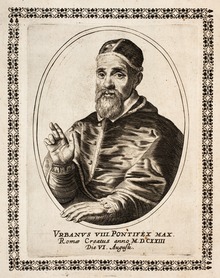

Pope Urban VIII

Innocent X | |

|---|---|

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 24 September 1592 |

| Consecration | 28 October 1604 by Fabio Blondus de Montealto |

| Created cardinal | 11 September 1606 by Paul V |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini 5 April 1568 |

| Died | 29 July 1644 (aged 76) Rome, Papal States |

| Parents | Antonio Barberini & Camilla Barbadoro |

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other popes named Urban | |

Pope Urban VIII (

The massive debts incurred during his pontificate greatly weakened his successors, who were unable to maintain the papacy's longstanding political and military influence in

Biography

Early life

Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini was born in April 1568, the son of Antonio

In 1601, Barberini, through the influence of his uncle, was able to secure from

Papacy

| Papal styles of Pope Urban VIII | ||

|---|---|---|

Reference style | His Holiness | |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness | |

| Religious style | Holy Father | |

| Posthumous style | None | |

Papal election

Barberini was considered someone who could be elected as pope, though there were those such as Cardinal Ottavio Bandini who worked to prevent it. Throughout 29–30 July, the cardinals began an intense series of negotiations to test the numbers as to who could emerge from the conclave as pope, with Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi dismissing Barberini's chances as long as Barberini remained a close ally of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, whose faction Barberini supported. Ludovisi had discussions with Cardinals Odoardo Farnese, Carlo de' Medici and Ippolito Aldobrandini on 30 July about seeing to Barberini's election. The three supported his candidacy and went about securing the support of others, which led to Barberini's election just over a week later.[4] On 6 August 1623, at the papal conclave following the death of Pope Gregory XV, Barberini was chosen as Gregory XV's successor and took the name Urban VIII. His coronation had to be postponed until 29 September 1623 since the new pontiff was ill at the time of his election.

Upon Pope Urban VIII's election, Zeno, the Venetian envoy, wrote the following description of him:[5]

The new Pontiff is 56 years old. His Holiness is tall, dark, with regular features and black hair turning grey. He is exceptionally elegant and refined in all details of his dress; has a graceful and aristocratic bearing and exquisite taste. He is an excellent speaker and debater, writes verses and patronises poets and men of letters.

Activities

Urban VIII's papacy covered 21 years of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), and was an eventful one, even by the standards of the day.

Despite an early friendship and encouragement for his teachings, Urban VIII was responsible for summoning the scientist and astronomer Galileo to Rome in 1633 to recant his work. Urban VIII was opposed to Copernican heliocentrism and he ordered Galileo's second trial after the publication of Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, in which Urban's point of view is argued by the character "Simplicio".

Urban VIII practiced

Urban VIII was a skilled writer of Latin verse, and a collection of scriptural paraphrases as well as original hymns of his composition have been frequently reprinted.

The 1638 papal bull Commissum Nobis protected the existence of

In response to complaints in the

Canonizations and beatifications

Urban VIII canonized five saints during his pontificate:

Canonical coronation

Pope Urban VIII is also known as the first pope who granted a canonical coronation towards a Marian icon. The first icon that was crowned was the La Madonna della Febbre which is enshrined at the sacristy of St. Peter's Basilica. The coronation took place on 1631 making it as the first coronation in the world.

Consistories

The pope created 74 cardinals in eight consistories throughout his pontificate, and this included his nephews Francesco and Antonio, cousin Lorenzo Magalotti, and the pope's own brother Antonio Marcello. He also created Giovanni Battista Pamphili as a cardinal, with Pamphili becoming his immediate successor, Pope Innocent X. The pope also created eight of those cardinals whom he had reserved in pectore.

Policy on private revelation

In the papal bull Sanctissimus Dominus Noster of 13 March 1625, Urban instructed Catholics not to venerate the deceased or represent them in the manner of saints without Church sanction. It required a bishop's approval for the publication of private revelations. Since the nineteenth century, it has become common for books of popular devotion to carry a disclaimer. One read in part: "In obedience to the decrees of Urban the Eighth, I declare that I have no intention of attributing any other than a purely human authority to the miracles, revelations, favours, and particular cases recorded in this book..."[13][14][15]

Politics

Urban VIII's military involvement was aimed less at the restoration of

Urban VIII was the last pope to extend the Papal territory. He fortified

For the purposes of making cannon and the baldacchino in St Peter's, massive bronze girders were pillaged from the portico of the Pantheon leading to the well known lampoon: quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini, "what the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did."[10]

Patron of the arts

Urban VIII expended vast sums bringing polymaths like

The Barberini patronised painters such as

Another such acquisition, in a vast collection, was the purchase of the 'Barberini vase'. This was allegedly found at the mausoleum of the Roman Emperor Severus Alexander and his family at Monte Del Grano. The discovery of the vase is described by Pietro Santi Bartoli and referenced on page 28 of a book on The Portland Vase.[17] Pietro Bartoli indicates that the vase contained the ashes of the Roman Emperor. However, this together with the interpretations of the scenes depicted on it are the source of countless theories and disputed 'facts'. The vase remained in the Barberini family collection for some 150 years before passing through the hands of Sir William Hamilton Ambassador to the Royal Court in Naples. It was later sold to the Duke of Portland, and has subsequently been known as the Portland Vase. Following catastrophic damage, this glass vase (1-25BC) has been reconstructed three times and resides in the British Museum. The Portland vase itself was borrowed and near copied by Josiah Wedgwood who appears to have added modesty drapery. The vase formed the basis of Jasperware.

Later life

A consequence of these military and artistic endeavours was a massive increase in papal debt. Urban VIII inherited a debt of 16 million scudi, and by 1635 had increased it to 28 million.

According to contemporary

With the Spanish plan having failed, by 1640 the debt had reached 35 million scudi, consuming more than 80% of annual papal income in interest repayments.[19]

Death and legacy

Urban VIII's death on 29 July 1644 is said to have been hastened by chagrin at the result of the Wars of Castro. Because of the costs incurred by the city of Rome to finance this war, Urban VIII became immensely unpopular with his subjects.

On his death, the bust of Urban VIII that lay beside the

Following his death, international and domestic machinations resulted in the papal conclave not electing Cardinal

Portrayals in fiction

Urban VIII is a recurring character in the

See also

- Barberini

- Wars of Castro

- Portrait of Maffeo Barberini

- Cardinals created by Urban VIII

- Pontificio Collegio Urbano de Propaganda Fide

- Palazzo Barberini ai Giubbonari

References

- ^ Barton 1964, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Ott 1912.

- ^ Keyvanian 2005, p. 294.

- ^ "Sede Vacante 1623". 27 September 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Pirie, Valérie (1935). The Triple Crown: An Account of the Papal Conclaves from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day. p. 159.

- ^ "Urban Viii - Barberini and Rome". Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ History of the popes; their church and state (Volume III) by Leopold von Ranke (Wellesley College Library, reprint; 2009)

- ^ Mooney 1910.

- ^ Joel S. Panzer, The Popes and Slavery, Staten Island, New York, Society of St. Paul, 1996, pp.89-91.

- ^ a b van Helden, Al (1995). "The Galileo Project". Rice University. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ^ Buescher 2017.

- ^ The Popes and Tobacco 1910, pp. 612–613.

- ISBN 9780195382020. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ISBN 9780812290288.

- ISBN 9781618904614.

- ^ Collins 2009, p. 382.

- OCLC 54960357.

- ^ a b Pope Alexander the Seventh and the College of Cardinals by John Bargrave, edited by James Craigie Robertson (reprint; 2009)

- ISBN 978-0-300-09165-6.

- ^ Ernesta Chinazzi, Sede Vacante per la morte del Papa Urbano VIII Barberini e conclave di Innocenzo X Pamfili, Rome, 1904, 13.

Sources

- Barton, Eleanor Dodge (1964). "Further Notes on the Barberini Tapestries". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 62 (329). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 114–118.

- Buescher, John B. (9 November 2017). "In the Habit: A History of Catholicism and Tobacco". The Catholic World Report. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- Collins, Roger (2009). Keepers of the Keys of Heaven: A History of the Papacy. Basic Books.

- Keyvanian, Carla (2005). "Concerted Efforts: The Quarter of the Barberini Casa Grande in Seventeenth-Century Rome". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 64 (3): 292–311. JSTOR 25068166.

- Mooney, James (1910). "Catholic Encyclopedia Volume VII". Robert Appleton Company, New York. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- Ott, Michael T. (1912). "Pope Urban VIII". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. XV. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- "The Popes and Tobacco". American Ecclesiastical Review. 42 (5): 612–613. May 1910.

Works

- Constitutio contra astrologos iudiciarios (in Italian). Roma: eredi Vittorio Benacci. 1631.

External links

- Italian Academies Themed Collection—British Library. Includes information about Barbernini's membership of Italian academies, and of his links with other intellectuals of his time