Chlormethine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

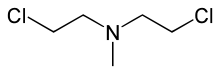

| IUPAC name

2-Chloro-N-(2-chloroethyl)-N-methylethanamine

| |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.000.110 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Mechlorethamine |

PubChem CID

|

|

RTECS number

|

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2810 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H11Cl2N | |

| Molar mass | 156.05 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | Fishy, ammoniacal |

| log P | 0.91 |

| Pharmacology | |

| D08AX04 (WHO) L01AA05 (WHO) | |

| |

| |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| <1 minute | |

| 50% (Kidney) | |

| Legal status | |

| Related compounds | |

Related amines

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Chlormethine (

Mechlorethamine belongs to the group of nitrogen mustard alkylating agents.[4][5][6]

Uses

It has been derivatized into the

Another use of chlormethine is in the synthesis of pethidine (meperidine).[12]

Side effects and toxicity

Mechlorethamine is a highly toxic medication, especially for women who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or of childbearing age.[13][14] At high enough levels, exposure can be fatal.[6]

The adverse effects of mechlorethamine depend on the formulation.[15] When used in chemical warfare, it can cause immunosuppression and damage to mucous membranes of the eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. Mucous membranes and damp or damaged skin are more affected by exposure to HN-2. Though symptoms of exposure are generally delayed, the DNA damage it causes occurs very quickly. More serious exposures cause symptoms to develop sooner. Eye symptoms develop first, in the first 1–2 hours (severe exposure) or 3–12 hours (mild to moderate exposure) followed by airway (2-6/12–24 hours) and skin symptoms (6–48 hours). Hot, humid weather shortens the latent (symptom-free) period.[6]

Symptoms of toxic exposure to HN-2 vary based on the route of exposure. Eye exposure causes lacrimation (tear production), burning, irritation, itching, a feeling of grittiness or dryness, blepharospasm (spasms of the eyelid), and miosis (pinpoint pupils). More severe cases cause edema (swelling from fluid accumulation) in the eyelids, photophobia (extreme sensitivity to light), severe pain, corneal ulceration, and blindness.[6]

Inhalation of chlormethine damages the upper and lower airways sequentially, with more severe exposures causing faster damage that afflicts lower parts of the respiratory tract. Early symptoms include

Skin exposure mainly causes erythema (redness) and vesication (blistering) at first, but absorption through the skin causes systemic toxicity. In cases where more than 25% of the skin is affected, fatal exposure is likely to have occurred.[6]

Though ingestion is uncommon, if mechlorethamine is swallowed it causes severe chemical burns to the gastrointestinal tract and concomitant nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hemorrhage.[6]

Long-term effects of acute or chronic chlormethine exposure are caused by damage to the immune system. White blood cell counts drop, increasing the risk of infection, and red blood cell and platelet counts may also drop due to bone marrow damage. Chronic eye infections may result from exposure, but blindness is temporary. Long-term effects on the respiratory system include anosmia (inability to smell), ageusia (inability to taste), inflammation, chronic infections, fibrosis, and cancer. Skin that has been damaged by HN2 can change pigmentation or become scarred, and may eventually develop cancer.[6]

History

The effect of vesicant (blister) agents in the form of mustard gas (sulfur mustard, Bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide) on bone marrow and white blood cells had been known since the First World War.[16] In 1935 several lines of chemical and biological research yielded results that would be explored after the start of the Second World War. The vesicant action of a family of chemicals related to the sulfur mustards, but with nitrogen substituting for sulfur was discovered—the "nitrogen mustards" were born.[17] The particular nitrogen mustard chlormethine (mechlorethamine) was first synthesized.[18] And the action of sulfur mustard on tumors in laboratory animals was investigated for the first time.[19]

After the US entry into the Second World War the nitrogen mustards were candidate chemical warfare agents and research on them was initiated by the Office of Scientific Research and Development (

The next year the Chicago group, led by Leon O. Jacobson, conducted trials with HN2 (chlormethine) which was the only agent in this group to see eventual clinical use. Wartime secrecy prevented any of this ground-breaking work on chemotherapy from being published, but papers were released once wartime secrecy ended, in 1946.[24]

Chemistry

Chlormethine is combustible and becomes explosive under extreme conditions. It can react with metals to form gaseous hydrogen.[6]

References

- ^ a b c "Ledaga". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Ledaga EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- PMID 10746948.

- ^ "Chapter 3: Principles of Oncologic Pharmacotherapy". Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "CDC - The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database: Blister Agent: NITROGEN MUSTARD HN-2 - NIOSH". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- S2CID 22909007.

- ^ Medline (2012). Mechlorethamine. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a682223.html Archived 2016-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lindahl LM, Fenger-Gron M, Iversen L. Topical nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides or parapsoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Feb;27(2):163-8.

- ^ Galper SL, Smith BD, Wilson LD. Diagnosis and management of mycosis fungoides. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010 May;24(6):491-501.

- ^ Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, Pandya AG, Strober BE, Olsen EA, Hull CM, Knobler EH, Rook AH, Kim EJ, Naylor MF, Adelson DM, Kimball AB, Wood GS, Sundram U, Wu H, Kim YH. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Jan;149(1):25-32.

- PMID 660515.

- ^ Recordati Rare Diseases Inc. (2013). Mustargen Package Insert. Retrieved from https://www.drugs.com/pro/mustargen.html Archived 2018-09-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (2013) Valchlor Package Insert. Retrieved from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/202317lbl.pdf Archived 2021-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mustargen Archived 2018-09-20 at the Wayback Machine and Valchlor Archived 2021-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- from the original on 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- .

- .

- .

- PMID 3891698.

- PMID 17751251.

- PMID 13947966.

- PMID 21247779.

- PMID 20997209.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link