Baeyer–Villiger oxidation

| Baeyer-Villiger oxidation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Named after | Adolf von Baeyer Victor Villiger | ||||||||

| Reaction type | Organic redox reaction | ||||||||

| Reaction | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Organic Chemistry Portal | baeyer-villiger-oxidation | ||||||||

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000031 | ||||||||

The Baeyer–Villiger oxidation is an

Reaction mechanism

In the first step of the

The products of the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation are believed to be controlled through both primary and secondary

The migratory ability is ranked tertiary > secondary > aryl > primary.

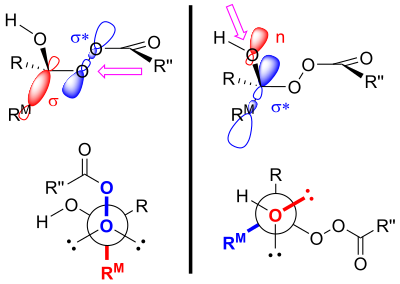

Another explanation uses stereoelectronic effects and steric arguments.

The migrating group in acyclic ketones, usually, is not 1° alkyl group. However, they may be persuaded to migrate in preference to the 2° or 3° groups by using CF3CO3H or BF3 + H2O2 as reagents.[12]

Historical background

In 1899, Adolf Baeyer and Victor Villiger first published a demonstration of the reaction that we now know as the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation.[13][14] They used peroxymonosulfuric acid to make the corresponding lactones from camphor, menthone, and tetrahydrocarvone.[14][15]

There were three suggested

In 1953, William von Eggers Doering and Edwin Dorfman elucidated the correct pathway for the reaction mechanism of the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation by using oxygen-18-labelling of benzophenone.[16] The three different mechanisms would each lead to a different distribution of labelled products. The Criegee intermediate would lead to a product only labelled on the carbonyl oxygen.[16] The product of the Wittig and Pieper intermediate is only labeled on the alkoxy group of the ester.[16] The Baeyer and Villiger intermediate leads to a 1:1 distribution of both of the above products.[16] The outcome of the labelling experiment supported the Criegee intermediate,[16] which is now the generally accepted pathway.[1]

Stereochemistry

The migration does not change the stereochemistry of the group that transfers, i.e.: it is stereoretentive.[18][19]

Reagents

Although many different peroxyacids are used for the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation, some of the more common

Limitations

The use of

Modifications

Catalytic Baeyer-Villiger oxidation

The use of hydrogen peroxide as an

Asymmetric Baeyer-Villiger oxidation

There have been attempts to use

Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases

In nature,

BVMOs are closely related to the flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs),[32] enzymes that also occur in the human body, functioning within the frontline metabolic detoxification system of the liver along the cytochrome P450 monooxygenases.[33] Human FMO5 was in fact shown to be able to catalyse Baeyer-Villiger reactions, indicating that the reaction may occur in the human body as well.[34]

BVMOs have been widely studied due to their potential as biocatalysts, that is, for an application in organic synthesis.[35] Considering the environmental concerns for most of the chemical catalysts, the use of enzymes is considered a greener alternative.[29] BVMOs in particular are interesting for application because they fulfil a range of criteria typically sought for in biocatalysis: besides their ability to catalyse a synthetically useful reaction, some natural homologs were found to have a very large substrate scope (i.e. their reactivity was not restricted to a single compound, as often assumed in enzyme catalysis),[36] they can be easily produced on a large scale, and because the three-dimensional structure of many BVMOs has been determined, enzyme engineering could be applied to produce variants with improved thermostability and/or reactivity.[37][38] Another advantage of using enzymes for the reaction is their frequently observed regio- and enantioselectivity, owed to the steric control of substrate orientation during catalysis within the enzyme's active site.[29][35]

Applications

Zoapatanol

Zoapatanol is a biologically active molecule that occurs naturally in the zeopatle plant, which has been used in Mexico to make a tea that can induce menstruation and labor.[39] In 1981, Vinayak Kane and Donald Doyle reported a synthesis of zoapatanol.[40][41] They used the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation to make a lactone that served as a crucial building block that ultimately led to the synthesis of zoapatanol.[40][41]

Steroids

In 2013, Alina Świzdor reported the transformation of the steroid dehydroepiandrosterone to anticancer agent testololactone by use of a Baeyer–Villiger oxidation induced by fungus that produces Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases.[42]

See also

- Dakin reaction

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-369483-6.

- ^ ISBN 0471264180.

- ^ ISBN 978-0387683546.

- ^ PMID 11027987.

- ^ a b c d Myers, Andrew G. "Chemistry 115 Handouts: Oxidation" (PDF). Harvard University.

- PMID 17367197.

- ^ PMID 15352787.

- ^ Li, Jie Jack; Corey, E. J., eds. (2007). Name Reactions of Functional Group Transformations. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-0-393-93149-5.

- ^ a b c d Evans, D. A. "Stereoelectronic Effects-2". Chemistry 206 (Fall 2006-2007).

- ISBN 978-81-7709-605-7.

- .

- ^ ISBN 0471264180.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ .

- .

- .

- S2CID 98508888.

- PMID 26267787.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-035930-4.

- ^ a b c Seymour, Craig. "Page 1 The Asymmetric Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation" (PDF). scs.illinois.edu.

- .

- PMID 11281784.

- .

- PMID 12240094.

- PMID 12561111.

- ^ PMID 21542563.

- PMID 11551214.

- PMID 22239272.

- PMID 16712999.

- PMID 17482904.

- PMID 26771671.

- ^ .

- PMID 30687578.

- PMID 31124128.

- PMID 30044629.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ .

- PMID 24213656.