History of the Jews in Europe

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of Auschwitz , May 1944 |

The history of the Jews in Europe spans a period of over two thousand years. Jews, an Israelite tribe from Judea in the Levant,[1][2][3][4] began migrating to Europe just before the rise of the Roman Empire (27 BCE). Although Alexandrian Jews had already migrated to Rome, a notable early event in the history of the Jews in the Roman Empire was the 63 BCE siege of Jerusalem.

Jews have had a significant presence in European cities and countries since the fall of the Roman Empire, including Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, and Russia. In Spain and Portugal in the late fifteenth century, the monarchies forced Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave and they established offices of the Inquisition to enforce Catholic orthodoxy of converted Jews. These actions shattered Jewish life in Iberia and saw mass migration of Sephardic Jews to escape religious persecution. Many resettled in the Netherlands and re-judaized, starting in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In the religiously tolerant, Protestant Dutch Republic Amsterdam prospered economically and as a center of Jewish cultural life, the "Dutch Jerusalem". Ashkenazi Jews lived in communities under continuous rabbinic authority. In Europe Jewish communities were largely self-governing autonomous under Christian rulers, usually with restrictions on residence and economic activities. In Poland, from 1264 (from 1569 also in Lithuania as part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), under the Statute of Kalisz until the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, Jews were guaranteed legal rights and privileges. The law in Poland after 1264 (in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in consequence) toward Jews was one of the most inclusive in Europe. The French Revolution removed legal restrictions on Jews, making them full citizens. Napoleon implemented Jewish emancipation as his armies conquered much of Europe. Emancipation often brought more opportunities for Jews and many integrated into larger European society and became more secular rather remaining in cohesive Jewish communities.

The pre-

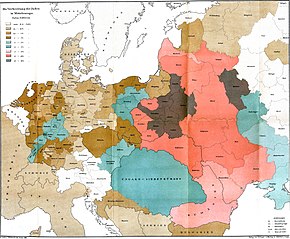

The Jewish population of Europe in 2010 was estimated to be approximately 1.4 million (0.2% of the European population), or 10% of the world's Jewish population.[6] In the 21st century, France has the largest Jewish population in Europe,[6][10] followed by the United Kingdom, Germany, Russia and Ukraine.[10] Prior to the Holocaust, Poland had the largest Jewish population in Europe, as a percentage of its population. This was followed by Lithuania, Hungary, Latvia and Romania.[11]

Ancient period

At the commencement of the reign of

Many Jews migrated to Rome from Alexandria as a result of the close trade relations between the two cities. When the Roman Empire captured Jerusalem in 63 BCE, thousands of Jewish prisoners of war were brought from Judea to Rome, where they were sold into slavery. After they gained their freedom, these Jews permanently settled in Rome on the right bank of the Tiber as traders.[16][17] Following the capture of Jerusalem by the forces of Herod the Great with assistance from Roman forces in 37 BCE, it is likely that Jews were again taken to Rome as slaves. It is known that Jewish war captives were sold into slavery after the suppression of a minor Jewish revolt in 53 BCE, and some were probably taken to southern Europe.[18]

The Roman Empire period presence of Jews in modern-day Croatia dates to the 2nd century, in Pannonia to the 3rd to 4th century. A finger ring with a menorah depiction found in Augusta Raurica (Kaiseraugst, Switzerland) in 2001 attests to Jewish presence in Germania Superior.[19] Evidence in towns north of the Loire or in southern Gaul date to the 5th century and 6th centuries.[20] By late antiquity, Jewish communities were found in modern-day France and Germany.[21][22] In the Taman Peninsula, modern day Russia, Jewish presence dates back to the first century. Evidence of Jewish presence in Phanagoria includes tombstones with carved images of the menorah and inscriptions with references to the synagogue.[23]

Middle Ages

The early medieval period was a time of flourishing Jewish culture. Jewish and Christian life evolved in 'diametrically opposite directions' during the final centuries of Roman empire. Jewish life became autonomous, decentralized, community-centered. Christian life became a hierarchical system under the supreme authority of the Pope and the Roman Emperor.[30]

Jewish life can be characterized as democratic. Rabbis in the Talmud interpreted Deut. 29:9, "your heads, your tribes, your elders, and your officers, even all the men of Israel" and "Although I have appointed for you heads, elders, and officers, you are all equal before me" (Tanhuma) to stress political shared power. Shared power entailed responsibilities: "you are all responsible for one another. If there be only one righteous man among you, you will all profit from his merits, and not you alone, but the entire world...But if one of you sins, the whole generation will suffer."[31]

Early Middle Ages

In the

European Jews were at first concentrated largely in southern Europe. During the

High Middle Ages

Persecution of Jews in Europe increased in the

In relations with Christian society, they were protected by kings, princes and bishops, because of the crucial services they provided in three areas: finance, administration, and medicine. Christian scholars interested in the Bible would consult with Talmudic rabbis. All of this changed with the reforms and strengthening of the Roman Catholic Church and the rise of competitive middle-class, town dwelling Christians. By 1300, the friars and local priests were using the Passion Plays at Easter time, which depicted Jews, in contemporary dress, killing Christ, to teach the general populace to hate and murder Jews. It was at this point that persecution and exile became endemic. As a result of persecution, expulsions and massacres carried out by the Crusaders, Jews gradually migrated to Central and Eastern Europe, settling in Poland, Lithuania, and Russia, where they found greater security and a renewal of prosperity.[36][41]

Late Middle Ages

In the Late Middle Ages, in the mid-14th century, the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe, annihilating 30–50 percent of the population.[42] It is an oft-told myth that due to better nutrition and greater cleanliness, Jews were not infected in similar numbers; Jews were indeed infected in numbers similar to their non-Jewish neighbors[43] Yet they were still made scapegoats. Rumors spread that Jews caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells[by whom?]. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence. Although Pope Clement VI tried to protect them with his 6 July 1348 papal bull and another papal bull in 1348, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt alive in Strasbourg, where the plague had not yet reached the city.[44] Christian accusations of host desecration and blood libels were made against Jews.[45] Pogroms followed, and the destruction of Jewish communities yielded the funds for many Pilgrimage churches or chapels throughout the Middle Ages (e.g. Saint Werner's Chapels of Bacharach, Oberwesel, Womrath; Deggendorfer Gnad in Bavaria).

Jewish survival in the face of external pressures from the Roman Catholic empire and the Persian Zoroastrian empire is seen as 'enigmatic' by historians.[46]

Salo Wittmayer Baron credits Jewish survival to eight factors:

- Messianic faith: Belief in an ultimately positive outcome and restoration to them of the Land of Israel.

- The doctrine of the World-to-Come increasingly elaborated: Jews were reconciled to suffering in this world, which helped them resist outside temptations to convert.

- Suffering was given meaning through hope-inducing interpretation of their history and their destiny.

- The doctrine of martyrdom and inescapability of persecution transformed it into a source of communal solidarity.

- Jewish daily life was very satisfying. Jews lived among Jews. In practice, in a lifetime, individuals encountered overt persecution only on a few dramatic occasions. Jews mostly lived under discrimination that affected everyone, and to which they were habituated. Daily life was governed by a multiplicity of ritual requirements, so that each Jew was constantly aware of God throughout the day. "For the most part, he found this all-encompassing Jewish way of life so eminently satisfactory that he was prepared to sacrifice himself...for the preservation of its fundamentals."[47] Those commandments for which Jews had sacrificed their lives, such as defying idolatry, not eating pork, observing circumcision, were the ones most strictly adhered to.[48]

- The corporate development and segregationist policies of the late Roman empire and Persian empire, helped keep Jewish community organization strong.

- Talmud provided an extremely effective force to sustain Jewish ethics, law and culture, judicial and social welfare system, universal education, regulation of strong family life and religious life from birth to death.

- The concentration of Jewish masses within 'the lower middle class',[49] with the middle class virtues of sexual self-control. There was a moderate path between asceticism and licentiousness. Marriage was considered to be the foundation of ethnic, and ethical, life.

Outside hostility only helped cement Jewish unity and internal strength and commitment.

Jews in Iberia under Islamic rule

The Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain refers to a period of history during the Muslim rule of Iberia in which Jews were generally accepted in society and Jewish religious, cultural and economic life blossomed. This "Golden Age" is variously dated from the 8th to 12th centuries.

Al-Andalus was a key center of Jewish life during the Middle Ages, producing important scholars and one of the most stable and wealthy Jewish communities. A number of famous Jewish philosophers and scholars flourished during this time, most notably Maimonides.

Early Modern period

The

Catholic Spain and Portugal

The fall of

Amsterdam as the "Dutch Jerusalem"

When the Protestant Dutch Republic revolted against Catholic Spain in what became the Eighty Years' War, Portuguese and Spanish Jews forced to convert to Catholicism (conversos or Marranos) began migrating to the northern provinces of the Netherlands.[53] Religious tolerance, the freedom of conscience to practice one's religion without impediment, was a core Dutch Protestant value. These Sephardic migrants established a thriving community in Amsterdam, which became known as the "Dutch Jerusalem"[54] Three Sephardic congregations merged and built a huge synagogue, the Portuguese Synagogue, opening in 1675. Prosperous Jewish merchants built opulent houses among successful non-Jewish merchants, since there was no restriction of Jews to particular residential quarters. The Iberian Jews strongly identified both as Jews and as ethnically Portuguese, calling themselves "Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation".[55] Amsterdam's Portuguese Jewish merchants created a huge trade network in the Americas, with Portuguese Jews emigrating to the Caribbean and to Brazil.[56] Ashkenazi Jews settled in Amsterdam as well but were generally poorer than the Sephardim and dependent of their charity. However, Amsterdam's prosperity faltered in the late seventeenth century, as did the fortunes and number of Sephardic Jews, while the Ashkenazi Jews' numbers continued to rise and have dominated the Netherlands ever since.

England Re-opens to Jewish Settlement

England expelled its small Jewish population (ca. 2,000) in 1290, but in the seventeenth century, prominent Portuguese Jewish rabbi

Poland as a center of the Jewish community

The most prosperous period for Polish Jews began following this new influx of Jews with the reign of

By 1551, Polish Jews were given permission to choose their own Chief Rabbi. The Chief Rabbinate held power over law and finance, appointing judges and other officials. Other powers were shared with local councils. The Polish government permitted the Rabbinate to grow in power and used it for tax collection purposes. Only 30% of the money raised by the Rabbinate went to the Jewish communities. The rest went to the Crown for protection. In this period Poland-Lithuania became the main center for Ashkenazi Jewry, and its

Moses Isserles (1520–1572), an eminent Talmudist of the 16th century, established his yeshiva in Kraków. In addition to being a renowned Talmudic and legal scholar, Isserles was also learned in Kabbalah, and studied history, astronomy, and philosophy.

The culture and intellectual output of the Jewish community in Poland had a profound impact on Judaism as a whole. Some Jewish historians have recounted that the word Poland is pronounced as Polania or Polin in

In the first half of the 16th century the seeds of Talmudic learning had been transplanted to Poland from

Growth of Hasidism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

The decade from the

Into this time of

Modern era, 1750 to 1930

Jewish emancipation

As part of the egalitarian principles of the French Revolution, Jews became full citizens without restrictions. Napoleon expanded the egalitarian principles in the places his armies conquered. Even in the Netherlands, which had a well-established tradition of religious tolerance, when it came under French sway, Jewish religious leaders no longer could exercise authority in an autonomous community. The so-called Jewish question was active exploration of a potentially new vision of the Jews' place in European states. The Jewish Enlightentment produced an important body of knowledge and speculation on a range of questions regarding Jewish identity. A leading figure was German Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn.

Changing conditions for Jewish populations

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Russia was the European country with the largest Jewish population, following annexation of

Difficult conditions in Eastern Europe and the possibility of bettering their lot elsewhere triggered Jewish migration to Western Europe, particularly where Jews were already living in conditions of

In Hungary the early 19th century, in the reform age the progressive nobility set many goals of innovation, such as the emancipation of the Hungarian Jewry. Hungarian Jews were able to play a part in the economy by assuming an important role in industrial and trading development. For example, Izsák Lőwy (1793–1847) founded his leather factory on a previously purchased piece of land in 1835, and created a new, modern town, with independent authority, religious equality and industrial freedom independent from the guilds. The town, which was given the name Újpest (New Pest), soon became a very important settlement. Its first synagogue was built in 1839. (Újpest, the current capital's 4th district is in the northern part of Budapest. During the time of the Holocaust 20,000 Jews were deported from here.) Mór Fischer Farkasházi (1800–1880) founded his world-famous porcelain factory in Herend in 1839, its fine porcelains decorated, among others, Queen Victoria's table.[citation needed]

In the

Jewish emigration from Europe

Starting in the 19th century after Jewish emancipation, European Jews left the continent in huge numbers, especially for the United States and some other countries, to pursue better opportunity and to escape religious persecution, including

Zionism

The movement of

Herzl infused political Zionism with a new and practical urgency. He brought the World Zionist Organization into being and, together with Nathan Birnbaum, planned its First Congress at Basel in 1897.[72] For the first four years, the World Zionist Organization (WZO) met every year, then, up to the Second World War, they gathered every second year. Since the war, the Congress has met every four years.

Religious organizations

In 1868/69, three major Jewish organizations were founded: the largest group were the more modern congressional or neolog Jews, the very traditional minded joined the orthodox movement, and the conservatives formed the status quo organization. The neolog Grand Synagogue had been built earlier, in 1859, in the Dohány Street. The main status quo temple, the nearby Rumbach Street Synagogue was constructed in 1872. The Budapest orthodox synagogue is located on Kazinczy Street, along with the orthodox community's headquarters and mikveh.

In May 1923, in the presence of President Michael Hainisch, the First World Congress of Jewish Women was inaugurated at the Hofburg in Vienna, Austria.[73]

World War II and the Holocaust

The Holocaust of the Jewish people (from the Greek ὁλόκαυστον (holókauston): holos, "completely" and kaustos, "burnt"), also known as Ha-Shoah (

Post World War II

Demographics

The Jewish population of Europe in 2010 was estimated to be approximately 1.4 million (0.2% of the European population) or 10% of the world's Jewish population.[6] In the 21st century, France has the largest Jewish population in Europe,[6][10] followed by the United Kingdom, Germany, Russia and Ukraine.[10]

Jewish ethnic subdivisions of Europe

- Armenian Jews

- Ashkenazim(Yiddish speaking Jews)

- Crimean Karaites and Krymchaks (Crimean Jews)

- Georgian Jews

- Italian Jews (also known as Bnei Roma)

- Mizrahi Jews

- Romaniotes(Greek Jews)

- Sephardim(Spanish/Portuguese Jews)

- Turkish Jews

See also

- Statute of Kalisz

- History of Europe

- Jewish culture

- Jewish diaspora

- Jewish history

- The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

Notes

- ^ Jared Diamond (1993). "Who are the Jews?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2010. Natural History 102:11 (November 1993): 12–19.

- PMID 10801975.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (9 May 2000). "Y Chromosome Bears Witness to Story of the Jewish Diaspora". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-0120884926.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ [1] Jewish Gen – The Given Names Data Base, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Europe's Jewish population".

- ^ "Estimated Number of Jews Killed in the Final Solution".

- ^ "Holocaust | Basic questions about the Holocaust". www.projetaladin.org.

- ^ Dawidowicz, Lucy. The War Against the Jews, Bantam, 1986. p. 403

- ^ a b c d "Jews". Pew Research Center. December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Jewish Population of Europe in 1933: Population Data by Country". Holocaust Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ The Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture, p. 3

- Walter de GruyterGmbH & Co KG

- ^ a b Josephus Flavius, Antiquities, xi.v.2

- ^ E. Mary Smallwood (2008) The Diaspora in the Roman period before CE 70. In: The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 3. Editors Davis and Finkelstein.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph and Schulim, Oscher: Rome – Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Davies, William David; Finkelstein, Louis; Horbury, William; Sturdy, John; Katz, Steven T.; Hart, Mitchell Bryan; Michels, Tony; Karp, Jonathan; Sutcliffe, Adam; Chazan, Robert: The Cambridge History of Judaism: The early Roman period, p. 168 (1984), Cambridge University Press

- ^ The Jews Under Roman Rule: From Pompey to Diocletian and they lived in most countries in Europe : a Study in Political Relations, p. 131

- ^ The Kaiseraugst Menorah Ring. Jewish Evidence from the Roman Period in the Northern Provinces Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine Augusta Raurica 2005/2, accessed November 24, 2009. (German)

- ^ Eli Barnavi: The Beginnings of European Jewry. The genesis of Ashkenazi identity Archived 2008-01-03 at the Wayback Machine My Jewish Learning, accessed November 24, 2009.

- ^ "Germany: Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ "Archäologische Zone – JĂźdisches Museum". Museenkoeln.de. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ http://phanagoria.info/upload/iblock/775/Phanagoriya_English_web.pdf Page 16-19

- Norman F. Cantor, The Civilization of the Middle Ages, 1993, "Culture and Society in the First Europe", pp. 185ff.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopaedia 2007. Europe. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ISBN 0-19-530429-2. pp. 46–48

- ^ a b Grosser, P.E. and E.G. Halperin. "Jewish Persecution – History of AntiSemitism – Lesser Known Highlights of Jewish International Relations In The Common Era". simpletoremember.com. SimpleToRemember.com – Judaism Online. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ ISBN 0806507039. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Salo Wittmayer Baron, "A Social and Religious History of the Jews," Volume II, Ancient Times, Part II. p. 200 Jewish Publication Society of America, 1952.

- ^ Salo Wittmayer Baron, "A Social and Religious History of the Jews", Volume II, Ancient Times, Part II. p. 200 Jewish Publication Society of America, 1952.

- ISBN 90-04-10846-7

- ^ Ben-Jacob, Abraham (1985), "The History of the Babylonian Jews".

- ^ Grossman, Abraham (1998), "The Sank of Babylon and the Rise of the New Jewish Centers in the 11th Century Europe"

- ^ Frishman, Asher (2008), "The First Asheknazi Jews".

- ^ a b Ashkenazi – Definition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Nina Rowe, The Jew, the Cathedral and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the 13th Century Cambridge University Press, 2011 p. 30.

- ^ Why the Jews? Holocaust Center of the United Jewish Federation of Pittsburgh, accessed November 24, 2009.

- )

- ^ Woodworth, Cherie. "Where Did the East European Jews Come From?" (PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ISBN 0-7432-2688-7Free Press 2004

- PMID 24806459.

- ^ Jane S. Gerber, "The Jews of Spain," p. 112 The Free Press, 1992.

- ^ See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in L'Histoire magazine, n°310, June 2006, p. 47 (in French)

- ISBN 978-0-313-32865-7.

- ^ Salo Wittmayer Baron, "A Social and Religious History of the Jews," Volume II, Ancient Times, Part II. p. 215 Jewish Publication Society of America, 1952.

- ^ Baron, p. 216

- ^ Baron, pp. 216–217

- ^ Baron, p. 217

- ^ Cohen, R.I. Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1998

- ^ Ettinger, S. "The Beginning of Change in the Attitude of European Society Towards the Jews", Scripta Hierosolymitana 7 (1961), 192-219

- ^ Kaplan, Yosef. "For Whom did Emanuel de Witte Paint his Three Pictures of the Sephardic Synagogue of Amsterdam?" Studia Rosenthaliana 32, 2 (1998) 133-154

- ^ Swetschinski, Daniel M. Reluctant Cosmopolitans: The Portuguese Jews of Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam. London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization 2000, 54-101

- ^ Ridley Haim Herschell. The Voice of Israel, 1845. pg. 27.

- ^ Bodian, Miriam. Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam. Bloomington: Indiana University 1997

- ^ Swetschinski, Daniel M. Reluctant Cosmopolitans, 102-164

- ^ Endelman, Todd M. The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 2002, 15-40

- ^ George Sanford, Historical Dictionary of Poland (2nd ed.) Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, 2003. p. 79.

- ^ "European Jewish Congress – Poland". December 11, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11.

- ^ The Virtual Jewish History Tour – Poland. Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved on 2010-08-22.

- ^ The Pittsburgh Press, October 25, 1915, p. 11

- JSTOR 43189345.

- S2CID 163193494.

- JSTOR 2495871.

- JSTOR 1396423.

- JSTOR 130048.

- ^ Endelman, Todd M. The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000, 41-182

- ^ Sarna, Jonathan D. American Judaism: A History. Second edition. New Haven: Yale University Press 2019, 65-68

- ^ Theodor Herzl: The Jewish State, English translation Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine WZO, The Hagshama Department, accessed November 24, 2009.

- ^ Theodor Herzl: Altneuland, English translation Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine WZO, The Hagshama Department, accessed November 24, 2009.

- ^ Hannah Arendt, 1946, ' Der Judenstaat 50 years later', also published in: Hannah Arendt, The Jew as pariah, NY, 1978, N. Finkelstein, 2002, Image and reality of the Israel-Palestine conflict, 2nd ed., pp. 7–12

- ^ First Zionist Congress: Basel 29–31 August 1897 Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Herzl Museum, Jerusalem, accessed November 24, 2009.

- ISBN 978-3-205-99137-3.

- ^ a b DellaPergola, Sergio. "World Jewish Population, 2010" (PDF). The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-26. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Turkish Jews#Notable Turkish JewsTurkish

Further reading

- Bartal, Israel (2011). The Jews of Eastern Europe, 1772–1881. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0081-2.

- Bodian, Miriam. Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1997.

- Haumann, Heiko (2002). A History of East European Jews. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-26-8.

- Grill, Tobias, ed. (2018). Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe: Shared and Comparative Histories. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. JSTOR j.ctvbkk4bs.

- Kaplan, Yosef. "The Self-Definition of the Sephardic Jews of Western Europe and their Relation to the Alien and the Stranger", in: B. R. Gampel (ed.), Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World, 1391-1648, (New York 1997), p. 121-145.

- Karady, Victor. The Jews of Europe in the Modern Era: A Socio-historical Outline. Budapest: Central European University Press 2004.

- Lambert, Nick. Jews and Europe in the Twenty-First Century. London: Vallentine Mitchell 2008.

- Ruderman, David B. (2010). Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3469-3.

- Vital. David. A People Apart: The Jews in Europe 1789-1939. New York: Oxford University Press 1999.

- Wasserstein, Bernard. Vanishing Diaspora: The Jews in Europe since 1945.Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press 1996.