Fluvoxamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Luvox, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695004 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 53% (90% confidence interval: 44–62%)[3] |

| Protein binding | 77–80%[3][4] |

| Metabolism | Liver (primarily O-demethylation) Major: CYP1A2 Minor: CYP3A4 Minor: CYP2C19[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 12–13 hours (single dose), 22 hours (repeated dosing)[3] |

| Excretion | Kidney (98%; 94% as metabolites, 4% as unchanged drug)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

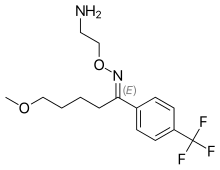

Fluvoxamine, sold under the brand name Luvox among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class.[6] It is primarily used to treat major depressive disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[7] but is also used to treat anxiety disorders[8] such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[9][10][11]

Fluvoxamine's side-effect profile is very similar to other SSRIs:

Although the many drug-drug interactions of fluvoxamine can be problematic (and may temper enthusiasm for its prescribing, advocation and usage to some), its tolerance-profile itself is actually superior in some respects to other SSRIs (particularly with respect to cardiovascular complications), despite its age.[13] Compared to escitalopram and sertraline, indeed, fluvoxamine's gastrointestinal profile may be less intense,[14] often being limited to nausea.[15] Mosapride has demonstrated efficacy in treating fluvoxamine-induced nausea.[16] It is also advised practice to divide total daily doses of fluvoxamine greater than 100 milligrams, with the higher fraction being taken at bedtime (e.g., 50 mg at the beginning of the waking day and 200 mg at bedtime). In any case, high starting daily doses of fluvoxamine rather than the recommended gradual titration (starting at 50 milligrams and gradually titrating, up to 300 if necessary) may predispose to nauseous discomfort.[17]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[18]

Medical uses

In many countries (e.g., Australia,

There is evidence that fluvoxamine is effective for

Fluvoxamine is also effective for treating a range of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and separation anxiety disorder.[34][35][36]

The drug works long-term, and retains its therapeutic efficacy for at least one year.[37] It has also been found to possess some analgesic properties in line with other SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants.[38][39][40]

The average therapeutic dose for fluvoxamine is 100 to 300 mg/day, with 300 mg being the upper daily limit normally recommended.

Adverse effects

Fluvoxamine's side-effect profile is very similar to other SSRIs, with

Common

Common side effects occurring with 1–10% incidence:

- Abdominal pain

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Asthenia(weakness)

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Dizziness

- Dyspepsia(indigestion)

- Headache

- Hyperhidrosis (excess sweating)

- Insomnia

- Loss of appetite

- Malaise

- Nausea

- Nervousness

- Palpitations

- Restlessness

- Sexual dysfunction (including delayed ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, etc.)

- Somnolence (drowsiness)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Tremor

- Vomiting

- Weight loss

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- Yawning

Uncommon

Uncommon side effects occurring with 0.1–1% incidence:

- Arthralgia

- Confusional state

- Cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions (e.g. oedema [buildup of fluid in the tissues], rash, pruritus)

- Extrapyramidal side effects (e.g. dystonia, parkinsonism, tremor, etc.)

- Hallucination

- Orthostatic hypotension

Rare

Rare side effecs occurring with 0.01–0.1% incidence:

- Abnormal hepatic (liver) function

- Galactorrhoea (expulsion of breast milk unrelated to pregnancy or breastfeeding)

- Mania

- Photosensitivity (being abnormally sensitive to light)

- Seizures

Unknown frequency

- Akathisia – a sense of inner restlessness that presents itself with the inability to stay still

- Bed-wetting

- Bone fractures

- Dysgeusia

- Ecchymoses

- Glaucoma

- Haemorrhage

- Hyperprolactinaemia (elevated plasma prolactin levels leading to galactorrhoea, amenorrhoea [cessation of menstrual cycles], etc.)

- Hyponatraemia

- Mydriasis

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome – practically identical presentation to serotonin syndrome except with a more prolonged onset

- Paraesthesia

- Serotonin syndrome – a potentially fatal condition characterised by abrupt onset muscle rigidity, hyperthermia (elevated body temperature), rhabdomyolysis, mental status changes (e.g. coma, hallucinations, agitation), etc.

- Suicidal ideation and behaviour

- Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

- Urinary incontinence

- Urinary retention

- Violence towards others[47]

- Weight changes

- Withdrawal symptoms

Interactions

Fluvoxamine inhibits the following cytochrome P450 enzymes:[48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][excessive citations]

- CYP1A2 (strongly) which metabolizes agomelatine, amitriptyline, caffeine, clomipramine, clozapine, duloxetine, haloperidol, imipramine, phenacetin, tacrine, tamoxifen, theophylline, olanzapine, etc.

- CYP3A4 (moderately) which metabolizes alprazolam, aripiprazole, clozapine, haloperidol, quetiapine, pimozide, ziprasidone, etc.[57]

- CYP2D6 (weakly) which metabolizes aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, clozapine, codeine, fluoxetine, haloperidol, olanzapine, oxycodone, paroxetine, perphenazine, pethidine, risperidone, sertraline, thioridazine, zuclopenthixol, etc.[58]

- sulfonylureas, etc.

- CYP2C19 (strongly) which metabolizes clonazepam, diazepam, phenytoin, etc.

- CYP2B6 (weakly) which metabolizes bupropion, cyclophosphamide, sertraline, tamoxifen, valproate, etc.

By so doing, fluvoxamine can increase serum concentration of the substrates of these enzymes.[48]

Fluvoxamine may also elevate plasma levels of olanzapine by approximately two times.[59] Combined olanzapine and fluvoxamine, which may cause increased sedation,[60] should be used cautiously and controlled clinically and by therapeutic drug monitoring to avoid olanzapine induced adverse effects and/or intoxication.[61][62]

The plasma levels of oxidatively metabolized benzodiazepines (e.g., triazolam, midazolam, alprazolam and diazepam) are likely to be increased when co-administered with fluvoxamine. However, the clearance of benzodiazepines metabolized by glucuronidation (e.g., lorazepam; oxazepam, which is coincidentally a metabolite of diazepam;[63] temazepam)[64][65] are not affected by fluvoxamine and may be safely taken alongside fluvoxamine should concurrent treatment with a benzodiazepine be necessary.[66] Additionally, it appears that benzodiazepines metabolized by nitro-reduction (clonazepam, nitrazepam) may also, in a somewhat similar vein, be unlikely to be affected by fluvoxamine.[67][68]

Using fluvoxamine and alprazolam together can increase alprazolam plasma concentrations.[69] If alprazolam is coadministered with fluvoxamine, the initial alprazolam dose should be reduced to the lowest effective dose.[70][71]

Fluvoxamine and ramelteon coadministration is not indicated.[72][73]

Fluvoxamine has been observed to increase serum concentrations of mirtazapine, which is mainly metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4, by three- to four-fold in humans.[74] Caution and adjustment of dosage as necessary are warranted when combining fluvoxamine and mirtazapine.[74]

Fluvoxamine seriously affects the pharmacokinetics of tizanidine and increases the intensity and duration of its effects. Because of the potentially hazardous consequences, the concomitant use of tizanidine with fluvoxamine, or other potent inhibitors of CYP1A2, should be avoided.[75]

When a beta-blocker is required, atenolol,[76] pindolol[77][78][79] and, possibly, metoprolol[80][81][57][82] may be safer choices than propranolol, as the latter's metabolism is seriously, potentially dangerously, inhibited by fluvoxamine.[83] Indeed, fluvoxamine may increase propranolol blood-levels by five-fold.[84]

Clomipramine increases fluvoxamine levels and, conversely-likewise, fluvoxamine increases clomipramine levels (thereby its serotoninergic potential) and inhibits its metabolism to its strongly-noradrenergic metabolite, norclomipramine.[85][86]

Pharmacology

| Site | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 2.5 |

| NET | 1,427 |

| 5-HT2C | 5,786 |

| α1-adrenergic | 1,288 |

| σ1 | 36 |

Fluvoxamine is a potent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with around 100-fold affinity for the serotonin transporter over the norepinephrine transporter.[49] It has negligible affinity for the dopamine transporter or any other site, with the sole exception of the σ1 receptor.[90][13] It behaves as a potent agonist at this receptor and has the highest affinity (36 nM) of any SSRI for doing so.[90] This may contribute to its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects and may also afford it some efficacy in treating the cognitive symptoms of depression.[91] Unlike some other SSRIs, fluvoxamine's metabolites are pharmacologically neutral.[92]

History

Fluvoxamine was developed by Kali-Duphar,

Research directions

While early studies have suggested potential benefits for fluvoxamine as an anti-inflammatory agent and a possible impact on reducing cytokine storms, further studies did not confirm this expected benefit on COVID-19 patients.[105][106] A cytokine storm refers to an excessive immune response characterized by a release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[107]

In May 2022, based on a review of available scientific evidence, the U.S.

A large double-blind randomized controlled trial called ACTIV-6, published in 2023 in JAMA, revealed that taking 200 mg of fluvoxamine every day for about two weeks was not significantly better than placebo at shortening the duration of mild or moderate COVID-19 symptoms.[110][medical citation needed]

There is tentative evidence that fluvoxamine may reduce the overall morbidity of COVID-19 and complications thereof.[111][112]

Environment

Fluvoxamine is a common finding in waters near human settlement.[113] Christensen et al. 2007 finds it is "very toxic to aquatic organisms" by European Union standards.[113]

References

- ^ Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Product Information Luvox". TGA eBusiness Services. Abbott Australasia Pty Ltd. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- S2CID 84636672.

- ^ "Luvox". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine Maleate Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ PMID 20140100.

- PMID 11323729.

- S2CID 265712201.

- PMID 18568110.

- S2CID 40412606.

- ^ Vezmar, S. et al., « Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of Fluvoxamine and Amitriptyline in Depression », J Pharmacol Sci, vol. 110, no 1, 2009, p. 98 – 104 (ISSN 1347-8648)

- ^ PMID 16620364.

- S2CID 231809760.

- PMID 18568110.

- S2CID 38761139.

- from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ "Luvox Tablets". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ "Summary of Full Prescribing Information: Fluvoxamine". Drug Registry of Russia (RLS) Drug Compendium (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Fluvoxamine Maleate tablet, coated prescribing information". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 14 December 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Luvox CR approved for OCD and SAD". MPR. 29 February 2008. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "2005 News Releases". Astellas Pharma. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "International Approvals: Ebixa, Depromel/Luvox, M-Vax". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine Product Insert" (PDF). Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- PMID 29048739.

- PMID 29995828.

- ^ Williams, T., McCaul, M., Schwarzer, G., Cipriani, A., Stein, D. J., & Ipser, J. (2020). Pharmacological treatments for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta neuropsychiatrica, 32(4), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2020.6

- ^ Davidson J. R. (2003). Pharmacotherapy of social phobia. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, (417), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.7.x

- ^ Tancer, M. E., & Uhde, T. W. (1997). Role of serotonin drugs in the treatment of social phobia. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 58 Suppl 5, 50–54.

- ^ Aarre T. F. (2003). Phenelzine efficacy in refractory social anxiety disorder: a case series. Nordic journal of psychiatry, 57(4), 313–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310002110

- from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- PMID 32982805.

- PMID 34002501.

- S2CID 195691900.

- PMID 12043315.

- S2CID 39278756.

- S2CID 8229797.

- ^ Seibell PJ, Hamblin RJ, Hollander E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Overview and standard treatment strategies. Psychiatric Annals. 2015 Jun 1;45(6):297-302.

- ^ Rivas-Vazquez, R.A. and Blais, M.A., 1997. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and atypical antidepressants: A review and update for psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28(6), p.526.

- ^ Middleton, R., Wheaton, M.G., Kayser, R. and Simpson, H.B., 2019. Treatment resistance in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Treatment resistance in psychiatry: risk factors, biology, and management, pp.165-177.

- ^ Figgitt, D.P. and McClellan, K.J., 2000. Fluvoxamine: an updated review of its use in the management of adults with anxiety disorders. Drugs, 60, pp.925-954.

- ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ^ "Faverin 100 mg film-coated tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Abbott Healthcare Products Limited. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Szalavitz M (7 January 2011). "Top Ten Legal Drugs Linked to Violence". Time. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60327-435-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- S2CID 31923953.

- PMID 9184622.

- S2CID 22297498.

- S2CID 23859992.

- PMID 17823102.

- ^ Waknine Y (13 April 2007). "Prescribers Warned of Tizanidine Drug Interactions". Medscape News. Medscape. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine (Oral Route) Precautions". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ PMID 11876575.

- ^ "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". FDA. 26 May 2021. Archived from the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- PMID 17214606.

- S2CID 43395897.

- S2CID 38073367.

- ^ "Movox". NPS MedicineWise. 23 November 2020. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- S2CID 4528255.

- ^ Raouf M (2016). Fudin J (ed.). "Benzodiazepine Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- S2CID 1389910.

- ^ "fluvoxamine maleate: PRODUCT MONOGRAPH" (PDF). 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Luvox Data Sheet" (PDF). Medsafe, New Zealand. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Faverin Tablets". NPS MedicineWise. July 2022. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- S2CID 32559753.

- ISBN 978-3-7091-1500-8. Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- S2CID 2161450.

- S2CID 8421997.

- PMID 23861638.

- ^ S2CID 44807359.

- S2CID 25781307.

- S2CID 22472247.

- S2CID 22692759.

- ^ Sluzewska A, Szczawinska K (May 1996). "The effects of pindolol addition to fluvoxamine and buspirone in chronic mild stress model of depression". Behavioural Pharmacology. 7: 105.

- S2CID 23946424.

- S2CID 28105445.

- PMID 8904628.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link - ^ Belpaire FM, Wijnant P, Tammerman A, Bogaert M, Rasmussen B, Brosen K (1997). "Inhibition of the oxidative metabolism of metoprolol by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in human liver microsomes". Fundamental and Clinical Pharmacology. 2 (11): 147.

- S2CID 71812133.

- S2CID 11592004.

- PMID 8666564.

- PMID 34777510.

- S2CID 728565.

- OCLC 320111564.

- PMID 28501470.

- ^ PMID 20021354.

- S2CID 26491662.

- PMID 1931931.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8155-1526-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- PMID 15995053.

- ^ "Brand Index―Fluvoxamine India". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- PMID 20238342.

- ^ "OCD Medication". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine Product Monograph" (PDF). 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Luvox Approved For Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Children and Teens". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- PMID 19300537.

- Human Metabolome Database, HMDB. 5.0.

- ^ "Solvay's Fluvoxamine maleate is first drug approved for the treatment of social anxiety disorder in Japan". Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-4293-5.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- S2CID 247978477.

- PMID 36532776.

- PMID 32592501.

- ^ "FDA declines to authorize common antidepressant as COVID treatment". Reuters. 16 May 2022. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Memorandum Explaining Basis for Declining Request for Emergency Use Authorization of Fluvoxamine Maleate (PDF) (Memorandum). Food and Drug Administration. 16 May 2022. 4975580. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Ingram I (17 November 2023). "Higher-Dose Fluvoxamine Fails for COVID Outpatients". MedPage Today. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- PMID 36103313.

- PMID 38516100.

- ^ a b

- • Chia MA, Lorenzi AS, Ameh I, Dauda S, Cordeiro-Araújo MK, Agee JT, et al. (May 2021). "Susceptibility of phytoplankton to the increasing presence of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the aquatic environment: A review". Aquatic Toxicology. 234. S2CID 6562531.

- • Chia MA, Lorenzi AS, Ameh I, Dauda S, Cordeiro-Araújo MK, Agee JT, et al. (May 2021). "Susceptibility of phytoplankton to the increasing presence of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the aquatic environment: A review". Aquatic Toxicology. 234.