam."[99]

When later asked why he invaded Kuwait, Saddam first claimed that it was because Kuwait was rightfully Iraq's 19th province and then said "When I get something into my head I act. That's just the way I am."[57] Saddam Hussein could pursue such military aggression with a "military machine paid for in large part by the tens of billions of dollars Kuwait and the Gulf states had poured into Iraq and the weapons and technology provided by the Soviet Union, Germany, and France."[99] It was revealed during his 2003–2004 interrogation that in addition to economic disputes, an insulting exchange between the Kuwaiti emir Al Sabah and the Iraqi foreign minister – during which Saddam claimed that the emir stated his intention to turn "every Iraqi woman into a $10 prostitute" by ruining Iraq financially – was a decisive factor in triggering the Iraqi invasion.[132] Shortly before he invaded Kuwait, he shipped 100 new Mercedes 200 Series cars to top editors in Egypt and Jordan. Two days before the first attacks, Saddam reportedly offered Egypt's Hosni Mubarak 50 million dollars in cash, "ostensibly for grain."[133]

US President George H. W. Bush responded cautiously for the first several days. On one hand, Kuwait, prior to this point, had been a virulent enemy of Israel and was the Persian Gulf monarchy that had the most friendly relations with the Soviets.

Cooperation between the US and the Soviet Union made possible the passage of resolutions in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) giving Iraq a deadline to leave Kuwait and approving the use of force if Saddam did not comply with the timetable. US officials feared Iraqi retaliation against oil-rich Saudi Arabia, since the 1940s a close ally of Washington, for the Saudis' opposition to the invasion of Kuwait. Accordingly, the US and a group of allies, including countries as diverse as Egypt, Syria and Czechoslovakia, deployed a massive number of troops along the Saudi border with Kuwait and Iraq in order to encircle the Iraqi army, the largest in the Middle East. Saddam's officers looted Kuwait, stripping even the marble from its palaces to move it to Saddam's own palace.[67]

During the period of negotiations and threats following the invasion, Saddam focused renewed attention on the Palestinian problem by promising to withdraw his forces from Kuwait if Israel would relinquish the occupied territories in the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Gaza Strip. Saddam's proposal further split the Arab world, pitting US- and Western-supported Arab states against the Palestinians. The allies ultimately rejected any linkage between the Kuwait crisis and Palestinian issues.

Saddam ignored the Security Council deadline. Backed by the Security Council, a US-led coalition launched round-the-clock missile and aerial attacks on Iraq, beginning 16 January 1991. Israel, though

In the end, the Iraqi army proved unable to compete on the battlefield with the highly mobile coalition land forces and their overpowering air support. Some 175,000 Iraqis were taken prisoner and casualties were estimated at over 85,000. As part of the cease-fire agreement, Iraq agreed to scrap all poison gas and germ weapons and allow UN observers to inspect the sites. UN trade sanctions would remain in effect until Iraq complied with all terms. Saddam publicly claimed victory at the end of the war.

1990s

Iraq's ethnic and religious divisions, together with the brutality of the conflict that this had engendered, laid the groundwork for postwar rebellions. In the aftermath of the fighting, social and ethnic unrest among Shi'ite Muslims, Kurds, and dissident military units threatened the stability of Saddam's government. Uprisings erupted in the Kurdish north and Shi'a southern and central parts of Iraq, but were ruthlessly repressed. Uprisings in 1991 led to the death of 100,000–180,000 people, mostly civilians.[139]

The US, which had urged Iraqis to rise up against Saddam, did nothing to assist the rebellions. The Iranians, despite the widespread Shi'ite rebellions, had no interest in provoking another war, while Turkey opposed any prospect of Kurdish independence, and the Saudis and other conservative Arab states feared an Iran-style Shi'ite revolution. Saddam, having survived the immediate crisis in the wake of defeat, was left firmly in control of Iraq, although the country never recovered either economically or militarily from the Gulf War.[99]

Saddam routinely cited his survival as "proof" that Iraq had in fact won the war against the US. This message earned Saddam a great deal of popularity in many sectors of the Arab world. John Esposito wrote, "Arabs and Muslims were pulled in two directions. That they rallied not so much to Saddam Hussein as to the bipolar nature of the confrontation (the West versus the Arab Muslim world) and the issues that Saddam proclaimed: Arab unity, self-sufficiency, and social justice." As a result, Saddam Hussein appealed to many people for the same reasons that attracted more and more followers to Islamic revivalism and also for the same reasons that fueled anti-Western feelings.[99]

One US Muslim observer[who?] noted: "People forgot about Saddam's record and concentrated on America ... Saddam Hussein might be wrong, but it is not America who should correct him." A shift was, therefore, clearly visible among many Islamic movements in the post war period "from an initial Islamic ideological rejection of Saddam Hussein, the secular persecutor of Islamic movements, and his invasion of Kuwait to a more populist Arab nationalist, anti-imperialist support for Saddam (or more precisely those issues he represented or championed) and the condemnation of foreign intervention and occupation."[99]

Some elements of

The United Nations-placed

Relations between the US and Iraq remained tense following the Gulf War. The US launched a

Saddam continued involvement in politics abroad. Video tapes retrieved after show his intelligence chiefs meeting with Arab journalists, including a meeting with the former managing director of Al-Jazeera, Mohammed Jassem al-Ali, in 2000. In the video Saddam's son Uday advised al-Ali about hires in Al-Jazeera: "During your last visit here along with your colleagues we talked about a number of issues, and it does appear that you indeed were listening to what I was saying since changes took place and new faces came on board such as that lad, Mansour." He was later sacked by Al-Jazeera.[148]

2000s

In 2002, Austrian prosecutors investigated Saddam government's transactions with

In 2002, a resolution sponsored by the

Political and cultural image

During his leadership, Saddam promoted the idea of dual nationalism which combines Iraqi nationalism and Arab nationalism, a much broader form of ethnic nationalism which supports Iraqi nationalism and links it to matters that impact Arabs as a whole.[152] Saddam Hussein believed that the recognition of the ancient Mesopotamian origins and heritage of Iraqi Arabs was complementary to supporting Arab nationalism.[152]

In the course of his reign, the Ba'athist regime officially included the historic Kurdish Muslim leader Saladin as a patriotic symbol in Iraq, while Saddam called himself son of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar and had stamped the bricks of ancient Babylon with his name and titles next to him.[153][154] During the Gulf War, Saddam claimed the historic roles of Nebuchadnezzar, Saladin and Gamal Abdel Nasser.[99]

He also conducted two

In the 15 October 2002 referendum he officially achieved 100% of approval votes and 100% turnout, as the electoral commission reported the next day that every one of the 11,445,638 eligible voters cast a "Yes" vote for the president.[157]

He erected statues around the country, which Iraqis toppled after his fall.[158][159]

2003 invasion and Iraq War

Many members of the international community, especially the US, continued to view Saddam as a bellicose tyrant who was a threat to the stability of the region. In his January 2002

After the passing of UNSC Resolution 1441, which demanded that Iraq give "immediate, unconditional and active cooperation" with UN and IAEA inspections,[162] Saddam allowed U.N. weapons inspectors led by Hans Blix to return to Iraq. During the renewed inspections beginning in November 2002, Blix found no stockpiles of WMD and noted the "proactive" but not always "immediate" Iraqi cooperation as called for by Resolution 1441.[163]

With war still looming on 24 February 2003, Saddam Hussein took part in an interview with CBS News reporter Dan Rather. Talking for more than three hours, he denied possessing any weapons of mass destruction, or any other weapons prohibited by UN guidelines. He also expressed a wish to have a live televised debate with George W. Bush, which was declined. It was his first interview with a US reporter in over a decade.[164] CBS aired the taped interview later that week. Saddam Hussein later told an FBI interviewer that he once left open the possibility that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction in order to appear strong against Iran.[165][132]

The Iraqi government and military collapsed within three weeks of the beginning of the US-led

Capture and interrogation

In April 2003, Saddam's whereabouts remained in question during the weeks following the fall of Baghdad and the conclusion of the major fighting of the war. Various sightings of Saddam were reported in the weeks following the war, but none were authenticated. At various times Saddam released audio tapes promoting popular resistance to his ousting.

Saddam was placed at the top of the US list of most-wanted Iraqis. In July 2003, his sons Uday and Qusay and 14-year-old grandson Mustapha were killed in a three-hour gunfight with US forces in Mosul with US forces.[167][168]

On 13 December 2003, in

Saddam was shown with a full beard and hair longer than his familiar appearance. He was described by US officials as being in good health. Bremer reported plans to put Saddam on trial, but claimed that the details of such a trial had not yet been determined. Iraqis and Americans who spoke with Saddam after his capture generally reported that he remained self-assured, describing himself as a "firm, but just leader."[171]

British tabloid newspaper

The guards at the Baghdad detention facility called their prisoner "Vic", which stands for "Very Important Criminal" and let him plant a small garden near his cell. The nickname and the garden are among the details about the former Iraqi leader that emerged during a March 2008 tour of the Baghdad prison and cell where Saddam slept, bathed, kept a journal, and wrote poetry in the final days before his execution; he was concerned to ensure his legacy and how the history would be told. The tour was conducted by US Marine Maj. Gen. Doug Stone, overseer of detention operations for the US military in Iraq at the time. During his imprisonment he exercised and was allowed to have his personal garden; he also smoked his cigars and wrote his diary in the courtyard of his cell.[175]

Trial

On 30 June 2004, Saddam Hussein, held in custody by US forces at the US base "Camp Cropper", along with 11 other senior Ba'athist leaders, was handed over to the interim Iraqi government to stand trial for crimes against humanity and other offences.

A few weeks later, he was charged by the

- Saddam and his lawyers contesting the court's authority and maintaining that he was still the President of Iraq.[178]

- The assassinations and attempted assassinations of several of Saddam's lawyers.

- The replacement of the chief presiding judge midway through the trial.

On 5 November 2006, Saddam was found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death by hanging. Saddam's half-brother, Barzan Ibrahim, and Awad Hamed al-Bandar, head of Iraq's Revolutionary Court in 1982, were convicted of similar charges. The verdict and sentencing were both appealed, but subsequently affirmed by Iraq's Supreme Court of Appeals.[179]

Execution

Saddam was hanged on the first day of Eid ul-Adha, 30 December 2006,[180] despite his wish to be executed by firing squad (which he argued was the lawful military capital punishment, citing his military position as the commander-in-chief of the Iraqi military).[181] The execution was carried out at Camp Justice, an Iraqi army base in Kadhimiya, a neighborhood of northeast Baghdad.

Saudi Arabia condemned Iraqi authorities for carrying on with the execution on a holy day. A presenter from the Al-Ikhbariya television station officially stated: "There is a feeling of surprise and disapproval that the verdict has been applied during the holy months and the first days of Eid al-Adha. Leaders of Islamic countries should show respect for this blessed occasion ... not demean it."[182]

Video of the execution was recorded on a mobile phone and his captors could be heard insulting Saddam. The video was leaked to electronic media and posted on the Internet within hours, becoming the subject of global controversy.[183] It was later claimed by the head guard at the tomb where his remains lay that Saddam's body had been stabbed six times after the execution.[184] Saddam's demeanor while being led to the gallows has been discussed by two witnesses, Iraqi Judge Munir Haddad and Iraqi national security adviser Mowaffak al-Rubaie. The accounts of the two witnesses are contradictory as Haddad describes Saddam as being strong in his final moments whereas al-Rubaie says Saddam was clearly afraid.[185]

Saddam's last words during the execution, "May God's blessings be upon Muhammad and his household. And may God hasten their appearance and curse their enemies." Then one of the crowd repeatedly said the name of the Iraqi Shiite cleric, Moqtada Al-Sadr. Saddam laughed and later said, "Do you consider this manhood?" The crowd shouted, "go to Hell." Saddam replied, "To the hell that is Iraq!?" Again, one of the crowd asked those who shouted to keep quiet for God. Saddam Hussein started recitation of final Muslim prayers, "I bear witness that there is no god but Allah and I testify that Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah." One of the crowd shouted, "The tyrant [dictator] has collapsed!" Saddam said, "May God's blessings be upon Muhammad and his household (family)". He recited the shahada one and a half times, as while he was about to say 'Muhammad' on the second shahada, the trapdoor opened, cutting him off mid-sentence. The rope broke his neck, killing him instantly.[186]

Not long before the execution, Saddam's lawyers released his last letter.[187]

A second unofficial video, apparently showing Saddam's body on a trolley, emerged several days later. It sparked speculation that the execution was carried out incorrectly as Saddam Hussein had a gaping hole in his neck.[188]

Saddam was buried at his birthplace of Al-Awja in Tikrit, Iraq, on 31 December 2006. He was buried 3 km (2 mi) from his sons Uday and Qusay Hussein.[189] His tomb was reported to have been destroyed in March 2015.[190] Before it was destroyed, a Sunni tribal group reportedly removed his body to a secret location, fearful of what might happen.[191]

Personal life and family

- Saddam married his first wife and cousin Sajida Talfah (or Tulfah/Tilfah)[192] in 1963 in an arranged marriage. Sajida is the daughter of Khairallah Talfah, Saddam's uncle and mentor; the two were raised as brother and sister. Their marriage was arranged for Saddam at age five when Sajida was seven. They became engaged in Egypt during his exile, and married in Iraq after Saddam's 1963 return.[193] The couple had five children.[192]

- Izzat Ibrahim ad-Douri's daughter, but later divorced her. The couple had no children.

- Iraqi Republican Guard and the SSO. He was believed to have ordered the army to kill thousands of rebelling Marsh Arabsand was instrumental in suppressing Shi'ite rebellions in the mid-1990s. He was married once and had three children.

- Iraqi Government for allegedly financing and supporting the insurgency of the now banned Iraqi Ba'ath Party.[194][195] The Jordanian royal family refused to hand her over. She was married to Hussein Kamel al-Majidand has had five children from this marriage.

- Rana Hussein (b. 1969), is Saddam's second daughter. She, like her sister, fled to Jordan and has stood up for her father's rights. She was married to Saddam Kamel and has had four children from this marriage.

- Hala Hussein (b. 1972), is Saddam's third and youngest daughter. Very little information is known about her. Her father arranged for her to marry General Kamal Mustafa Abdallah Sultan al-Tikriti in 1998. She fled with her children and sisters to Jordan. In June 2021, an Iraqi court ordered the release of her husband after 18 years in prison.[196]

- Saddam married his second wife, Samira Shahbandar,[192] in 1986. She was originally the wife of an Iraqi Airways executive, but later became the mistress of Saddam. Eventually, Saddam forced Samira's husband to divorce her so he could marry her.[192] After the war, Samira fled to Beirut, Lebanon. She is believed to have been the mother of Saddam's sixth child.[192] Members of Saddam's family have denied this.

- Saddam had allegedly married a third wife, Nidal al-Hamdani, the general manager of the Solar Energy Research Center in the Council of Scientific Research.[197]

- Wafa Mullah Huwaysh is rumored to have married Saddam as his fourth wife in 2002. There is no firm evidence for this marriage. Wafa is the daughter of Abd al-Tawab Mullah Huwaysh, a former minister of military industry in Iraq and Saddam's last deputy Prime Minister.

In August 1995, Raghad and her husband, Hussein Kamel al-Majid, and Rana and her husband, Saddam Kamel al-Majid, defected to Jordan, taking their children with them. They returned to Iraq when they received assurances that Saddam would pardon them. Within three days of their return in February 1996, both of the Kamel brothers were attacked and killed in a gunfight with other clan members who considered them traitors.

In August 2003, Saddam's daughters Raghad and Rana received sanctuary in

Philanthropy

In 1979, Jacob Yasso of

Honors and awards

In 1991, the

He was honored by titles such as "Field Marshal" and "Comrade". Saddam Hussein is one of the recipients of the

Saddam received a number of medals, which were displayed at a museum in

Reception and legacy

Saddam is sometimes accused of a repressive totalitarian government.

During his rule, he implemented various policies and initiatives that some people viewed as beneficial for Iraq and the broader

In the

Cultural depictions of Saddam can be found in various movies, including three documentary movies made on Saddam. Saddam's Tribe, released in 2007, explores the complex relationship between Saddam Hussein and the Albu Nasir tribe, a powerful tribal group in Iraq. In 2008, a TV series based on his life — House of Saddam was released. Irish actor Barry Keoghan will appear in a new movie about Saddam which was announced in 2024.[246] Saddam dominated politics of Iraq for 35 years and developed a cult of personality in the world.

List of government and party positions held

- Head of Iraqi Intelligence Service (1963)

- Vice President of the Republic of Iraq (1968–1979)

- President of the Republic of Iraq (1979–2003)

- Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq (1979–1991 and 1994–2003)

- Head of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council(1979–2003)

- Secretary of the Regional Command (1979–2006)

- Secretary General of the National Command(1989–2006)

- Assistant Secretary of the Regional Command (1966–1979)

- Assistant Secretary General of the National Command (1979–1989)

See also

- House of Saddam

- Saddam Beach

- Saddam Hussein Nagar, Sri Lanka

- Saddam Hussein's novels

- US list of most-wanted Iraqis

- Most-wanted Iraqi playing cards

Notes

- ^ Under his government, this date was his official date of birth. His real date of birth was never recorded, but it is believed to be between 1935 and 1939.[1]

- laqab meaning he was born and raised in, or near, Tikrit. He was commonly referred to as Saddam Hussein, or Saddam for short. The observation that referring to the deposed Iraqi president as only Saddam is derogatory or inappropriate may be based on the assumption that Hussein is a family name, thus The New York Times refers to him as "Mr. Hussein",[6] while Encyclopædia Britannica uses just Saddam.[7]A full discussion can be found in the reference preceding this note.

- Arabic: صدام حسين عبد المجيد التكريتي, Mesopotamian Arabic: [sˤɐdˈdɑːm ɜħˈsɪe̯n];[4] also known mononymously as Saddam.[5][b]

References

- ISBN 978-0-330-39310-2).

- ^ "National Progressive Front". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ISBN 978-1-85743-132-2.

- ^ من الأرشيف: إذاعة أم المعارك 1991م (in Arabic), retrieved 11 January 2023

- ^ Shewchuk, Blair (February 2003). "Saddam or Mr. Hussein?". CBC News.

This brings us to the first, and primary, reason many newsrooms use 'Saddam' – it's how he's known throughout Iraq and the rest of the Middle East.

- ^ Burns, John F. (2 July 2004). "Defiant Hussein Rebukes Iraqi Court for Trying Him". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2004.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein". Encyclopædia Britannica. 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ^ "جريدة الرياض | أحمد حسن البكر رجل المقاومة الأول ضد بريطانيا". 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Baram, Amatzia (8 July 2003). "The Iraqi Tribes and the Post-Saddam System". Brookings. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Not mad, just bad and dangerous". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 November 2002. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Jack, Anderson. "Saddam's Roots an Abusive Childhood". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b Post, Jerrold. "Saddam is Iraq: Iraq is Saddam" (PDF). Maxwell Airforce Base. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ^ Eric Davis, Memories of State: Politics, History, and Collective Identity in Modern Iraq, University of California Press, 2005.

- ISBN 978-0-691-05241-0.

- ^ R. Stephen Humphreys, Between Memory and Desire: The Middle East in a Troubled Age, University of California Press, 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Humphreys, 68

- ISBN 978-0857717641.

- ISBN 978-0312160524.

- ^ Coughlin 2005, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Coughlin 2005, p. 29.

- ISBN 978-1-134-03672-1.

- ^ Sale, Richard (10 April 2003). "Exclusive: Saddam Key in Early CIA Plot". United Press International. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ISBN 9781134036721.

The documentary record is filled with holes. A remarkable volume of material remains classified, and those records that are available are obscured by redactions – large blacked-out sections that allow for plausible deniability. While it is difficult to know exactly what actions were taken to destabilize or overthrow Qasim's regime, we can discern fairly clearly what was on the planning table. We also can see clues as to what was authorized.

- ^ ISBN 9781134036721.

- ISBN 978-1-137-48711-7.

- ^ Coughlin 2005, p. 30.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ISBN 978-0-520-92124-5.

- ISBN 978-0-06-050543-1.

- ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein". Britannica. 29 May 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ISBN 9780857713735.

- ^ For sources that agree or sympathize with assertions of U.S. involvement, see:

- Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon; Middle East Studies Pedagogy Initiative (MESPI) (20 July 2018). "Essential Readings: The United States and Iraq before Saddam Hussein's Rule". Jadaliyya.

CIA involvement in the 1963 coup that first brought the Ba'th to power in Iraq has been an open secret for decades. American government and media have never been asked to fully account for the CIA's role in the coup. On the contrary, the US government has put forward and official narrative riddled with holes–redactions that cannot be declassified for "national security" reasons.

- Citino, Nathan J. (2017). "The People's Court". Envisioning the Arab Future: Modernization in US-Arab Relations, 1945–1967. ISBN 978-1-108-10755-6.

Washington backed the movement by military officers linked to the pan-Arab Ba'th Party that overthrew Qasim in a coup on February 8, 1963.

- Jacobsen, E. (1 November 2013). "A Coincidence of Interests: Kennedy, U.S. Assistance, and the 1963 Iraqi Ba'th Regime". Diplomatic History. 37 (5): 1029–1059. ISSN 0145-2096.

There is ample evidence that the CIA not only had contacts with the Iraqi Ba'th in the early sixties, but also assisted in the planning of the coup.

- Ismael, Tareq Y.; Ismael, Jacqueline S.; Perry, Glenn E. (2016). Government and Politics of the Contemporary Middle East: Continuity and Change (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-1-317-66282-2.

Ba'thist forces and army officers overthrew Qasim on February 8, 1963, in collaboration with the CIA.

- Little, Douglas (14 October 2004). "Mission Impossible: The CIA and the Cult of Covert Action in the Middle East". Diplomatic History. 28 (5): 663–701. ISSN 1467-7709.

Such self-serving denials notwithstanding, the CIA actually appears to have had a great deal to do with the bloody Ba'athist coup that toppled Qassim in February 1963. Deeply troubled by Qassim's steady drift to the left, by his threats to invade Kuwait, and by his attempt to cancel Western oil concessions, U.S. intelligence made contact with anticommunist Ba'ath activists both inside and outside the Iraqi army during the early 1960s.

- Osgood, Kenneth (2009). "Eisenhower and regime change in Iraq: the United States and the Iraqi Revolution of 1958". America and Iraq: Policy-making, Intervention and Regional Politics. ISBN 9781134036721.

Working with Nasser, the Ba'ath Party, and other opposition elements, including some in the Iraqi army, the CIA by 1963 was well positioned to help assemble the coalition that overthrew Qasim in February of that year. It is not clear whether Qasim's assassination, as Said Aburish has written, was 'one of the most elaborate CIA operations in the history of the Middle East.' That judgment remains to be proven. But the trail linking the CIA is suggestive.

- Sluglett, Peter. "The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq's Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of its Communists, Ba'thists and Free Officers (Review)" (PDF). Democratiya. p. 9.

Batatu infers on pp. 985–86 that the CIA was involved in the coup of 1963 (which brought the Ba'ath briefly to power): Even if the evidence here is somewhat circumstantial, there can be no question about the Ba'ath's fervent anti-communism.

- Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

Weldon Matthews, Malik Mufti, Douglas Little, William Zeman, and Eric Jacobsen have all drawn on declassified American records to largely substantiate the plausibility of Batatu's account. Peter Hahn and Bryan Gibson (in separate works) argue that the available evidence does support the claim of CIA collusion with the Ba'th. However, each makes this argument in the course of a much broader study, and neither examines the question in any detail.

- Mitchel, Timothy (2002). Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. ISBN 9780520928251.

Qasim was killed three years later in a coup welcomed and possibly aided by the CIA, which brought to power the Ba'ath, the party of Saddam Hussein.

- ISBN 9780307455628.

The agency finally backed a successful coup in Iraq in the name of American influence.

- Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon; Middle East Studies Pedagogy Initiative (MESPI) (20 July 2018). "Essential Readings: The United States and Iraq before Saddam Hussein's Rule". Jadaliyya.

- ^ For sources that dispute assertions of U.S. involvement, see:

- Gibson, Bryan R. (2015). Sold Out? US Foreign Policy, Iraq, the Kurds, and the Cold War. ISBN 978-1-137-48711-7.

Barring the release of new information, the balance of evidence suggests that while the United States was actively plotting the overthrow of the Qasim regime, it did not appear to be directly involved in the February 1963 coup.

- Hahn, Peter (2011). Missions Accomplished?: The United States and Iraq Since World War I. ISBN 9780195333381.

Declassified U.S. government documents offer no evidence to support these suggestions.

- Barrett, Roby C. (2007). The Greater Middle East and the Cold War: US Foreign Policy Under Eisenhower and Kennedy. ISBN 9780857713087.

Washington wanted to see Qasim and his Communist supporters removed, but that is a far cry from Batatu's inference that the U.S. had somehow engineered the coup. The U.S. lacked the operational capability to organize and carry out the coup, but certainly after it had occurred the U.S. government preferred the Nasserists and Ba'athists in power, and provided encouragement and probably some peripheral assistance.

- West, Nigel (2017). Encyclopedia of Political Assassinations. ISBN 9781538102398.

Although Qasim was regarded as an adversary by the West, having nationalized the Iraq Petroleum Company, which had joint Anglo-American ownership, no plans had been made to depose him, principally because of the absence of a plausible successor. Nevertheless, the CIA pursued other schemes to prevent Iraq from coming under Soviet influence, and one such target was an unidentified colonel, thought to have been Qasim's cousin, the notorious Fadhil Abbas al-Mahdawi who was appointed military prosecutor to try members of the previous Hashemite monarchy.

- Gibson, Bryan R. (2015). Sold Out? US Foreign Policy, Iraq, the Kurds, and the Cold War.

- ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

What really happened in Iraq in February 1963 remains shrouded behind a veil of official secrecy. Many of the most relevant documents remain classified. Others were destroyed. And still others were never created in the first place.

- S2CID 159490612.

Archival sources on the U.S. relationship with this regime are highly restricted. Many records of the Central Intelligence Agency's operations and the Department of Defense from this period remain classified, and some declassified records have not been transferred to the National Archives or cataloged.

- S2CID 159490612.

[Kennedy] Administration officials viewed the Iraqi Ba'th Party in 1963 as an agent of counterinsurgency directed against Iraqi communists, and they cultivated supportive relationships with Ba'thist officials, police commanders, and members of the Ba'th Party militia. The American relationship with militia members and senior police commanders had begun even before the February coup, and Ba'thist police commanders involved in the coup had been trained in the United States.

- ISSN 0145-2096.

- ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-87823-4.

- ^ The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (Princeton 1978).

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- YouTube

- ^ Bay Fang. "When Saddam ruled the day." U.S. News & World Report. 11 July 2004. Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Edward Mortimer. "The Thief of Baghdad." New York Review of Books. 27 September 1990, citing Fuad Matar. Saddam Hussein: A Biography. Highlight. 1990. Archived 23 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-520-92124-5.

- ^ a b Helen Chapin Metz (ed) Iraq: A Country Study: "Internal Security in the 1980s", Library of Congress Country Studies, 1988

- ^ "U.S. Relations With Anti-Saddam Groups" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Saddam Hussein – The blundering dictator". The Economist. 4 January 2007.

- ^ a b "War in Iraq: Not a Humanitarian Intervention". Human Rights Watch. 25 January 2004. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

Having devoted extensive time and effort to documenting [Saddam's] atrocities, we estimate that in the last twenty-five years of Ba'ath Party rule the Iraqi government murdered or 'disappeared' some quarter of a million Iraqis, if not more.

- ^ S2CID 164804585.

First, Faust totally ignores the economy in his analysis. This oversight is remarkable given his attempt to trace how the regime became totalitarian, which, by definition, encompasses all facets of life. ... Second, the comparison with Stalin or Hitler is weak when one takes into consideration how many Iraqis were allowed to leave the country. Although citizens needed to undergo a convoluted and bureaucratic procedure to obtain the necessary papers to leave the country, the fact remains that more than one million Iraqis migrated from Iraq from the end of the Iran–Iraq War in 1988 until the US-led invasion in 2003. Third, religion under Stalin did not function in the same manner as it did in Iraq, and while Faust details how the Shia were not allowed to engage in some of their ceremonies, the average Iraqi was allowed to pray at home and in a mosque. ... it is correct that the security services kept a watch on religious establishments and mosques, but the Iraqi approach is somewhat different from that pursued by Stalin's totalitarianism.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-7415-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ^ CNN, "Hussein was symbol of autocracy, cruelty in Iraq," 30 December 2003. [1]

- ^ a b Humphreys, 78

- ^ Saddam Hussein, CBC News, 29 December 2006

- ^ Jessica Moore, The Iraq War player profile: Saddam Hussein's Rise to Power, PBS Online Newshour Archived 15 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Banking in Iraq – A tricky operation". The Economist. 24 June 2004.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-87823-4.

- ^ Khadduri, Majid. Socialist Iraq. The Middle East Institute, Washington, D.C., 1978.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Timeline: Iran-Arab relations". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Iraq and Kurdish Autonomy on JSTOR" MERIP 1974

- ^ "Iraqi Ambassador Mohamed Sadeg al-Mashat speaks about Kurdish Autonomy" Filmed in 1990.

- ^ "President Saddam Hussein patronises the illiteracy eradication campaign" UNESCO 1980

- ^ "Iraqi's must learn to read! or else" Washington post 1979

- ^ "Iraq's economy: Past, present, future – Iraq | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 3 June 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Iraq's economy: Old obstacles and new challenges". ISPI. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Iraq – Oil, Agriculture, Trade | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Mehdi, Abbas S. (22 June 2003). "The Iraqi Economy under Saddam Hussein: Development or Decline". Middle East Policy. 10 (2): 139–142.

- ^ a b Zainab Salbi (18 March 2013). "Why women are less free 10 years after the invasion of Iraq" CNN, Retrieved April 2024.

- ^ "Evolution of Disability Rights in Iraq" JMU 2015, Retrieved April 2024.

- ^ "Health services in Iraq" University of Edinburgh 2013, Retrieved April 2024.

- ^ "Iraq's Public Healthcare System in Crisis" Enabling Peace, Retrieved April 2024.

- ^ "Safe Under Saddam, Iraqi Jews Fear for Future". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ By (13 May 2003). "THREE DOZEN IRAQI JEWS FEARFUL FOR THEIR SAFETY". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "History". Remember Baghdad. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Safe under Saddam, Iraqi Jews fear for future". Indybay. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "These Iraqi Gnostics Hold Water Sacred. Jordanian Authorities Won't Let Them Near a River". Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "The Plight of Iraq's Mandeans – Mandaean Associations Union – اتحاد الجمعيات المندائية". www.mandaeanunion.com. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Saving Saddam – the sequel?". Jamestown. The Jamestown Foundation. 4 March 2003. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010.

- ^ "Reportaje | El obsequio de Sadam a Franco". El País. 2 March 2003.

- ^ a b c Guitta, Olivier (Fall 2005). "The Chirac Doctrine". The Middle East Quarterly.

- ^ Healy, Jack. "Iraq Court Sentences Tariq Aziz to Death." The New York Times. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz (ed) Iraq: A Country Study: "The West", Library of Congress Country Studies, 1988

- ^ BBC, 1981: Israel bombs Baghdad nuclear reactor, BBC On This Day 7 June 1981 referenced 6 January 2007

- ^ Wistrich, Robert (2002). Muslim Anti-Semitism: A Clear and Present Danger. p. 43.

- ^ Humphreys, 120

- ^ Erik Goldstein, Erik (Dr.). Wars and Peace Treaties: 1816 to 1991. P133.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Iran-Iraq War – Summary, Timeline & Legacy". HISTORY. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55587-262-5, pp. 56–58

- ISBN 978-0-19-005022-1.

- ^ Kevin Woods, James Lacey, and Williamson Murray, "Saddam's Delusions: The View From the Inside", Foreign Affairs, May/June 2006.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Dr. Khalil Ibrahim Al Isa, Iraqi Scientist Reports on German, Other Help for Iraq Chemical Weapons Program, Al Zaman (London), 1 December 2003.

- ^ Dickey, Christopher, Thomas, Evan (22 September 2002). "How Saddam Happened". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Confrontation in the Gulf; U.S. Aid Helped Hussein's Climb; Now, Critics Say, the Bill Is Due The New York Times, 13 August 1990.

- ^ Douglas A. Borer (2003). "Inverse Engagement: Lessons from U.S.-Iraq Relations, 1982–1990". U.S. Army Professional Writing Collection. U.S. Army. Archived from the original on 11 October 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ SIPRI Database Archived 25 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Indicates that of $29,079 million of arms exported to Iraq from 1980 to 1988 the Soviet Union accounted for $16,808 million, France $4,591 million, and China $5,004 million (Info must be entered)

- ^ The Iran-Contra Affair 20 Years On. The National Security Archive (George Washington University), 24 November 2006

- ^ "Iran-Iraq War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ [2] The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds. A Middle East Watch Report: Human Rights Watch 1993.

- ^ "Iraqi Anfal, Human Rights Watch, 1993". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Ethnic Cleansing and the Kurds". Jafi.org.il. 15 May 2005. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Burns, John F. (26 January 2003). "How Many People Has Hussein Killed?". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

The largest number of deaths attributable to Mr. Hussein's regime resulted from the war between Iraq and Iran between 1980 and 1988, which was launched by Mr. Hussein. Iraq says its own toll was 500,000, and Iran's reckoning ranges upward of 300,000. Then there are the casualties in the wake of Iraq's 1990 occupation of Kuwait. Iraq's official toll from American bombing in that war is 100,000—surely a gross exaggeration—but nobody contests that thousands of Iraqi soldiers and civilians were killed in the American campaign to oust Mr. Hussein's forces from Kuwait. In addition, 1,000 Kuwaitis died during the fighting and occupation in their country. Casualties from Iraq's gulag are harder to estimate. Accounts collected by Western human rights groups from Iraqi émigrés and defectors have suggested that the number of those who have 'disappeared' into the hands of the secret police, never to be heard from again, could be 200,000.

- ^ Saddam's Chemical Weapons Campaign: Halabja, 16 March 1988 – Bureau of Public Affairs

- ^ "BBC ON THIS DAY | 16 | 1988: Thousands die in Halabja gas attack". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Halabja, the massacre the West tried to ignore". The Times. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ Hiltermann, Joost R. (17 January 2003). "Halabja – America didn't seem to mind poison gas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "FMFRP 3-203 – Lessons Learned: Iran-Iraq War". Fas.org. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-521-87686-5.

Today, few observers question the assertion that it was Iraq that gassed Halabja.

- ^ R. Stephen Humphreys, Between Memory and Desire: The Middle East in a Troubled Age, University of California Press, 1999, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Humphreys, 105