Poland

Republic of Poland Rzeczpospolita Polska (Polish) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Mazurek Dąbrowskiego " | |

| Religion (2021[3] ) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Andrzej Duda | |

| Donald Tusk | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Sejm | |

| Formation | |

| c. 960 | |

| 14 April 966 | |

| 18 April 1025 | |

| 1 July 1569 | |

| 24 October 1795 | |

| 11 November 1918 | |

| 17 September 1939 | |

| 22 July 1944 | |

| 31 December 1989[6] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi)[7][8] (69th) |

• Water (%) | 1.48 (2015)[9] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 122/km2 (316.0/sq mi) (75th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (36th) |

| Currency | Złoty (PLN) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +48 |

| ISO 3166 code | PL |

| Internet TLD | .pl [a] |

| |

Poland,[c] officially the Republic of Poland,[d] is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative voivodeship provinces, covering an area of 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi).[14] Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous member state of the European Union. Warsaw is the nation's capital and largest metropolis. Other major cities include Kraków, Wrocław, Łódź, Poznań, and Gdańsk.

Poland has a

Prehistoric human activity on Polish soil dates to the Lower Paleolithic, with continuous settlement since the end of the Last Glacial Period. Culturally diverse throughout late antiquity, in the early medieval period the region became inhabited by the tribal Polans, who gave Poland its name. The process of establishing proper statehood, which began in 966, coincided with the conversion of a pagan ruler of the Polans to Christianity, under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church. The Kingdom of Poland emerged in 1025, and in 1569 cemented its long-standing association with Lithuania, thus forming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. At the time, the Commonwealth was one of the great powers of Europe, with a uniquely liberal political system which adopted Europe's first modern constitution in 1791.

With the passing of the prosperous Polish Golden Age, the country was partitioned by neighbouring states at the end of the 18th century. Poland regained its independence in 1918 as the Second Polish Republic and successfully defended it in the Polish–Soviet War from 1919 to 1921. In September 1939, the invasion of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union marked the beginning of World War II, which resulted in the Holocaust and millions of Polish casualties. Forced into the Eastern Bloc in the global Cold War, the Polish People's Republic was a founding signatory of the Warsaw Pact. Through the emergence and contributions of the Solidarity movement, the communist government was dissolved and Poland re-established itself as a democratic state in 1989.

Poland is a parliamentary republic, with its bicameral legislature comprising the Sejm and the Senate. It is a developed market and a high-income economy. Considered a middle power, Poland has the sixth-largest economy in the European Union by GDP (nominal) and the fifth-largest by GDP (PPP). It provides a very high standard of living, safety, and economic freedom, as well as free university education and a universal health care system. The country has 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 15 of which are cultural. Poland is a founding member state of the United Nations, as well as a member of the World Trade Organization, OECD, NATO, and the European Union (including the Schengen Area).

Etymology

The native

The country's alternative archaic name is

History

Prehistory and protohistory

The first

The period spanning the

Throughout

Kingdom of Poland

Poland began to form into a recognisable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the

In 1000, at the Congress of Gniezno, Bolesław obtained the right of investiture from Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor, who assented to the creation of additional bishoprics and an archdioceses in Gniezno.[40] Three new dioceses were subsequently established in Kraków, Kołobrzeg, and Wrocław.[42] Also, Otto bestowed upon Bolesław royal regalia and a replica of the Holy Lance, which were later used at his coronation as the first King of Poland in c. 1025, when Bolesław received permission for his coronation from Pope John XIX.[43][44] Bolesław also expanded the realm considerably by seizing parts of German Lusatia, Czech Moravia, Upper Hungary and southwestern regions of the Kievan Rus'.[45]

The transition from

In the first half of the 13th century,

In 1320,

In 1386, Jadwiga of Poland entered a marriage of convenience with

In the Baltic Sea region, the struggle of Poland and Lithuania with the

Poland was developing as a

The 16th century saw

The European Renaissance evoked under Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus a sense of urgency in the need to promote a cultural awakening.[22] During the Polish Golden Age, the nation's economy and culture flourished.[22] The Italian-born Bona Sforza, daughter of the Duke of Milan and queen consort to Sigismund I, made considerable contributions to architecture, cuisine, language and court customs at Wawel Castle.[22]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The

In 1573,

In 1609, Sigismund

Sigismund's long reign in Poland coincided with the

Partitions

The

In 1772, the

In 1791,

Era of insurrections

The Polish people rose several times against the partitioners and occupying armies. An unsuccessful attempt at defending Poland's sovereignty took place in the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising, where a popular and distinguished general Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had several years earlier served under George Washington in the American Revolutionary War, led Polish insurgents.[105] Despite the victory at the Battle of Racławice, his ultimate defeat ended Poland's independent existence for 123 years.[106]

In 1806, an

In 1830,

Second Polish Republic

In the aftermath of

The Second Polish Republic reaffirmed its sovereignty after a series of military conflicts, most notably the Polish–Soviet War, when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on the Red Army at the Battle of Warsaw.[117]

The inter-war period heralded a new era of Polish politics. Whilst Polish political activists had faced heavy censorship in the decades up until

In 1926, the

World War II

World War II began with the

Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution in Europe,

The

Nazi German forces under orders from

In 1945, Poland's borders

Post-war communism

At the insistence of

Despite widespread objections, the new Polish government accepted the Soviet annexation of the pre-war eastern regions of Poland

The new communist government took control with the adoption of the

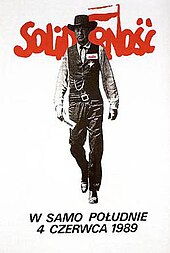

Labour turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity" ("Solidarność"), which over time became a political force. Despite persecution and imposition of martial law in 1981 by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, it eroded the dominance of the Polish United Workers' Party and by 1989 had triumphed in Poland's first partially free and democratic parliamentary elections since the end of the Second World War. Lech Wałęsa, a Solidarity candidate, eventually won the presidency in 1990. The Solidarity movement heralded the collapse of communist regimes and parties across Europe.[155]

Third Polish Republic

A

Poland joined the

In 2011, the ruling

Geography

Poland covers an administrative area of 312,722 km2 (120,743 sq mi), and is the

The country has a coastline spanning 770 km (480 mi); extending from the shores of the Baltic Sea, along the

The mountainous belt in the extreme south of Poland is divided into two major

Poland's

Climate

The climate of Poland is

There is a considerable fluctuation in day-to-day weather and the arrival of a particular season can differ each year.[183] Climate change and other factors have further contributed to interannual thermal anomalies and increased temperatures; the average annual air temperature between 2011 and 2020 was 9.33 °C (48.8 °F), around 1.11 °C higher than in the 2001–2010 period.[185] Winters are also becoming increasingly drier, with less sleet and snowfall.[183]

Biodiversity

The

Around 315,100 hectares (1,217 sq mi), equivalent to 1% of Poland's territory, is protected within 23

Government and politics

Poland is a

Poland's

With the exception of ethnic minority parties, only candidates of political parties receiving at least 5% of the total national vote can enter the Sejm.[199] Both the lower and upper houses of parliament in Poland are elected for a four-year term and each member of the Polish parliament is guaranteed parliamentary immunity.[201] Under current legislation, a person must be 21 years of age or over to assume the position of deputy, 30 or over to become senator and 35 to run in a presidential election.[201]

Members of the Sejm and Senate jointly form the

Administrative divisions

Poland is divided into 16 provinces or states known as voivodeships.[203] As of 2022, the voivodeships are subdivided into 380 counties (powiats), which are further fragmented into 2,477 municipalities (gminas).[203] Major cities normally have the status of both gmina and powiat.[203] The provinces are largely founded on the borders of historic regions, or named for individual cities.[204] Administrative authority at the voivodeship level is shared between a government-appointed governor (voivode), an elected regional assembly (sejmik) and a voivodeship marshal, an executive elected by the assembly.[204]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Law

The

The

Poland has a low

Historically, the most significant Polish legal act is the

Foreign relations

Poland is a

In recent years, Poland significantly strengthened its relations with the United States, thus becoming one of its closest allies and strategic partners in Europe.[222] Historically, Poland maintained strong cultural and political ties to Hungary; this special relationship was recognised by the parliaments of both countries in 2007 with the joint declaration of 23 March as "The Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship".[223]

Military

The Polish Armed Forces are composed of five branches – the

Poland is spending 2% of its GDP on defence, equivalent to approximately US$14.5 billion in 2022, with a slated increase to US$29 billion in 2023.

Compulsory

Security, law enforcement and emergency services

Thanks to its location, Poland is a country essentially free from the threat of natural disasters such as

Law enforcement in Poland is performed by several agencies which are subordinate to the

The

Emergency services in Poland consist of the emergency medical services, search and rescue units of the Polish Armed Forces and State Fire Service. Emergency medical services in Poland are operated by local and regional governments,[241] but are a part of the centralised national agency – the National Medical Emergency Service (Państwowe Ratownictwo Medyczne).[242]

Economy

| GDP (PPP) | $1.801 trillion (2024)[11] |

|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | $844.6 billion (2024)[11] |

| Real GDP growth | 5.3% (2022)[243] |

| CPI inflation | 14.4% (2022)[244] |

| Employment-to-population ratio | 57% (2022)[245] |

| Unemployment | 2.8% (2023)[246] |

Total public debt

|

$340 billion (2022)[247] |

As of 2023[update], Poland's economy and gross domestic product (GDP) is the sixth largest in the European Union by nominal standards and the fifth largest by purchasing power parity. It is also one of the fastest growing within the Union and reached a developed market status in 2018.[248] The unemployment rate published by Eurostat in 2023 amounted to 2.8%, which was the second-lowest in the EU.[246] As of 2023[update], around 62% of the employed population works in the service sector, 29% in manufacturing, and 8% in the agricultural sector.[249] Although Poland is a member of the European single market, the country has not adopted the Euro as legal tender and maintains its own currency – the Polish złoty (zł, PLN).

Poland is the regional economic leader in Central Europe, with nearly 40 per cent of the 500 biggest companies in the region (by revenues) as well as a

Poland has the largest banking sector in Central Europe,[252] with 32.3 branches per 100,000 adults.[253] It was the only European economy to have avoided the recession of 2008.[254] The country is the 20th largest exporter of goods and services in the world.[255] Exports of goods and services are valued at approximately 56% of GDP, as of 2020.[256] In 2019, Poland passed a law that would exempt workers under the age of 26 from income tax.[257]

Tourism

Poland experienced a significant increase in the number of tourists after joining the European Union in 2004.[258][259] With over 21 million international arrivals in 2019, tourism contributes considerably to the overall economy and makes up a relatively large proportion of the country's service market.[260]

Tourist attractions in Poland vary, from the mountains in the south to the sandy beaches in the north, with a trail of nearly every architectural style. The most visited city is

Poland has a 770 km long coastline of the southern Baltic Sea with many wide sandy beaches, which are frequently visited by tourists in the summer season.

Other tourist destinations include the

Transport

Transport in Poland is provided by means of rail, road, marine shipping and air travel. The country is part of EU's Schengen Area and is an important transport hub due to its strategic geographical position in Central Europe.[265] Some of the longest European routes, including the E30 and E40, run through Poland. The country has a good network of highways comprising express roads and motorways. As of August 2023, Poland has the world's 21st-largest road network, maintaining over 5,000 km (3,100 mi) of highways in use.[266]

In 2022, the nation had 19,393 kilometres (12,050 mi) of railway track, the third longest in the European Union after Germany and France.[267] The Polish State Railways (PKP) is the dominant railway operator, with certain major voivodeships or urban areas possessing their own commuter and regional rail.[268] Poland has a number of international airports, the largest of which is Warsaw Chopin Airport.[269] It is the primary global hub for LOT Polish Airlines, the country's flag carrier.[270]

Seaports exist all along Poland's Baltic coast, with most freight operations using Świnoujście, Police, Szczecin, Kołobrzeg, Gdynia, Gdańsk and Elbląg as their base. The Port of Gdańsk is the only port in the Baltic Sea adapted to receive oceanic vessels. Polferries and Unity Line are the largest Polish ferry operators, with the latter providing roll-on/roll-off and train ferry services to Scandinavia.[271]

Energy

The electricity generation sector in Poland is largely fossil-fuel–based. Coal production in Poland is a major source of employment and the largest source of the nation's greenhouse gas emissions.[272] Many power plants nationwide use Poland's position as a major European exporter of coal to their advantage by continuing to use coal as the primary raw material in the production of their energy. The three largest Polish coal mining firms (Węglokoks, Kompania Węglowa and JSW) extract around 100 million tonnes of coal annually.[273] After coal, Polish energy supply relies significantly on oil—the nation is the third-largest buyer of Russian oil exports to the EU.[274]

The new Energy Policy of Poland until 2040 (EPP2040) would reduce the share of coal and lignite in electricity generation by 25% from 2017 to 2030. The plan involves deploying new nuclear plants, increasing energy efficiency, and decarbonising the Polish transport system in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prioritise long-term energy security.[272][275]

Science and technology

Over the course of history, the Polish people have made considerable contributions in the fields of science, technology and mathematics.[277] Perhaps the most renowned Pole to support this theory was Nicolaus Copernicus (Mikołaj Kopernik), who triggered the Copernican Revolution by placing the Sun rather than the Earth at the center of the universe.[278] He also derived a quantity theory of money, which made him a pioneer of economics. Copernicus' achievements and discoveries are considered the basis of Polish culture and cultural identity.[279] Poland was ranked 41st in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[280]

Poland's tertiary education institutions; traditional

In the first half of the 20th century, Poland was a flourishing centre of mathematics. Outstanding Polish mathematicians formed the

Demographics

Poland has a population of approximately 38.2 million as of 2021, and is the

Around 60% of the country's population lives in urban areas or major cities and 40% in rural zones.

In the

| Rank | Name

|

Voivodeship | Pop. | Rank | Name

|

Voivodeship | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Warsaw  Kraków |

1 | Warsaw | Masovian | 1,860,281 | 11 | Katowice | Silesian | 285,711 |  Wrocław  Łódź |

| 2 | Kraków | Lesser Poland | 800,653 | 12 | Gdynia | Pomeranian | 245,222 | ||

| 3 | Wrocław | Lower Silesian | 672,929 | 13 | Częstochowa | Silesian | 213,107 | ||

| 4 | Łódź | Łódź | 670,642 | 14 | Radom | Masovian | 201,601 | ||

| 5 | Poznań | Greater Poland | 546,859 | 15 | Toruń | Kuyavian-Pomeranian |

198,273 | ||

| 6 | Gdańsk | Pomeranian | 486,022 | 16 | Rzeszów | Subcarpathian | 195,871 | ||

| 7 | Szczecin | West Pomeranian | 396,168 | 17 | Sosnowiec | Silesian | 193,660 | ||

| 8 | Bydgoszcz | Kuyavian-Pomeranian |

337,666 | 18 | Kielce | Świętokrzyskie | 186,894 | ||

| 9 | Lublin | Lublin | 334,681 | 19 | Gliwice | Silesian | 174,016 | ||

| 10 | Białystok | Podlaskie | 294,242 | 20 | Olsztyn | Warmian-Masurian |

170,225 | ||

Languages

Religion

According to the 2021 census, 71.3% of all Polish citizens adhere to the

Poland is one of the most religious countries in Europe, where Roman Catholicism remains a part of national identity and Polish-born Pope John Paul II is widely revered.[307][308] In 2015, 61.6% of respondents outlined that religion is of high or very high importance.[309] However, church attendance has greatly decreased in recent years; only 28% of Catholics attended mass weekly in 2021, down from around half in 2000.[310] According to The Wall Street Journal, "Of [the] more than 100 countries studied by the Pew Research Center in 2018, Poland was secularizing the fastest, as measured by the disparity between the religiosity of young people and their elders."[307]

Freedom of religion in Poland is guaranteed by the Constitution, and Poland's

Contemporary religious minorities include

Pilgrimages to the Jasna Góra Monastery, a shrine dedicated to the Black Madonna, take place annually.[315]

Health

Medical service providers and

According to the

Education

The Jagiellonian University founded in 1364 by Casimir III in Kraków was the first institution of higher learning established in Poland, and is one of the oldest universities still in continuous operation.[323] Poland's Commission of National Education (Komisja Edukacji Narodowej), established in 1773, was the world's first state ministry of education.[324][325]

The framework for primary, secondary and higher tertiary education are established by the Ministry of Education and Science. Kindergarten attendance is optional for children aged between three and five, with one year being compulsory for six-year-olds.[326][327] Primary education traditionally begins at the age of seven, although children aged six can attend at the request of their parents or guardians.[327] Elementary school spans eight grades and secondary schooling is dependent on student preference – a four-year high school (liceum), a five-year technical school (technikum) or various vocational studies (szkoła branżowa) can be pursued by each individual pupil.[327] A liceum or technikum is concluded with a maturity exit exam (matura), which must be passed in order to apply for a university or other institutions of higher learning.[328]

In Poland, there are over 500 university-level institutions,

Culture

The culture of Poland is closely connected with its intricate 1,000-year

Holidays and traditions

There are 13 government-approved annual public holidays – New Year on 1 January,

Particular traditions and superstitious customs observed in Poland are not found elsewhere in Europe. Though Christmas Eve (

A widely-popular

Music

Artists from Poland, including famous musicians such as

The origins of Polish music can be traced to the 13th century; manuscripts have been found in

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Polish baroque composers wrote liturgical music and secular compositions such as concertos and sonatas for voices or instruments. At the end of the 18th century, Polish classical music evolved into national forms like the polonaise. Wojciech Bogusławski is accredited with composing the first Polish national opera, titled Krakowiacy i Górale, which premiered in 1794.[349]

Poland today has an active music scene, with the jazz and metal genres being particularly popular among the contemporary populace. Polish jazz musicians such as

Art

Art in Poland has invariably reflected

Internationally renowned Polish artists include

Notable art academies in Poland include the

Architecture

The

The earliest architectonic trend was

Primary building materials comprising

Literature

The

The poets

Contemporary Polish literature is versatile, with its fantasy genre having been particularly praised.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Poland is eclectic and shares similarities with other regional cuisines. Among the staple or regional dishes are

Traditional dishes are hearty and abundant in pork, potatoes, eggs, cream, mushrooms, regional herbs, and sauce.

Traditional alcoholic beverages include honey mead, widespread since the 13th century, beer, wine and vodka.[393] The world's first written mention of vodka originates from Poland.[394] The most popular alcoholic drinks at present are beer and wine which took over from vodka more popular in the years 1980–1998.[395] Grodziskie, sometimes referred to as "Polish Champagne", is an example of a historical beer style from Poland.[396] Tea remains common in Polish society since the 19th century, whilst coffee is drunk widely since the 18th century.[397]

Fashion and design

Several Polish designers and stylists left a legacy of beauty inventions and cosmetics; including

Historically, fashion has been an important aspect of Poland's national consciousness or

Cinema

The

The

Media

According to the

Poland is a major European hub for video game developers and among the most successful companies are CD Projekt, Techland, The Farm 51, CI Games and People Can Fly.[411] Some of the popular video games developed in Poland include The Witcher trilogy and Cyberpunk 2077.[411] The Polish city of Katowice also hosts Intel Extreme Masters, one of the biggest esports events in the world.[411]

Sports

As of August 2023, the

Poland has made a distinctive mark

In the 21st century, the country has seen a growth of popularity of tennis and produced a number of successful tennis players including World No. 1

Poles made significant achievements in mountaineering, in particular, in the Himalayas and the winter ascending of the eight-thousanders. Polish mountains are one of the tourist attractions of the country. Hiking, climbing, skiing and mountain biking and attract numerous tourists every year from all over the world.[262] Water sports are the most popular summer recreation activities, with ample locations for fishing, canoeing, kayaking, sailing and windsurfing especially in the northern regions of the country.[422]

See also

Notes

- ^ "The dukes (dux) were originally the commanders of an armed retinue (drużyna) with which they broke the authority of the chieftains of the clans, thus transforming the original tribal organization into a territorial unit."[4]

- ^ "Mieszko accepted Roman Catholicism via Bohemia in 966. A missionary bishopric directly dependent on the papacy was established in Poznań. This was the true beginning of Polish history, for Christianity was a carrier of Western civilization with which Poland was henceforth associated."[5]

- ^ Polish: Polska [ˈpɔlska] ⓘ

- ^ Polish: Rzeczpospolita Polska [ʐɛt͡ʂpɔsˈpɔlita ˈpɔlska] ⓘ

- ^ Poland borders the Kaliningrad Oblast, an exclave of Russia.

References

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Poland, Article 27.

- ^ ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6. Archived(PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Final results of the National Population and Housing Census 2021". Statistics Poland.

- ^ "Poland". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "Poland". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "The Act of December 29, 1989 amending the Constitution of the Polish People's Republic". Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020. (in Polish)

- ^ GUS. "Powierzchnia i ludność w przekroju terytorialnym w 2023 roku". Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Poland country profile". BBC News. 12 November 2023. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Statistical Bulletin No 11/2022". Statistics Poland. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Poland)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024". United Nations Development Programme. 19 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ GUS. "Powierzchnia i ludność w przekroju terytorialnym w 2023 roku". Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4758-5626-2. Archivedfrom the original on 7 February 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 0-521-55109-9. Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-7063-411-7. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-190563-6. Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-28132-5. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-5017-5740-2.

- ISBN 978-963-386-418-0. Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-65746-64-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-3694-9. Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-913985-3-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-267-3653-7.

- from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ISBN 9789077922187.

- ISBN 978-0-19-885507-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-023198-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-136-63944-9. Archivedfrom the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-19-280126-5. Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Zdziebłowski, Szymon (9 May 2018). "Archaeologist: We have evidence of the presence of Roman legionaries in Poland". Science in Poland. Polish Ministry of Education and Science. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- PMID 23342138

- .

- ISBN 978-1-61530-991-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-5017-5740-2.

- ISBN 978-1-137-40281-3. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-963-9241-40-4

- ISBN 978-83-61033-36-3. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-8-323-13886-0.

- ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9.

- from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-85483-46-5. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

... w wersji Anonima Minoryty mówi się znowu, iż w Polsce "paliły się kościoły i klasztory", co koresponduje w przekazaną przez Anonima Galla wiadomością o zniszczeniu kościołów katedralnych w Gnieźnie...

- ISBN 978-83-909852-1-3. Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ]

- ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-7212-307-7. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-04-04985-7. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-11-11171-4. Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-88033-009-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-88032-27-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-922944-3-6. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-86516-245-7.

- ISBN 978-1-61530-991-7.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

At the same time, when most of Europe was decimated by the Black Death, Poland developed quickly and reached the levels of the wealthiest countries of the West in its economy and culture.

- ISBN 978-1-136-59313-0.

- ISBN 978-1-136-63944-9.

- ^ Magill 2012, p. 64

- ^ a b Davies 2001, p. 256

- ISBN 978-0-88033-206-4.

- ISBN 978-3-7489-0113-6. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1

- ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7.

By 1490 the Jagiellons controlled Poland–Lithuania, Bohemia, and Hungary, but not the Empire.

- ISBN 978-0-19-880020-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-317-88433-0. Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Graves 2014, pp. 101, 197

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85745-109-5.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-804-7. Archivedfrom the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-25220-0. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-300-21936-4. Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Parker 2017, p. 122

- ISBN 978-1-5312-6318-8. Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-916-7.

- ISBN 978-0-313-03456-5. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4766-0411-4. Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-337-75029-9. Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-902522-1-6. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-102000-1. Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Czapliński, Władysław (1976). Władysław IV i jego czasy [Władysław IV and His Times] (in Polish). Warsaw: PW "Wiedza Poweszechna". pp. 170, 217–218.

- ^ Scott 2015, p. 409

- ^ a b Scott 2015, pp. 409–413

- ^ Scott 2015, p. 411

- ^ Scott 2015, pp. 409–412, 666

- ^ Butterwick 2021, p. 88

- ^ Butterwick 2021, pp. 83–88

- ^ Butterwick 2021, pp. 89–91

- ^ Butterwick 2021, pp. 108–109

- ^ Butterwick 2021, pp. 108–116

- ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1, pp. 1–74

- ISBN 978-0-415-35491-2. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Butterwick 2021, p. 176

- ^ Polska Akademia Nauk (1973). Nauka polska. Polska Akademia Nauk. p. 151. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Butterwick 2021, p. 260

- ^ Butterwick 2021, p. 310

- ^ Józef Andrzej Gierowski – Historia Polski 1764–1864 (History of Poland 1764–1864), pp. 74–101

- ^ Bertholet, Auguste (2021). "Constant, Sismondi et la Pologne". Annales Benjamin Constant. 46: 65–85. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ISBN 90-5201-235-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4299-6607-8– via Google Books.

- ^ Gardner, Monica Mary (1942). "The Rising of Kościuszko (Chapter VII)". Kościuszko: A Biography. G. Allen & Unwin., ltd, 136 pages. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2014 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ISBN 978-0-87436-957-1. Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4438-1157-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-317-56810-0. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-90-5356-883-5. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 1-280-83513-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-319-97126-1. Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- Paris Peace Conference." Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World (2001), p. 208.

- ISBN 978-0-8444-0827-9.

- JSTOR 25779809.

- JSTOR 4202361.

- ^ Bitter glory: Poland and its fate, 1918 to 1939; p. 179

- JSTOR 45333442.

- ISBN 978-1-118-59808-5.

- ^ "Russian parliament condemns Stalin for Katyn massacre". BBC News. 26 November 2010

- ISBN 978-0-521-89796-9.

- ]

- ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 6 March 2011 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0-8156-2440-0. Retrieved 6 March 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ At the siege of Tobruk

- ^ including the capture of the monastery hill at the Battle of Monte Cassino

- ISBN 978-0-674-06814-8. Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-83-02-05500-3, p. 37

- ^ The Warsaw Rising, polandinexile.com

- ISBN 978-0-8032-1327-2.

- ISBN 978-1-101-90345-2.

- ^ Materski & Szarota (2009) Quote: Liczba Żydów i Polaków żydowskiego pochodzenia, obywateli II Rzeczypospolitej, zamordowanych przez Niemców sięga 2,7- 2,9 mln osób. Translation: The number of Jewish victims is estimated at 2,9 million. This was about 90% of the 3.3 million Jews living in prewar Poland. Source: IPN.

- ^ "Poland: Historical Background during the Holocaust". Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Polish Victims". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz. "Poland World War II casualties (in thousands)". Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Materski & Szarota (2009) Quote: Łączne straty śmiertelne ludności polskiej pod okupacją niemiecką oblicza się obecnie na ok. 2 770 000. Translation: Current estimate is roughly 2,770,000 victims of German occupation. This was 11.3% of the 24.4 million ethnic Poles in prewar Poland.

- ^ "Documenting Numbers of Victims of the Holocaust and Nazi Persecution". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8. Archived from the original(PDF) on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

Oblicza się, że akcja "Inteligencja" pochłonęła ponad 100 tys. ofiar. Translation: It is estimated that Intelligenzaktion took the lives of 100,000 Poles.

- ^ Grzegorz Motyka, Od rzezi wołyńskiej do akcji "Wisła". Konflikt polsko-ukraiński 1943–1947. Kraków 2011, p. 447. See also: Book review by Tomasz Stańczyk: "Grzegorz Motyka oblicza, że w latach 1943–1947 z polskich rąk zginęło 11–15 tys. Ukraińców. Polskie straty to 76–106 tys. zamordowanych, w znakomitej większości podczas rzezi wołyńskiej i galicyjskiej."

- ^ "What were the Volhynian Massacres?". 1943 Wołyń Massacres Truth and Remembrance. Institute of National Remembrance. 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Materski & Szarota (2009)

- ^ Holocaust: Five Million Forgotten: Non-Jewish Victims of the Shoah. Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Remember.org.

- ^ "Polish experts lower nation's WWII death toll". Archived from the original on 18 August 2019.

- ^ Bureau odszkodowan wojennych (BOW), Statement on war losses and damages of Poland in 1939–1945. Warsaw 1947

- ISBN 978-1-5361-1035-7. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-83-61590-46-0. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "European Refugee Movements After World War Two". BBC – History.

- ^ "ARTICLE by Karol Nawrocki, Ph.D.: The soldiers of Polish freedom". Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- I saw Poland betrayed: An American Ambassador Reports to the American People. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1948.

- ^ "Warsaw Pact: Definition, History, and Significance". Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Polska. Historia". PWN Encyklopedia (in Polish). Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2005.

- ^ "Solidarity Movement– or the Beginning of the End of Communism". September 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- JSTOR 25779611.

- ^ Kowalik, Tadeusz (2011). From Solidarity to Sell-Out: The Restoration of Capitalism in Poland. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- .

- JSTOR 23615759.

- ^ Sieradzka, Monika (3 November 2019). "After 20 years in NATO, Poland still eager to please". DW News. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

Poland's NATO accession in 1999 was meant to provide protection from Russia.

- S2CID 153998856.

- JSTOR 43580712.

- ^ "Europe's border-free zone expands". BBC News. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Smith, Alex Duval (7 February 2016). "Will Poland ever uncover the truth about the plane crash that killed its president?". The Guardian. Warsaw. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Turkowski, Andrzej. "Ruling Civic Platform Wins Parliamentary Elections in Poland". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Lynch, Suzanne. "Donald Tusk named next president of European Council". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "Poland elections: Conservatives secure decisive win". BBC News. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Poland's populist Law and Justice party win second term in power". The Guardian. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Rule of Law: European Commission acts to defend judicial independence in Poland". European Commission. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ "Poland's Duda narrowly beats Trzaskowski in presidential vote". BBC News. 13 July 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation". data.unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ "Donald Tusk elected as Polish prime minister". 11 December 2023. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Cechy krajobrazów Polski – Notatki geografia". Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- JSTOR 40869887.

- ISBN 978-3-319-16005-4.

- ISBN 978-3-319-71788-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-8926-4.

- ^ "Najwyższe szczyty w Tatrach Polskich i Słowackich". www.polskie-gory.pl. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Siwicki, Michał (2020). "Nowe ustalenia dotyczące wysokości szczytów w Tatrach". geoforum.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- S2CID 150809158.

- ISBN 978-1-61480-877-0. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

Insert: Poland is home to 9,300 lakes. Finland is the only European nation with a higher density of lakes than Poland.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-030-12123-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-822526-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b Zbigniew Ustrunul; Agnieszka Wypych; Ewa Jakusik; Dawid Biernacik; Danuta Czekierda; Anna Chodubska (2020). Climate of Poland (PDF) (Report). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management – National Research Institute (IMGW). p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Forest area (% of land area) – Poland". World Bank. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ISBN 978-83-65659-23-1. Archived(PDF) from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ISBN 978-3-030-83225-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Aniskiewicz, Alena (2016). "That's Polish: Exploring the History of Poland's National Emblems". culture.pl. Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

"A white eagle [...], the profile of a shaggy bison in a field of grass. These are emblems of Poland". "Nation's (somewhat disputed) national flower – the corn poppy".

- doi:10.1017/S1014233900004582. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-521-76061-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-686-6. Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-030-05960-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-94-035-0950-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (n.d.). "Civil Service; Basic information about Poland". www.gov.pl. Government of the Republic of Poland. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-94-035-2973-8. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-8223-173-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-315-68011-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-5099-1394-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- OCLC 1046634087.

- ^ ISBN 978-94-035-1324-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-94-035-3300-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Liczba jednostek podziału terytorialnego kraju". TERYT (in Polish). Statistics Poland (Główny Urząd Statystyczny GUS). 2022. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-030-61537-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b Government of Poland (2021). "Powierzchnia i ludność w przekroju terytorialnym w 2021 roku" (in Polish). Statistics Poland (Główny Urząd Statystyczny). Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-94-035-2961-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Sejm of the Republic of Poland. "Dziennik Ustaw nr 78: The Constitution of the Republic of Poland". sejm.gov.pl. National Assembly (Zgromadzenie Narodowe). Archived from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-94-035-2961-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-306-07095-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Nations, United (2020). "Human Development Indicators – Poland". Human Development Reports. United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Victims of intentional homicide 1990–2018 – Poland". Data UNODC. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-5381-4279-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7– via Internet Archive.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7.

- ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-84542-025-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- S2CID 154796013.

- ISBN 978-0-8157-3281-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Poland in the EU". Website of the Republic of Poland. Government of Poland. 2022. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-138-09795-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8122-2120-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-472-12879-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-643-91102-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-429-46866-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-83-7151-494-4. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-000-61972-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Onoszko, Maciej (20 August 2022). "Poland Will Double Military Spending as War in Ukraine Rages". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Popescu, Ana-Roxana (2022). "Poland to increase defence spending to 3% of GDP from 2023". Janes. Montagu Private Equity. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Lepiarz, Jacek (27 August 2022). "Europa Środkowa i Wschodnia nie kupuje niemieckiej broni". MSN. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ L., Wojciech (29 March 2022). "Quick and Bold: Poland's Plan To Modernize its Army". Overt Defense. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Government of Poland (2019). Eksport uzbrojenia i sprzętu wojskowego Polski (PDF) (Report). Warszawa (Warsaw): Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych MSZ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs). p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Day, Matthew (5 August 2008). "Poland ends army conscription". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ISBN 978-3-030-30697-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b Narodowego, Biuro Bezpieczeństwa. "Potencjał ochronny". Biuro Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Rybak, Marcin (6 December 2018). "Klient kontra ochrona sklepu. Czy mogą nas zatrzymać, przeszukać, legitymować?". Gazeta Wrocławska. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Rozdział 3 – Uprawnienia i obowiązki strażników – Straże gminne. – Dz.U.2019.1795 t.j." Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Policja o zwierzchnictwie nad Strażą Miejską w powiecie dzierżoniowskim". doba.pl. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Agencja Wywiadu". aw.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Antykorupcyjne, Centralne Biuro. "Aktualności". Centralne Biuro Antykorupcyjne. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Internet, J. S. K. "Status prawny". Centralne Biuro Śledcze Policji. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Projekt ustawy o krajowym systemie ratowniczym". orka.sejm.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Ustawa z dnia 25 lipca 2001 r. o Państwowym Ratownictwie Medycznym". isap.sejm.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "GDP growth (annual %) – Poland | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Inflation, consumer prices (annual %) – Poland | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (modeled ILO estimate) – Poland | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Lowest unemployment in the EU. Poland on the podium – Ministry of Family and Social Policy – Gov.pl website". Ministry of Family and Social Policy. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Poland National Debt 2020". countryeconomy.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Poland promoted to developed market status by FTSE Russell". Emerging Europe. September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Pracujący w rolnictwie, przemyśle i usługach | RynekPracy.org" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Polish economy seen as stable and competitive". Warsaw Business Journal. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Dorota Ciesielska-Maciągowska (5 April 2016). "Hundreds of foreign companies taken over by Polish firms over the last decade". Central European Financial Observer. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Thomas White International (September 2011), Prominent Banks in Poland. Emerging Market Spotlight. Banking Sector in Poland (Internet Archive). Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Worldbank.org, Global Financial Development Report 2014. Archived 7 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine Appendix B. Key Aspects of Financial Inclusion (PDF file, direct download). Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus. "The Global Competitiveness Report 2010–2011" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 27 (41/516). Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Exports of goods and services (BoP, current US$) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Ivana Kottasová (30 July 2019). "Brain drain claimed 1.7 million youths. So this country is scrapping its income tax". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Travel And Tourism in Poland". www.euromonitor.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ISBN 978-83-88679-84-1.

- ^ Press Release (5 November 2012). "International tourism strong despite uncertain economy". World Tourism Organization UNWTO. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "History of the Mine". www.wieliczka-saltmine.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ a b "UNTWO World Tourism Barometer, Vol.5 No.2" (PDF). www.tourismroi.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-74059-522-3.

- ISBN 978-1-78578-458-3.

- ^ "PAIH | Transport". www.paih.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad". www.gddkia.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Linie kolejowe w Polsce". utk.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-030-82095-4. Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-031-06108-0. Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-003-09207-0. Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-030-14519-4. Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ a b International Energy Agency (20 May 2022). "Poland – Countries & Regions". Paris: IEA. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Poland. Summary of Coal Industry" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ International Energy Agency (13 April 2022). "Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security". Paris: IEA. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Ministry of Climate and Environment (2 February 2021). "Energy Policy of Poland until 2040 (EPP2040)". Ministry of Climate and Environment of Poland. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7503-0224-1– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-83-7271-768-9. Archived from the originalon 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Nicolaus Copernicus Biography: Facts & Discoveries". Space.com. 20 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-58736-291-0.

- from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- S2CID 199470591. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020 – via content.sciendo.com.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link - ^ Statistics Poland (2021). Preliminary results of the National Population and Housing Census 2021. Główny Urząd Statystyczny GUS. p. 1. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Statistics Poland (2021). Area and population in the territorial profile (in English and Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny GUS. p. 20. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Fertility rate, total (births per woman) – Poland". World Bank. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Median age". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Urban population (% of the population) – Poland". World Bank. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "Distribution of population by degree of urbanisation, dwelling type and income group – EU-SILC survey". European Statistical Office "Eurostat". European Commission. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Funkcje Metropolitalne Pięciu Stolic Województw Wschodnich Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Markowski

- ^ World Urbanization Prospects Archived 16 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine – United Nations – Department of Economic and Social Affairs / Population Division, The 2003 Revision (data of 2000)

- ^ Eurostat, Urban Audit database Archived 6 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on 12 March 2009. Data for 2004.

- ^ Cox, Wendell (2013). "Major Metropolitan Areas in Europe". New Geography. Joel Kotkin and Praxis Strategy Group. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- European Spatial Planning Observation Network, Study on Urban Functions (Project 1.4.3) Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Final Report, Chapter 3, (ESPON, 2007)

- S2CID 134111630.

- ^ Statistics Poland (n.d.). The Concept of the International Migration. Statistics System in Poland (PDF). Główny Urząd Statystyczny GUS. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Filling Poland's labour gap". Poland Today. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Departament Rynku Pracy MRPiPS (2021). "Zezwolenia na pracę cudzoziemców". psz.praca.gov.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Informacja o wynikach Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2021 na poziomie województw, powiatów i gmin". stat.gov.pl. 2022. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ "GUS – Bank Danych Lokalnych". bdl.stat.gov.pl. 2022. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-90-272-0170-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Treaty 157). Council of Europe. 1 February 1995. Retrieved 15 September 2021. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ISBN 978-1-137-56914-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-138-78788-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Act of 6 January 2005 on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages" (PDF). GUGiK.gov.pl. Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii (Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-3-030-41575-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Obwieszczenie Marszałka Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 5 kwietnia 2017 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia jednolitego tekstu ustawy o mniejszościach narodowych i etnicznych oraz o języku regionalnym". isap.sejm.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-11-067299-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Infographic – Religiousness of Polish inhabitants". Statistics Poland (Główny Urząd Statystyczny). 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Coppen, Luke (18 January 2023). "How steep is Poland's drop in Mass attendance?". The Pillar. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-137-43751-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8122-1567-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-11-083868-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland, 2008" (PDF). Central Statistical Office. 28 July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-7112-4508-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Niecierpliwi". www.termedia.pl. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Prywatnie leczy się już ponad połowa Polaków". 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Poland Guide: The Polish health care system, An introduction: Poland's health care is based on a general". Justlanded.com. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Nations, United (2020). "Poland – Human Development Indicators". Human Development Reports. United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Poland: Country Health Profile 2019 | READ online". OECD iLibrary. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Imports of Drugs and Medicines by Country". World's Top Exports. 4 April 2020. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "History – Jagiellonian University – Jagiellonian University". en.uj.edu.pl. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ISBN 978-90-420-0933-2. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- OCLC 660185612.

- ^ "Zmiany w wychowaniu przedszkolnym - Informacje - Wychowanie przedszkolne w Polsce - wiek, obowiązek, miejsce, opłaty - dlaprzedszkolaka.info". www.dlaprzedszkolaka.info. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "Ustawa z dnia 14 grudnia 2016 r." (PDF). isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "MATURA 2020 | wymagania na STUDIA | jak wygląda | terminy". otouczelnie.pl.

- ^ Central Statistical Office: Studenci szkół wyższych (łącznie z cudzoziemcami) na dzień 30 XI 2008. Number of students at Poland's institutions of higher education, as of 30 November 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2012. Archived at Archive.org on 28 October 2008. (in Polish)

- ^ "Study in Poland". studies.info. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ "Ranking Uczelni Akademickich – Ranking Szkół Wyższych PERSPEKTYWY 2019". ranking.perspektywy.pl.

- ^ OECD (2009). "The impact of the 1999 education reform in Poland". Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) Results from PISA 2018" (PDF). OECD. 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-7818-0200-0

- ^ "Biało-Czerwoni – definicja, synonimy, przykłady użycia". sjp.pwn.pl.

- JSTOR 3032734.

- ^ "Zabytki nieruchome". www.nid.pl. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Album "100 pomników historii"". www.nid.pl. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage. "Poland". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Obwieszczenie Marszałka Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 19 grudnia 2014 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia jednolitego tekstu ustawy o dniach wolnych od pracy". isap.sejm.gov.pl.

- ^ "Opłatek i pierwsza gwiazdka czyli wigilijne tradycje". wegorzewo.wm.pl.

- ^ "Why Do Poles Leave One Chair Empty on Christmas Eve?". Culture.pl.

- ^ "turoń – słownik języka polskiego i poradnia językowa – Dobry słownik". DobrySłownik.pl.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-030-38117-2– via Google Books.

- ^ "Śmigus-Dyngus: Poland's National Water Fight Day". Culture.pl.

- ^ "Summer in Warsaw | Things You Can Do Only in Summer". 21 October 2018.

- ISBN 978-83-65972-34-7.

- ^ "The Music Courts of the Polish Vasas" (PDF). www.semper.pl. p. 244. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-7429-1.

- ^ "Pol'and'Rock: Poland's biggest music fest kicks off". polskieradio.pl. 4 August 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-4062-2826-7.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, 2002–2007, An Overview of Polish Culture Archived 2 April 2009 at the Wayback MachineAccess date 13 December 2007.

- ^ "Lady with an Ermine – by Leonardo Da Vinci". LeonardoDaVinci.net.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33811-3. Retrieved 31 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sarzyński, Piotr (12 February 2013). "Ranking polskich galerii ze współczesną sztuką". www.polityka.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-88-6655-489-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4875-2331-2.

- ISBN 83-223-2392-1.

- ISBN 978-83-85001-89-8.

- ISBN 978-3-03911-128-2.

- ISBN 978-83-88080-42-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4438-3295-3.

- ISBN 978-83-64091-55-1.

- ISBN 978-83-85739-14-2.

- ^ Many designs imitated the arcaded courtyard and arched loggias of the Wawel palace. Michael J. Mikoś. "Renaissance Cultural Background". www.staropolska.pl. p. 9. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- JSTOR 40870954.

- ISBN 978-83-7242-153-1.

- OCLC 636790894.

- ISBN 978-1-000-37738-5.

- ISBN 978-88-492-9191-9.

- ISBN 978-1-56518-142-7– via Google Books.

- ^ Koca, B. (2006). "Polish Literature – The Middle Ages (Religious writings)" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- ^ www.ideo.pl, Ideo Sp. z o.o. –. "The manuscript with the first ever sentence in Polish has be [sic] digitalized – News – Science & Scholarship in Poland". scienceinpoland.pap.pl. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "The first sentence in Polish in the UNESCO register". #Poland. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Polish Libraries – Wiesław Wydra: The Oldest Extant Prose Text in the Polish language. The Phenomenon of the Holy Cross Sermons". polishlibraries.pl. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-521-02438-9.

- ^ "Dwujęzyczność w twórczości Jana Kochanowskiego". fp.amu.edu.pl.

- ISBN 978-0-520-23357-7. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-118-77907-1. Retrieved 24 May 2017 – via Google Books.

- ]

- ^ "The Joseph Conrad Society (UK) Official Website". josephconradsociety.org. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "The Joseph Conrad Society of America". josephconrad.org. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-5381-3010-0.

- ^ "O Wiedźminie i Wiedźmince". Rynek książki. 19 July 2023.

- ^ "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Literature". Nobelprize.org. 5 October 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Adam Gopnik (5 June 2007). "Szymborska's 'View': Small Truths Sharply Etched". npr.org. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Tokarczuk and Handke win Nobel Literature Prizes". BBC News. 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Always home-made, tomato soup is one of the first things a Polish cook learns to prepare." [in:] Marc E. Heine. Poland. 1987

- ISBN 978-0-7818-0994-8– via Google Books.

- ^ Amanda Fiegl (17 December 2008). "A Brief History of the Bagel". smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-456-8.

- ISBN 978-1-63121-624-4.

- ^ "gorzała – Słownik języka polskiego PWN". sjp.pwn.pl.

- ^ "History of vodka production, at the official page of Polish Spirit Industry Association (KRPS), 2007". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ "EJPAU 2004. Kowalczuk I. CONDITIONS OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES CONSUMPTION AMONG POLISH CONSUMERS". www.ejpau.media.pl.

- ^ Jim Hughes (4 February 2013). "Forgotten Beer Styles: Grodziskie". badassdigest.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-7818-1124-8. Retrieved 31 March 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Maks Faktorowicz: Polak, który stworzył kosmetyczne imperium" [Maks Faktorowicz: A Pole who created a cosmetic empire]. Interia Kobieta (in Polish). 7 February 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Maksymilian Faktorowicz – człowiek, który dał nam sztuczne rzęsy" [Maksymilian Faktorowicz – a man who gave us false eyelashes]. Polskie Radio (in Polish). Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Stella Rose Saint Clair (12 February 2014). "Makeup Masters: The History of Max Factor". Beautylish. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Norbert Ziętal (13 July 2013). "Przemyski Inglot ma już 400 sklepów na świecie" [Przemysl Inglot already has 400 stores in the world]. Strefa Biznesu (in Polish).

- ^ Butler, Sarah (2 September 2016). "Reserved! Polish fashion chain moves into BHS flagship store". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ OCLC 607873644.

- ^ "The Wrightsman Collection. Vols. 1 and 2, Furniture, Gilt Bronze and Mounted Porcelain, Carpets". Metropolitan Museum of Art – via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4766-0803-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-322-88919-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4408-4466-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8325-8614-0.

- ^ Cabrera, Isabel (2020). "World Reading Habits in 2020 [Infographic]". geediting.com. Global English Editing. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-118-78404-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-83-7633-451-6.

- ^ "FIFA World Cup Statistics-Poland". FIFA. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "FIFA Statistics – Poland". Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Poland hosts Euro 2012!". warsaw-life.com. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "FIVB Senior World Ranking – Men". Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championship Poland 2014". Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Finals". Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ISBN 978-83-7552-707-0.

- ^ "Speedway World Cup: Poland win 2010 Speedway World Cup". worldspeedway.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Blanka Konopka (10 June 2022). "Tennis fever hits Poland as clubs across the country report surge in interest". thefirstnews.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "Poland wins Hopman Cup as Agnieszka Radwanska and Jerzy Janowicz combine to beat Serena Williams and John Isner in Perth". abc.net.au. 10 January 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Summer Sports in Poland at Poland For Visitors Online. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

Works cited

- Materski, Wojciech; Andrzej Krzysztof Kunert. Archived from the originalon 31 March 2012.

External links

- Poland.gov.en – Polish national portal. Archived 3 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- Poland. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 32 (12th ed.). 1922.

- Poland at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of Poland

Wikimedia Atlas of Poland Geographic data related to Poland at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Poland at OpenStreetMap